The Unaliving of Online Political Discourse: TikTok’s Algospeak as a Euphemistic Marketing Tool Reinforcing the Fantasy of Participation

Isabel Taylor

Introduction

The new age of social media is characterized by algorithms, large numbers, and advertisements. Users log on to whichever-platform, along with billions across the globe, expecting to see content catered precisely to their taste. In between standard posts produced by fellow users, ads intrude, and on single-medium platforms like TikTok, these ads can be nearly indistinguishable from regular, unsponsored posts. This highly commercialized environment has led to the development of coded languages that allow for the navigation of algorithmic restrictions. TikTok’s political communities in particular have created algospeak, a linguistic variation of English doctored specifically to the preferences of TikTok’s automated moderation systems. This phenomenon, at first glance, appears to empower users by enabling them to continue discussions on controversial issues regardless of the platform’s suppression. However, viewed through Jodi Dean’s (2005) theory of communicative capitalism, algospeak becomes a part of a deeper paradox. Dean argues that online activism fosters a “fantasy of participation,” where interactions feel politically meaningful but serve simply as contributions to an ever-moving stream of content–benefitting only the platforms by increasing engagement rather than the political community by advancing authentic discourse. Algospeak, while intended to bypass restrictions, ends up reshaping discourse to suit the conventions of the platform, transforming complex conversations into consumable content that reinforces what is purely a fantasy of civic engagement.

Theoretical Foundations

Communicative Capitalism & TikTok

Jodi Dean’s (2005) observations of the relationship between online activism and the material response of governments have become foundational in the field of both political science and technology and one of the bases for which new social media is understood. I will be employing one of the proposed cogs of Dean’s (2005) broader mechanistic theory as the lens through which algospeak–when used in political content–is not functioning as a tool for linguistic communication, but rather as a tool for the marketing of a commodity.

It is not controversial to say that people are far more willing to share vulnerable aspects of themselves, contentious opinions, or their more impertinent observations online than they are face-to-face. While it can be argued that this trend is due to the physical distance between the sharer and the facial expressions, body language, and verbal reactions of their audience, Dean (2005) proposes that individuals are more willing to “[contribute] to the infostream” precisely because they believe there is a digital community out there in which their thoughts and ideas are received and reacted to. Dean (2005) terms this pattern the “fantasy of participation.” This illusion is particularly problematic in the realm of democratic politics, as a growing number of individuals feel civically fulfilled by “clicking a button, adding their name to a petition, or commenting on a blog” (Dean, 2005, p. 60) and therefore do not materially engage.

The fantasy of participation can be found in effect on the majority of internet spaces–think of Blackout Tuesday, in which Instagram users showed solidarity for the Black Lives Matter movement by posting a solid black square to their page, or the biting discourse that daily occurs in all subjects political on X (formerly Twitter), or the extensive conspiratorial theories characteristic of Reddit–engagement with politics can be found on virtually any platform. However, for the purposes of this essay, I will be focusing on TikTok. This choice is largely due to the platform’s stark rise in demand in the United States, as well as the popularity of the app to be used as a location for the dissemination of political news, information, and conversation.

The prevalence of this form of use is likely due to TikTok’s development as a hotspot for any form of advertising. Joshua Needleman (2024), a writer for Marketing Brew, reported that over the course of 2023, 30,000 companies invested a combined $3.8 billion into TikTok for the purpose of marketing their brands and products. This flood of ads–combined with the rise of influencers–has generated an intensely capitalistic culture. Users log into TikTok with almost the same attitude as a customer stepping into a shopping mall; they are expecting to see items worth purchasing, lifestyles worth replicating, meals worth cooking, and ultimately: civic practices worth mimicking. Pew Research Center reported that, as of 2024, one-in-three adults in the United States use TikTok. This statistic increases to six-in-ten for U.S adults under the age of 30 (Eddy, 2024). Moreover, four-in-ten young adults aged 18-29 report regularly getting some or all of their news from TikTok, a ratio that has doubled since 2020 (Leppert & Matsa, 2024). These statistics indicate that TikTok’s platform has become a cultural hub for young adults to build civic efficacy intrinsic to engaging in political socialization.

