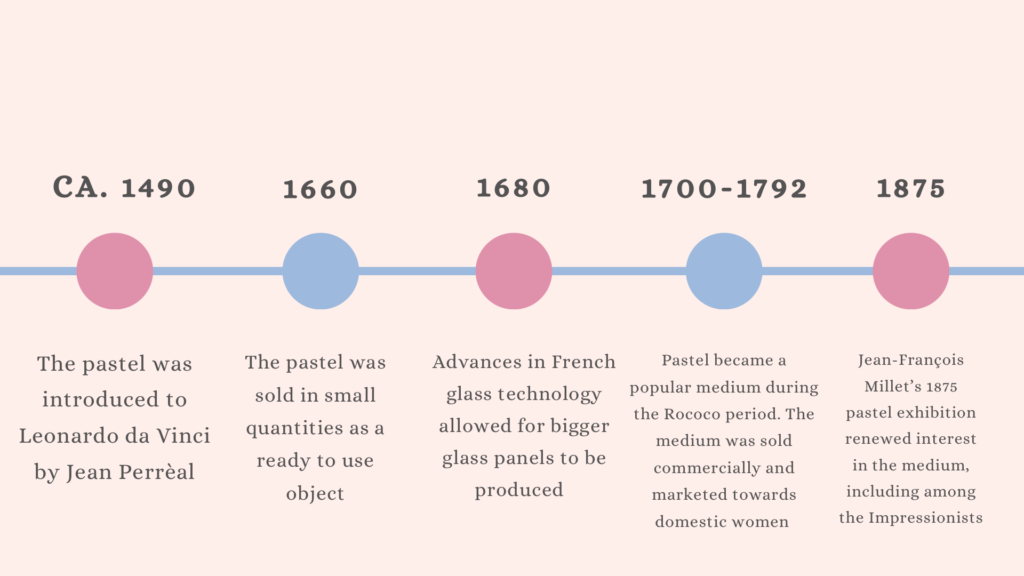

In order to understand how and why Gonzalès turned to pastel for her Salon debut and beyond, it is necessary to know more about the history of the medium and the vicissitudes of its reception. Gonzalès chose pastel in part because of its longstanding association with three interrelated phenomena: the art of the Rococo period; color and its sensory appeal; and the domain of the “feminine.” These associations allowed Gonzalès to frame her entry into the Parisian art world as a professional woman artist in safely acceptable terms.

Pastel is composed of three separate ingredients: colored pigment, filler, and binder. Combinations of colored pigments, the same raw material as oil paint, can be used to create brighter or more muted colors. Filler is a white mineral or powder, such as talc, that controls the shade of the crayon, with more or less filler added to create a lighter or darker shade. Binder consists of a sticky or oily ingredient, such as an oil or a type of natural gum. The more binder added, the more wet or oily it looks when applied to a surface.

The pastel technique has its origins in Renaissance France. “The manner of dry coloring,” according to Geneviéve Monnier, was introduced by Jean Perrèal to Leonardo da Vinci at the turn of the sixteenth century, when Perrèal made a trip to Milan with Louis XII.[9] In the 1500s and 1600s, pastel was used primarily for preparatory sketches, not as a medium to produce finished pictures. Before the 1660s, many artists manufactured their own crayons, as commercial manufacturing production was very limited, and the quality of the product was often poor.[10] However, in the late seventeenth century, several innovations allowed pastel to be used for high-quality finished artworks. In the 1680s, a glass pouring technique developed by the French royal glassworks manufactory allowed for the production of plates big enough to cover large-scale portraits. Such surface protection was essential for the preservation of works in pastel.[11]

Accordingly, by the early 1700s, the popularity of pastel as a medium began to grow. Due to improved production technology, economic appeal, a revival of craft, and an increased demand for portraits, a rapid increase in trade of the medium occurred.[12] The task of fabricating pastel often fell into the hands of independent artisans, who worked closely with pastel artists to create their desired product in terms of color and consistency.[13] In the early eighteenth century, the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts and the Académie des Sciences increasingly emphasized the importance and value of craft practices.[14] In addition, artists started to favor pastel because they could complete portraits more quickly than with oil paint due to the lack of drying time needed and the ease of transportation. Moreover, pastel portraits were a relatively inexpensive item and possessed a higher production yield, which further widened their appeal.

