In the 1870s and 1880s, when Gonzalès started working in pastel, its reception was being transformed by artists and critics alike. This was due in part to its adoption by members of the Impressionist group. The transportability of pastel, and its ability to quickly capture scenes of everyday life, made the medium attractive to Impressionist artists. In the 1880s, pastel received another boost in its reception from the “Rococo revival” spearheaded by critics and art administrators. As a result of their efforts, this formerly disparaged style was recast as an integral part of the nation’s cultural heritage and distinctive identity. [26]

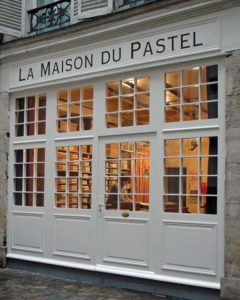

Figure 6. La Maison du Pastel located in Paris, France. Founded in 1720 by Henri Roche. This is the shop where Degas has his pastels crafted.

Several artists included works in pastel among their submissions to the first “Impressionist” exhibition of 1874, including Berthe Morisot, Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet.[27] But it was Edgar Degas whose career and signature style became enmeshed with the use of pastel: he applied this medium to depict typical Impressionist motifs in novel and original ways.[28] His experimentation with pastel became part of his broader usage of unusual media, including monotype, gouache, and distemper.[29] The pastels he used were unconventional in both their chemical composition and the manner in which they were applied. As Laura Kalba notes, Degas steered clear of commercial art suppliers who could not produce pastels that met his individual requirements in terms of color and texture (Fig. 6).[30] Instead, he embraced artificial colors that were used commercially in products such as fabrics for fashion and furniture.[31] These colors, often produced through chemical means, allowed a brightness and vibrancy of color that could not be achieved with other materials or media.

Figure 7. left to right: an example of hatching, cross-hatching, and feathering in pastel. Photo credits to Richard McKinley.

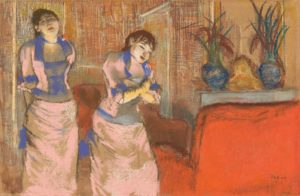

Degas used pastel in order to capture a sense of movement among his subjects and to create a sense of immediacy, emphasizing its suitability for capturing fleeting scenes of modern-day Parisian experiences. Degas’s pastel technique was idiosyncratic. He often applied pastel to an unprepared canvas or sheet of paper, then sprayed boiling water over the surface to make the pastel into a paste, thus creating a variety of textures.[32] His method of application appeared quick, chaotic and raw, although his frequent use of cross-hatching indicates a certain systematic quality to his approach (Fig. 7). Degas’s pastels were also heavily sealed, often with casein, a protein found in milk, to protect the powdery, fragile medium.[33] Layering pastels on top of monotype prints allowed him to replicate the way in which light manipulated the color of objects and figures on and off stage in his many images of the ballet and of Parisian café life.[34] For example, this technique can be seen in Two Women (1878-1880; Fig. 8), an image of cabaret performers. In the face of the woman on the left, Degas layered colors such as yellow, blue, and pink, heightening the complex, colored shadows associated with the Impressionist style. Both women’s faces are also bathed in a bright white that suggests the strong, harsh glow of indoor lighting. The directional strokes that comprise the skirts of the two women also convey the ephemeral creases that appeared in the fabric as they moved.[35]

Figure 8. Edgar Degas. Two Women. 1878-1880. Pastel over watercolor and charcoal over tan laid paper, mounted to board. 29.21 x 44.45 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., United States.

During the 1880s, the revival of pastel by figures such as Millet and Degas was bolstered by a broader revival of interest in the Rococo style. This “rediscovery” of the Rococo in the 1880s depended in large measure on developments that had begun two decades earlier. In the 1860s, the Louvre Museum received a large donation from Louis La Caze and François Walferdin of Rococo-era fêtes galantes by artists such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Jean-Antoine Watteau.[36] These works were given their own gallery space specifically for this theme.[37] Around the same time, Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie used their patronage to encourage a revitalization of the Rococo, especially in portraits of Eugénie by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.[38] Portrait of Empress Eugénie (1857; Fig 9), for example, harkens back to the Rococo through the pastoral background and extravagant dress: these aspects harken back to precedents such as Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s famous Marie Antoinette en Chemise (1783; Fig 10).