Algospeak

The term algospeak was coined by former Washington Post columnist Taylor Lorenz in her article “Internet ‘algospeak’ is changing our language in real-time, from ‘nip nops’ to ‘le dollar bean’.” She describes it as a system of “code words or turns of phrase” that TikTok users employ to avoid content moderation systems (Lorenz, 2022). For the purposes of this essay, I will be using Kendra Calhoun and Alexia Fawcett’s definition of linguistic self-censorship, which expands to include linguistic changes TikTok creators make to engage in mimetic language play (Calhoun & Fawcett, 2023). My inclusion of this definition is for the sake of my later discussion of how algospeak functions within the context of social marketing, as humor is often employed in advertising.

Algospeak is not unique as far as online linguistic developments. Leet (also known as 1337), for example, is a form of English developed on bulletin board systems, characterized by its substitution of letters with numbers or symbols (Stano, 2023). Leet first appeared in the 1980s (Stano, 2023) and has long since spread outside of its original platform. What differentiates algospeak is its use of emojis, metonymic substitutions, and homophones or homophonous stand-ins. Often, more than one of these linguistic tools will be at play within one term. For example, the corn emoji (🌽) is often used when a creator is referencing pornography. First created because of the rhyme, then further simplified to the emoticon. Another instance is “le dollar bean”, which began as the leet form of lesbian (le$bian), then further developed because of TikTok’s text-to-speak pronunciation (Stano, 2023).

The layering of linguistic devices that characterize algospeak makes it particularly context-dependent. While the majority of English-speaking internet users will be able to decipher the replacement of Es with 3s, Ls with 1s, or As with @s–not every user is guaranteed to translate “leg booty” to LGBTQ (Lanez, 2022). The intricacy of algospeak’s features makes it especially impactful when terms “breach containment”. In August of 2024, Seattle, Washington’s Museum of Pop Culture released their “27 Club” exhibit, which featured the following: “Kurt Cobain un-alived himself at 27, placing him in the company of other artists who passed at that same age under tragic circumstances” (Museum of Pop Culture, 2024). This excerpt (posted on an X account that has since been deactivated) coasted the internet wave of controversy as hundreds of thousands of critiques of the museum’s insensitivity rolled in (Goldberg, 2024). Additionally, discussion was sparked in the field of mental health, as many grew concerned that the proliferation of a euphemistic synonym for suicide represented a greater movement toward further stigmatization of mental health disorders (Goldberg, 2024).

This instance of algospeak reaching outside the bounds of TikTok–and therefore, reaching those who do not recognize or understand it–brought the ongoing discussion surrounding the dialect to the surface. Simona Stano (2023) and Heather Tillewein, Keely Mohon-Doyle, and Destiny Cox (2024) all argue that algospeak enables users to have conversations on loaded topics, such as sexual violence, mental health, and racial discrimination, while still permitting TikTok its legal obligation to censor potentially harmful content (Tillewein, Mohon-Doyle & Cox, 2024). Stano’s (2023) proposal is that algospeak–and other Internet language varieties–afford users an avenue of “linguistic empowerment”, which enables them to more effectively avoid the speech suppression that occurs with automated content moderation systems. On the other hand, Kat Rosenfield, a writer for Reason magazine, maintains that digital self-censorship sets a bad precedent for the future of free expression, particularly for content creators (Rosenfield, 2023).

Methodology

Disclaimers & Methods of Selection

I will be analyzing the marketing functions of three different pro-Palestinian TikToks related to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. The two nations have had hostile relations since the Arab-Israeli War and the proclamation of Israel as a nation in 1948. Recently, tensions rose to the center of media attention following the violent attack by the terrorist group Hamas on October 7th, 2023. For the sake of ideological balance, I had planned to analyze posts by both pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli creators. However, an overwhelming majority of TikToks posted on the issue are pro-Palestinian, with 6.3 million posts under #palestine as of November 11th, 2024–nearly double the amount posted under #israel, which is sitting at 3.5 million. While the hashtags alone do not reflect the sentiment of individual videos, there is a distinct bias that made searching for pro-Israeli content that possessed the features I was looking for incredibly difficult.

