Liberation, Limitation, and the Tenpo Reforms

Limitation & Liberation

Whether it was the everyday haori styles or festival attire, every example of female crossdressing in the period utilized a strategic combination of masculine and feminine sartorial markers. The Tokugawa period is marked by a particularly intense sartorial system. Gregory Pflugfelder wrote, “It is no exaggeration to say that for early modern Japanese such visible markers of identity constituted the primary signifier of belonging to a given social category.”[1] How a person fashioned himself or herself communicated everything others needed to know about them. The Tokugawa government was known for its intense sumptuary laws that helped uphold this connection between clothing and social belonging. For the state, this was a tool to quickly identify its citizens and police them accordingly.[2] Within this system that dictated that what you wore represented who you were, geisha’s choice of gender play was socially significant. So significant that the government should have been more invested in getting rid of the practice. But as explained above, geisha was not really moving beyond their station. Dressing like their wakashu counterparts in the red-light district was a more horizontal than vertical social move. It did not represent a challenge to the social strata above them.

This androgynous play made cross-dressed women and their image unique from that of the Kabuki onnagata actors, whose goal was to perform the perfect simulation of womanhood on stage. Onnagata could not let the lines blur; their illusion had to be seamless to put on a convincing performance. This complete crossover of the gender boundary was allowed because onnagata were adult men, and it was completely performative, isolated to the stage. Even if the social status of actors was low, they were still fundamentally above women and wakashu. The patriarchal order was not as concerned with policing them since they were the people the order was constructed to uplift. Also, as their perfect illusion was a performance, they might continue it off the stage to entertain patrons, but the illusion was over outside the theater. Many onnagata actors still fulfilled their broader societal roles by taking wives and having children, thus continuing their family lineage.

The same expectation of performance held true for geisha. Once the festival day was done or they retired from the district, the gender play was over. It only existed for the sake of spectacle or as the archetype of bijinga. These limitations liberated geisha from the paternalistic eye of the government. If they and their gender-ambivalent performance stayed within the literal and metaphorical walls of the entertainment world, then the play could go on. But a fundamental shift in the publishing industry would mark the end of the government’s tolerance.

While the artist Kunisada would create some of his iki town geisha images in pin-up style album collections like Thirty-two Physiognomic Types of the Modern World, many more appeared as illustrations in the literary works of his friend and collaborator Ryutei Tanehiko. Tanehiko’s genre was Ninjoban (“books about human feeling”), an emerging genre that, in familiar with other books at the time, featured vibrant illustrations by Ukiyo-e artists. Ninjoban stories were concerned with human emotion and falling in love, focusing on the lives of female musicians, geisha, and other professional women. The main reader base of these books was women, so in the Ka’sei eras, the works of Kunisada and other printmakers were gaining a new growing viewership of women and children. This led the Ukiyo-e illustrators to become household names among married women, mothers, and daughters. Previously these groups of women didn’t associate with these artists’ works because of social propriety.[3]

