Ornament

“You will not wear garments made of two colors.”

Leviticus 19:19

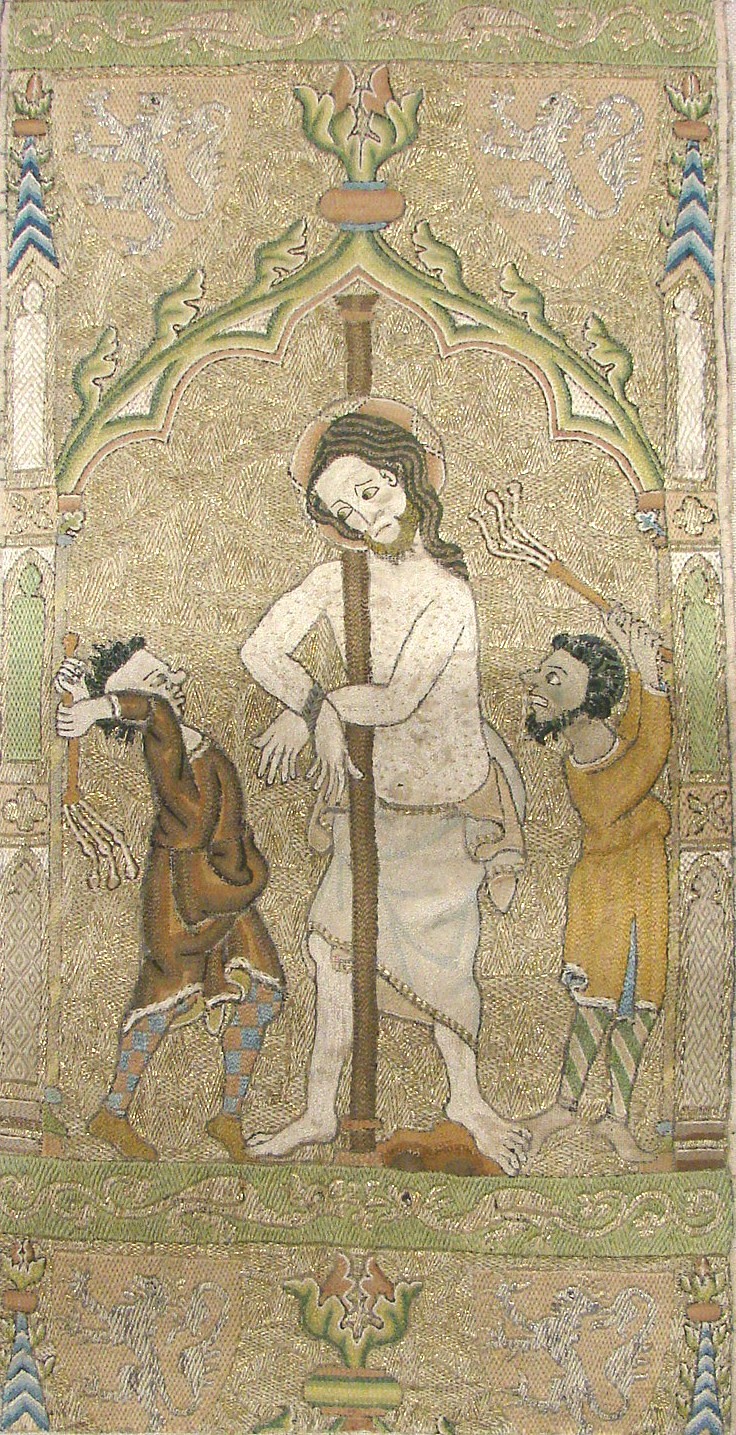

(Fig. 13) Unknown, Marnhull Orphrey (detail), 1310-1325. Embroidered with silver-gilt and silver thread. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Bodily adornments were deeply meaningful in the art of the Renaissance, an era in which clothing and accessories revealed (and sometimes concealed) sex, age, rank, wealth, occupation, and moral character.[49] Ruth Mellinkoff’s extensive research revealed how medieval and Renaissance artists, particularly in Germany and the Netherlands in the fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries, used pictorial attributes and other artistic devices to identify and denigrate figures deemed outcasts, including Jews, persons of African descent, and prostitutes. Among the visual evidence that she mined for her investigation are the patterns and colors of costumes, bodily ornaments such as jewelry, and physical attributes such as skin and hair color, blemishes, and gestures. According to Mellinkoff, clothing patterned with stripes and particolor, a pattern consisting of part solid color and part design, and that marked figures as “Others,” began to appear in art of the fourteenth century and continued on into later periods. In this section, I build from Mellinkoff’s work to demonstrate ways in which artists marginalized black Africans in images made for white patrons and audiences and came to be understood as conventions that “othered” their subjects.