My qualifications for selection were as follows: over 500,000 views, over 100,000 likes, an open comments section, and containing at least two instances of algospeak. The reasoning behind the necessity of a high number of likes and views is due to the implications of marketing analysis. The nature of my argument is not only that algospeak is an advertising tool, but that it is an effective one. Blue Atlas, a business-to-business marketing company, defines marketing effectiveness as a measure of how “marketing actions positively influence the final business outcomes” (Measuring Marketing, 2023). Within the landscape of communicative capitalism, engagement is the capital, and is thus the final business outcome. Videos with low engagement run the risk of employing algospeak ineffectively.

The necessity of an open comments section is similar in reason. To meet the qualities of the widespread fantasy of participation that I am arguing for the existence and significance of, there must be an illusion of conversation. While engagement metrics (likes and views) are important in contributing to the perception of abundant support, they do not capture the “substance” of the audience’s response. There were many videos that were over the threshold I set for those metrics, but the creators or the platform’s moderation systems had closed comments. This is often done when a large proportion of the comments on a video violate TikTok’s community guidelines.

While there were many videos posted in favor of Israel that fit all three of my requirements for engagement metrics, difficulty arose in identifying videos that employed algospeak. This is likely due to the assumptions made by the majority of TikTok users that TikTok’s automated moderation systems disproportionately punish marginalized communities and the movements and ideologies related to them. Calhoun and Fawcett (2023) observed that this sentiment led to the prevalence of linguistic self-censorship in the first place, as marginalized creators–noticing that much of the content that reflected their experiences was taken down–began experimenting with ways to avoid it. The United States and Israel have been allies since the younger nation was proclaimed in 1948. This means that being in support of Israel lacks the context of expected suppression that being a part of a marginalized group does. Being pro-Palestinian, on the other hand, is weighed by the history of the 20-year War on Terror and the stark rise of islamophobia and discrimination against those of Arab descent that was concomitant. This, combined with the growing trend of antisemitism and pro-Palestinian sentiments being or being perceived as intertwined makes it so pro-Palestinian posts disproportionately employ algospeak as compared to pro-Israeli posts.

In a similar fashion to Tillewein, Mohon-Doyle, and Cox’s (2024) selection of posts in their critical discourse analysis of self-censorship in discussions of sexual assault, I identified the three cases featured in this essay through a series of hashtags. Searching by keywords is often unreliable due to the intervention of TikTok’s algorithm, which attempts to guess what the user is searching for rather than solely producing results that fit the search requirement. The three posts that I’ll be discussing in this essay were found through the following sequence of hashtags: #palestine, #propalestine, #freepalestine, #free🍉, and #🍉. The watermelon emoji itself is an example of algospeak, which I will discuss further in the analysis portion of this essay.

For a final clarification of the limitations and acknowledgement of potential biases of this analysis, TikTok is an intensely algorithm-dependent platform. No individual’s “For You” page (the main page on TikTok which features suggested videos) or search results will be the same as another’s. While I attempted to mitigate this by searching by hashtag and limiting my interaction with videos to viewing them, I have been using the platform since 2020, so years of the app’s interpretations of my preferences are still active. This is another reason I prioritized videos with high engagement and viewership, since they will reflect the preferences of a much larger population.

Further, I neither support nor denounce the beliefs reflected in the videos analyzed. My argument is not centered around any one issue, but rather, it is based on a generalization of all forms of political discussion on the platform. Additionally, none of the analysis or interpretation of these videos is intended to reflect on the creators themselves and this essay is not meant to criticize the creation of political content. For this reason, I do not include the usernames of the creators of these videos. The nature of politics in new social media is not the fault of any one group or individual; it is simply the result of the natural imbalances that occur between the time of new technology’s introduction and the implementation of regulation.

