Part 2: Later Iterations of the Obliteration Room

Community Building

“Community” in The Obliteration Room can refer to the combined sticker remnants left by the participants over the course of the entire exhibition of the installation and to the physical bodies of the participants in the space. Claire Bishop, in Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, describes this trend towards art and community building as a way for artists to turn previously considered “viewers” into “co-producers” or “participants.”[1] Bishop argues that although these are ideals and not actualized realities, they are created with the aim of placing pressure on conventional modes of artistic production and consumption under capitalism. She adds that community-building art is an attempt to return to a communal society accompanied by a utopian rethinking of the potential of art.[2]

By bringing strangers together to achieve a common goal within a domestic interior, that is, to “obliterate” the white space with colorful dots, Kusamaakes them share a once private space and heightening the sense of community. Kusama has most likely chosen to transform the gallery setting into a home interior (and exterior in the case of the Zwirner Gallery installation) rather than leaving the gallery intact or creating a more formal space like a classroom or office, to make public the previously private space. Though it is possible that the domestic interior was originally meant to create a familiar and, therefore, safe, space for children, it has picked up additional meanings over time such as creating a space in which adults can regress to a childhood state of mind. It should be noted that Kusama’s created community is only dismantled when the installation is torn down at the end of its exhibition and the stickers are removed. It is not dismantled when the physical bodies of the participants leave the space. Furthermore, the community in The Obliteration Room may exist as a group of participants, but they are ultimately led and instructed by Kusama, who has the final authoritarian say over the results. They are allowed to make their own choices, though any choice that violates Kusama’s strict set of predetermined rules would be removed from the installation.

Creating community through artwork inspired Kusama to stage naked Happenings and “body festivals” from 1967 through 1969. Her Happenings and her Obliteration Room function in much the same ways in terms of both visual aesthetics and institutional critique. Kusama was explicitly against the Vietnam War and vocal about her opposition, especially because of her experience growing up in Japan during wartime.[3] Kusama used her art as an anti-war protest, staging naked anti-war Happenings in New York outside of the traditional gallery setting that included herself, other spontaneous volunteers, as well as other figures from the art world which she called the Naked Body Festivals. Walking Piece (1966) and 14th Street Happening (1966) marked the first significant moments when the artist’s image became an explicit part of her work and signaled her shift from sculpture and installation to performance and happenings. Her Happenings, unlike her earlier performances, relied on the participation of groups of young people and curious onlookers, who were originally charged for entry.[4] These early art pieces also existed as a form of institutional critique since they existed as art outside the space of the museum. They could not be commodified and were instead meant to create community. Her later Obliteration Room iterations followed a similar trajectory as Kusama asked participants to “obliterate” or obscure the white gallery walls and white-painted furniture with colorful dot stickers. Kusama’s created community within the Happenings was fundamentally different than the community created within The Obliteration Room, however. The Happening works are entirely reliant on the participants, they would not exist without their physical bodies in the work. The participants of The Obliteration Room can leave anytime, and the piece will continue. Participants in the Happenings cannot. On the other hand, in The Obliteration Room the community created can be visualized by the sticker remnants. Once the physical bodies of the participants leave the room, their stickers still exist within the space as proof of a formed community.

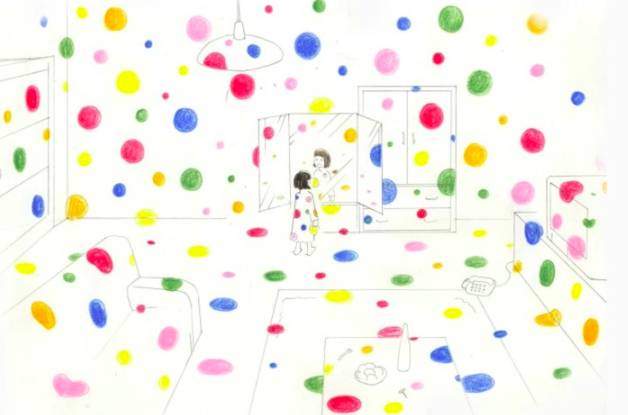

Kids’ APT Interactive Artwork, Gallery 3, QAGOMA.

