Part 2: Later Iterations of the Obliteration Rooms

Changed and Unchanged

Most recently, Kusama installed The Obliteration Room at QAGOMA in 2011-2012, the Tate Modern in 2012 (and again in 2022 with Uniqlo Tate Play), the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in 2017, the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2018, the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara, Indonesia (MACAN) in 2018, and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA in 2018 through 2019.[1]

By only changing the size of the room and the furniture, Kusama was able to communicate to her adult audiences that this formerly child-focused artwork was meant for them to place them into a similar playful headspace like the ones that they experienced as children. She kept the child-friendly stickers and even some of the children’s toys, like the plastic and plush animals included in both the original room and the Tate Modern. These larger adult spaces are meant to signal a domestic living space in which both adults and children live. Kusama’s Obliteration Room represents an idealized domestic space in which a family lives with their children. Children may have been sized out of the room, but they are not forgotten. The original goals of the artwork, to create a space where play and community building through a common goal can flourish, remain intact after the change.

Each of these later iterations varied slightly, from the types and shapes of the furniture and decorations included to the size and shape of the gallery space, as well as at least two different sticker sheet patterns. As with the layout and specific elements in the room, the conditions of interactivity in the room also depended on the museum and curator. For example, in the 2012 version assembled in the Tate Modern in London, viewers were allowed to sit on and manipulate the furniture, while in the 2018 showing of The Obliteration Room at the High Museum, interaction with the furniture was limited.[2]

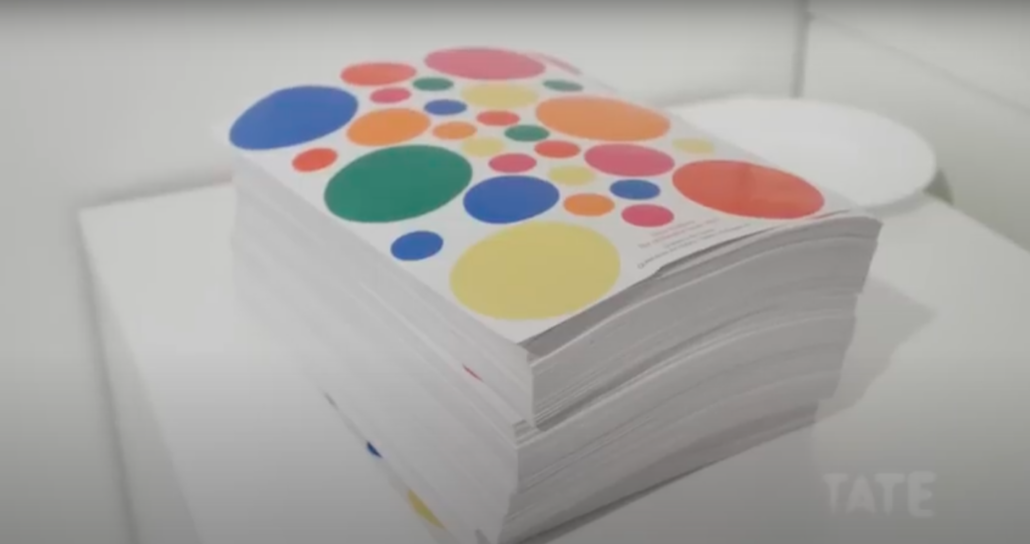

Yayoi Kusama, The Obliteration Room, 2012. Tate Modern, TateShots.

Credit to Tate Modern, TateShots in video linked below.

Video still of wall patterning.

Yayoi Kusama, The Obliteration Room, 2012. Tate Modern, TateShots.

Credit to Tate Modern, TateShots in video linked below.

In 2011-2012, the Obliteration Room was once again installed at the QAGOMA, this time as a fully enclosed space with adult-sized furniture. Whereas the first 2002 Obliteration Room was installed inside a larger gallery space as a small room with three half-walls, an open doorway, and no ceiling, the 2011 iteration was its own room in the gallery. In this later installation, Kusama included two conjoined spaces of a Western home that connected in one large room. The furniture was no longer child-sized and comfortably fit full-grown adults. The first section of the 2011 room included a dining area complete with an empty wooden bookshelf, three overhanging lamps, a set dining room table with plates, cups and teacups, bowls, six wooden chairs, and a painted white potted fiddle-leaf plant set on an elevated tripod stand. The second section of the room contained a living room scene with two couches with pillows and cushions facing each other, a coffee table, a desk and chair set, and a large bookshelf, which covers the entire end wall decorated with framed white pictures and other assorted knick-knacks traditionally found in Western homes like plates and books (Figs. 5 and 6).