Aspects of Linguistics in Marketing

For the analyses of the selected posts, I will first define the connection between algospeak and euphemisms that occur in traditional English. For this purpose, I will be using Gerry Abbott’s (2010) understanding of euphemisms as secondary modes through which we mitigate, downplay, or distract from topics or terms that may violate the norms of social etiquette. The popularity of this particular device in advertising is no shock, as the marketer will aim to protect both their company’s repute and the “face” of their consumer (Crespo-Fernandez, 2022). Algospeak is often euphemistic in nature; it softens the blow of the conversation, packaging it for acceptance under the platform’s community guidelines. In this way, creators are protecting their repute in a similar way to businesses, with both a legal shield and a safeguard against terms deemed socially “problematic”. At the same time, they are ensuring the dignity of their viewers by maintaining the facade of a serious discussion.

To further the foundations of algospeak’s qualification to be analyzed as a part of “advertising discourse”, I will be using Elena A. Danalina, Ekaterina E. Kizyan, and Daria S. Maksimova’s (2019) three distinguishing features of said discourse: “it is guided by its own structure; it bears speech restrictions [and] it is determined by context” (p. 9). While algospeak is constantly adaptive in nature, it still has a structure that these adaptations occur within the bounds of; this being the replacement of certain terms with euphemistic or metonymic equivalents and the replacement of certain letters within “trigger words” with numbers or symbols. While the structure is internal, the “speech restrictions” are applied due to expectations of actions from the receiving end–TikTok’s moderation systems for legal restriction and reaction from the audience as social restriction. Lastly, the employment of algospeak is dependent on the context it is employed in. A creator using it effectively will not use algospeak casually; it is implemented in videos aimed to evoke a strong emotion, to call their viewers into action, or it is used in videos parodying the aforementioned types.

Additionally, Danalina, Kizyan, and Maksimova (2019) propose that advertising text is created using “media language”, with media language defined as a “complex means of expression” and “a set of material and intellectual values” (p. 11) hosted by the field of that market. In the case of algospeak as a whole, the complexity of expression is possessed by the nature of the language itself. For the three TikToks featured in this essay, the values will generally align with the political left-leaning audience that the three creators are appealing to. However, I will address the different particularities of these audiences on a case-by-case basis.

For each of the three videos, I will be identifying their exhibition of the following: contextual and intertextual congruency, circulation, and clarity. These terms come from Danalina, Kizyan, and Maksimova’s (2019) assertions of what an advertising text must display. Contextual congruence refers to the correspondence of the ad’s text with the context it is placed in, while intertextual congruence refers to the correspondence of the ad within the context of all previous exchanges (Danalina, Kizyan & Maksimova, 2019); in this case, other TikToks either on the same topic or from the same creator. Circulation in this context (not to be confused with Jodi Dean’s (2005) circulation of content) refers to the “[reproduction] through replication” (p. 12). In this analysis, circulation will be used to track the repetition of certain terms or styles within the text of the posts. Clarity will refer to the general ability of the audience to interpret the aims of the creator and the ease with which they are swayed.

Cases & Discussion

All data was recorded on November 11th, 2024 at approximately 12 p.m. In-video text, captions, and hashtags are recorded with the same grammatical conditions as they appeared within the posts.

Video 1

| Engagement Statistics | In-video Text | Caption | Hashtags |

| 127.1k likes

11.9k comments 886.2k views 15.6k saves 11k shares |

“ASMR for 🍉100% of the earnings of this video will go to a family in need in Gaza. I chose a specific family to help as their story resonated with me.

Interacting with these 3 buttons makes sure the revenue of this video goes 📈📈📈 I know a lot of my viewers want to donate but can’t afford it at the moment ♥️ so this is an easy way to donate: watching this video for one minute The family I chose was hiding in Rafah and are now on the run. They have 2 boys named Yousef and Yazan. The youngest is 3 years old. It’s almost over I promise ♥️🍉♥️🍉 If you want to donate $ directly to the family I chose, feel free to go straight to their GoFund me on the link on my bio” |

“I will share a screenshot of the proceeds in the next few weeks 🍉” | #asmr #passthehat #operationolivebranch #asmrfor🍉 #🍉 #🍉🍉🍉#🍉🍉🍉🍉 #freepalestine #asmrfyp #asmrvideo #asmrtiktoks #asmrsounds #asmrfood #asmreating #asmrmukbang #asmrpersonalattention #asmrforsleep |

Analysis:

