Scene 1:

The Setting, Venice

While the opulence of the ornamentation in I Saw Othello’s Visage in His Mind evokes Venetian eighteenth-century style, White culture’s desire for luxury emerged in Renaissance Venice. The republic exploited luxury to help create its public image. Known as the “Myth of Venice,” its reputation was dependent upon its status as an independent maritime empire, devoted to the ideals of humanism, anti-tyranny, and a defender of liberty.[1] This led many politicians and scholars to refer to the state as “La Serenissima,” the most serene republic, as well as a “New Rome.”[2] This connection to Rome was no coincidence and was further perpetuated in the Venetian arts, which the republic acted as a leading patron as one can see from the Doge’s Palace [Fig. 7] and St. Mark’s Basilica [Fig. 8].[3] The republic even encouraged conspicuous consumption if it helped further the myth, such as through Venetian pageantry.[4] Pageantry became especially popular during the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War (1570-1573), which was the backdrop for Othello.[5] This connection reinforces Wilson’s references to Venetian opulence in his mirror’s style while also calling it into question. The mirror’s black glass makes clear that what is seen is not always what is true, thereby critiquing the republic’s façade of opulence. It was not until the eighteenth century that scholars began addressing the fallacy of Venice’s reputation and revealed that the “Myth of Venice” was just that—a “veneer of propaganda and mythology.”[6] Today, there is still debate about the republic’s image, and whether the Venetian past should be read in the larger socio-political discourse of the Renaissance altogether.[7]

Recent efforts in the humanities and in the arts, like Wilson’s I Saw Othello’s Visage in His Mind, want to unlink the Renaissance from Eurocentrism, the viewpoint that the Western world is the premier cultivator of civilization.[8] In other words, scholars want to challenge the idea that the values the Venetian republic stood for warranted the exploitation on which they were staked. Despite these efforts, it is evident that this crafted image of Renaissance Venice still has a grasp on public perception today. For example, in the preface for the 2003 Biennale, artistic director Francesco Bonami explained that his vision for the “Grand Show” needed to reflect “a multitude of worldviews… reduc[ing] the influence of imposed pre-packaged hegemonic views.”[9] It seems Bonami wanted to embrace a changing worldview that was not defined by past values which, in his mind, reflected “almost Christian attitude…as if attempting the moral and cultural conquest of the world.”[10] Thus the point of Bonami’s Biennale was to critique such viewpoints that disallowed diversity. For Wilson’s pavilion, he understood this as critiquing the Western perspective of Renaissance Venice. As he noted from his time spent in Venice, while Black people appear throughout the Venetian arts they largely were represented as stereotypes rather than realities.[11] In making this fact evident, Wilson wanted to consider the “moro’ [Black] view” in the hopes of addressing the myths and realities of Renaissance Venice.[12]