Each time the Obliteration Room is displayed, the size of the room differs as it is determined by the museum and curator. The hosting venue is also responsible for sourcing the furniture items and objects displayed, as these are never shared between venues. Furniture items and objects are either disposed of or recycled following sticker removal after the end of the exhibition period.[3] Although each venue can cater The Obliteration Room to their specific location and/or time period, each of the iterations of The Obliteration Room follows the same basic style of plush or wooden Western furniture, which is either locally sourced or brand-identified, as in the 2022 Uniqlo sponsored version. The design intent appears to create the feel of a typical domestic living space in both scale and content everything within the space is painted white by the staff at the hosting venue.

Image: Reece Straw. Courtesy of Tate Modern. https://www.stirworld.com/see-news-yayoi-kusamas-famed-the-obliteration-room-comes-back-to-tate-modern.

At the Tate Modern in 2012, The Obliteration Room consisted of a single gallery space with furniture indicative of either a living room or family room or some amalgamation of the two. The space had a large dining table and chairs, bookshelves, stools, children’s toys, a rocking horse, a basket, a drop-zone (a purse, shoes, and a table), a children’s walker, plush toys, and pillows. In a video produced by TateShots and promoted by the museum as an advertisement, the director of the Tate Modern and curator of Kusama’s exhibition, Frances Morris, states that visitors are invited to place the stickers “anywhere they like in the room, according to any pattern, any idea they have…anything they like they can do with the stickers.”[4] Taking the official Tate Modern video and her own interview at face value, Morris has outwardly chosen to change the rules governing the artwork. Morris’ different, less strict instructions for patterning enabled differences in appearance between the stickered walls of the Tate and the other versions of the installation. As seen in the video, some areas of the walls of the Tate gallery were covered in large swaths of the same-colored stickers, allowing for large blocks of patterned color (Fig. 22). Ten years later, in the 2022 Obliteration Room at the Tate Modern, participants were again presumably allowed more freedom than originally allowed in the 2002 rules, as the dots were used to create a large rainbow pattern that spanned multiple rooms (Fig. 23).[5] This later version of the installation marked the first time that the artwork had transitioned back to its original commissioning purpose as an installation with short walls meant for surveillance that was not entirely an enveloping space.

In the same 2022 exhibit in which audiences were allowed more freedom, the Tate Modern partnered with the Japanese brand UNIQLO to both sponsor and create their version of The Obliteration Room. [6] The 2022 room was also advertised specifically as a “UNIQLO Tate Play” event for audiences of all ages.[7] This branding acted as a way for the Tate to fund the exhibition of the Kusama work, commodifying the work and outwardly signaling that this event included children through the slogan “for audiences of all ages.”[8] With marketing indicating that the space was firstly meant for children, the Tate promoted a return to the original conditions of the work’s installation, i.e., a children’s exhibit. The Tate even erected a modified version of the shorter, non-encompassing walls of the first edition room (Fig. 24). These walls are short enough that they do not touch the ceiling but are not so short as to be child-sized as in the 2002 version when they were approximately 4 to 5 feet tall. The photographs were taken from a bird’s-eye view in which the entire installation could be seen, but which also replicated the effects of a parent in 2002 peering at their children over the installation wall to make sure they were doing okay.

Images provided by the Hirshhorn Museum.

Images provided by the Hirshhorn Museum

The Hirshhorn Museum’s Obliteration Room from 2017 was part of the blockbuster exhibition “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors,” which welcomed 475,000 visitors, which was the highest spring visitation in the museum’s history and double the average attendance for that period.[9] The installation consisted of a single room in the gallery, which acted as a combined living room and kitchen space (Fig. 23 and 24). The space included explicitly adult objects such as a wire rack with wine bottles, a coffee machine, and a blender, as well as other decorative objects like a fruit bowl with fake fruit and a working piano and bench, all of which were coated in white paint. Audiences were invited to sit on and interact with the furniture as well as play the piano, resulting in the stickers on the piano keys and underfoot being worn down by repeated exposure or rubbing.[10]

Kusama’s Obliteration Room in the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), exhibited in 2018, was spread across two gallery rooms, an “indoor” space divided into a dining room and a living room and an “outdoor” space signifying a backyard area (Fig. 25 and 26).[11] In the “outdoor” space, the AGO incorporated two adult-sized wooden chairs and one child-sized plastic lawn chair, a bike, a fire pit (including wooden logs and wire cover/grate), and a trellis complete with painted white fake plants hanging from the wall. The indoor living room and dining room were separated from the outdoor area by a large, plush couch turned to face the four open doors that opened into the “outdoor” room. The couch created a partition between the living and dining room areas, making the space appear to have three distinct areas, unlike previous iterations in which the dining and living rooms formed one complete space. The AGO’s Obliteration Room also had a slim desktop computer and keyboard, specific to the year in which the work was seen versus the year in which it was devised. (Fig. 12).