Video 1 was posted by a creator who does not typically post political content. Her page is doctored to create an automated sensory meridian response (ASMR). ASMR videos generally feature an array of quiet, colloquially deemed “satisfying” sounds, which range from the tapping of two objects together, crunching, chewing, and whispering. This genre of video became popular due to the calming effect many listeners report it causing. The nature of this account provides some background for the correspondence between the text–primarily the hashtags–and the context of the video. The last nine hashtags on this creator’s video are generic ASMR-related tags that can likely be found on the majority of the videos posted to this account. Tags like #asmrtiktoks, #asmrsounds, and #asmrpersonalattention are all searches that users seeking out ASMR would click on–not users who are looking to engage politically.

These hashtags, though they are at the end, are the clearest indicator that this creator is trying to maintain distance from the negativity that connotes politics. As a larger platform, she generates a portion of her income from TikTok, and while she may want to offer aid to the cause, she likely does not want to risk deterring too many of her followers from her account. She writes out only two clear political movements in the hashtags: #freepalestine and #operationolivebranch (a grassroots movement that focuses on fundraising for individual families affected in Gaza). In all other text featured in this video, Palestine is referred to with “🍉.” The watermelon has become a symbol of the Palestinian movement, dating back to the 1980s when the Israeli military shut down an art gallery for its use of the Palestinian flag’s colors. Watermelon, one of the many items depicted in the exhibit, began to appear in protests as a sign of resistance (Furman, 2024). This symbol transferred to TikTok, as pro-Palestinian communities expected similar suppression by TikTok’s automated moderation systems.

However, from observation, there is little evidence that the platform’s system targets videos with Palestine or Palestinian in the hashtags, caption, or in-video text. The emoji’s use is largely due to the intertextual conversation between the creators and videos centered around the Palestinian cause. The watermelon has become a symbol of solidarity in the fight against silence–even if that silence is not being inflicted by the platform itself, creators are demonstrating their alliance with those who do face real-world oppression.

It is also conveniently marketable. Video 1 features the creator in red-pinkish lighting playing with a foam watermelon in order to produce ASMR. She acknowledges that this video’s purpose is to generate money for the cause; however, she also dilutes this air of commercialization by referring to the like, comment, and share buttons simply as “these three buttons.” This is another demonstration of this video’s message within the context of all previous messages this creator’s audience has received. TikTok content creators and YouTube influencers frequently request their viewers to “like, comment, and share” or “like, comment, and subscribe” in order to increase the likelihood of their video being generated by the two platforms’ respective algorithms. The identification of these “buttons” has become associated with commercialist creators who lack subtlety when it comes to the fact that their content is created explicitly for money. To maintain the image of depoliticized morality, this creator is doing what she can to avoid any association with the aforementioned genre of content. This is seen again when she refers to the increased revenue of the video as “📈📈📈.”

This repetition of charitable intentions and solidarity–particularly, in absence of acknowledgement of the cause for the necessity of said charity and solidarity–works well for this creator’s repute as an account. Additionally, she repeatedly reaffirms the role her viewers play in helping this family. This is seen in the previously mentioned “[interact] with these three buttons,” as well as “watch this video for one minute” and “I know a lot of my viewers want to donate.” The dynamic this creator instigates and maintains with these phrases is one of the clearest articulations of the fantasy of participation. While her and her viewers’ efforts to help this family are incredibly valuable and should in no way be diminished, this is the most literal demonstration of thousands of people fulfilling their moral and political duty by pressing a button. And it is emphasized further by the comments themselves:

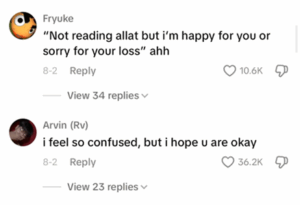

These are the first six comments that appear with the initial opening of the comments section. Notice: they are not a conversation. They are, essentially, playing an identical role as a like or share–an expression of support with minimal thought put towards engagement. This is not an entirely negative dynamic on a micro-level; further surface level interaction will allow this video to increase its engagement and raise more money for the family in need. However, as I will demonstrate in the analyses of videos 2 and 3, this is not an isolated incident. Political conversation and movement on TikTok is vacant of the depth and personal risk that has characterized successful political movements in the past.