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia.

Copyright Queensland Art Gallery, QAGOMA. Imaging Photographer: Natasha Harth.

In the Happenings, participants follow Kusama’s instructions to remove their clothes paint one another with colorful dots while jazz music played. They enacted Kusama’s ideas of obliteration, self-destruction, and the collective.[5] Kusama’s foray into Happenings and communal art also originated from the fact that she was feeling alienated and isolated within the white, male-dominated art world. Her later installations would have the same goal of creating a community between interacting members. Like these Happenings, her Obliteration Rooms later exist as shared environments that speak to a shared public communal sphere rather than an individual private world, a sentiment that would remain true throughout her entire career.[6]

Much like her earlier Happenings, The Obliteration Room is a participatory installation, meaning that audiences are asked to walk into the space and contribute to the artwork.[7] Kusama’s original Obliteration Room was originally meant to help children explore art through forms that cater to them such as tactility and physically smaller furniture that was designed for them. The installation, however, has now changed meaning through a change in both demography and size. What once was a work designed to let children experience art and museums now represents a relational art piece that allows adults to interact with the work.

The Obliteration Room is not created by a single participant. Rather, it is an amalgamation of those who have attended the exhibition and placed their stickers onto the space. Participation in The Obliteration Room can be quantified both by data provided by its hosting museum and by time-lapse video taken throughout its exhibition.[8] In its two most recent displays of The Obliteration Room, the QAGOMA received 304,265 visitors who used 117,175 sticker sheets between December 6, 2014–April 19, 2015, and received 435,151 visitors who used 148,500 sticker sheets between October 14, 2017–February 4, 2018.[9] This data shows the popularity of the installation, as well as allowing a quantifiable number of potential contributing participants within the space over the exhibition period. This proves that Kusama’s exhibits are reaching beyond the art world and breaching into popular entertainment. Because of this, participants likely have outside knowledge of what to expect when experiencing a Kusama exhibition. It also means that a larger community is created within the exhibition due to the increased number of stickers. Although applied individually, once placed, stickers are not individually viewed. This volume of stickers represents an archive of participation, in which audiences are not just making individual contributions but are part of a larger collective that is asked to participate in the work. Lastly, the greater number of participants also changes the look of the installation. More stickers mean that more of the physical area of the room is covered with colored dots rather than the white of the walls of the furniture.

Yayoi Kusama, David Zwirner Gallery, Chelsea, NY, 2015.

Image credit to Lyman Creative Co. https://lymancreativegroup.com/blog/yayoi-kusama-at-the-david-zwirner-gallery.

The Obliteration Room acts both as a space and a time to be walked through. Commenting on the installation and creating community occur at the same time as seeing and perceiving surroundings.[10] The room can then be considered time-based art, in which audiences and artwork are constituted in a particular location at a particular time.[11] The artwork is then marked by a condition of non-availability, viewable only at a specific time, and once it ends, all that remains is documentation, which cannot be confused with experiencing the art.[12] The artwork lasts from the day it is open to the public until the day it is closed. After the exhibition, all the stickers are removed, and the furniture and objects are disposed of or recycled if possible.[13] Removing the stickers is the only way to deconstruct the created community. The work and community are not reliant on the presence of the physical body within the space. It is instead reliant on length of the exhibition and the actions of the museum.