Image credit: Lana @ TravelSavvyGal, June 1, 2017. https://www.travelsavvygal.com/kusama-art-exhibitions/?cn-reloaded=1.

Timelapse Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=an0g93vw5j8.

High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA.

Image credit Alexis Shulman.

The AGO, like the Hirshhorn, used the six-sticker sheet as opposed to the larger twenty-eight-sticker sheet. The smaller sheet does not include pink dots while the larger sheet does (Fig. 6). The lack of pink changes the entire color scheme of the room. Rooms with six stickers have a more primary rainbow appearance, while rooms with the twenty-eight-sticker sheet have an extra-spectral rainbow color scheme.

In her 2002 drawing, Kusama pictured children placing stickers on their bodies, entwining their polka dotted selves with the polka-dotted space (Fig. 4). Somewhere along the years that the work has been exhibited, Kusama’s instructions or intentions have been changed for an unknown reason. These changes allow for different amounts of options and freedoms for stickering for participating audiences. Audiences with more lax rules may apply stickers to their bodies or even in figurative patterns on the walls of the room. For example, in 2018, at the AGO, participants were explicitly instructed not to place stickers on their bodies. [12] The prohibition of patterning and representational dotting are the consistent rules penetrating all the iterations of The Obliteration Room, though.

In terms of the stickers, the exact sheet of stickers depends on the hosting museum and is either a sheet of six red, orange, yellow, green, and blue stickers or a sheet of twenty-eight stickers of all the aforementioned colors plus an extra pink shade.[13] Both sheets have three sizes of circular stickers – small, medium, and large—but the number of each varies the given total number of stickers on the sheet. At the end of the exhibition run, almost every square inch of the previously painted white areas, including the ceiling, floor, and walls, were covered with stickers. Some of the stickers overlap with others some use the smaller stickers to create designs within the larger stickers and follow snaking, linear clusters. In some spaces, audience members have collaborated to cover large areas with the same color stickers. Some stickers have been ripped into halves and thirds to further create shapes and designs onto the white spaces. Some visitors have even utilized the stickers to create their own three-dimensional additions to the rooms, e.g. creating chains that hang off the lamps (Fig. 28). The smaller, rounded shape of teacups means that larger stickers hang off the rim or bunch up due to air bubbles. The surfaces also change the adherence of the stickers. Fabric surfaces tend to attract and hold fewer stickers than the walls, for instance. Consequently, The Obliteration Room will differ in appearance every time it is installed since it is the gallery visitor, not just the artist, who creates the visual appearance of the work with their sticker placement. Each sticker contributes to the collective of stickers used over the course of the exhibition. The work is technically always incomplete and is not a self-sufficient and autonomous entity.[14] There is no singular outcome, and no singular “finished” appearance. At the end of the allotted exhibition time, the gallery staff comes in, removes the stickers, erasing the work of participants, and allows the work to be temporarily destroyed until a future reconstruction.

Scholars Adan Jerreat-Poole and Sarah Brophy noted that amongst the 2018 #InfiniteKusama selfies, participants recorded themselves circumventing the rules by placing stickers on their own bodies. Such pictures comprise evidence that rule-breaking existed alongside people following the rules and listening to staff instructions.[15] Such specific rules provide audiences with the paradox that by explicitly instructing audiences what not to do with the stickers, the staff are giving audiences exact examples and new ideas of what can be done with them. Rule-breaking also implies that museum staff are lax with the rules. It shows the realistic actualization of mediated environments. Kusama and museums can plan for all possible outcomes, but the actual occurrences will always vary from the plans. Participants similarly broke the dictated rules at the Zwirner Gallery installation when they removed stickers from the gallery and placed them on the brick walls outside of the exhibition (Fig. 32).

Furniture, white paint, dot stickers. Dimensions variable. The Obliteration Room (2002 to present) first commissioned by Queensland Art Gallery, Australia.