Video 2

There was no caption written for this video.

| Engagement Statistics | In-video Text | Hashtags |

| 248.2k likes

5,497 comments 930.4k views 23.8k saves 7,189 shares |

“if when I say I am pro-Palestinian liberation you hear that I am pro t3rr0rism

“you have so deeply internalized the structure of ⚪ supremacy to the point that you have dehumanized Arab people because if I say Palestinian liberation and you hear t3rr0rism that means that you find the sheer existence of a group of people An innocent group of people t3rr0rizing and i know you are capable of separating a group of people from the government because I see you do it all the time ⚪ supremacy thrives off of verbal dehumanization of people And that’s why you wanna call me a t3rr0rist for supporting Palestinian liberation that is why you are equating Palestinian liberation with te3rr0rism and it is also why you will see the news calling black men thugs and Mexican men criminals and white men “lone wolves” now I grew up in a post 9/11 America with the last name Hosein This is not new to me but the fact that 20 some odd years later you are falling for the same propaganda the same rhetoric that has put not only this country but so many other countries into absolute ruin is reflective of the fact you want to believe that you are more human than other people” |

#freepalestine #ceasefirenow |

Analysis:

Unlike Video 1, Video 2 was posted by a creator who regularly posts political content. Her followers and those who regularly watch her videos expect significantly more engagement from her with political events, hence why she only tagged her post with two tags: #ceasefirenow and #freepalestine. These tags are some of the most popular of the movement and, unlike the first creator’s tags, will not be searched for by users who do not want to interact directly with the issue. In this video, the creator is accusing the opposition to the pro-Palestinian movement directly (see: use of “you”). However, both the creator and the viewers are aware that this video will not reach the audience that it seems to be addressing, which I will demonstrate later.

First, this creator applies algospeak for two different terms repeatedly throughout the video (which is approximately 1.44 minutes long). These terms are “t3rr0rism” or “t3rr0rist” and “⚪ supremacy.” She is applying both the letter-to-number substitution inherited from Leet and the modern algospeak substitution of metonymic emojis (in this case: a white circle for the “white” description of race). Note, she writes out “Palestinian” with no algospeech alteration a total of four times in the in-video text and once in the hashtags and her video has remained up, reinforcing the use of “🍉” online as a cultural signifier rather than a necessity. Her use of “t3rr0rism” is slightly more complex, for though she feels the need to censor it in text, she says it out loud and clearly every time it appears in the video. In TikTok’s “Transparency Center” page, they clarify that their automated moderation technologies go through a “variety of signals across content, including keywords, images, titles, descriptions and audio” (TikTok, 2024). Meaning that if “terrorism” was enough of a flag for the moderation system to strike it down regardless of the content of the video, the post would have been taken down due to her repeated, clear articulation of the term.

In combination with the use of the watermelon emoji, Video 2 demonstrates an additional layer of context to algospeak’s use: it is not, or it is no longer, necessary for communication about these subjects. Rather than the “linguistic guerilla warfare” Simona Stano (2023) proposed, algospeech has largely become a signifier of alliance with the left-leaning community on TikTok. To summarize, it has become symbolic. This is not a communicative tool used for the practical function of reaching out to the audience, it is a tool targeted at the audience’s associations with the other videos they have seen with that tool employed. In Danalina, Kizyan, and Maksimova’s (2019) words, it is a tool meant to emphasize the intertextual congruence of the present video with the past.

From a quick scroll through this creator’s account, she was highly active in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which provides context for her general focus on race throughout this video. Additionally, the BLM activist community on TikTok is one of the communities that popularized algospeak in the first place–partly due to the widespread use of ⚪ or “yt” instead of White when discussing the effects of systemic racism in the United States.

This creator’s videos also maintain the same righteous, often accusatory tone, so her typical audience is seeking out an affirmation of their anger and frustration at the systems they criticize. Her audience is not made up of those with differing opinions looking to learn, or even those with similar opinions looking to improve. Both the creator and her followers are likely aware of this on some level, since the majority of regular TikTok users have an idea of how the app’s algorithm functions. That is to say, people understand that, for the most part, they will not see what they do not want to see. From the anger that this creator inputs into her words, it is safe to assume that she understands that the statements she’s making would not be received well by the ideological opposition. Essentially, this is a performance of righteousness meant to reaffirm the position her audience already has–it is not educational, or even a space for learning. This is verified again by the comments.

