1889

Celebrating the RepublicGallé first displayed his work at a Universal Exposition in 1889, where his designs were featured in exhibits on both art and industry, in a reflection of the very changes that Gallé and Marx advocated.[1] This simultaneous display made the perfect venue for Gallé to participate and present himself as both an artist and a man of industry. The exposition was also an opportunity for Gallé to convey his own ideas in alignment with the broader themes of the exposition: to commemorate the first republic and to celebrate republican values. Immersed in the colonial propaganda prevalent at the exposition, Gallé himself identified with the discourse of France’s civilizing mission, and saw himself as participating in it, taking the raw materials that were a direct product of colonialism, and improving them into decorative, refined, luxury furniture objects that would help to legitimize his career as an artist. Moreover, Gallé overtly displayed these sentiments of French nationalism and colonialism alongside one another.

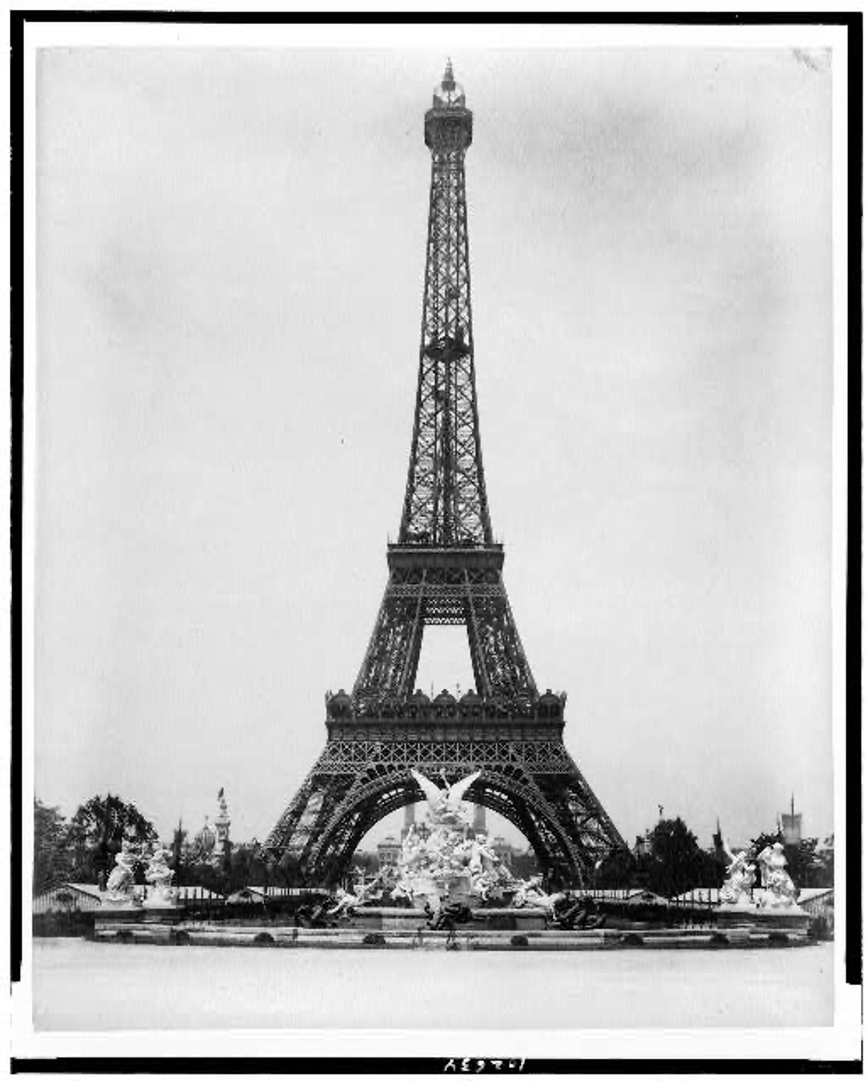

The 1889 Exposition Universelle broadcasted themes of republicanism, recovery, and progress, and they were echoed in the exhibits that populated it. Prior to the 1889 Exposition Universelle, Paris had played host to a succession of universal exhibitions in 1855, 1867 and 1878, that all presented France’s proudest achievements in art and industry for an international audience. The 1889 Exposition was held as a centennial celebration of the storming of the Bastille in 1789, and also as a rebirth of the city still reeling and rebuilding after the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune.[2] It encompassed the Champ de Mars and Palais de Trocadéro, built for the 1878 Exposition, with the newly-built Eiffel Tower at its center (Figure 9). The Eiffel Tower served as a monument to French ingenuity amidst efforts to rebuild the city after the destruction of the Franco-Prussian war and the Paris Commune. In honor of the French Revolution, and the “Declaration for the Rights of Man” that came out of it, the exposition proudly exhibited France’s republican values. Concerned over civil unrest in their own countries as a reaction to the republican themes, several European royal leaders opted not to participate.[3] In short, the 1889 Exposition Universelle was a celebration of French history, culture, progress, and individual liberty.

Despite the tone of republicanism echoed throughout the 1889 Exposition Universelle, the rhetoric of individual liberty and equality for all did not pertain to French subjects living outside of France under colonial rule. Colonialism had been an increasingly common theme at Parisian universal expositions in the second half of the nineteenth century, likely as a response to French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in an effort to regain power.[4] According to Michael D. Brooks, French political leaders toward the end of the century advocated for increasing colonization efforts as a way to “obtain the essential raw materials and manpower needed to regain France’s former glory.”[5] The 1889 Exposition featured a Colonial Exhibition, which, according to Erik Mattie, “recreated dwellings and villages – including inhabitants- plundered from France’s overseas colonies.”