Collection of Queensland Art Gallery. © Yayoi Kusama.

Photos by AGO Image Resources.

Furniture, white paint, dot stickers. Dimensions variable. The Obliteration Room (2002 to present) first commissioned by Queensland Art Gallery, Australia.

Collection of Queensland Art Gallery. © Yayoi Kusama.

Photos by AGO Image Resources.

Furniture, white paint, dot stickers. Dimensions variable. The Obliteration Room (2002 to present) first commissioned by Queensland Art Gallery, Australia.

Collection of Queensland Art Gallery. © Yayoi Kusama.

Photos by AGO Image Resources.

During the 2015 exhibition at the David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea, New York, Obliteration Room stickers left the space of the installation. They were taken outside by audiences and placed on the brick exterior of the gallery (Fig. 32). There are more than twenty-eight stickers in Figure 32 alone, meaning that many people placed stickers on the outside walls. At the very least, the new outdoor “obliteration wall” consisted of two twenty-eight sticker pads, assuming that at least one full sheet was saved and used outside. In this way, Kusama’s art inspired the act of stickering to extend beyond her art piece and to continue the world outside the museum.

Also, at the Zwirner Gallery, Kusama’s Obliteration Room again consisted of a room-within-a-room installation. The installation was part of her 2015 solo show at the gallery, Give Me Love. For this, a full-sized single-story suburban house was built inside the gallery.[16] Both the overhead door of the room that held the house that contained the Obliteration Room and the front door of the Obliteration Room itself were left to accommodate a large line of guests. This means that the gallery itself was not an enclosed space, and visitors could see the line of people waiting outside, breaking the illusion of a fully encompassing space. (Fig. 34). But at the same time, the long lines fostered a sense of community within the exhibition, or at least the feeling that the participants were not alone in their stickering of work.

Kusama’s popularity has led to larger audiences at museums that are trying to appeal to contemporary viewers who want experiences, which then means lines and waiting lists for her rooms. Large lines change the ways in which The Obliteration Room is interacted with. Community can be created before, during, and after interaction with the installation.

The exterior of the Obliteration Room Zwirner house was not painted white and was instead left in its natural colors. Only the interior was painted white. The exterior was complete with siding, windows, and shutters; the American flag hung on a flagpole, a mailbox, and the house number “9393” spelled out in separate metal numerals.[17] The house also had a small patio with a plastic lawn chair and a set of concrete steps leading up to the entrance followed by a welcome mat in the doorway and a lit porch light. The inside of the house was then comprised of white rooms and white furniture where stickers from the twenty-eight-dot sticker sheet could be placed. The inside looked like the previous Obliteration Rooms, with a large combined single room that consisted of a living room, dining room, and kitchen furniture. Photographs documenting the installation reveal a lack of stickers on the exterior of the home, making it reasonable to assume that stickers were only allowed to be placed on the white interior. This 2015 Obliteration Room was meant to imitate an undeniably American space, from the traditional suburban style architecture to the national flag hanging from the façade, to specifically appeal to American Zwirner Gallery participants. This is a departure from its original instructions for a modern style domestic space. Following that, I conclude that the decor is meant to reflect the country in which it is based. Appealing to participants with homes and furniture that would be familiar to them allows for the entirely white room to feel even more unfamiliar after participants enter the house.

Yayoi Kusama: Give Me Love Exhibition, 2015. Credit to Lyman Creative Co.

https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery

David Zwirner Gallery, Chelsea, NY.

Image credit of David Zwirner Gallery.

https://www.davidzwirner.com/exhibitions/2015/give-me-love#/installation-views

Image credit to Lyman Creative Co.

https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery

Image credit to Lyman Creative Co. https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery.

Image credit to Lyman Creative Co. https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery.

This full-sized home built to house The Obliteration Room is the closest that an adult-sized Obliteration Room has come to recreating the feel of Kusama’s drawing of an idealized 2002 child-sized first installation. Kusama initially planned for the Obliteration Room to be a fully immersive experience where participants could feel like they were experiencing the obliteration of both themselves and the home they were in. In her 2002 iteration, changes were made, which meant that the installation would be child-safe but prevented a full immersion into the artwork. The 2015 Zwirner iteration of the artwork not only had a roof but also existed as a separate space from the other rooms in the Zwirner Gallery and could be considered a complete immersion (Fig. 33). Whereas prior installations were within a gallery space, meaning that audiences would experience the installation as if it was another room in the gallery, Zwirner participants were given the opportunity to experience the installation as if it were its own separate space, away from the gallery. Previous Obliteration Rooms that existed as a single room inside the museum meant that audiences would walk into and out of them through another section in the gallery. Although they allowed audiences to feel as if they were leaving the gallery, this illusion was then broken when the participant walked into the next room. However, since the Zwirner Gallery Obliteration Room was its own separate house, audiences could experience the artwork without ever feeling as if they were still in an art museum.