The majority of the comments left on this video are simply users agreeing with what the creator has said. There is no conversation, critique, or reflection occurring. Occasionally, there would be a comment empathizing with the creator’s frustration directly, sharing similar exasperation in their own experiences in attempting to educate friends or family members. However, within the twenty-five top comments I read through, not one revealed the user identifying themselves as the “you” the creator is addressing.

While there is value in a strong bond with those you are organizing or in agreement with, this does not reflect a constructive conversation between opposing sides–or even a hostile debate. This video, which appears to be a letter directly to individuals of a particular viewpoint, was never meant to reach them. From the beginning, there was no intention for or want of critical response.

Video 3

| Engagement Statistics | In-video Text | Caption | Hashtags |

| 853.2k likes

3,234 comments 9m views 31.1k saves 6,630 shares |

“how many aura points did the older man helping me put on my graduation gown and when he saw my k3ffiyeh so i told him i was 🍉 & he turned around to show me his blazer had a solidarity pin” | “i think about him everyday bro it meant the worlddd” | #watermelon #graduation #csm #fyp #foryoupage |

Analysis:

Video 3 is very different from the previous videos in that it has a significantly broader audience. The creator of this video is not trying to speak to ASMR-listeners or pro-Palestinians, she is sharing an emotional story with anyone who comes across the post. The only restriction she places on her audience are found within these two aspects: the style of the in-video text and caption and #graduation.

Within the text she displays on the video itself, she refers to “aura points” and does not employ capitalization or punctuation. “Aura” is a recent trend in online humor popular with young adults and is used, comedically, as a measure of someone’s composure. Someone with low aura is implied to be awkward or ill-received, someone with high aura is implied to be impressive or respectable. Absence of capitalization is a texting standard common among teens and young adults. The #graduation would suggest this video to users who are graduating or near graduation at the time that this video was posted–since she does not specify the level of education, this narrows the range to approximately 17-25. Together, these traits imply that the creator is reaching out to others her age. Additionally, in the caption, she writes out “worlddd,” repeating the letter ‘d’ for emphasis of the significance of this experience.

However, other than the restrictions to a younger audience that I have described, this creator avoids narrowing the reception of her video any further. In her hashtags she includes #watermelon and #fyp. Unlike #🍉, #watermelon is largely made up of videos about the fruit in a literal sense. This is not a hashtag that would purposefully attract those looking for pro-Palestinian content. The other tag: #fyp, is commonly used by larger content creators in an effort to get their video placed on as many For You pages as they can. It is an intentional presentation of this video to anyone who may come across it. This widening of her viewer base led to the incidental revelation of the “bubble” that many ideologically-based online communities have found themselves in.

In absence of the restrictions placed by the creators of Video 1 and Video 2, this post found itself in an entirely different strain of the algorithm. It is reaching users who have not engaged, and do not intend to engage, with political content. Throughout the comments are those expressing confusion about the meaning of the watermelon and solidarity pin, whether this girl’s story is positive or negative, and so on. Most interestingly was the widespread confusion over the “k3ffiyeh.” This comment, and others similar in nature, clarifies that algospeak when it is adopting characteristics of Leet is interpretable by those unfamiliar with the context of the specific video. However, algospeak when it is contextual or metonymic in nature, is not easily understood by “outsiders,” even if they are on the same platform.

Conclusion

Before I further articulate the implications of the observations articulated in this essay, I must emphasize the limitations within it. Both the nature of TikTok’s algorithm and the nature of algospeak make it difficult to efficiently locate relevant posts. A more well-rounded study would feature the collection of a greater number of videos over a longer period of time in order to produce observations of greater accuracy. Additionally, these videos would be found from a greater variety of algorithmically generated preferences, rather than from a single individual. It would also be beneficial to institute an observational study of different ideological communities, not just the left-leaning community that I have discussed in this essay.

