Burning Desire

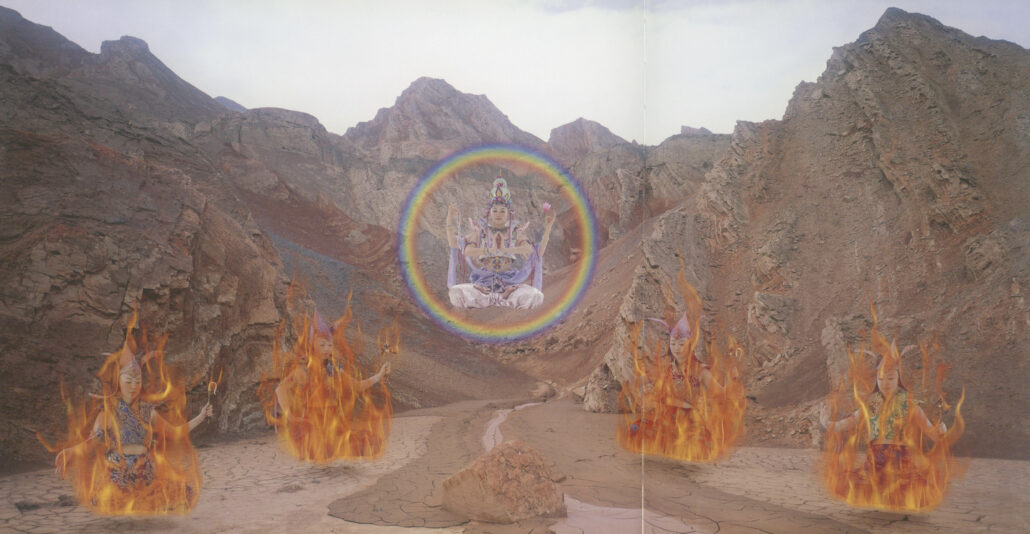

The second image in the series, “Burning Desire,” was created between 1996 and 1998 (Fig 11.) The background was photographed in Mongolia’s Flaming Cliffs in the southern Gobi Desert.[57] The site of the Flaming Cliffs is linked to Buddhism nominally and metaphorically. This site and Mori’s choosing it may allude to an episode from the Chinese novel Journey to the West, written in the 16th century by Wu Cheng-en during the Ming Dynasty.[58] The story surrounds the seventh-century Chinese Buddhist monk Xuánzàng’s travel to India in search of sacred texts. Consisting of 100 chapters, Journey to the West, or “Monkey King,” as it is often known, takes place in the wilderness for the bulk of the journey with Xuánzàng and his disciples on 81 adventures.[59] Within these chapters, there are flaming mountains, magical monsters, and even a kingdom ruled by women. Throughout the journey, the four disciples must bravely fend off attacks on their teacher Xuánzàng, from various monsters and situations. Either engineered by fate or the Buddha, no harm comes to the disciples. In the end, Xuánzàng must face one last disaster to attain Buddhahood.[60] “Burning Desire” may allude to the episode in which the disciples must endure and overcome a burning fire test, crossing through the fiery mountains that stretch 250 miles of flame to get to the West.[61] The story and the hot, dry desert itself are both testaments to perseverance and hardship one must endure on the path toward enlightenment.

Mori imposes herself on the floating deity, and the four figures are engulfed in flame. The four-armed bodhisattva hovers in a rainbow nimbus with her back two hands in the air, the right holding a rose, and the left holding a Buddhist rosary (Fig. 12). A bodhisattva is an important Buddhist deity that Mori frequently appropriates.[62] This figure is most likely a representation of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Infinite Compassion, as seen in a metal sculpture of Avalokiteshvara from 18th-century China (Fig. 13). In this sculpture, the figure holds the same objects as Mori, seated cross-legged with their front two hands in a similar mudra. In “Burning Desire,” Mori holds the same objects, and her thumb and pointer finger on each hand come together to mimic the vitarka mudra, a hand symbol in Buddhism that is used to signify discussion, teaching, and intellectual argument. The circle that is created by the joining of the fingers represents the wheel of law or dharma.[63] Her front two arms come together to create what looks like the Namaskara or Anjali mudra. This mudra is the gesture of greeting, prayer, and adoration rarely seen in images of enlightened Buddhas but more common in Bodhisattvas who are preparing to attain enlightenment.[64] This is an important factor in judging whether Mori’s creations allude to real Buddhist tradition because as a stage in her Esoteric Cosmos with “Pure Land” representing Nirvana, this placement is right where it should be on Mori’s journey to enlightenment. Mori is dressed in a traditional Indian costume, according to scholar Jungwhe Moon. However, once we zoom into the details of this image, we can see that the artist embellished this costume and character.[65] For example, Mori’s green hairdo is tied up into a tight bun with tresses of pink ribbon that fall on both sides of her face, almost as an extension of her hair. However, Avalokiteshvara commonly had dark blue hair tied in this exact way, as seen in an image of a bronze sculpture from 20th-century Bhutan (Fig. 14).[66] Tara is a female deity of Compassion and the female counterpart of the bodhisattva, whose Avalokiteshvara, who’s whole body is generally green in many representations. Tara is the protectress of navigation and earthly travel, as well as spiritual travel to enlightenment, making her an obvious choice by Mori, who’s creating a series on the journey to enlightenment.[67] Bodhisattvas have a physical form of a female among its many forms, Tara being one of them. The gender of bodhisattvas are often hard to distinguish, but Mori is clearly playing the role of a female deity.[68] There are countless details throughout Mori’s Esoteric Cosmos that do share similarities with esoteric Buddhist visual culture, but Mori continues to blend authentic religious tradition with her own creative touch to make it seem not completely unapproachable. You can find something familiar in her recreations of ancient religious tradition, for example, in the recognizable desert setting of “Burning Desire” or “Entropy of Love,” or in Mori’s soft features that the viewer can connect with. This familiarity creates a shared experience between the viewer and the artist.

Beneath and behind the figure of Mori as a bodhisattva are the rocky landscape of the desert. On either side of her appear four figures engulfed in flames, practitioners that follow the Buddha’s teaching. The flames, or the “fire of sensory-based desire,” surrounding the practitioners should extinguish once the state of nirvana is achieved.[69] They each hold a different object and make a different hand gesture but wear the same hat and different variations of the same outfit. The object in the hand of the disciple on the far left appears to be a whisk, a symbol that implies the overcoming of obstacles. The third disciple overholds a very similar object. The other two objects, in the hands of the second and fourth disciples, appear to be axed, which ward off calamity and help achieve calamity.[70] Although, it is clear that Mori did not intend for them to be exact replicas of the traditional objects. All of them make different mudras, the Gyan mudra on the left and the Prithvi mudra on the right two figures. Both mudras represent a seal, promoting healing and spiritual balance. Interestingly, Prithvi is also known as the “Earth Mudra,” as it can balance the earth element.[71] Although these details are not exact and are paired with completely made-up costumes that look almost extraterrestrial, Mori still finds a way to appropriate the traditions of Buddhism to produce her own meaning and creativity by using a mudra that represents earth for her series that encapsulates the elements of nature and spirit. She uses the iconography of esoteric Buddhism and her own creativity to piece together Burning Desire and provide another stage of the “Esoteric Cosmos.” The image is certainly more spiritual than feminist; however, using the story of the Monkey King, a journey about hardship and perseverance, with the inclusion of a female deity at the center of her story is a clear indication of equalist thinking.