Urban Edo & Iki Ideals

Spectacle in the Market of Desire

Moving back to decades before the 1864 print, we can examine the urban cultural context that birthed the cross-dressing geisha. The city of Edo had reached 1,000,000 by 1721, making it the largest metropolis in the world at the time.[1] By the nineteenth century, Edo was a massive city housing many industries for visitors and citizens to experience.[2] The competition amongst various shop owners grew as they all raced to fulfill the desires of the growing urban consumer population. More options meant that consumers needed to know where and how they could have their desires fulfilled. David Pollack identified this as the “economy of desire” that defined the city of Edo and dictated its various socio-cultural practices and representations.[3] Through near ubiquitous advertising, no corner of Edo culture was left untouched: visual art, literature, and theater all took part in the market. Poets doubled as copywriters for well-known businesses, and kabuki actors would advertise for sponsors during shows.[4] Ukiyo-e artists also participated, creating sumptuous visual guides for what sites to see, what products to buy, and which beautiful women to meet.[5] This is where the various subjects of Ukiyo-e emerged, and each one fulfilled a consumer demand or assisted the industry in promoting itself. Ukiyo-e became more than a record of Edo culture; it was an advertisement of that culture.

In the early decades of this market, images of women cross-dressing were considered a kind of Bijinga, which, coming out of the eighteenth century, exclusively depicted the women of the licensed red-light district, Yoshiwara. Initially formed in the seventeenth century, Yoshiwara comprised 20 walled-in acres in Asakusa, which was geographically set apart from the rest of the city.[6] Yoshiwara became a self-contained, isolated world with society and culture all its own. The district offered men a place to indulge in romance not inherent to marriage in the feudal period. Marriages were based on legal and economic obligations. Yoshiwara was conceived as an inverse of the everyday world. Its rituals and events were all designed to parody the rites of marriage, separating the pursuits of pleasure from the reproductive pursuits expected of the wife.[7] The courtesans and geisha of Yoshiwara instead offered “fantasies of tenderness and passion” that would become the idealized romances in books and plays.[8] In this earlier Yoshiwara-centric Bijinga, cross-dressed women predominately appeared in the context of the Niwaka festival. This festival was held in the 8th month of the lunar calendar and honored Kurosuke Inari, the patron god of Yoshiwara. The occasion featured a variety of musical, dance, and theatrical performances where courtesans and geisha were cross-dressed. They put on productions of popular kabuki shows and performed lion dances with full female troupes.

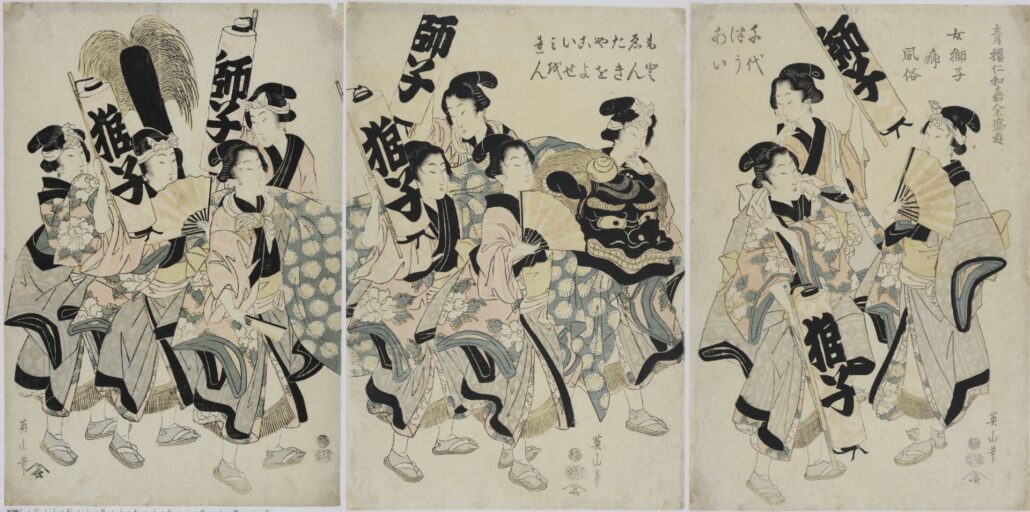

Kikukawa Eizan’s Niwaka Festival at Shin-Yoshiwara (Figure 5) from 1811 to 1813 depicts one such lion dance troupe and exemplifies the look and function of images from this early period. This image entirely focuses on the female subjects using a simple composition with minimal background elements. Eizan gave great attention to the patterns and layers of the geisha’s performance outfits, the lanterns with “lion” written on them to announce their performance, and the list of their names along the upper edge crossing the right and center panels. Their names were significant since this print had to also function as an advertisement for these women’s services. Potential clients could see the women’s names on the print and subsequently find them in Yoshiwara. This context established in Eizan’s print created a limited time and place for cross-dressing. That rarity allowed for an understanding of the cross-dressed woman as a spectacle. She was simply a part of the grandeur of the festival that can be advertised to would-be attendees and patrons.