In images of the late Middle Ages, each sartorial choice made by an artist held meaning: fabrics, colors, designs, and accessories were among the means by which social status was conveyed and upheld.[50] By 1500, striped fabric, pearls, and golden earrings had become key visual signifiers of Otherness, particularly in terms of race and sexual promiscuity, and these features had become conventions for representing marginalized groups and individuals.[51] The Old Testament book of Leviticus provided a foundation for correlating stripes with evil, for it strictly forbade them as a sartorial choice: “you will not wear garments made of two colors” (Leviticus 19:19). Choosing them for a garment was thus an affront to God and a risk to the soul.[52] Such pictorial marginalization effectively perpetuated the biases in which they were grounded.

An early example of a black African shown wearing a garment marked by stripes for the purpose of denigration is found in the Marnhull Orphrey (1310-1325) (Fig. 13), an embroidery that was sewn on the back of a chasuble worn by a priest in the Mass. Here, a figure in stripes appears in the scenes of Christ’s Passion, in particular in the Crucifixion. There is no basis in the Gospels for representing Christ’s tormentors as African, yet in the Marnhull Orphrey the figure on the right is shown with dark skin and wool-like, tightly coiled hair that identified a figure as black in art of this period. The figure on the left is paler in contrast to a tormentor depicted opposite; the former presents the dark loose hair and long nose stereotypical of representations of Jews. The black figure is drawn into proximity to the Jew, suggesting equal partnership in the murder of Christ, and the skin tone and exaggerated facial features are made more prominent by their stark contrast to the figure of Christ.[53] Stripes and particolor appear in stockings, tunics, hoods, and hose worn by Christ’s enemies, arresters, mockers, and flagellators.[54] Furthermore, the figures in the Marnhull Orphrey are shown with exaggerated facial features that define them as physically and spiritually ugly, characteristics that speak to visual denigration. Indeed, the artists who portrayed lesions, hunchbacks, bulging eyes, and crooked teeth were not simply expressing their interest in naturalism; rather, they were defining and marginalizing these figures.

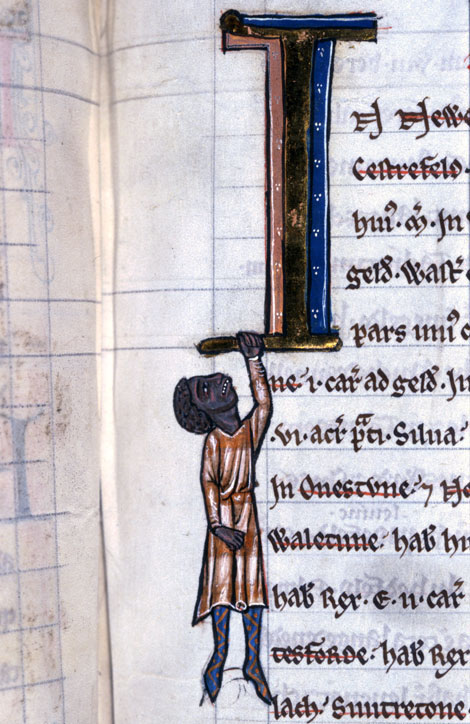

A black figure in the Domesday Abbreviato (c.1241) (Fig. 14) is dressed very similarly to the marginalized figures in the Marnhull Orphrey, illustrating the motives behind artists depicting the figure as the “Other.” This figure is shown dangling from the letter ‘I’ on a folio of the illuminated manuscript. It is marked by exaggerated facial features, wool-like hair, and dark skin. His short, striped tunic and patterned hosiery is a striking contrast to the black figures clothing seen in the Marnhull Orphrey illustrated above. These figures wear short tunics, in contrast to the long robes of certain figures there: The Virgin’s long gown and those of St John to the left of Christ, and Sts Peter and Paul on the left and right panels signal their comparatively higher status. The depiction of the lower-ranking individuals is equally suggestive on a comparative basis: the two men flaying Christ wear short tunics and variegated hose, indicating the standard low laborer status of all three othered figures in the two works.

