The Liberation of Public Spaces: Street Art’s Brush with So-Called Democracy

Hanan Nathan-Slarskey

Vandal. Hoodlum. Defacer. Ruffian. Graffiti artist. To many unfamiliar with the diverse spectrum of graffiti, the term “graffiti artist” evokes images of a clandestine figure, likely a young man, skulking through neglected urban landscapes under the cover of night, armed with spray paint and a penchant for defacing concrete structures. This could not be further from the truth.

The origins of street art are shrouded in mystery, much like the artists who bring it to life. Historians trace its beginnings back to ancient times, with evidence of graffiti dating as far back as the 1st century B.C.E. in Rome, where citizens left messages etched into dry brick walls. As Kelly Wall, an artist and professor at the Otis College of Art and Design, implies in her video for TEDEd, street art was not always a subversive act: “In Pompeii, ordinary citizens regularly marked public walls with magic spells, prose about unrequited love, campaign slogans, and even messages to champion their favorite gladiators” (Wall 0:57). It wasn’t until the French Revolution that graffiti began to take on its modern connotations of rebellion and protest. During this time, members of the proletariat defaced prestigious artworks to challenge the entrenched social hierarchy. Angered elites proclaimed this act “vandalism,” with regards to the ancient Germanic tribe who famously sacked Rome (Wall 1:32). This categorization is ironic, given the Roman walls these ancient Vandals ruined, or “vandalized,” were more than likely already covered by ancient graffiti.

Since then, street art has evolved into a powerful form of expression that often parallels periods of political upheaval. Accomplished geographer Tim Unwin, UNESCO chair in ICT for development and Emeritus Professor of Geography at the University of London asserts that, “The idea that space is socially produced, or constructed, has become one of the foundations of contemporary social and cultural geography” (Unwin 11). In a democratic system, governments have an obligation to create spaces that reflect the interests of its citizens. When citizens find themselves at odds with these spaces, it is justifiable that they reclaim, and therefore democratize that space for themselves.

One of the most enduring examples of political street art can be found in the graffiti that adorned the Berlin Wall during the Cold War. Here, the wall served as a tangible battleground for the clash between freedom of expression and totalitarianism (Wall 2:57). On one side, vibrant images of love and desire blossomed, in stark contrast with the grey, silent facade of oppression on the other. More recently, the tragic murder of George Floyd and other members of the Black community, caused cities across the nation to erupt in protests, igniting a powerful wave of momentum for the Black Lives Matter movement. In conjunction, activists turned to street art as a potent tool for mobilization, harnessing its expressive power to galvanize communities and reclaim narratives that have been systematically suppressed. Their art serves as a defiant challenge to the insidious systems of white supremacy that have long plagued our society. Despite being labeled illegal under the pretext of vandalism, their creations defy attempts to silence their voices, asserting their right to reclaim public spaces and reshape the collective consciousness.

Street art and graffiti serve as dynamic cultural expressions that are intertwined with the experiences and identities of lower-class communities. More often than not, these communities are underserved and ignored by the democratic government theoretically designed to help them. In Washington D.C., the urban canvas of U-Street not only reflects the socio-economic struggles, aspirations, and narratives of marginalized individuals but also embodies a unique form of creative resistance. When Black folks in D.C. were systematically disenfranchised and forced out of their homes through eminent domain and gentrification, street artists took it upon themselves to beautify and democratize their public spaces. What the government ignored and devalued, became a public, community informed tapestry of visual art and writing.

Learning about underserved, underappreciated areas is paramount if we are to preserve communities and prevent further oppressive effects of gentrification. While there is growing recognition of the importance and mutual beneficence brought about by community-based learning, the full extent of its possibilities remains largely unexplored. In a world where marginalized voices are often silenced and public spaces are increasingly commodified, street art emerges as a formidable form of creative resistance. Through the lens of street art, students can explore the complexities of societal power dynamics and challenge dominant narratives. Integrating street art into community-based learning curricula is not only essential for preserving cultural heritage and fostering civic engagement but also crucial for empowering marginalized communities to assert their narratives and identities in the face of gentrification and systemic inequality.