However, regardless of the limitations of this particular study, understanding the domino effect of commercialization on political discourse is imperative for activists, political scientists, and apoliticists alike. Discussion is the foundation for change–it is the stage at which a goal is identified, priorities are ranked, and compromises are reached. With social media as ingrained into our daily lives as it is, there is a great risk of further polarization of ideals in the United States–and for an ever-widening gap between the public and the government. These gaps must be addressed in order to avoid a stagnation of progress and the diminishing of the people’s democratic voice.

References

Abbott G. (2010). Dying and killing: Euphemisms in current English. English Today. 26(4), 51-52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078410000349

Calhoun, K. & Fawcett, A. (2023). “They edited out her nip nops”: Linguistic innovation as textual censorship avoidance on TikTok. Language@Internet, 21, 1-30. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/li/index

Crespo-Fernandez, E. (2022). Euphemism in laxative TV commercials: At the crossroads between politeness and persuasion. De Gruyter Mouton, 18(1), 11-35. https://doi.org/10.1515/pr-2018-0047

Danilina, E. A., Kizyan, E. E., & Maksimova, D. S. (2019). Euphemisms in advertising discourse: Putting on a positive face and maintaining speech etiquette. Training, Language and Culture, 3(1), 8-22. https://doi.org/10.29366/2019tlc.3.1.1

Dean, J. (2005). Communicative capitalism: Circulation and the foreclosure of politics. Cultural Politics, 1(1), 51-74. https://doi.org/10.2752/174321905778054845

“Demographic profiles and party identification of regular social media news consumers in the U.S. (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, X (Twitter), Reddit).” Pew Research Center, 5 Sep. 2024. https://bitly.cx/19wMT

Eddy, K. (2024, April 3). Six facts about Americans on TikTok. Pew Research Center. bit.ly/4hAiYt0

Goldberg, A. (2024). “A museum said Kurt Cobain ‘unalived himself.’ It sparked an important discourse about suidice.” USA Today, 14 Aug. 2024, https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/health-wellness/2024/08/14/kurt-cobain-unalive-suicide-language/74787682007/

Lanez, T. (2022). “Internet ‘algospeak’ is changing our language in realtime, from ‘nip nops’ to ‘le dollar bean’.” The Washington Post, 8 Apr. 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/04/08/algospeak-tiktok-le-dollar-bean/

Leppert, R. & Matsa, K. E. (2024, August 17). More Americans – especially young adults – are regularly getting news on TikTok. Pew Research Center. https://bit.ly/3Aydmio

“Measuring marketing effectiveness: A guide for business leaders.” Blue Atlas. 31 Mar. 2023. https://bit.ly/48Qv2CH

Museum of Pop Culture. (2024). The 27 Club. Seattle, WA.

Needleman, J. (2024, March 5). Brands spent nearly $4 billion on TikTok ads in 2023: report. Marketing Brew. https://bit.ly/3Z2FeEC

Rosenfield, K. (2023). “Stop spazzing out about ‘spaz’.” Reasons, January 2023, https://reason.com/2022/12/27/stop-spazzing-out-about-spaz/

Stano, S. (2023). Linguistic guerrilla warfare 2.0: On the ‘forms’ of online resistance. Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio. https://doi.org/10.4396/2022SFL13

TikTok. (n.d). Our approach to content moderation. TikTok Transparency Center. Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.tiktok.com/transparency/en/content-moderation

Tillewein, H., Mohon-Doyle, K., & Cox, D. (2024). A critical discourse analysis of sexual violence survivors and censorship on the social media platform TikTok. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-024-02987-2

Wijaya, P. E, Fisher, J., & Kirkman, M. (2024). Female genital cosmetic surgery in Indonesia: A qualitative analysis of medical advertising on Instagram. Culture, Health, & Sexuality, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2024.2341843

Yong, S. C. S. C., Gao, X., & Poh, W. S. (2024). The effect of influencer marketing on consumer engagement and brand loyalty. International Journal of Multidisciplinary: Applied Business and Education Research, 5(7), 2357-2364. https://doi.org/10.11594/ijmaber.05.07.02