Titian’s Diana and Actaeon of 1556-59 (Fig. 15) relies on sartorial conventions to comment on race through a mythological subject. Actaeon bursts onto the scene, causing alarm among Diana’s virgin nymphs, several of whom seek hastily to cover their nude bodies. Diana is seen to the right side of the painting wearing a crown with a crescent moon and is quickly covered by the dark-skinned woman who is known as her Ethiopian handmaiden. The black woman in the painting is seen wearing a large, red earring, blue ribbons throughout her hair, and a vibrant orange and white striped dress that hangs off of her shoulder to the left side. She is the only woman in the painting that is fully clothed, but none of the other women in the painting wear a distinctive pattern or color on their clothing as the black woman does (Fig. 15). The painting was commissioned for King Philip II of Spain, who allowed Titian exceptional freedom in choosing the subjects. The artist’s use of colorful stripes and an earring reveal his understanding of the established conventions for visually communicating European social hierarchies of race. Titian also incorporated the use of the earring on a servant in his painting, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (c.1570) (Fig. 16) and the use of stripes in the painting, Penitent Mary Magdalene (c. 1555-65) (Fig. 17) where multi-colored stripes and earrings help to define the Magdalene as a prostitute. Although the Magdalene chose to repent and follow Christ, artists such as Titian recalled her earlier sinful profession by casting her in rich costumes in her depictions or doubling her as the disreputable whore and as the sincere penitent.[55] It is through the works of Titian where we can see not only artistic expression but how artists used societal norms to depict the “other”.

(Fig. 16) Titian, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (detail), c.1570. Oil on canvas. Detroit Institute of the Arts, Michigan.

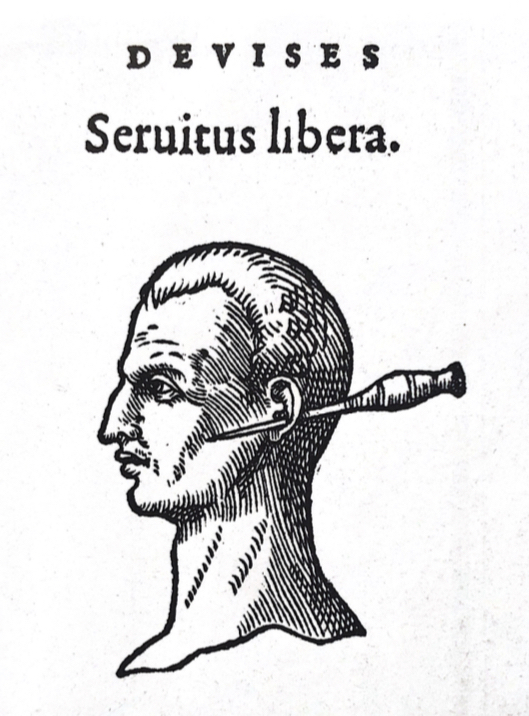

The earring seen on black Africans in Renaissance works could explain and possibly reveal whether or not the black African depicted was enslaved or an attribute of servitude. According to Elizabeth McGrath and Jean Michel Massing, Old Testament slaves who had been freed but still wished to stay with their masters, perhaps to remain in the care of the wealthy family, had their ears pierced with an awl, a small pointed tool used for piercing holes, often in leather.[56] Claude Paradin’s book, Devises heroïques, book of devices used the motif of ear piercing to illustrate the notion of voluntary slavery.[57] Paradin’s image of ‘Servitus libera’ with the head of a man enduring the procedure as seen in (Fig. 18). The Devises remained popular at least into the seventeenth century and in an observation of pictorial signs, a pattern of depictions of black Africans wearing earrings are seen in more northern works or art from England, Dutch, and Flemish artists.