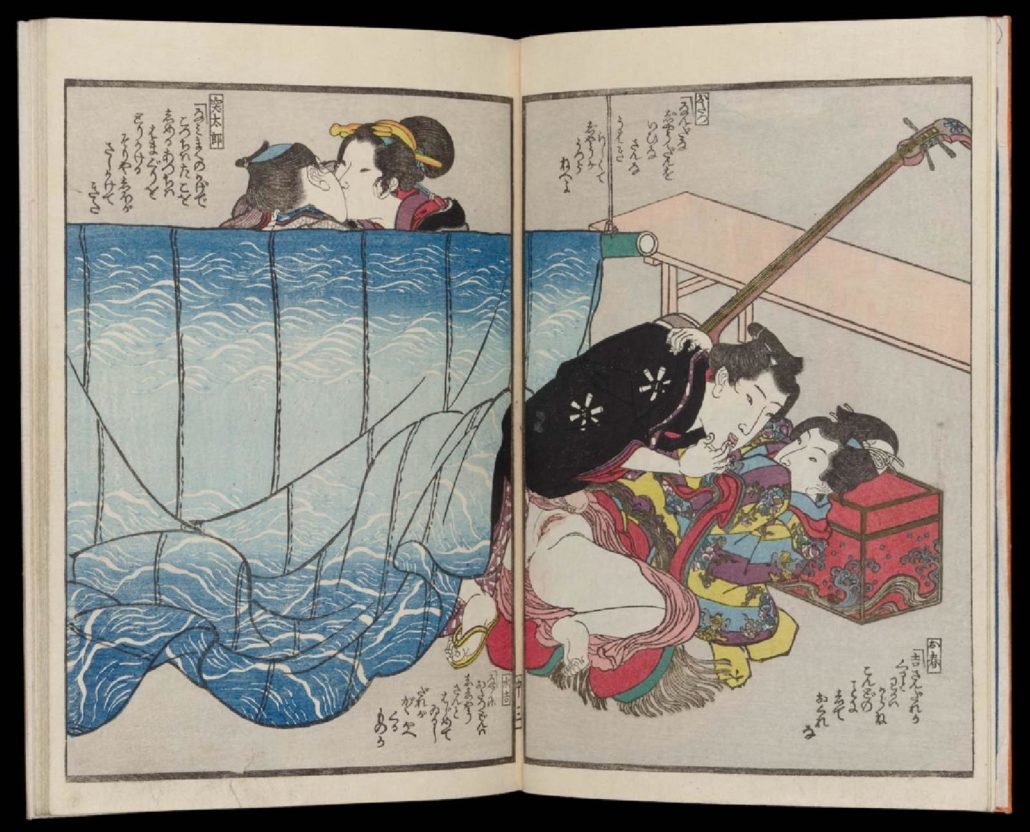

In Ninjoban, women played a pivotal role in high romance and melodrama stories. In the stylish geisha, women found an icon for fashion and behavior. This kind of aspirational identification was likely intended by the writers and printmakers. Buying, selling, and chasing the next fashionable thing was the culture. The prints visualized the attention Ninjoban prose lavished on descriptions of clothing and fashionable items. Amongst these fashionable trends was cross-dressing, as showcased in one of Ryutei Tanehiko and Kunisada’s collaborations from 1836, entitled Shunjô gidan mizuagechô (Figure 8.) In the scene, the main character of the story has succeeded in bringing her client and lover to bed on the night of a festival, as evidenced by the colorful patterns of her clothing. The outfit she wears also appears to be a variation of the lion dance costume, so her moment of triumph comes when she cross-dressed and is at her most charming. Crossdressing also seems to be a part of her everyday persona based on the permanent shaved patch of hair on her head. Narratives like this gave female readers a perfect literary and visual guide on how they should dress and act to be the most charming. The women of Ninjoban stories were not always perfect but were proactive, and their attractive persona became linked to their masculine garb.

Townswomen began to emulate this style to achieve similar personal fulfillment. Yoshiwara courtesans had long been the icons of style for women in the capital. Now that geisha was the new trend. Townswomen naturally moved their aspirations onto them. But these emulations only happened with pushback. Townswomen of respectable samurai and merchant families sporting shaved patches, haori jackets, and masculine mannerisms to emulate their favorite geisha heroines garnered the government’s notice. This was a step too far, and to bring their populace back into their easily governable boundaries, the government organized a crackdown. The first on the chopping block were the cross-dressed geisha and the multicolored record of their practice in print.

The Purge and After

Immediately following the Ka’sei eras was the Tenpo (1830-1844). In the final years of that era, following the death of the shogun, a series of devastating natural disasters, and violent city gang wars, strict reforms were instituted. To address the social and political stresses of the past decade, the government decided to clean up the entertainment industry. Sex workers in unlicensed districts, like Fukagawa, were arrested in mass. Either these women were told to go home and find other professions, or they were transferred to the licensed Yoshiwara district. By the end of this purge, 4,181 unlicensed sex workers were arrested, and 2,165 were moved to Yoshiwara.[4] Along with this mass crackdown on illegal brothels, the government also banned all Ukiyo-e prints of kabuki actors, beautiful women, and erotica. Well-known authors from the Ninjoban genre, such as Ryutei Tanehiko and Tamenaga Shunsei, were publicly reprimanded and had copies of their books burned.[5] This massive ban and subsequent destruction are why very few images have survived from the Tenpo era. Cross-dressing women in print dating to the reform period are conspicuously scarce.