An Image of the lion dance or shishimai also reveals another aspect of the spectacle. This dance was typically performed by men in its various iterations across Japan. Thus, it would have been a curious and almost humorous sight to see a group of women performing it instead. The lion dance in Eizan’s print and the Tekomai in Kunisada’s are a kind of parody or caricature. While reminiscent of the usual male parade members, the female performers added a unique twist. Placing women in the roles of men was a common subject in Bijinga; typically, it took the form of depicting famous male historical figures as beautiful women. These images were considered equal parts pleasing and comic.

Emerging Iki Archetypes

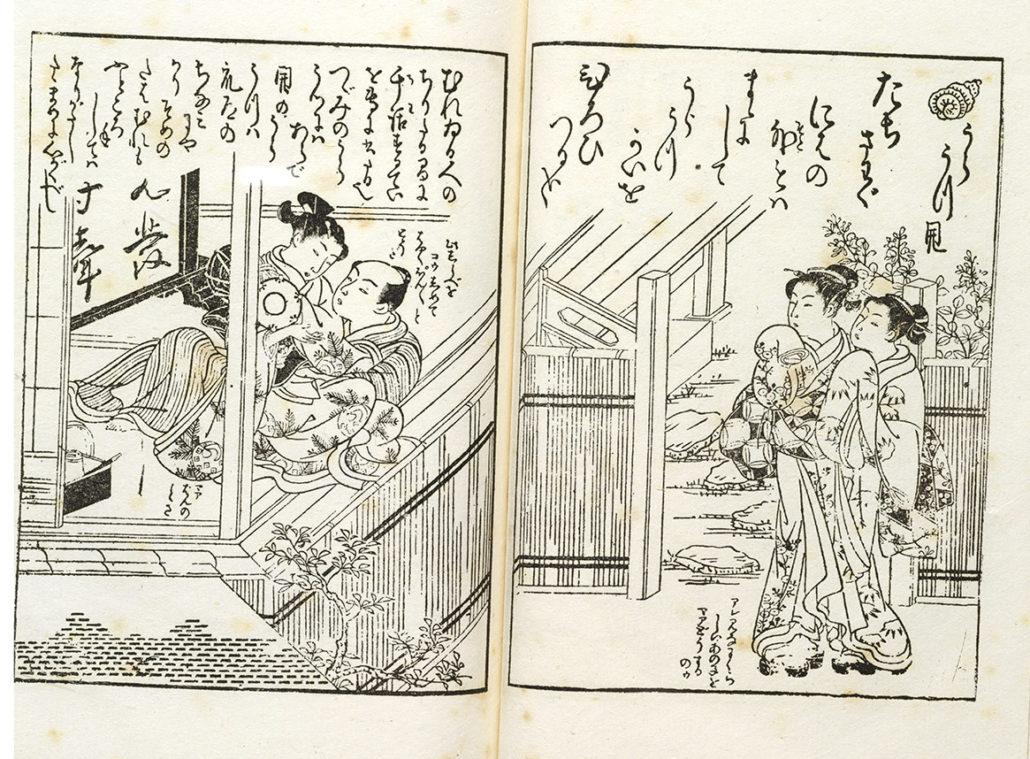

Eizan’s choice in his print to picture geisha instead of courtesans was a savvy and intentional one. In the nineteenth century, the men of Edo had begun to shift their tastes away from the spectacle of Yoshiwara and its opulent courtesans. Instead, they directed their interest and business to the geisha and the unlicensed quarters. Geisha was originally a male profession and was used to describe many musicians and performers working alongside the courtesans in the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter. The broad definition of geisha would carry over when the title was attached to professional female entertainers. There were various types of geisha: ones who specialized in acrobatics, those who played the string instrument shamisen to attract business customers, and others who offered sexual services like their courtesan counterparts. It was the geisha who began as odoriko or dancing girls that would eventually become known as town geisha who catered to sophisticated urban clients in the district of Fukagawa.[9] The prosperity of Yoshiwara started to wane as the relaxation of government oversight and the subsequent diversification of entertainment sources in Edo occurred in the Bunka and Bunsei eras (between 1804-1830).[10] Yoshiwara was not only at the periphery of the metropolis geographically; it had now been pushed from the spotlight of entertainment culture (Figure 6).

