Conclusion: Feminist Art in the Past and Future Tenses

The biography of each artist and the visual, feminist, and spiritual analyses of both the Needle Woman and the “Esoteric Cosmos” set the scene for a natural comparison in which we see how each artist views the world. In addition to feminism, Confucianism and Buddhism are also paramount to the understanding of the two women’s art. Mori and Kimsooja both address the subjects of feminism and spirituality, but in different dimensions and expressions, due to their backgrounds, ages, and country of origin. These attributions also create parallels between their art. Both artists and their works build on religion’s uniquely empowering quality for women and explore the questions about spirituality and gender in contemporary global art that I asked in the Introduction to this thesis.

Born ten years apart, the age gap between Kimsooja, 64, and Mariko Mori, 55, is an interesting component of my research. As I mapped out in the previous chapters, the upbringings of each artist are crucially different. Whereas Mori was from a more creative family and received a Western education, Kimsooja grew up on military bases and stayed in Korea for most of her schooling. Additionally, Korea ten years earlier was in a much different place than Japan in Mori’s time. Mori’s bright anime culture is met with the stillness of Kimsooja wearing all black. Japan was thriving at this time; it was no match for the traditional society of Korea, and its conservative society was dominated by Confucianism. However, both Kimsooja and Mori are discussed regarding their response and participation in globalization and the global art world, mostly because of their placement in the New York City art scene. When Mori was in Japan, a second wave of feminism was founded, and an economic boom was occurring. In Korea during Kimsooja’s time, women were confined to the home and required to learn Confucian virtues at a young age. A Western democratic system developed in Korea after the end of Japanese colonization, which gave women great freedom. I method I used to conduct my research and an important branch of scholarship for my thesis was the historical and sociohistorical feminism in Korea and Japan in the 20th century. Through this method I was able to establish that the Japanese and Korean perspectives towards gender are at odds with the Western understanding of feminism and provide examples in each artist’s work of how these odds are represented. The relationship between feminism and East Asian societies manifests in Mori’s art through her use of ancient religious figures and themes, such as the traditional Tea Ceremony or the story of the Monkey King, and the reconfiguration of such figures and themes to envision her own perception of modern womanhood. For Kimsooja, the traditional practice of meditation is launched into a series in which that practice is publicized, and she is made vulnerable to the public and the world.

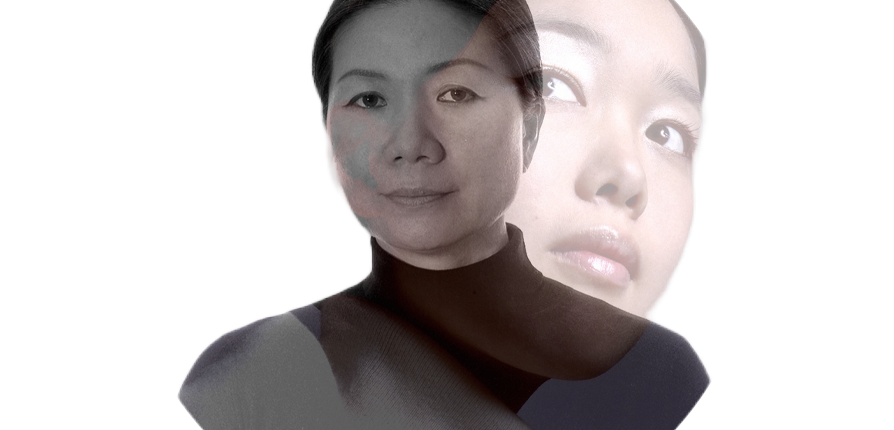

At the center of this thesis is the exploration of self and body. To explore this further, I used the theory of role-playing and its relation to feminist art. As we can see from these pages and the images of their work, Kimsooja and Mori handle femininity differently, starting with their perception of the body. Their different perceptions of the body again circle back to their very different upbringings. Mori has manipulated her body and created a surrogate that invites the gaze of the viewer in to satisfy visual pleasure. She physically transforms into the cyborg or deity to comment on these themes of gender and identity. On the contrary, Kimsooja rejects the gaze, turning her body away from the viewer. Kimsooja’s use of bodily presence influences her performance in a less obvious way than Mori. Where Mori is drawn to role-playing, Kimsooja positions herself in a very matter-of-fact way. Kimsooja’s performance, however, and the role she plays could be viewed as the role of a window or keyhole into other places and cultures. There are no frills to her version of performance and femininity, as there are with Mori. This is undoubtedly due to their separate views of women in their respective countries. Kimsooja’s simpler Korean childhood is again in stark contrast with Mori’s art-family background.

Another key comparison between the two artists is Kimsooja’s use of nature with that of Mori’s elements. Spirituality and nature are important aspects of both artists’ work. The ideas of movement, manifestations, and humanity are all present themes, guiding Mori and Kimsooja to moments of transcendence and enlightenment. After months of looking at these series’, thinking about the connections they might share, and making up questions that could link the two together, I’ve found that the biggest connection they have is the relationships they have with themselves. The idea of self-identity and how they both see themselves so clearly, is an inherently spiritual experience. They both see themselves as part of something greater, as part of enlightenment or nature as a whole. The Needle Woman pierces the fabric, she cuts the human flow, and the universe must pass through the eye of the needle.[173] According to Kimsooja, “being nothing/nothingness and making nothing/nothingness is (my) goal and it is a long process to get there.”[174] For her, both Buddhist monks and artists try to liberate and go beyond themselves.[175] For Mori, the Esoteric Cosmos represents the journey to Enlightenment, the furthest point of detachment and spirituality one can reach, or “nothingness.” Both artists wanted to go beyond themselves, go beyond humanity, and this took understanding self-identity to the furthest level. Kimsooja describes the complete enlightenment and liberation she felt during the Needle Women performances. She was “engaged with the whole picture of the world and people as oneness and totality beyond this stream or ocean of people in the street.”[176] Similarly, Pure Land is a direct reference to Enlightenment and Nirvana. The series, representing each stage of the Buddhist path as conception, ascetic practice, enlightenment, and nirvana, provides transcendence.[177] Mori explains the “circular, mandala-like flow” that the series has.[178] It is not centered on human beings, but on nature.[179] This is similar to the flow of the needle that Kimsooja represents in her own series and the desire to be one with nature.

There is no existing scholarship that brings the two artists together. Mori is paired with other Japanese artists, while Kimsooja is compared to other Korean artists. These series and artists (Mori and Kimsooja) were chosen to explore and analyze art works related to spirituality and self-, female-identity while also considering two separate countries’ traditions. In conclusion, Kimsooja mingles the ideas of feminism and spirituality in Needle Woman to reshape the traditional identity and role of the Korean woman, but with more emphasis on spirituality, than Mori’s femininity. The distinction is how they each envision feminine spirituality in their art.