These reforms sought to reestablish a separation between the lascivious entertainment world and respectable everyday life. This separation was previously represented by the walled district of Yoshiwara. With new, more popular pleasure quarters forming around the city without government oversight, the clearly defined lines between upright citizens and low-class entertainers blurred. The isolation of Yoshiwara was meant to function as what Richard Reitan described as “gendered and moral spaces that facilitated the conceptualization of “female respectability” by spatially defining respectability’s other.”[6] Yoshiwara provided an essential foil to the proper Japanese women of the upper and middle classes. For the feudal government, the only thing good wives and daughters should learn from Yoshiwara was who not to be. Confucian principles did not have the same cultural hold among the Japanese public the way they did at every level of Chinese society, but it was the doctrine that government officials supported and saw themselves as upholding. Japanese adaptions of women’s didactic texts from China, including the Onna Daigaku and Onna Imagawa, had the same rhetoric but conspicuously lacked the central idea that “men pursue their duties without, while women govern within.”[7] It would eventually be included, but the Chinese Confucian conception of gendered space would always have a weak grip on Edo society. Instead, Chino Kaori’s discussion of gender in Japanese art provides a more native Japanese approach to the gendering and policing of space. The two main distinctions of Japanese art originating in the medieval period were Kara, or Chinese style, and Yamato, or Japanese style. Kara was identified as the masculine style, while Yamato was feminine. Kara was public and outward, while Yamato was private and intimate, a unique version of the feminine. It “was oppressive when those who could not understand what was ‘courtly, refined, and elegant’ were labeled ‘barbarian and vulgar country bumpkins.’”[8] It also gave the government more reason to police Japanese women because if Japanese identity was linked to the feminine, then it was all the more critical that women, as the embodiment of the feminine, only lived the purest, most upright lives.[9] In the private space, Japanese identity must be protected: woman’s place had to be within, and man’s place was without. Gender-ambivalent aesthetics that encouraged women to transgress, and explore queer possibilities of expression, put Japan’s essential identity at risk. It was too great a challenge to the Tokugawa order.

The sex worker was left out of this structure and as stated earlier, became an important example for defining proper Japanese womanhood. They were loved and admired in times of abundance, but when social conditions dampened, they were the first to be victimized by governmental reform. Their visibility made them into a dog whistle for societal woes. This became particularly true in the nineteenth century when, as Amy Stanley describes it:

…prostitutes began to provoke nightmares about the decaying countryside, the failing state, and the crumbling family. They held up a mirror that turned those benevolent governors into despots, generous patrons into irresponsible hedonists, patriarchs into immoral child sellers, and businessmen into parasites. Discomfited by this reflection, men blamed women for showing them what they preferred not to see.[10]

The sex worker was not a woman who stayed within. Just being visible by way of unwalled districts and popular prints, she exemplified a form of female liberation that was appealingly packaged. When her viewers were men, she was the stand-in for a fantasy, a strange but salacious parody of everyday life, or the perfect romantic tryst for the urban sophisticate. But when her fellow women took notice, the geisha became a model for the potential to expand the possibilities of personal expression. Her image fulfilled women’s desires to be fashionable, well-read, and active agents in their own lives.

