Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room: Community Building in Action

Conclusion

The Obliteration Room (2002-present), created first as an installation aimed at children, has evolved over the past 20 years to target a different age bracket and, consequently, has increased in both size and popularity. What began as a child-focused installation made with children’s expected sizes and need of interactivity in mind for the Children’s Art Center at the QAGOMA, over time, morphed into a full-sized replicate domestic interior spatially suited to accommodate adults. In part, due to Kusama’s branding and due to the changing social media landscape, the artwork meant for children then changed into a fully focused adult artwork. By only changing the size of the room and the furniture included in the later installations of The Obliteration Room, Kusama made it clear to adult audiences that this artwork was meant for them while still indicating that they should experience it in a children’s headspace. The work changed physical size, but the goals of play and community building remained the same. The intentions of the piece, but also of the museum industry, have then changed in relation to the changing contemporary economic system and desires of an audience inundated with social media and the digital age. [1] It seems likely that both changed at the same time, due to a societal shift in the internet age, rather than one changing first. [2] Society required that museum interactions change, and Kusama’s interactive, child-friendly work was the perfect fit for this new requirement. Museum spaces take into consideration the recent need for physical social spaces and have acquired artwork like The Obliteration Rooms to cater to these reformed audience demands. As a result, Kusama and her artwork have now become, in some ways, part of the experience and entertainment economy.

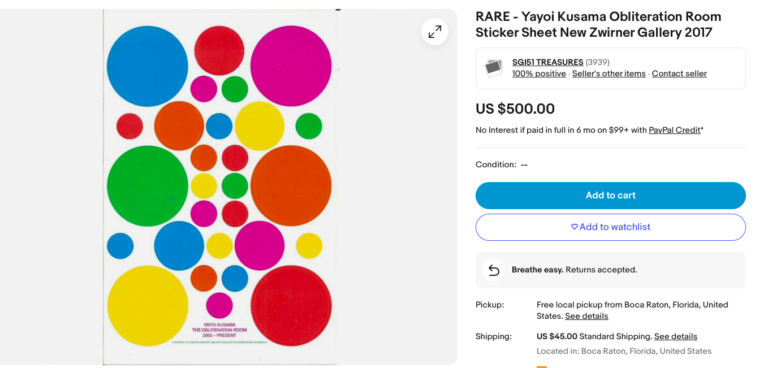

Kusama’s Obliteration Room and her mirrored environments arguably influenced the relatively recent trend of “interactive museums, photo spaces, and experiences” such as Meow Wolf, the Museum of Ice Cream, and the Van Gogh Experience.[3] In both types of spaces, audiences are treated as the “users” of a consumer product, and thus, the institutions cater to their preferences, creating “pleasurable, non-confrontational” environments and emphasizing interactivity with the spaces.[4] The experience of the museum is slowly becoming like these types of interactive experiences, if even differentiated at all, really. Museums are leaning toward incorporating interactive spaces in their galleries in order to increase visitor engagement and revenue, while spaces like the Van Gogh Experience and Meow Wolf are also responding to the same economic stimuli. In a space originally designed to introduce children to art, Kusama’s The Obliteration Room has undergone a contextual shift in which it is simultaneously artwork and experience. In both Meow Wolf and The Obliteration Room, audiences are explicitly asked to touch and interact, can buy tickets, and can buy artwork directly from the exhibition. Visitors may take a piece of the art home with them if they choose to or get away with breaking the explicit rules set for them by Kusama and the hosting museum and keep the stickers from The Obliteration Room or buy a humorously labeled soda from Omega Market, Meow Wolf. Audiences can also participate in the museum-sanctioned practice of taking photos of the art and uploading them to their social media as souvenirs.

Over the 20 years that Kusama’s Obliteration Room has been shown, the environment and expectations of the gallery goer around the work have changed. Due to the museum’s request that visitors share photos of their experience and due to the heightened knowledge of the culture surrounding the experience economy, audiences are no longer surprised by what they may find in Kusama’s installations. Kusama’s brand is well known, ranging from solo exhibitions in major museums to brand collaborations with Uniqlo. Her solo exhibitions are the reasons that audiences travel to museums and are almost guaranteed ways for museums to make money and increase their visitor count.[5] Pictures of the insides of her closed mirrored Infinity Rooms, Narcissus Gardens, and Obliteration Rooms are widespread in popular culture. The idea of a naïve viewer experiencing Kusama artwork for the first time no longer exists. Participants at the gallery are no longer art enthusiasts looking to experience unique forms of community. Although Kusama’s original concept of creating a community joined together in a common goal, audiences interact with The Obliteration Room for something else entirely. Present-day audiences are looking for an “experience,” whether that is a highbrow artistic experience like the one offered by Kusama installations or lowbrow ones offered by the Museum of Ice Cream. The unique ways in which Kusama’s art can be advertised as “experiences” come from a unique cultural shift that coincided with her rise in popularity, where her art can be both community-building art and a “selfie” background.

The Omega Mart experience is a Las Vegas installation created in 2021 by Santa Fe artistic collective, Meow Wolf. The experience recreates the look and feel of a supermarket with humorous or pun-named items which audiences can handle, purchase, and play with. Audiences are also invited to explore the backrooms of the supermarket, which exists only as interactive art gallery and contains no purchasable or removable items.[6] The installation exists in a space between art museum, art gallery, and interactive exhibit, referred to as an “experience.”

Created and produced by Exhibition Hub and Fever, the Van Gogh Experience consists of a bare room with chairs and about an hour of 360° digital projections of Van Gogh’s paintings.[7]

[1] For more artists who critique the museum through participatory art, read Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso, 2012.

[2] Sokolowsky, “Art in the Instagram Age.”

[3] Janet Kraynak, “Therapeutic Participation and the Museological User: The Museum in the Age of Surveillance Capitalism,” In Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life, 115-150, University of California Press, 2020, 138; “… the museum is becoming indistinguishable from any number of cultural sites and experiences, as all become vehicles for the delivery of ‘content.’” “…it potentially undermines the ambitions of the museum as an active, productive public sphere.” “experience is unfolded in proximity to them, so that art serves as an interregnum, a momentary encounter. … The museum thus simultaneously promotes and deflates art.” —Kraynak, “Therapeutic Participation and the Museological User,” 138.

[4] Anna Wiener, “The Rise of “Immersive” Art,” (The New Yorker, 2022).

[5] Julia Halperin and Sarah Cascone, “Anatomy of a Blockbuster: How the Hirshhorn Museum Hit the Jackpot with Its Yayoi Kusama Show,” Artnet News 2017, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/yayoi-kusama-hirshhorn-museum-959951.

[6] Meow Wolf, https://meowwolf.com/about.

[7] Van Gogh Washington DC Exhibit, https://vangoghexpo.com/washington/#tickets.