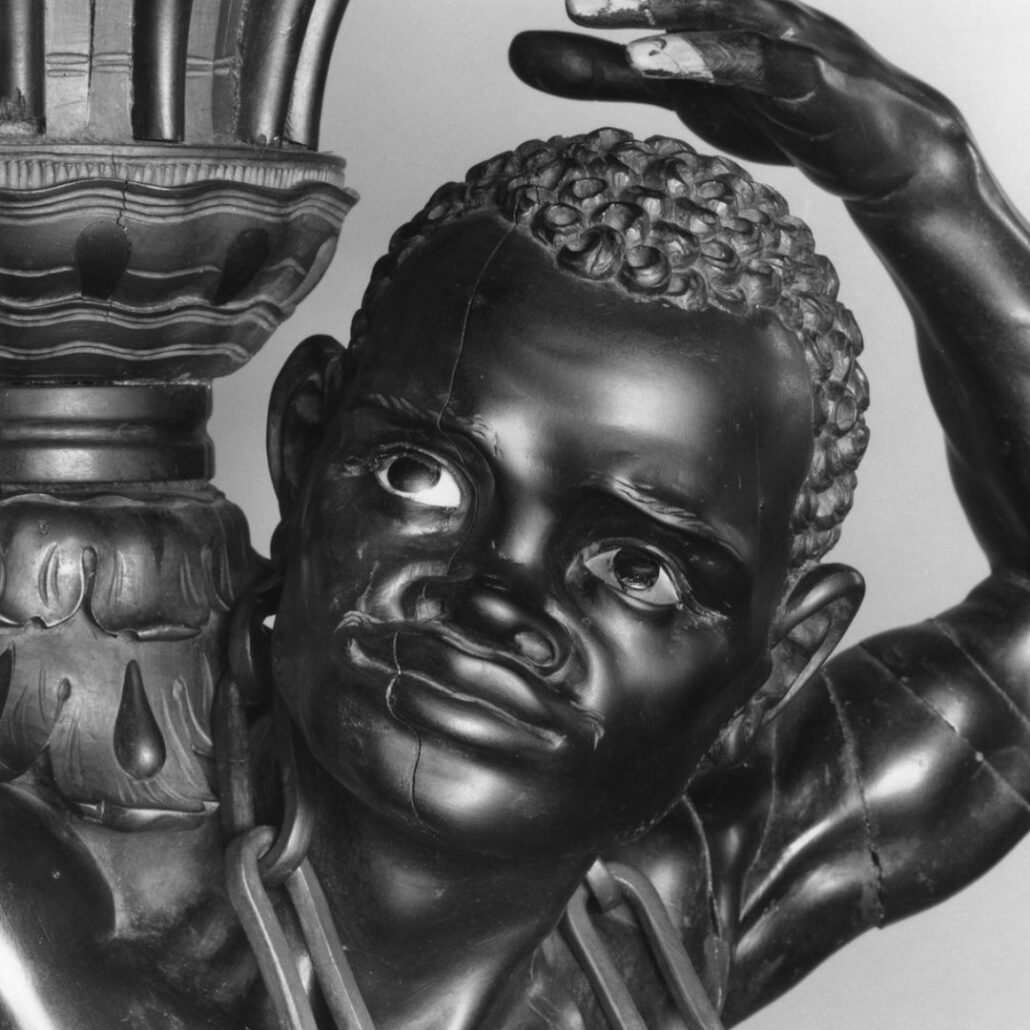

Figures 9-11: Andrea Brustolon, Series of nine porte-vases (“vase supports”) in the form of shackled captives each standing on a base composed of three dragons, 1690-1710 carved ebony wood, height 35.44 in., Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca’Rezzonico

One fantasy of Blackness was the “Blackamoor” which connoted a particular geographic origin and religion.[13] Such a conflation of place with identity is also found in Othello when Desdemona says, “My mother had a maid called Barbary,” with Barbary referring both to a person and to the North African coast (4.3.25).[14] Much as “Barbary” seems ambiguous, so too was “Blackamoor” a loose term that largely encompassed what was not White, European, or Christian.[15] Because of this term’s ambiguity, Early Modern Europe viewed the “Blackamoor” as a representation of the uncivilized or Other.[16] In essence, the “Blackamoor” was created in binary opposition to the Western world. It also manifested in the decorative arts as an ornamental figure used on/in furniture. As used in ornamental contexts, the Black decorative figurine equated people of color with luxury goods to be bought, used, and sold by the White upper class.[17] A traditional example is Andrea Brustolon’s (1662-1732) series of porte-vases (1690-1710) [Fig. 9-14] where the Black decorative figurine appears as the stand for a table meant to hold a decorative vase. In doing so, this example shows how these figures served the household, such as acting as a stand to hold another luxurious object, illustrated the owner’s wealth, and visually asserted the owner’s presumed supremacy over people of color.

Figures 12-14: Andrea Brustolon, Series of nine porte-vases (“vase supports”) in the form of shackled captives each standing on a base composed of three dragons, 1690-1710 carved ebony wood, height 35.44 in., Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca’Rezzonico

[1] John Martin and Dennis Romano, “Reconsidering Venice,” in Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, ed. John Martin and Dennis Romano (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 2; Monique O’Connell, “Voluntary Submission and the Ideology of Venetian Empire,” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 20, no. 1 (2017): 12.

[2] Edward Muir, “The Myth of Venice,” in Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 18, 24; O’Connell, “Voluntary Submission,” 32.

[3] Muir, “The Myth of Venice,” 21; Martin and Romano, “Reconsidering Venice,” 9, 23; Other forms of opulence and connections to Rome were manifested in sculptural objects made with colored stone, most notably onyx, to represent the contrast of clothing and skin. See Joaneath Spicer, “European Perceptions of Blackness as Reflected in the Visual Arts,” in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe ed. Joaneath Spicer (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012), 48, 50.

[4] Edward Muir, “Images of Power: Art and Pageantry in Renaissance Venice,” The American Historical Review 84, no. 1 (Feb. 1979): 33.

[5] Muir, “Images of Power,” 36.

[6] Martin and Romano, “Reconsidering Venice,” 3.

[7] Muir, “The Myth of Venice,” 13.

[8] Peter Burke, Luke Clossey, and Felipe Fernández-Armesto, “The Global Renaissance,” Journal of World History 28, no. 1 (March 2017): 3.

[9] Francesco Bonami, “I Have a Dream,” in Dreams and Conflicts: The Dictatorship of the Viewer, ed. Francesco Bonami and Maria Luisa (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 2003), xxi-xxii.

[10] Bonami, “I Have a Dream,” xxi.

[11] Goncharov and Wilson, “Interview,” 22-23; Although sometimes these portrayals were realistic, like the images of Black gondoliers. See, Kaplan, “Local Color,” 12.

[12] Goncharov and Wilson, “Interview,” 23; “Moro” is Italian for “dark” but also used to reference Moors.

[13] Ella Shohat, “The Specter of the Blackamoor: Figuring Africa and the Orient,” The Comparatist 42 (October 2018): 158; Nandini Das et al., “Blackamoor/Moor,” in Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), 40.

[14] William Shakespeare, Othello: The Annotated Shakespeare, ed. Burton Raffel (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 170.

[15] Childs, “Sugar Boxes and Blackamoors,” 160; Daniel Vitkus, “Othello, Islam, and the Noble Moor: Spiritual Identity and the Performance of Blackness on the Early Modern Stage,” in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 227.

[16] Shohat, “The Specter of the Blackamoor,” 160-61.

[17] Shohat, “The Specter of the Blackamoor,” 174, 172.