Utagawa Kunisada provided an excellent example of these new town geisha in his print “The Competitive Type” from the bijinga series Thirty-two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World from the 1820s (Figure 7). A geisha sits amongst her blankets, leaning forward, presumably conversing with an unseen client. In her hand is a bundle of multipurpose paper, but it is unclear how she plans to use it.[11] She sports a high shimada hairstyle and layers of kimono made of cherry blossom and maple leaf motifs, plaid, and shibari dye fabrics in muted tones.[12] Her clothing would be considered highly fashionable and masculine. Most strikingly, she has a patch of hair behind her forelocks shaved, a cut typically sported by young men. This new cross-dressed everyday attire worn by town geisha matches well with the character assigned to her by the artist Kunisada. Unlike the named geisha in Eizan’s print, Kunisada instead presents a type.

While the title of this print has been translated as “the Competitive type,” the original Japanese title Tatehiki-so can also be translated as proud or prideful. Its third, more complex meaning is a term that describes a woman who takes the initiative to pay on behalf of a man, particularly when a geisha pays on behalf of her client.[13] The term Tatehiki-so, in all its possible translations, describes a woman with a traditionally masculine demeanor. Competitive, prideful, and ready to take the initiative, Kunisada has created an archetype of the town geisha. In this form, she would become the representative bijin (beautiful woman) of the Bunka and Bunsei eras (1804-1830.) The Fukagawa geisha appealed to Edo urbanites because this new masculine play made their encounters more casual.According to Izzard and Schaap, the geisha presented themselves with “straightforward manners, no-nonsense conversation, and simple taste.”[14] This differed from the highly choreographed interactions required for meeting with Yoshiwara courtesans. High-end courtesans required guests to negotiate the terms of their meeting before they were allowed to enter the brothel and interact with them. On the other hand, geisha met clients after they entered the building and enjoyed themselves, creating a less stifling atmosphere.[15]

This begs the question of why these town geisha who dressed and acted as men appealed to male Edo urbanites. The answer is a fashionable aesthetic principle called iki. Iki was born from the culture of Yoshiwara and was propagated by the urban elites who frequented the district.[16] It originated in the eighteenth century. It was firmly rooted in the extravagantly dressed courtesan and the meticulously choreographed game of push and pull she would play with her clients. The aesthetic was reliant on the tension of romantic relations. The beauty of iki was in the feeling of sitting on the edge of getting what you want. It was a game of who fell first. This aesthetic created the perfect consumer, constantly chasing potential. They were wealthy, educated men obsessed with desires never fulfilled. To feed the tastes of clients, women of the pleasure quarter took up the character of iki and performed its three central characteristics: hari, a gallant straightforward demeanor that “resisted all compromise, conciliation, and undue social adroitness;” bitai, charm and flirtatiousness, and akanuke, an unpretentious familiarity with all aspects of life.[17] Iki became so crucial to the entertainment world and the “economy of desire” that eighteenth-century brothel owners did everything possible to cultivate and push their courtesans to be more iki.[18] But iki would become most influential when its foremost practitioners went from the Yoshiwara courtesan to the Fukagawa town geisha. More than the audacious and over-decadent courtesan, the geisha’s unfussy persona better matched the characteristics of iki.

So far, the set-up of iki has been heteronormative: a charming woman possessing all the suitable characteristics attracts a man with the proper sophistication to appreciate those characteristics. In reality, geisha were not the only providers of iki performance in the red-light districts. There is good reason to believe that iki was never an aesthetic about binary genders and heterosexual romance. Joshua Mostow challenged the conception of iki ever being heterosexually coded, a concept popularized by Kuki Shuzo’s The Structure of “Iki” in 1930. Mostow asserted:

The erotic allure of iki is, according to this [Kuki’s] definition, limited to heterosexuality. This is very strange for two reasons. Male-male sex and homosexual prostitution was commonplace in the Tokugawa period. By some estimates, even as late as 1800, a quarter of all prostitutes were male. Limiting the concept of coquetries to heterosexual encounters would have made no sense to someone of the Bunka-Bunsei eras.[19]

Indeed, young men referred to as wakashu made up a significant part of the red-light district and theatrical world. Wakashu could be considered a third gender in the gender/sex system of the Tokugawa period because, until they came of age, they were not considered truly men. In the grammar of sexual and romantic desire, women and wakashu occupied similar positions as objects of male desire.[20] The wakashu, along with young women, represented an ideal of beauty based on the ephemerality of their youth. Young women could still be considered bijin when they came of age, but the wakashu lost his appeal once he shaved off his forelocks and officially

became a man. So, the focus on the wakashu was intense among urban elites, and many saw cultivating a relationship with a beautiful wakashu as a mark of a man’s sophistication.[21] It stands to reason then that the wakashu would serve as a source for the cross-dressing of the town geisha. The geisha intentionally played into the appeal of the wakashu to attract her clients and compete with the male prostitutes that shared space with them in the red-light district.