As pastel gained popularity and greater critical esteem in the 18th century, it also accrued a certain association with the feminine. Firstly, this derived from the medium’s association with color, which in turn, was perceived as feminine due to its links with emotion and the senses.[15] By contrast, line was associated with logic, which was viewed as an inherently masculine trait.[16] This art-theoretical debate was addressed in Charles Le Brun’s essay “Thoughts on M. Blanchard’s Discourse on the Merits of Color” (1672). Le Brun, a partisan of line, refuted Louis-Gabriel Blanchard’s claim that color was superior to design because it differentiated painting from all other imitative arts. Le Brun argued that design is both “intellectual and practical” and “utterly necessary for coloring,” because line can “even express the passions of the soul without the need for colour except for showing blushing and pallor.”[17] Le Brun’s terminology is crucial: by linking color with the action of blushing, he invoked both a physiological reaction stereotypically related to female propriety, and the fetishized terrain of a woman’s skin. This influential text led later theorists, philosophers, and artists to cement this negative association between color and femininity. Immanuel Kant, in his 1790 Critique of the Power of Judgement, repeated the essence of Le Brun’s stance when he declared that color and texture were superfluous—i.e., superficial—and masked the truth of essential forms.[18] Anthony Pasquin, an eighteenth-century art critic, similarly dismissed pastel as “chiefly calculated for the observance of those whose love of softness and finery govern their applause and protection,” a clear reference to female connoisseurs.[19] These gendered views left a long lasting imprint: pastel was thereafter relegated to the bottom of the hierarchy of media established by the Académie.

Pastel was also deemed more appropriate for women artists, relative to oil painting, in part because it was seen as cleaner to work with. Beginning in the late 1700s and early 1800s, pastels created by commercial entities were marketed to women: advertisements claimed that pastel boxes offered a range of colors ideal for “flowers, figures, and landscapes.”[20] These genres were deemed suitable for women because these subjects could be easily copied, and did not require academic training in the study of history paintings and the nude male form, which women only infrequently were allowed.[21] While its wide accessibility and ease of use encouraged women to take up pastel, its associations with the feminine tainted the medium’s reputation in the eyes of academicians and many critics. It became known as a domestic pastime; or, as an anonymous treatise of 1788 stated, a “rescue to so many young women from the tedium of solitude.”[22] Pastel was considered a “resource[e] against idleness, the source of so many indiscretions.”[23] The medium, therefore, was perceived as a tool to keep women occupied and thereby to bar any immoral thoughts or deeds. This made pastel a double-edged sword for women practitioners. If a woman created pastel art, her work was deemed as amateur and done for mere amusement, yet this was the only medium readily accessible to her. This double bind contributed to a larger set of systematic barriers that made it difficult for women to claim the identity of a professional artist.

Figure 5. Jean-Francois Millet. Shepherdess and Her Flock. 1864-1865. Black Chalk and Pastel. 36.4 x 47.5 cm. Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, United States.

But, after a long period of disapprobation, pastel was revived in the nineteenth century, and was accompanied by a shift in the ways artists and audiences perceived the medium and its characteristic aesthetic. At the time of Jean-François Millet’s death in 1875, a posthumous exhibition and auction of his pastel works, then owned by Emile Gavet, sparked a resurgence of the medium: it was revalued as suitable for completed, exhibition-worthy pictures. The exhibition and public auction of Millet’s works enjoyed great critical and commercial success.[24] It must be noted, though, that Millet’s use of pastel differed substantially from that of eighteenth-century practitioners. He exchanged the refined blending and smooth, velvety textures of the Rococo era for chaotic cross hatching and heavy contours.[25] These techniques can be seen in Millet’s Shepherdess and Her Flock (1864-1865; Fig. 5): the artist used complex, multi-directional and multi-colored strokes to depict elements such as the grass; the sun’s rays cutting through the clouds; and the coat of the shepherdess, outlined with strong, thick contours. While the revival of pastel cannot be solely contributed to this exhibition and auction alone, Millet showed how pastel could be reformulated to fit a late nineteenth-century aesthetic.

9. Geneviéve Monnier, “Pastel,” In Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2003. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000065711

10. Marjorie Shelley, “Painting in the Dry Manner: The Flourishing of the Pastel in 18th Century Europe,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 68, no. 4 (2011): 5.

11. Shelley, 8.

12. Shelley, 5.

13. Shelley, 8.

14. Shelley, 8.

15. Melissa Hyde, “The Makeup of the Marquise,” In Making Up the Rococo: François Boucher and His Critics (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2006), 107.

16. Jacqueline Lichtenstein, “Making up Representation: The Risk of Femininity”, Representation, no. 20 (Autumn 1987): 81.

17. Charles Le Brun, “Thoughts on M. Blanchard’s Discourse on the Merits of Colour” (1672), reprinted in Charles Harrison, Paul Wood and Jason Gaiger, eds., Art in Theory 1648-1815: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2000), 183.

18. Ruth Kenny, “The Craze for Pastel”, BP Spotlight: The Craze for Pastel (blog), The Tate, 2014, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/display/bp-spotlight-craze-pastel/essay.

19. Kenny, “The Craze for Pastel”, n.p.

20.Stacey Sell, The Touch of Color: Pastels at the National Gallery of Art, (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2019), 7. https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/exhibitions/pdfs/2019/touch-of-color-pastels.pdf

21. Sell, 7.

22. Sell, 7.

23. Sell, 7.

24. “Peasants in Pastel: Jean-Francois and the Pastel Revival.” Gallery Text, J. Paul Getty Museum, last modified 2019, http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/millet_pastels/downloads/pastels_gallery_text.pdf

25. Sell, 7.