A cavern on 16th Street: How does the removal of public artistic expression affect national consciousness of experiences?

Stella Keskey

What comes to mind when thinking about cities like Washington D.C. and New York City? Endless traffic and crowds of tourists aside, I picture the vibrant art that is seemingly everywhere. Whether it be on the streets or the sides of buildings, tags, murals and painted messages decorate these cities. And upon taking a closer look, one can learn about the rich history and experiences of the natives and residents of these areas. In June 2020, two blocks of 16th street in Washington D.C. were painted with the phrase “Black Lives Matter” to memorialize the Black Lives Matter movement and the reverberation of the movement felt across the capital and country (Archie). The original intention of this mural, according to the D.C. mayor, Muriel Bowser, was to permanently “commemorate the protests” (Archie). Recently, these intentions have been undermined at the order of a bill initiated by Representative Andrew Clyde (R-GA). The mural has since been removed (Archie). The removal of street art in urban spaces pertaining to social justice such as the “Black Lives Matter” mural impacts the identity and memory of marginalized communities and events, ultimately devaluing their importance from the national consciousness of current and future generations.

Decorating the walls and spaces that surround us is not a new phenomenon. As humans, we have been documenting our experiences, thoughts and creativity since ancient times. Take the famous cave paintings of Lascaux France for example. Discovered in 1940, these cave walls are over twenty-one thousand years old and contain six hundred eighty frescoes (paint applied to wet plaster, creating a durable and resilient piece of artwork (Wikipedia Contributors)) and one thousand five hundred engravings (“Lascaux”). More locally to the United States, take Native American art for another example. A recent Smithsonian exhibit displayed artwork created by Plains tribes to document their experiences, paired with descendants’ modern interpretations of these near ancient pieces.

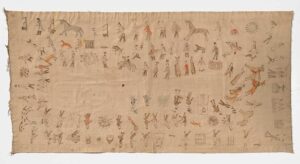

“Long Soldier Winter Count.”

Above is a piece titled “Long Soldier Winter Count.” Spanning from 1798 to 1902, each symbol depicts an event that a Plains community felt represented the year as a whole. This piece has been passed from generation to generation so as to finish the winter count. By connecting past and present, this seemingly subdued piece alone preserves cultural identity for Plains descendants in the process (Shows). As a general public in the United States, much of what we understand about ancient generations such as the Lascaux civilization and Native American tribes and their experiences is through the discovery of the visually immersive artifacts they have left behind. More importantly we have realized that the depictions of events written by the “conquerors” vastly differs from “conquered” through pictorial storytelling. The Native Americans’ genuine experiences, outside of imperialist context, is seen in these multi-generational pieces, offering a perspective of the real story. Given that much of Native American life has been destroyed in the process of colonial displacement, preserving and celebrating these discoveries is especially important for Native descendants and their identity.

As a society, our memories and understanding of past events and their effects is highly dependent on the narratives presented to us. According to Antonella Pocecco in her book Collective Memory Narratives in Contemporary Culture, “the relevance and selection of events, the organization of connections and cross-references between past, present, and future, as well as the importance of diversified collective imaginaries are the keys to narrative constructions of memory that prove to be sensitive and decisive for its continuity and its intergenerational transmission” (Antonella Pocecco et al.). In reference to how memories are formed and transferred among peoples and generations, Pocecco communicates that our collective perceptions are highly vulnerable to public depictions of historical events. This is super interesting, especially in regards to the historical figures chosen to be concretely celebrated in statue form. In fact, Pocecco argues that commemorating figures “de-contextualiz[es]” events and risks separating these figures from their “historical reality” (Antonella Pocecco et al.). Thus, given that “memory is a powerful political tool,” this creates a “transfigured’ memory” (Antonella Pocecco et al.), which has the potential to be highly controversial. We are constantly receiving information that forms our collective memory. When the narratives presented are incongruent with reality, our collective memories and understandings of historical events morph according to what is being publicly celebrated.

Our memories are also shaped in response to physical art in public spaces. Twelve authors concerned with geographical research discuss art and memory in their article, “Editorial Introduction: Geography and collective memories through art.” Upon visiting previously colonized countries such as Colombia and Australia, these authors found that “memory becomes material through public art and arts practices” (Castro et al.), ultimately demonstrating the “possibilities of creative work to give expression to different histories, subjectivities and experiences which challenge” previous geographic understandings (Castro et al.). In other words, art in communal spaces created by locals offers another perspective. Similar to the creations of Native Americans that have been preserved, the experience of Colombian women for example is vulnerably communicated through massive works seen below.

“Embroideries of Memory”

“Embroideries of Memory” is known to be an offering of “truth-telling” regarding Colombian women’s experiences of being forcibly removed by armed conflict in the country (Castro et al.). This massive fabric banner acts as a force of resistance against government denial of displacement in ongoing violent times, by forcing itself into the public’s minds, and therefore memory (Castro et al.). Thus, community members are able to connect to their identity and how the culture/identity they identify with is represented by public street art. “Embroideries of Memory” is a positive example of uplifting the voices that have been silenced, hopefully forging a concrete impression of Colombian women’s adverse experience in the memories of current and future generations. To remove the testament to what women must undergo is to effectively harm national awareness. Presently, there is no other public documentation or recognition that these women are being displaced. Without physical evidence, these terrible experiences never happened according to public memory, and therefore no steps will be taken to improve these conditions.