But if the wakashu were the model for the geisha’s masculinity, they never emulated “real” masculinity; they performed androgyny. Wakashu were not yet men; even if their biological sex was the same as older men, their gender and status in a relationship were almost equal to that of women. Geisha in hakama, sporting shaved heads, and forelocks, were still cross-dressing but with a gender identity that was equal to them in status and still below the men at the top of the social order. Again, like in the performative spectacle of Eizan’s print, androgyny becomes another limitation of the cross-dressed woman’s transgressive potential. But while performance and androgyny read as limitations on paper and print, in the real world, they acted as liberators to the living women partaking in practice.

[1] Andrew Gordon. A Modern History of Japan: from Tokugawa Times to the Present. 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.)

[2] The urban culture depicted in Ukiyo-e formed between the late seventeenth and eighteenth century and by 1721 Ukiyo-e experienced significant technical developments in this period, most notably in the 1760s when printmakers would utilize a new form of polychromatic printing that would make it possible to create complex and sumptuous images.

[3] David Pollack. “Marketing Desire: Advertising and Sexuality in Edo Literature, Drama, and Art.” In Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field, edited by Joshua S. Mostow, Norman Bryson, and Maribeth Graybill, (University of Hawai’i Press, 2003,) 72.

[4] Pollack, “Marketing Desire,” 75 & 83

[5] Pollack, “Marketing Desire,” 79

[6] Gary Hickey, Beauty, and Desire in Edo Period Japan, (Canberra, ACT: National Gallery of Australia, 1998,) 25.

[7] Amy Stanley, Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012,) 53.

[8] Julie Nelson Davis, Utamaro and the Spectacle of Beauty. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007,) 116.

[9] Liza Crihfield Dalby, Geisha. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983,) 57.

[10] Unlicensed sex work districts called okabasho began to form in central neighborhoods of Edo. The most prominent of which was Fukagawa, located near Eitai temple and Hachiman shrine. The isolated location of Yoshiwara was now becoming a major detriment to its ability to attract clients. Traveling to the outer reaches of the city was unattractive compared to the easy access Fukagawa and other unlicensed districts offered. Besides location Fukagawa was also home to Town Geisha, a new group of performers that worked predominantly out of teahouse and had begun to take over the spotlight from the high-class courtesans of Yoshiwara. Stanley, Selling Women, 53.

[11] Sebastian Izzard. Kunisada’s World. (New York: Japan Society, in collaboration with Ukiyo-e Society of America, 1993,) 17.

[12] Izzard, Kunisada’s world, 17.

[13] Goo Online Dictionary https://dictionary.goo.ne.jp/word/%E7%AB%8B%E3%81%A6%E5%BC%95%E3%81%8D/

[14] Sebastian Izzard & Robert Schaap, Kunisada: Imaging Drama and Beauty, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Hotei Publishing, 2016,) 17.

[15] Izzard & Schaap, Kunisada, 17.

[16] For this discussion of iki I will mostly be using the understanding elaborated by Nishiyama Matsunosuke which constitutes a good summation of several nineteenth and early twentieth century discussions. There have been more contemporary discussions by philosophers of aesthetics but as this is not an exhaustive study of Iki I have opted for Nishiyama more foundational and socio-historically grounded discussion.

[17] An iki woman’s counterpart was the character of the tsu. Roughly translating to the connoisseur, the tsu was a dandy who frequented the pleasure quarters, theaters, and restaurants of the city. He was a good judge of character who never spoke pretentiously or acted narrow-mindedly. He was well versed in performance like the iki courtesan and played his character within the rules of the game. Matsunosuke, Edo Culture, 54, 55, 59

[18] A notable example of this kind of pressure to perform Iki is the tale of the famous courtesan Takigawa whose proprietor once had a lavish gift intended for her rival Hanaogi delivered to her quarters. After Takigawa had seen the gift and understood how loved Hanaogi the present was then taken to its correct owner. The hope was that this would push Takigawa to make herself more charming. Matsunosuke, Edo Culture, 61

[19] Mostow, “Utagawa Shunga “, 386.

[20] Mostow, “The Gender of Wakashu” 65.

[21] Gary P. Leupp. Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995,) 61-62.