Yayoi Kusama, David Zwirner Gallery, Chelsea, NY, 2015.

Image credit to Lyman Creative Co. https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery.

Yayoi Kusama, David Zwirner Gallery, Chelsea, NY, 2015.

Image credit to Lyman Creative Co. https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery.

[1] For another example of The Obliteration Room outside of the Unites States, see the room installed in the Museum MACAN – Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara, Indonesia for the exhibition Yayoi Kusama: Life is the Heart of a Rainbowthat lasted from May 12 – September 9, 2018, and the YouTube video of the installation: https://youtu.be/LkjUFGzYm9c; Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama: Life Is the Heart of a Rainbow, Edited by Russell Storer, 1st ed. National Gallery Singapore, 2023, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.3385988.

[2] Gray, “Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room | TateShots,” [0:44]. The limited interactivity in the 2018 installation is demonstrated in a time-lapse video, which does not show anyone sitting on the chairs or furniture or otherwise physically manipulating the space.High Museum of Art, “[3 Month] Timelapse of Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room at The High Museum of Art,” posted February 25, 2019, 1:16.

[3] Tunny, email message, August 22, 2023.

[4] Lillian Gray, “Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room | TateShots,” (Tate Modern, 2012), YouTube. (0:44); TateShots is the name given to the videography department at the Tate Modern in London.

[5] Anna Piper, “’The joy of this exhibit is how much it invites play’: the Obliteration Room at the Tate Modern.”

[6] Vatsala Sethi, “Yayoi Kusama’s famed ‘The Obliteration Room’ comes back to Tate Modern.”

[7] Nick Wichmann, “Kusama’s Obliteration Room Comes to Tate Modern for UNIQLO Tate Play – Press Release.” (Tate Modern, 2021).

[8] The UNIQLO branding may have also led to a difference in rules communicated to the participants, but it is unclear.

[9] Julia Halperin and Sarah Cascone, “Anatomy of a Blockbuster: How the Hirshhorn Museum Hit the Jackpot with Its Yayoi Kusama Show,” (Artnet News, 2017).

[10] The sticker sheet for the Hirshhorn installation included six different stickers of three different sizes, two reds and one of each orange, yellow, green, and blue (Fig. 14). In this exhibition, Kusama has chosen to stick to five of the colors in the rainbow, but has chosen two of the same red shade, rather than fully completing the rainbow with purple.

[11] Art Gallery of Ontario, “Yayoi Kusama’s The Obliteration Room,” YouTube, April 9, 2018.

[12] Adan Jerreat-Poole and Sarah Brophy, “Encounters with Kusama: disability, feminism, and the mediated Mad art of #InfiniteKusama,” Feminist Media Studies 21, no. 6 (2021): 911.

[13] I have been unable to find exact instructions for the reasoning behind the colors and am therefore assuming that they then are meant to be the colors of the rainbow.

[14] Bishop specifically relays the idea of “incomplete” art to the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ ‘candy spills’ in which the work is always incomplete as it relies on audiences and museums to both actively take apart and assemble the candy pieces that the work consists of; Bishop, Installation Art, 115.

[15] “In some of the #InfiniteKusama selfies, we discovered evidence of rule-breakers who did place the stickers on their own bodies, mapping out the limits of this [the AGO’s] control. The circulation of these acts of resistance online alongside the images of “good” patrons who followed the rules and took exhibition approved photos shows us the critical potential of mediated affective encounters, their capacity to generate momentary disruptions…” –Poole and Brophy, “Encounters with Kusama,” 911.

[16] I have not found a full 360-degree view of the exterior of the house. It would be interesting to see if it has a backyard space or not, as to compare it to the indoor “outside” of The Obliteration Room at the AGO. I am also curious as to how the rules were communicated to audience members. I am assuming that they were explicitly told not to place stickers on the outside, rather than the idea that stickers were, instead, removed from the exterior, after participation.

[17] I have also yet to see what the meaning of “9393” is to Kusama.