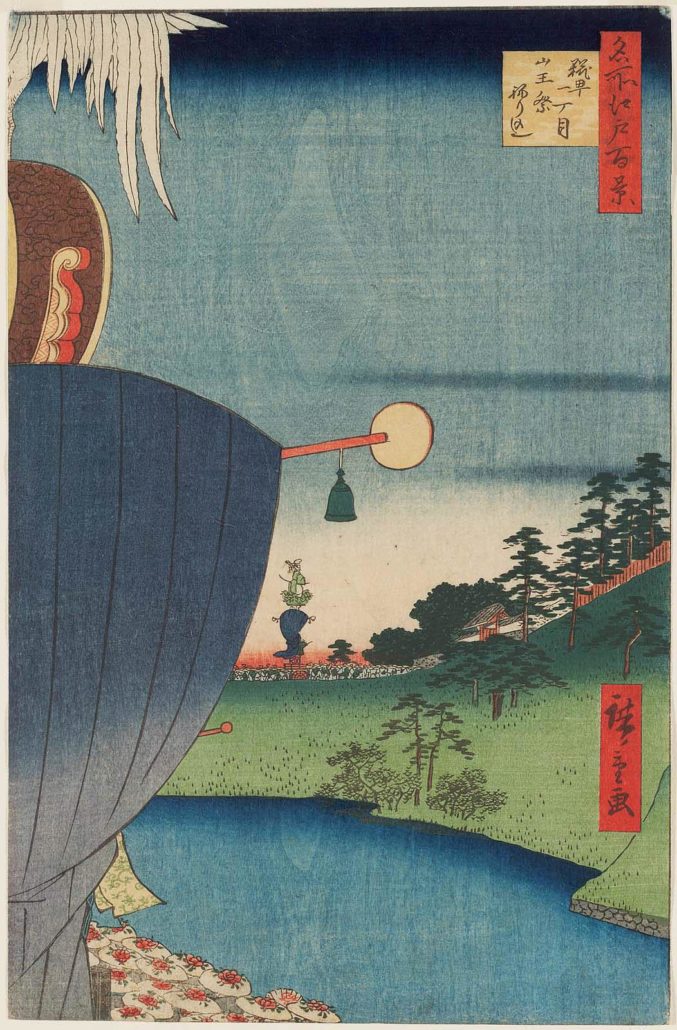

With such historical context in mind, it now becomes clear that Figure 2 is unique because it bears the scars of the Tempo Reform. Bijinga was no longer allowed in its purest, most erotic forms, but artists could find clever ways to continue using the subject matter people loved. The functional purpose of the Thirty-six Views of the Pride of Edo was to show the wonders of the Shogun’s capital. The print in question represents the biannual Sanno Festival, one of the three great festivals of Edo, along with the Kanda and Fukagawa. This choice of subject matter borrows more from the landscape or views genre because a festival was most associated with the place it was held. A good example of this more traditional depiction is Hiroshige I’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856) in the print “Sanno Festival Procession at Kojimachi 1-chome” (Figure 9). Hiroshige focused on the long procession of the festival cutting through the landscape. No one group of performers is clearly identifiable, but instead, the parade is a large, flamboyantly colored mass creating a festive mood in the scene. It is worth noting that in the foreground, a large group of people wear the hanagasa hats seen on the young girl’s back in the 1864 print. So even though figural representation is not the subject of Hiroshige’s print, the tekomai still appears in close association with the festival.

Hiroshige II and Kunisada have departed from this more traditional treatment by foregrounding the two curious yet pleasant-looking young women dressed in men’s clothing. Including prominent female figures is a constant throughout the series, making the album read more like bijinga than landscapes. But the print also does not follow the more bijinga heavy compositions that have survived in the years after the reforms. Continuing with depictions of the Sanno festival, an earlier print by Kunisada from One Hundred Beautiful Women at the Celebrated Places in Edo titled “Sanno Shrine” (Figure 10) also features a geisha in tekomai as a shorthand for the festival. The landscape indicating the affiliated shrine is regulated to a small frame in the upper left corner of the print. This way, the viewer’s attention is entirely on the woman and her beautifully dressed appearance, but by presenting the subject as the festival and not the woman, it can pass censors despite this composition. Landscape and figures are more fully integrated into the Kunisada, Hiroshige II collaboration.

For this reason, the print represents a more sophisticated negotiation than images like the Kunisada mentioned above. The women are more naturalistically incorporated into the landscape and given equal importance to the place or product indicated in the print title. They use this more fully formed landscape to create a purpose that does not mitigate the eroticism of the print but puts it in line with the new values of the state. Kunisada and Hiroshige have returned the cross-dressed geisha to her confine. The sturdy pillar separates her from respectability.

The cross-dressed woman did not go away completely. Instead, she returned to the position of festival spectacle as seen in the Eizan print. The subversive iki archetypes were abandoned, rarely appearing in any depictions after the Tenpo reforms. The tekomai, became a subject popular in the years following the reforms. Before he collaborates with Hiroshige II, Kunisada would illustrate the subject in his 1857 series mentioned earlier and in a Kanda Festival triptych from 1845. Hiroshige I also included it as one of his many Tokaido road series in print “Yokkaichi” From 1849. A contributing factor to the reemergence of these images and Ukiyo-e generally, even after the violent ban and burning of printed material, was that the Tenpo reforms were unsuccessful in helping the Tokugawa government regain the control they once had over Japan. In fact, the decades following the reforms would be a steady decline. The attention of the shogunate was pulled to the outer provinces that fractured and started to pledge allegiance to the emperor instead of the Shogun. Tokugawa Japan officially ended on January 3, 1868, when the pro-imperial forces won the brutal civil war, and the Meiji Emperor took control. This event, the Meiji Restoration, would push Japan into the modern era.

[1] Gregory Pflugfelder, “The Nation-State, the Age/Gender System, and the Reconstitution of Erotic Desire in Nineteenth Century Japan.” The Journal of Asian Studies 71, no.4 (November 2012): 963.

[2] Pflugfelder, “The Nation-State”, 963.

[3] Izzard & Schaap, Kunisada. 16.

[4] Cecilia Segawa Siegle, Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993,) 210.

[5] Siegle, Yoshiwara, 210.

[6] Richard Reitan. “Claiming Personality: Reassessing the Dangers of the ‘New Woman’ in Early Taishō Japan.” Positions: East Asia cultures critique 19, no. 1 (2011): 94.

[7] Elizabeth Lillehoj. “Properly Female: Illustrated Books of Morals for Women in Japan” in Women, Gender, and Art, c. 1500-1900. ed. Melia Belli Bose. 246.

[8] Kaori Chino. “Gender in Japanese Art.” In Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field, edited by Joshua S. Mostow, Norman Bryson, and Maribeth Graybill, (University of Hawai’i Press, 2003,) 31.

[9] Kaori, “Gender in Japanese art,” 32.

[10] Stanley, Selling Women, 7-8.