[6] In their book, Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire, Nicolas Bancel, and Dominic Thomas argue that the Colonial Exhibition served as a venue for public officials to “transform public indifference, and draw attention to both the necessity and the legitimacy of the colonial project.”[7] Visitors were immersed in propagandistic imagery that displayed spoils of overseas expansion alongside theories of eugenics that positioned the colonies as a tool to be used by France for French success, hoping to encourage visitors to not only support, but to identify with the idea of the French empire.[8]

For the 1889 Exposition Universelle, Gallé presented himself and his work in a way that aligned with the exposition’s combination of art and industry, and in a way that resonated with the exposition’s messaging on colonialism. Gallé submitted notes to the jury that helped to frame these objects in context with one another, particularly focusing on bois des îles and patriotic sentiment. Gallé also wrote about the start of his career as a woodworker, stating that his interest in wood came out of a desire to create an “exotic” wood base for one of his glass pedestals (for example, see Figure 10):

Figure 10: Émile Gallé, Raisins Mystérieux, 1892. Glass bottle with metallic inclusions, opalescent blown glass stopper, carved and tinted pear wood base. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

One day, a lovingly carved vase needed an original support to show its value. Some sort of rare tropical hardwood was needed. I went to a trader of these special species for the first time. I thought I had discovered the Indies and America. What a surprise to see, under the scraper and the wax the drops of amaranth turning to crimson in the sun and the fragrant shavings like petals of rose and violet![9]

This excerpt is indicative of the way in which Gallé prized the idea of exoticism. He desired specifically a “rare tropical hardwood,” or “bois des îles d’une nuance rare,” without having preconceived ideas of what such a wood would look like.[10] Gallé framed his foray into woodworking as a “discovery,” likened it to discovery of the Indies and America, and made clear his preference for bois des îles.[11] Gallé began his “journey of discovery” explicitly seeking exoticism, which clearly led to inspiration, as he began to imagine the different ways he could use the wood and the distinctive effects he could achieve with each variety. Gallé’s use of bois des îles presented him with immense variety in terms of color, grain, pattern, hardness, and hue, but it also allowed him to co-opt France’s civilizing mission for his own gain, taking a wild, raw material and sculpting it into a refined and finished form. However, by the time Gallé obtained the wood or veneer to be used for his projects, the wood no longer resembled itself in its original raw, natural form.[12] Gallé was separated from the source of this raw material by more than distance. The term bois des îles then served as a catch-all that referred to “wood from the islands” in place of noting the precise species of the wood. Often, Gallé did not designate the type of wood he used, instead opting to refer to it as “tropical hardwood.”