Additionally, Kusama’s participatory installation appeals to the audience’s sense of responsibility. Audiences’ contributions add to those of others, creating equal acts of participation within the work. The visitor must understand that his/her gestures contribute to the construction of the work.[14] Thus, the work can be considered “open,” reliant on the definition by scholars Hyun Jean Lee, and Jeong Han Kim in “After Felix Gonzalez-Torres: The New Active Audience in the Social Media Era.” “Open,” by their definition, refers to the idea that the museum visitors feel that they can interpret the piece in any way and add to the piece in any way that they desire. As long as the artist’s instructions are not communicated to the audience by the hosting museum, the work appears totally “open” but, in reality, is not.[15] While the size, shape, and colors of the stickers have already been predetermined by Kusama, there is an infinite realm of possibilities in which areas and audiences can place their stickers. The importance of this is that, even though the work is considered “open,” the artist has determined in advance the type of participation within it that the audience may have.[16]

“Open” artworks relate to a sense of authority between the viewer and the museum guards. Aside from enforcing the artist’s rules, museum guards also monitor the physical activity of the participants. Museum visitors may also assume that every action they make is monitored by the guards either physically in the room with or after them and those watching on the security cameras.[17] The proximity to “openness” that the work achieves is then based on the individual’s personal code of ethics. Engaging with art in museums often implicitly means not touching or physically interacting with the artwork. By taking this idea and flipping it, Kusama has created an uncomfortable or exciting scenario for audiences accustomed to a particular experience within the museum space. Children who are not acquainted with museum rules may feel more comfortable interacting with artworks than adults who are aware and respectful of traditional museum rules. In addition, within the “open” art piece, there still exists the dominance of artist’s specifications, then the enforcement by the museum staff and guards, and finally, audiences who participate in the creation of the work. The participants are only in control of what they do with their own stickers and cannot control what happens to the room after they leave. Unless an audience member returns to revisit the work, they will never know that their inclusions have been discretely removed by museum staff, in keeping with the periodic maintenance of the work.

Yayoi Kusama APT 2002: Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art Mirror/Infinity Room.

QAGOMA. Copyright: Queensland Art Gallery, QAGOMA. Imaging Photographer: Natasha Harth.

Claire Bishop argued that Kusama used “mimetic engulfment” by applying polka dots to obliterate herself and her audience, allowing for the blending of the self and the surrounding environment.[18] Bishop defines this phrase as mimicry of one’s environment, like in camouflage. Beginning with her staged photographs of herself sitting amongst her phallic sculptures, Kusama was familiar with the concept of art and the artist acting as one unit. Kusama typically is photographed in front of her art pieces in polka-dotted outfits, allowing her to blend in with her art in a full realization of her self-obliteration concept (Fig. 11). When Kusama began her career in New York in the 1960s, the idea of camouflage would have been interpreted as a direct anti-war sentiment. Unless they are wearing polka dots or apply the stickers to their own bodies, audiences of The Obliteration Room will not experience the same immersion into the art. This immersion, however, can happen to the audience if they apply the stickers to their bodies, as children may choose to do. The application of stickers to one’s body is not explicitly outlawed or included in the instructions. It can be assumed that many adults forgo this “mimetic engulfment” experience, as Bishop refers to it, of applying dots on themselves as it is associated with more childish behavior or because they prefer a more “permanent” application of the dots to the physical installation. In the installation, adults may find their sense of imagination is heightened and that they will engage with more “childish” desires and actions.

Works that are theoretically “open” or, at least, appear to be fully open to public intervention inspire a pluralistic, collective worldview amongst its participants who are confronted with the realization that their contributions are a smaller part of a larger collective. The Obliteration Room has a multiplicity of possibilities that are only limited by Kusama and the hosting museum’s guidelines. It also implies that no audience member is more important than any other. The space is democratic in the way that all audiences, no matter their age, are asked to equally participate by adding the same predetermined number of stickers. Audiences are asked to work together in a community to create a single piece of art. The community is also brought together by a single common goal: creating the art piece. The work, however, is not fully democratic. Kusama acts as leader, predetermining the actions that can be taken and how the actions will look in the space.

Kusama’s Obliteration Room, first created in collaboration with the QAGOMA specifically as art meant for children, a traditionally overlooked group of museum attendees, allows children to experience high art in interactive ways that allow them to touch and feel the artwork in order to learn about it. In upcoming iterations, Kusama and collaborating museums would change the artwork so that it was focused more on adults than children, but the first iteration was purely designed with children in mind, with furniture and activities that would be familiar and comfortable to them. Her work then is a visual testament to the community created, showing a collapsed timeline of all the participants through the stickers they placed on the piece.