Publicly displayed art is a culturally connective tissue, institutionally approved or not. In New York city, arguably most of the art that decorates the streets is labeled as graffiti, rejected and removed. In an effort to celebrate the institutionally rejected expressions of urban communities, Jeffrey Deitch organized a series of works and accounts in his book, Art in the Streets. Deitch prefaces that street art has been historically labeled “unsanctioned interventionist practices” that are to be “widely regarded by the general public as a kind of urban noise – prosecuted when possible, but otherwise best ignored” (Deitch et al.). In this quote the author points to the negative connotations that circulate the word graffiti, and how simply assigning the word “graffiti” to these massive works devalues the time, energy and creativity that went into beautifying and documenting personal experiences. However, upon genuine investigation, one realizes that with art “there is a long lineage of political statements, protests, and advocacies made on the streets” (Deitch et al.). Deitch shines light on the ability of residents to document a sort of “other history” (Deitch et al.) on the walls around them for others to see and understand through deeply vulnerable murals. The anonymity of graffiti provides space for artists to make political statements about personal experience or otherwise without having to hear direct responses from peers.

“Energy from My Soul”

This piece is titled “Energy from My Soul,” and was painted on the side of a subway car on 180th Street Station, Bronx, New York, 1980. The writing on the side of the train car reads “There once was a time when the Lexington was a beautiful line, when children of the ghetto expressed with art, not with crime. But then as evoultion past, the transit’s buffing did its blast. And now the trains look like rusted trash. Now we wonder if graffiti will EVER LAST…” (Unknown, Deitch et al.). The poem written on the side of this unused subway car reflects the attitudes of people living in the “ghettoes” of New York City at the time. Their experiences are something I never would have read in a history book. If I did, it would have been two mere sentences that could not encompass the struggle and emotion that is communicated through capital letters, bright oranges and yellows, the fiery emotion gathered from the visual experience. To remove works like these is to once again bury the circumstances people, especially marginalized communities, must endure.

Bringing the conversation back around to street art that was once institutionally approved of, I visited 16th Street in D.C. On Monday March 24th at around 4:45 pm, I arrived at the torn up, blocked off site of the recently removed “Black Lives Matter” street mural. The on and off drizzle of the day had finally come to a complete end, and the only traces that remained were the light grey sky and the damp pavement of 16th Street. When I was about one hundred feet from the scene of the crime I realized what I was about to experience. I thought to myself, “wow, this is about to be depressing.” And there it was. A 5 inch deep cavern lies in the plaza with sediments of black and yellow. The only indication that there was once something of social and historical importance in the BLM Plaza (soon to be renamed the Liberty Plaza).

For the D.C. Mayor to attempt to immortalize the mural in 2021 was radical. The experiences of black Americans and adversity forced upon people of color has historically been silenced or documented so as to remove the blame placed on the oppressor. The Black Lives Matter movement is something that cannot be tampered with in the memories of our generation. What I worry about is future generations. How will they really know the sorrow and tenacity of our generation when our cave walls are blank?

Future generations will have to at some point study the events that are current to us. But if they are still reading history books, how will that impact their grasp on events like the protests of the Summer of 2020? Studies have shown that “the issue within social studies and engagement tend to stem from the area that students feel disconnected from the material and therefore, have no incentive to engage with or learn from it” (Episcopo). Here, the studies reference the usual method of teaching history – textbooks, which do not encourage student engagement given that the events feel distant and cold. Students are destined to be simply uninterested in the events that currently plague our minds and lives. Instead, researchers recommend a “multi-modal” learning approach so as to promote interest and historical empathy (Episcopo). This can be done by offering anecdotal evidence, visual aids or experiential learning (Episcopo), which fosters an environment for students to “consider the perspectives of and connect with people in the past” (Episcopo). In other words, reading about history does not provide the genuine understanding or further curiosity that other methods do. Especially if this history is solely what is approved of institutionally, and ignores the experiences of the rest of current events that are our true reality.

Indeed, there is no life or emotion in textbooks like there is in art. And in order for future generations to accurately understand the history of their own country and current generations to have valuable connections to their own identities, we need physical artifacts. The most emotionally involved, in my perspective, being the beautifully visceral street art mentioned earlier, we must preserve and encourage creative expression in our streets.

Works Cited

Antonella Pocecco, et al. Collective Memory Narratives in Contemporary Culture. Springer Nature, 2023.

Archie, Ayana. “City Crews Have Begun Painting over the ‘Black Lives Matter’ Street Mural in D.C.” NPR, 10 Mar. 2025, www.npr.org/2025/03/10/nx-s1-5323911/black-lives-matter-mural-washington-dc.

Castro, Laura Rodriguez, et al. “Editorial Introduction: Geography and Collective Memories through Art.” Australian Geographer, May 2022, pp. 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2022.2052556.

Deitch, Jeffrey, et al. Art in the Streets : [… Presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, 17 April – 8 August 2011, and at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, 30 March – 8 July 2012]. Skira Rizzoli, 2011.

Episcopo, Andrew R. “How the Medium of the P How the Medium of the Portrayal of a Historical Event Affects Students’ Perception of the Event.” St. John Fisher University, May 2013.

“Fresco.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Mar. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fresco.

“Lascaux.” Archeologie.culture.gouv.fr, archeologie.culture.gouv.fr/lascaux/en.

Shows, Art. “Stories Unbound: Exhibition of Narrative Art Shows More than a Century of Native Life on the Plains | NMAI Magazine.” NMAI Magazine, 2024, www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/Unbound-Exhibition-narrative-art-Plains.