Gallé’s ideas about the exoticism of wood were crucial to the way he crafted his own self-image, and so we must keep in mind the idea of self-fashioning with regards to the above excerpt. We can read it as an attempt by Gallé to cultivate his persona as an artist, on a journey of discovery for his art, and an effort to convey this persona to an audience of the jurors that would be examining his work. Gallé’s story of “discovering” exotic woods is likely an embellishment of a much more likely pragmatic truth that Gallé saw a business opportunity to meet demand from an influx of immigrants from the recently-seized Alsace-Lorraine region in need of home furnishings. It is also of note that exotic wood was also notoriously difficult to work with on account of its density, and so in choosing to flaunt his use of it, Gallé was signaling his mastery of woodworking.[13] Nonetheless, by emphasizing this moment of inspiration upon seeing these exotic woods for the first time, Gallé intrinsically tied his continued interest in woodwork to the rarity of the materials, and foregrounded this journey as an important part of his practice.

Gallé’s notes to the jury, painstakingly detailed his factory as a way to create legitimacy for himself as a woodworker, and to establish his reputation as a man of modern industry. He described the layout of the factory, the machines and tools they used in it, and even the way in which supervisors worked to promote efficiency. Gallé presented his factory as a state-of-the-art center for production. He also described the bon marché or “inexpensive” furniture intended for clients of discerning taste with a more modest budget. Among these were pedestal tables and serving tables, made of high-quality, but common wood that allowed for the reduction in price. Gallé explained that though quality was not sacrificed, simpler and more efficient techniques were employed in order to put “interesting objects, which carry the signs of art and the feeling of craftsmen in love with their trade, within the reach of the average person’s means.”[14] Despite this emphasis on quality despite the lowered price point, Gallé distinguished his bon marché furniture from his meubles en luxe, or “luxury furniture items,” and displayed them separately.

In order to enter Gallé’s meubles en luxe exhibit in the exposition, one had to pass through an elaborately carved, decorative partition that physically and thematically framed the exhibit. Though there are no surviving photographs of the partition, entitled Bois des Îles, Gallé described it in detail in his notes to the jury. The extremely ornate work featured a variety of bois des îles: amaranth wood, lakeside oak, mahogany, and rosewood, among others. The wood was carved into various tropical vegetation, fruits, and foliage, and was inlaid with semi-precious stones, including rubies, amethysts, and emeralds, that elevated the luxurious quality of the exotic woods even further.[15] In his notes to the jury, Gallé wrote that “the engravings on the panels allude to the tropical wood trade,” making it clear that he was aware of the process by which these woods came to him.[16] The prominent placement of the decorative partition at the entrance to Gallé’s exhibit situated his seventeen pieces of meubles en luxe within the context of bois des îles and the tropical wood trade, a product of French colonialism.