From Walls to Galleries

During the 1970s, graffiti artists in America organized into unions, marking a significant moment of collective empowerment. Wall expounds that wealthy patrons responded by strategically selecting certain graffiti artists to elevate, effectively co-opting the movement and integrating it into the realm of high-end art (Wall 3:17). In this curated space, street art became commodified, valued primarily for its profit potential rather than its cultural significance. The consequences of this co-optation were profound. Internal strife and resentment corroded the once-unified unions, ultimately leading to their decline. Unfortunately, this system has endured, perpetuating the exclusion of radical artists from mainstream art institutions and the lucrative art market. Recent data from a 2021 study by Data USA sheds light on the stark disparities within the art world. An overwhelming majority—84.5%—of those employed in roles such as archivists, curators, and museum technicians are White (Data USA 9). These figures underscore the elitism and exclusionary practices that continue to define the high-brow art world, serving as another manifestation of systemic discrimination against those who do not conform to dominant cultural norms.

Street artists stand in stark contrast to the wealthy elite. Typically hailing from marginalized backgrounds, street artists are more likely to be low-income, people of color, female, or members of the LGBTQIA+ community. Whether these demographics were shaped by the inherent diversity of street artists from the outset or were a response to exclusion from the high-end art world is a chicken-and-egg situation. Nevertheless, the fact that minorities continue to be sidelined in mainstream art circles perpetuates the diverse makeup of street artists. In this light, street art emerges as a vital counterbalance to the elitist, hyper-capitalist landscape of traditional art institutions. By providing a platform for marginalized voices and identities, street art challenges the hegemony of the elite art world and its stifling effects on creativity and individual expression. Thus, the mere act of creating street art can be viewed as a form of resistance against the hierarchical structures of the high-end art establishment.

Opponents of public street art often insist that artists should confine their creative endeavors to “legal” venues. In their article “Graffiti Hurts and the Eradication of Alternative Landscape Expression,” Terri Moreau, Professor of Geography at Park University, and Derek Alderman, Professor of Geography at East Carolina University, describe examples of how this manifests. For instance, Keep America Beautiful, a prominent non-profit organization backed by corporate giants like H&M, PepsiCo, and McDonald’s, launched the Graffiti Hurts program in 2007. This initiative provides substantial grants to local governments and law enforcement agencies to combat street art (Moreau and Alderman 109). Their slogan, “Together, we keep America beautiful,” begs the question: which Americans are granted the privilege of creating “beautiful” things and at whose expense?

When marginalized individuals are systematically neglected and relegated in the art world, many turn their creative ventures inward, creating public works in and for their own communities. Amidst debates over the acceptability of certain forms of art, it’s crucial to remember that the act of creating art itself is not inherently illegal. If we consider all forms of artistic expression as sacred — as manifestations of human creativity — then street art, in particular, holds a special significance. It serves as a repository for the untold stories and silenced voices of marginalized communities throughout history.

A Case Study of Washington D.C.

Washington, D.C. is an ideal setting to explore this phenomenon. Its diverse neighborhoods and dynamic demographics create a captivating urban canvas. In his case study on anti-Trump graffiti in D.C., Jeffrey Ian Ross, a professor and research fellow at the University of Baltimore, takes note that despite experiencing graffiti and street art for decades, and being home to renowned artists like Cool “Disco” Dan, the city has never been recognized as a hub for this art form (Ross 128). This is in part to blame on the active involvement of Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), whose cleanup crews diligently patrol streets to promptly remove unauthorized markings, including litter, trash, and graffiti (Ross 130). It would be reasonable to assume that there are decades of graffiti and street art that have been all but lost to gray paint rollers and pressure washers. In a democratic society, governments are duty-bound to establish environments that mirror the concerns and preferences of their populace. Street art is one of the truest forms of concern or preference, created by citizens unsatisfied by their public spaces. As such, its erasure stands in direct opposition to democratic values.

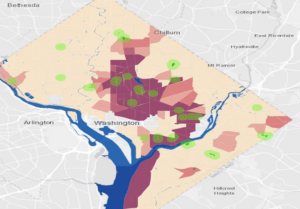

This erasure of identity has massive ramifications. The true history of Washington D.C. is all too often overlooked. Like many facets of Washington, there’s an undeniable undertone of racism in the assertion that the city lacks a significant history. As reported by Blair Ruble, distinguished fellow at the Woodrow Wilson center, in actuality, dismissing the District of Columbia as a vibrant community, home to tens of thousands of American citizens, was employed as a pretext to justify the suspension of local political autonomy, occurring in what was the first major American city with a majority African American population (Ruble 60). This fact could only be hidden through a methodical erasure of community history. According to her map showing D.C.’s gentrification, Sarah Bretschko, who holds a masters in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science, displays how some of the most intensely gentrified areas from 1990-2016 overlap with new green spaces.

