What is Originality?: How Dice Can Explain the Theory of Multiple Discovery

Katie Carroll

Introduction

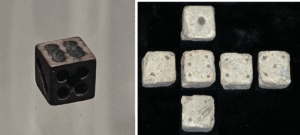

The concept of dice has been around long before recorded history (Hovanetz, 2023), having been used in many different games played throughout time. Today, the whole world uses the same design of dice, but this was also true thousands of years ago. Different cultures and empires around the whole who did not have contact with each other still used the same designs for dice. Figure 1 (shown below) shows a six-sided die from Ancient China (Straub, 2024) looking very similar to figure 2, a die from Ancient Rome (Scott, 2024). They are both cubes small enough to fit multiple in the palm of one’s hand, and have pips, or the dots on the dice, in the same arrangements. The pips are made the same way too: instead of being drawn on after the dice has been made, they are indented into the dice.

Fig. 1, from the Jiangyin Museum Fig. 2, from Leicestershire, England

Why do these cultures have near-identical designs of dice made at the same time independently of each other (Lubowitz et al., 2018). Different cultures around the world needed a way to randomize an outcome, which led them both to discovering dice and the best way to make them. But this begs the question: Who can be credited with the invention of dice? Who “owns” that idea? Was dice an idea that was invented by humans, or was it a geometric concept that was just waiting to be discovered? The invention can be used to discuss the theory of multiple discovery and what originality of invention truly means.

Multiple Discovery in Math and Science

Multiple discovery doesn’t just happen with dice: it can be seen in math too. Researcher Robin W. Whitty from Queen Mary University of London notes how this is extremely common in math in their paper “Some Components on the Study of Mathematics,” (2017). In one example, discuss how the “Little Theorem,” whose invention is credited to Joseph Wedderburn, was actually proved slightly earlier (and in Whitty’s opinion, slightly better) by Leonard Dickson (Whitty, 2017). Yet, “there is no move to re-brand it Dickson–Wedderburn” (Whitty, 2017). A similar incident happened with the Prime Number Theorem between mathematicians Alte Selberg and Paul Erdős, although in the end they shared the credit of discovering the theorem. (Whitty, 2017). Many mathematical theorems are named after the person who invented them, yet it always seems to be a race as to who discovered it first, because they get the fame that goes along with it. But Multiple Discovery is so common in math that it can be extremely difficult, if near impossible, to pin-point the true original creator. This is extremely similar to the invention of dice. Online Encyclopedia Britannica credits dice to be from Ancient Greece (Glimne, 2024), while ExcelinEd, an organization aiming to spread education opportunities for children, credits dice to be from the Indus River Valley (Hovanetz, 2023). It is impossible to credit their true origins back to any one person or culture because they were discovered at the same time.

Researchers Nicole C. Nelson, Julie Chung, Kelsey Ichikawa, and Momin M. Malik (2022) would agree with Whitty (2017), showing how Multiple Discovery exists in psychology. Led by Associate Professor Nicole C. Nelson from the Department of Medical History and Bioethics at the University of Wisconsin, their research paper focuses on the replication crisis and how it was discovered through Multiple Discovery (2022). The replication crisis is when published research results cannot be replicated, thus questioning the validity of the results.Nelson et al.’s research shows how many different researchers around the world stumbled across the replication theory at the same time (2022), very similar to how Whitty describes different mathematicians discovering different theories at the same time (2017). However, unlike Whitty’s article, Nelson et al. does not discuss the consequences or complications of the Multiple Discovery Theory, only that it played a part in discovering the replication crisis. Even still, these two sources support the idea that Multiple Discovery has been deeply rooted in science and math for many years.

Originality & Inspiration

Nelson et al.’s article also mentions how little research there has been done on the Multiple Discovery Theory (2022). They mainly mention research dated back to 1961, from an American sociologist Robert Merton, as the most relevant to the case. Nelson et al.’s research was published in 2022, highlighting the time gap between relevant sources—more research is needed to be done on the theory of Multiple Discovery.

Merton believes that Multiple Discovery happens because of religious, economic, or societal factors that push scientists to study similar areas at the same time, making Multiple Discovery more likely (Nelson et al., 2022). This is similar to Whitty’s 2017 article about Multiple Discovery in math. The study of mathematics builds on itself, and one cannot discover the complex equations without understanding the basics. When all mathematicians have the same knowledge of all the previous theorems invented, it produces the scenario that Merton describes, making Multiple Discovery much more likely. But because ideas are being formed the same way, does that make them original? If the same inspiration is occurring to different scientists and mathematicians, does it happen in other fields too?