Figure 9. Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Portrait of Empress Eugénie. 1857. Oil on canvas. 138.4 cm x 109.2 cm. Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Washington D.C., United States.

The government of the Third Republic also played an important part in this development: beginning in the 1890s, the arts administration began a series of restoration projects that claimed Rococo art and craft as an important part of the French national patrimony.[39] This interest was sparked by Edmond and Jules Goncourt, whose Salon gatherings in their home and art criticism initiated greater interest in eighteenth-century applied arts. In the 1890s, items of furniture rescued from renovations of various eighteenth-century Parisian hôtels that were converted to national administration buildings were given to the Louvre to serve an artistic testament of the nation.[40] These elegant Rococo furnishings and art objects inspired artisans who adapted the style of these crafts into the burgeoning Art Nouveau style, above all in the sinuous arabesque curves that defined this aesthetic.[41]

Figure 10. Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Marie Antoinette en Chemise. 1783. Oil on canvas. 89.8 x 72 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York, United States.

Henri d’Orléans, The Duc d’Aumale, also contributed to the revitalization of the Rococothrough his restoration of the Château de Chantilly, estate of The Duc d’Aumale, a project that lasted from 1872 to 1884. His involvement in this prominent restoration project won him election to the French Academy in 1873 and to the Academy of Beaux-Arts in 1880.[42] The Duc held salons for the literary and artistic elite in the petit chateau, the Hunt Gallery. These guests were able to view Rococo works such as pieces by Charles-André van Loo, Jean-Antoine Watteau, portraits of Louis XV, and portraits of Madame de Pompadour that were above rows of bookcases filled with scholarly works by representatives of the Rococo.[43] The Hunt Gallery Rococo interior allowed him to publicize his association with the Central Union of the Decorative Arts, an organization created to promote the applied arts that became an important vehicle for the Rococo revival: the Duc served on the consulting committees for the Union’s Paris exhibitions.[44] The erudite members of the Central Union of the Decorative Arts strongly advocated for the reclamation of art from the Rococo period by the nation’s cultural institutions.[45] All of these developments made pastel, a medium intimately connected to the Rococo, fertile ground for further experimentation and adaptation.

26. Debora Silverman, “The Third Republic and the Rococo as National Patrimony” In Art Nouveau in Fin de Siècle France: Politics, Psychology and Style (Oakland: University of California Press, 1989), 142.

27. Paul Tucker, “The First Impressionist Exhibition and Monet’s Impression, Sunrise: A Tale of Timing, Commerce, and Patriotism.” Art history 7, no. 4 (1984): 465.

28. Richard Kendall, “The Metaphor of Craft: Tradition, Draughtmanship, and the Transformation of Degas’s Technique” In Beyond Impressionism (London: National Gallery Publications, 1996), 59.

29. “Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty,” What’s On, Museum of Modern Art, last modified 2016, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1613

30. Laura Anne Kalba, “Impressionism’s Chemical Aesthetic: The Materials and Meanings of Color” In Color in the Age of Impressionism: Commerce, Technology, Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2017), 81.

31. Kalba, 81.

32. Alfred Werner, Degas: Pastels, (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1998), 16.

33. Werner, 16.

34. Kalba, 91.

35. Kimberly Schenck, “An Experiment in Pastel and Watercolor by Degas,” National Gallery of Art Blog, National Gallery of Art, November 17, 2020. https://www.nga.gov/blog/pastel-watercolor-degas.html

36. Silverman, 153.

37. Silverman, 153.

38. Silverman, 153.

39 Silverman, 142.

40. Silverman, 155.

41. Silverman, 158.

42. Silverman, 146.

43. Silverman, 146.

44. Silverman, 147.

45. Silverman, 142.