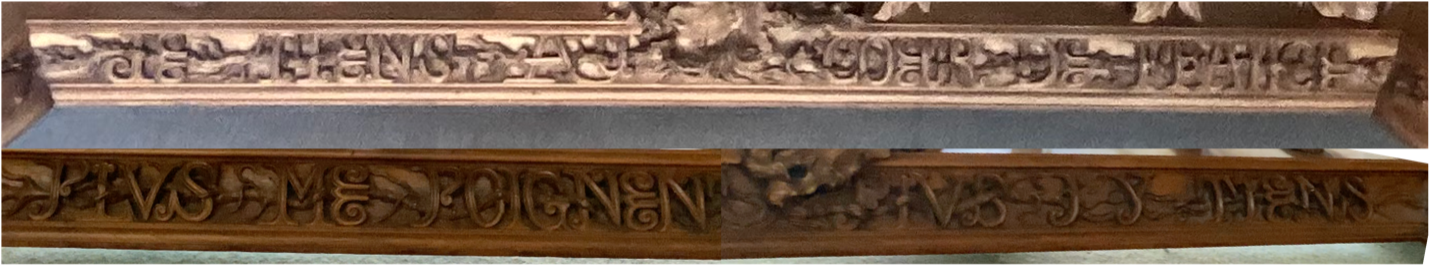

Gallé also provided descriptions of several of the objects on display that made clear the way he wanted them to be seen, for example as a patriotic nationalistic object in the case of Le Rhin Table (1889, Figures 11 and 12). This shows that in addition to natural phenomena, Gallé took inspiration from contemporary events. As Dandona argued, Le Rhin considered conceptions of “Frenchness” that conveyed his steadfast republicanism and patriotism through their use of local woods, depictions of native flora and fauna, and even through literary quotations that were embedded into the marquetry.[17] At over seven feet in length, the large table features an intricate marquetry scene depicting a moment in the battle between Gauls and the Teutons in which the Gauls defend their land from invasion (Figure 12). Gallé’s experience of the Franco-Prussian War and Germany’s annexation of Alsace-Lorraine informed his socio-political ideologies and inspired the themes he incorporated into his art.[18] Gallé’s notes to the jury referenced a text by Tacitus: “The whole of Germania is separated from the Galli by the River Rhine.” This quotation shows that the battle scene serves as an allegory for the German seizure of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871, following the Franco-Prussian War in which Gallé fought for the French army.[19] The table’s base features hand-carved Lorrainaise heraldic birds and thistle native to the Lorraine region, as well as allegorical vegetation signaling fidelity, royalty, and love (Figure 13).[20] The bottom cross-beam features a carved inscription that spans both sides: “I am fond of the heart of France // The more they afflict me, the more I am fond of it” (Figure 14). This table proudly proclaimed Gallé’s unwavering patriotism and sought to call its viewers to action in a celebration of France, in keeping with the broader themes of the 1889 exhibition. According to Dandona, the Rhin operated as Gallé’s centerpiece across all major exhibitions from the table’s completion for the 1889 Exposition Universelle until Gallé’s death in 1904, centering issues of “Frenchness” and luxury furniture as essential to Gallé’s work.[21] For Gallé, works like Le Rhin were not only beautiful, but also conveyed some deeper meaning, in much the same way that contemporary audiences expected of fine art.

Considering Le Rhin in relation to the Bois des Îles decorative partition prompts one to consider Gallé’s own ideologies, especially in the context of the 1889 Exposition Universelle’s celebration of culture and heritage in the wake of the tragedy of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. It is clear that Gallé’s table is also a celebration of pride in French culture and heritage in the aftermath of the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine, designed to sew patriotism among its viewers. The table acts as a visual representation of Gallé’s republicanism and intense nationalism.

[1]. Dandona, Nature and the Nation, 10.

[2]. Erik Mattie, World’s Fairs (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 76-7.

[3]. Mattie, World’s Fairs, 76-7.

[4]. Pascal Blanchard, Sandrine Lemaire, Nicolas Bancel, and Dominic Thomas, Colonial Culture in France Since the Revolution (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2014), 91; Michael D. Brooks, “Civilizing the Metropole: The Role of the 1889 Parisian Universal Exposition’s Colonial Exhibits in Creating Greater France,” The University of Central Florida Undergraduate Research Journal 6.2 (July 24, 2013), 71.

[5]. Brooks, “Civilizing the Metropole,” 73.

[6]. Mattie, World’s Fairs, 82.

[7]. Blanchard et al., Colonial Culture in France Since the Revolution, 90.

[8]. Rebecca Peabody, Steven Nelson, and Dominic Thomas, Visualizing Empire: Africa, Europe, and the Politics of Representation (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2021), 1; Peabody et. al., Visualizing Empire, 87.

[9]. Translated text from from Duncan and De Bartha, Gallé Furniture, 26; for original, see Émile Gallé, Écrits pour l’Art, 355; for the purposes of this project, I am defining “exotic” as the phenomenon in which individuals project their own fantasies their perceived “other.”

[10]. Gallé, Écrits pour l’Art, 355.

[11]. Original text from Gallé, Ecrits sur l’Art, 355; Translation from Duncan and De Bartha, Gallé Furniture, 26.

[12]. Duncan and de Bartha, Gallé Furniture, 15.

[13]. Sextro, “Materials of Empire,” 44.

[14]. Original text from Gallé, Ecrits sur l’Art, 365; Translation from Duncan and De Bartha, Gallé Furniture, 29.

[15]. Gallé, Écrits pour l’Art, 361-62.

[16]. Original text from Gallé, Ecrits sur l’Art, 362; Translation from Duncan and De Bartha, Gallé Furniture, 28.

[17]. Dandona, Nature and the Nation, 7-10.

[18]. Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-De-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology, and Style, 230.

[19]. Gallé, Écrits pour l’Art, 371.

[20]. Gallé, Écrits pour l’Art, 371.

[21]. Dandona, Nature and the Nation, 10.