Bretschko, Sarah, September 15, 2021, ArcGIS StoryMaps

This points to a direct conflict between the citizens and governmental views of public space. The government could have democratically worked with citizens to figure out how to create usable public spaces to benefit those who were already there, but instead, autocratically pushed black folks out of their communities and replaced socially constructed spaces with manufactured “natural” ones. This is one of the reasons D.C.’s modern neighborhoods are so segregated.

Cities are not homogeneous and this hold true for their street art. Ashley J. Holmes, Director of teaching effectiveness and professor of English at Georgia State University localizes the graffiti scene in her description of “local publics and counter publics.” These are spheres in which “issues, ideas, and identities circulate and resonate in localized ways” (Holmes 40). The street art in Ward 3, the wealthiest ward in D.C., will vary drastically from street art in the poorest ward, Ward 8. Though not far from one another, the street art in each location is distinct to its residents.

This effect is especially fascinating in segregated neighborhoods. With Howard University at its core, the U Street District emerged as a vital hub for African American economic, cultural, and spiritual life in a segregated D.C. during the Jim Crow era. Recognized colloquially as “Black Broadway,” this vibrant neighborhood once boasted over 200 black-owned establishments frequented almost exclusively by African American patrons (Hyra 5). Upon D.C.’s desegregation and the influx of black families into formerly restricted venues, U Street witnessed a dramatic decline in its economic vitality. Subsequently, white-owned businesses began to dominate the neighborhood, gradually erasing the vibrant legacy of “Black Broadway,” which now exists primarily in the narratives and recollections of its former inhabitants.

The true peril of the ongoing gentrification in the U Street area lies in the tendency to view the neighborhood and the city solely through the lens of urban theory. The term urban renewal inevitably weasels its way into every discussion involving displaced communities. According to Britannica, urban renewal refers to the process of revitalizing urban areas through various redevelopment initiatives. However, it often serves as a guise for gentrification, wherein affluent interests displace existing communities, typically low-income or minority populations, in pursuit of economic gain and urban beautification. Unfortunately, this narrative can be found in virtually every city in the United States. We are compelled to question whether the vibrant essence of U Street will be drained in the pursuit of so-called “improvement.” Should this occur, the U Street community risks forfeiting its most invaluable asset: its ability to cultivate beauty.

Photo by Nathan-Slarskey, 2024, U-Street

Imagery of Black icons and Black joy pervade the U-Street mural scene. In this image, we see vibrant depictions of some D.C. natives: Chuck Brown, one of the founders of D.C.’s Go-Go style music, Taraji P. Henson, an accomplished actress, Golden Globe and 4-time Emmy winner, and Howard graduate, and Wale, a Grammy nominated rapper known for blending hip-hop and go-go styles, among others.

Photo by Nathan-Slarskey, 2024, U-Street

A personal favorite, this mural depicts giants of music Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday, and Miles Davis. The image not only creatively expresses the genius and grandeur of these figures, but also exemplifies a key tenant of street art: its capacity to evolve. In the bottom left corner, another artist has left their tag. In doing so, the mural becomes familiarized. It now honors greats of musical art as well as the graffiti artists who paved the way for these muralists.

Street art has a remarkable ability to transform alien spaces into welcoming sanctuaries, infusing them with a sense of warmth and familiarity through evocative language and vibrant imagery. It fosters a sense of connection to the location, inspiring people to rediscover and cherish it. Amidst the alienation wrought by gentrification, reclaiming and revitalizing space for communal use becomes paramount.

Bridging Community and Classroom

It is important to consider why certain cities are known more for their history than others. Take, for example, the substantial corpus of work on Chicago, a city widely recognized for its rich history. Ruble claims that this wealth of knowledge emerged as a result of academic advisors at institutions like the University of Chicago, and later, other schools in the city and region, encouraging their students to venture into the streets and conduct research firsthand (Ruble 61). This strategy is excellent as it is applicable anywhere and involves students learning, directly, about the lesser-known communities within city in which they reside. Where better to look for insight into a community than street art?