Published in The Atlantic, the article titled “Who Owns an Idea?” by Boris Kachka (2024), an author and senior editor at The Atlantic, discusses the originality of ideas in books and media. They discuss the more modern plagiarism side of things, but also whether ideas can be “owned” by one person—similar to what is discussed in Nelson et al.’s and Whitty’s articles. Kachka uses the example of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath, and how it was written with the help and notes of Sanora Babb (Kachka, 2024), but she remains largely uncredited. When she published her own novel many years later, her work was seen as “unoriginal” and having been “already done before,” even though the “original” work critics were referencing was actually her own. Kachka notes how “you can’t copyright an idea” (2024), so how can one really tell where an idea originated? Nelson et al. seems to offer an answer to this question through Robert Merton’s work. It was similar stakes and information at the time that pushed both Steinbeck and Babb to write about the Dust Bowl, yet wrongful circumstances lead Steinbeck to retain all the credit.

Ethics

This leads to the ethics behind Multiple Discovery, partly discussed by Kachka. They discuss how Multiple Discovery could lead to accusations of plagiarism (2024), especially modern-day. “Multiple people can independently imagine the same scenario,” Kachka writes (2024). So, it’s only a matter of time as to who publishes that idea first. This is what makes the true discovery or invention of something so difficult: we must rely on records. This is perhaps why the creation of dice could be credited to so many different places around the world. It’s less of a race of “Who thought of this first?” but more so of “Who wrote this down first?”

In the editorial “Two of a Kind: Multiple Discovery AKA Simultaneous Invention is the Rule” by Editor-in-Chief James H. Lubowitz and Assistant Editors-In-Chief Jefferson C. Brand and Michael J. Rossi of Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, they discuss the theory of Multiple Discovery from an editor’s perspective. Lubowitz et al. uses the example of two research groups submitting similar articles at the same time to explain the theory (2018). It also connects to Kachka’s idea (2024) that it’s a race to write things down first. Even though one group might have started research first, if another group publishes an article before them, they get the credit (Lubowitz, 2018). However, Lubowitz et al. mentions how they try to combine similar articles together in joint-publications, crediting the idea to both of them. However, there are times when the researchers get angry about this, because they claim their own research is superior and unique to the article they are being paired with (2018). Lubowitz et al. says that as editors, they are not familiar with every single scientific nuance, so these conflicts are created by accident. There are many parties at stake when Multiple Discovery happens—the authors, the editors, and the general public.

Conclusion

People yearn to know who invented something: they want one singular person, place, or organization to credit. But, it’s not always that simple. The convoluted invention of dice shows the theory of Multiple Discovery at play: multiple people and cultures invented an idea at a similar time, because of the current societal factors pushing that discovery. The same happens with many other math and science concepts, questioning how original ideas are. It is hard to determine exactly who can be credited for an idea, leading to the ethics of invention and claiming ideas. The question of “Who owns an idea?” cannot be answered with a single name, it is instead a body of many factors combined.

References

Glimne, D. (2024, April 11). dice. Encyclopedia Britannica.https://www.britannica.com/topic/dice.

Hovanetz, C. (2023, December 4). Math Monday: Dice. ExcelinEd. excelined.org/2023/12/04/math-monday-dice/.

Kachka, B. (2024, October 18). Who Owns an Idea? The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2024/10/who-owns-an-idea/680299/

Lubowitz, J. H., Brand, J. C., Rossi, M. J. (2018, August). Two of a Kind: Multiple Discovery AKA Simultaneous Invention is the Rule. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 34(8), 2257-2258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2018.06.027.

Nelson, N. C., Chung, J., Ichikawa, K., Malik, M. M. (2022). Psychology Exceptionalism and the Multiple Discovery of the Replication Crisis. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 184–198. DOI: 10.1177/10892680211046508.

Scott, W. (2024, June 30). 9BFE00; roman lead dice [Photograph]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:9BFE00_-roman_lead_die_(FindID_103936).jpg, Leicestershire, England.

Straub, D. (2024, June 8). Chinese dice from Late Yuan Dynasty to early Qing Dynasty [Photograph]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chinese_dice_from_Late_Yuan_Dynasty_to_early_Qing_Dynasty.jpg, Jiangyin Museum, Jiangyin City, China.

Whitty, R. W. (2017, January). Some Comments on Multiple Discovery in Mathematics. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 7(1), 172-188. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.201701.14.