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia.

[1] Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso, 2012, 2.

[2] Bishop, Artificial Hells, 2.

[3] Lenz, Kusama – Infinity.

[4] Yayoi Kusama, Frances Morris, and Jo Applin, Yayoi Kusama / Edited by Frances Morris; with Contributions by Jo Applin … [et Al.] (London: Tate Publishing, 2012): 287.

[5] Kusama and Rosenthal, Yayoi Kusama: A Retrospective / Edited by Stephanie Rosenthal, 23.

[6] Jo Applin, “I’m Here, but Nothing: Yayoi Kusama’s Environments,” In Yayoi Kusama / Edited by Frances Morris; with Contributions by Jo Applin … [et Al.] (London: Tate Publishing, 2012): 287.

[7] Jo Applin, “I’m Here, but Nothing: Yayoi Kusama’s Environments.” Yayoi Kusama / Edited by Frances Morris; with Contributions by Jo Applin, Juliet Mitchell, Frances Morris, Mignon Nixon, Rachel Taylor, Midori Yamamura, (New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2012): 287.

“Her 1968 rallying cry “Let’s get to know one another’, is striking, less as an instance of publicity-seeking at a time when she was embracing the free love and happening movements, than as a serious and potentially radical mode of ‘world-building,’ which her environments continue both to imagine and produce.” – Jo Applin, “I’m Here, but Nothing,” 287.

[8] QAGOMA, “Watch as Yayoi Kusama’s ‘The obliteration room’ is transformed,” posted March 10, 2015, Yayoi Kusama: The obliteration room / Children’s Art Centre, Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) Brisbane Australia / 06 December 2014 – 19 April 2015, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, 1:52. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4gQ7Ryt2R8&t=2s;

Quantitative data can be used to address the increased popularity in Kusama exhibits over the years. For example, the 2017 version at the Hirshhorn museum, used 750,000 dot stickers during the 12-week exhibition according to Molly Hermann in the documentary, Seriously Amazing Objects, Season 2, episode 3, “Supersize.” (45:00). Later versions of the project at the QAGOMA, 304,265 visitors used 117,175 sticker sheets between December 6, 2014 – April 19, 2015, and 435,151 visitors who used 148,500 sticker sheets between October 14, 2017 – February 4, 2018, as relayed to me in an email by Jaqueline Tunny.

[9] Tunny, email message, August 22, 2023.

[10] Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, 15-16.

[11] Mallett, “Preventing Predictions,” 19.

[12] Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, 29.

“The artwork is thus no longer presented to be consumed within a ‘monumental’ time frame and open for a universal public; rather, it elapses within a factual time, for an audience summoned by the artist. In a nutshell, the work prompts meetings and invites appointments, managing its own temporal structure.” —Bourriaud, 29.

[13] Tunny, email message, August 22, 2023.

[14] Steve Dietz, ‘Foreword’, in Beryl Graham and Sarah Cook, Rethinking Curating: Art after New Media, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2010, p xiv.

[15] Hyun Jean Lee, and Jeong Han Kim. “After Felix Gonzalez-Torres: The New Active Audience in the Social Media Era.” Third text 30, no. 5-6 (2016): 479-480.

In reference to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ candy spills – “The certificate describes the operative rules for the artist’s work, and according to it, the work should always be refilled with a certain number of sweets at the end of each day. For curators, keeping the work alive is a great responsibility. However, such responsibility rests with the museum, not the audience. Moreover, the certificate may not have restricted the audience’s extended participation. Also, as long as the certificate is kept hidden from the audience, there is no such specific instruction for the audience, and this is the reason why the work appeared totally open.” – Lee and Kim, “After Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” 479-480

[16] Bishop, Installation Art: a Critical History, 127.

[17] Lee and Kim. “After Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” 482.

[18] Bishop, Installation Art, 90.