Public art is crucial in furthering literacy education and intercultural communication. It serves as a catalyst for critical commentary, sparking meaningful dialogue within communities and facilitating the journey towards mutual understanding and respect amidst diverse perspectives. Holmes explains the necessity for widespread education on public art perfectly. “Preserving democracy and our roles as active, engaged citizens means paying attention to ‘how we educate our youth’ through the stories that are told in the non-commodified spheres of our public culture” (Holmes 38). This highlights the critical role of education in shaping the civic consciousness of future generations, emphasizing the need for curricula that prioritize diverse narratives and experiences found within the uncommercialized realms of public culture. To not look to street art and its creation for truthful insight into a community, constitutes a gross neglection of the trove of public writing put forth by its members. Additionally, this ignorance perpetuates the systematic disempowerment and erasure of heritage used to keep communities marginalized.

Education traditionalists may argue that we ought not to get rid of traditional subjects in favor of these more “progressive” areas of study. Anthony O’Hear, professor of Philosophy at The University of Buckingham, states that “An education which is not firmly based in traditional disciplines is easy game for any sort of political manipulation” (O’Hear 104). Additionally, he argues that you must have a secure basis within your own culture before judging others (O’Hear 103). This limited framework for understanding education is precisely the reason humanity is so divided. While traditional disciplines provide a solid foundation, an education solely rooted in them risks stifling critical thinking and creativity, leaving students ill-equipped to navigate a rapidly evolving world. By embracing diverse perspectives and interdisciplinary approaches, education can foster resilience against political manipulation while nurturing well-rounded individuals capable of adapting to complex challenges. Thus, students are rendered capable of shaping themselves into more active, participatory members of a democracy.

There are a number of ways one can teach others about a community, yet none come anywhere close to the level of a well implemented community-based learning course. Robert G. Bringle, Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Philanthropic Studies and Senior Scholar in the Center for Service and Learning at Indiana University and Julie A. Hatcher, Associate Professor of Philanthropic Studies and Executive Director of the Center for Service and Learning at Indiana University, explain the benefits of, and outline a plan for implementing a community-based course. They found that students enrolled in community-based learning courses exhibit more favorable course evaluations, develop positive attitudes and values towards community service, and achieve higher academic performance on mid-term and final examinations (Bringle and Hatcher 223). Moreover, additional studies corroborate the assertion that community-based learning yields beneficial effects on personal growth, attitudes, moral development, social skills, and cognitive outcomes (Bringle and Hatcher 223). For a course to be successful, they explain the need to, “Document the implementation of service learning (monitoring) and the outcomes of service learning (evaluation)” (Bringle and Hatcher 224). That being said, here is my proposal for a community-based learning course on Street Art:

Course Description: This community-based class seeks to harness the transformative power of street art to strengthen bonds, foster creativity, and revitalize public spaces within our community. Through hands-on workshops, collaborative projects, and engagement with local artists, participants will explore the rich history and cultural significance of street art while actively contributing to the beautification and cultural enrichment of our neighborhoods.

Learning Objectives:

- Explore the history and evolution of street art as a form of cultural expression.

- Understand the role of street art in community building, social activism, and urban revitalization.

- Develop practical skills in street art techniques such as stenciling, wheat-pasting, and mural painting.

- Engage with local artists and community leaders to identify opportunities for collaborative projects.

- Foster a sense of ownership and pride in public spaces through the creation of community-driven street art initiatives.

- Promote dialogue and understanding across diverse perspectives through the medium of art.

- Reflect on the ethical and legal considerations surrounding street art, including issues of vandalism and property rights.

Course Structure:

- Week 1: Introduction to Street Art: History, Origins, and Cultural Significance

- Week 2-3: Exploring Street Art Techniques: Stenciling, Wheat-pasting, and Mural Painting

- Week 4-5: Collaborative Projects: Engaging with Local Artists and Community Partners

- Week 6-7: Street Art and Community Identity: Reflecting Local Stories and Values

- Week 8-9: Public Space Activation: Transforming Neglected Spaces into Vibrant Art Installations

- Week 10-11: Dialogue and Reflection: Ethical Considerations and Community Impact

- Week 12: Culminating Exhibition: Showcasing Community Street Art Projects and Celebrating Achievements

For activities I referenced Artist and Art Educator Jennie Drummond’s article “3 Ways to Grow Community Connections Through Graffiti in the Art Room.”

This course aims to teach students to challenge restrictive societal norms and assumptions. Exploring urban environments through street art not only fosters the notion of cities as canvases for creative expression but also prompts reflection on the intricate dynamics surrounding freedom of artistic and cultural expression in public domains (Keys 99). On street art education Holmes states, “Students learn to maintain their critical and analytical eye in what are typically considered non-academic spaces” (Holmes 42). After taking this course, students will recognize the visual aspects of cultural heritage prevalent in reclaimed public spaces.

Conclusion

In a democracy, it is the responsibility of governments to ensure that public spaces align with the interests and needs of the people they serve. When citizens feel marginalized or excluded from these spaces, it is reasonable for them take it upon themselves to shape them into better reflections of their collective identity and values. In our contemporary landscape where marginalized perspectives are frequently stifled and communal areas are progressively commercialized, street art emerges as a potent vehicle of artistic defiance, revitalizing and democratizing public spaces. Incorporating street art into educational programs rooted in community engagement serves as a vital means of safeguarding cultural history and nurturing active civic participation. Furthermore, it plays a pivotal role in empowering marginalized groups to assert their unique narratives and identities amidst the challenges posed by gentrification and entrenched systemic disparities. My point here that street art should be taught, cherished, and thus more widely recognized should interest educators and researchers. Beyond this limited audience, however, my point should speak to anyone who cares about the larger issue of systemic inequality. Street art is the repository of the unheard. The first step in achieving an equitable society is to listen to those who have been sidelined. To stifle the voices of street artists, to suppress their creativity in the name of order or propriety, is to deny them their autonomy and rob society of the vibrant tapestry of ideas and perspectives that enriches the human experience. Street art is not merely an academic endeavor — it is a moral imperative, a testament to the diversity, resilience, and boundless creativity of the human spirit.

Works Cited

Data USA. “Archivists, Curators, & Museum Technicians.” Datausa.io, 2021, datausa.io/profile/soc/archivists-curators-museum technicians#:~:text=Race%20%26%20Ethnicity&text=85.4%25%20of%20Archivists%2C%20curators%2C.

Bretschko, Sarah. “Mapping Gentrification in Washington, DC.” ArcGIS StoryMaps, 26 Jan. 2022, storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/90e0c4403ee74ec8ad987851f00ca6aa.

Bringle, Robert G., and Julie A. Hatcher. “Implementing Service Learning in Higher Education.” The Journal of Higher Education, vol. 67, no. 2, Mar. 1996, p. 221, https://doi.org/10.2307/2943981.

Campos, Ricardo, et al. Political Graffiti in Critical Times : The Aesthetics of Street Politics. New York, Berghahn, 2021.

Drummond, Jennie. “3 Ways to Grow Community Connections through Graffiti in the Art Room.” The Art of Education University, 14 Mar. 2022, theartofeducation.edu/2022/03/mar-3-ways-to-grow-community-connections-through-graffiti-in-the-art-room/.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Urban Renewal.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 25 May 2017, www.britannica.com/topic/urban-renewal.

Hyra, Derek. “Selling a Black D.C. Neighborhood to White Millennials – next City.” Web.archive.org, 4 Apr. 2018, web.archive.org/web/20180404194231/nextcity.org/features/view/washington-dc-real-estate-branding-white-millennials. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Keys, Kathleen. “Contemporary Visual Culture Jamming: Redefining Collage as Collective, Communal, & Urban.” Art Education, vol. 61, no. 2, 2008, pp. 98–101, www.jstor.org/stable/27696284?seq=1. Accessed 29 Mar. 2024.

Moreau, Terri, and Derek H. Alderman. “Graffiti Hurts and the Eradication of Alternative Landscape Expression.” Geographical Review, vol. 101, no. 1, 2011, pp. 106–124, www.jstor.org/stable/41303610?seq=5. Accessed 2 Apr. 2024.

O’Hear, Anthony. “The Importance of Traditional Learning.” British Journal of Educational Studies, vol. 35, no. 2, 1987, pp. 102–114, www.jstor.org/stable/3121439, https://doi.org/10.2307/3121439. Accessed 8 Sept. 2021.

Ruble, Blair A. “Why Washington History Matters: Lessons from U Street.” Washington History, vol. 23, 2011, pp. 59–63, www.jstor.org/stable/41317469?searchText=U-Street&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3DU-Street%26so%3Drel&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Ab097c3dd95525157d0d54ae240f497a9&seq=2. Accessed 2 Apr. 2024.

Unwin, Tim. “A Waste of Space? Towards a Critique of the Social Production of Space…” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 25, no. 1, 2000, pp. 11–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/623315. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Wall, Kelly. “A Brief History of Graffiti – Kelly Wall.” TED-Ed, 8 Sept. 2016, ed.ted.com/lessons/a-brief-history-of-graffiti-kelly-wall.