Setting the Takarazuka Stage

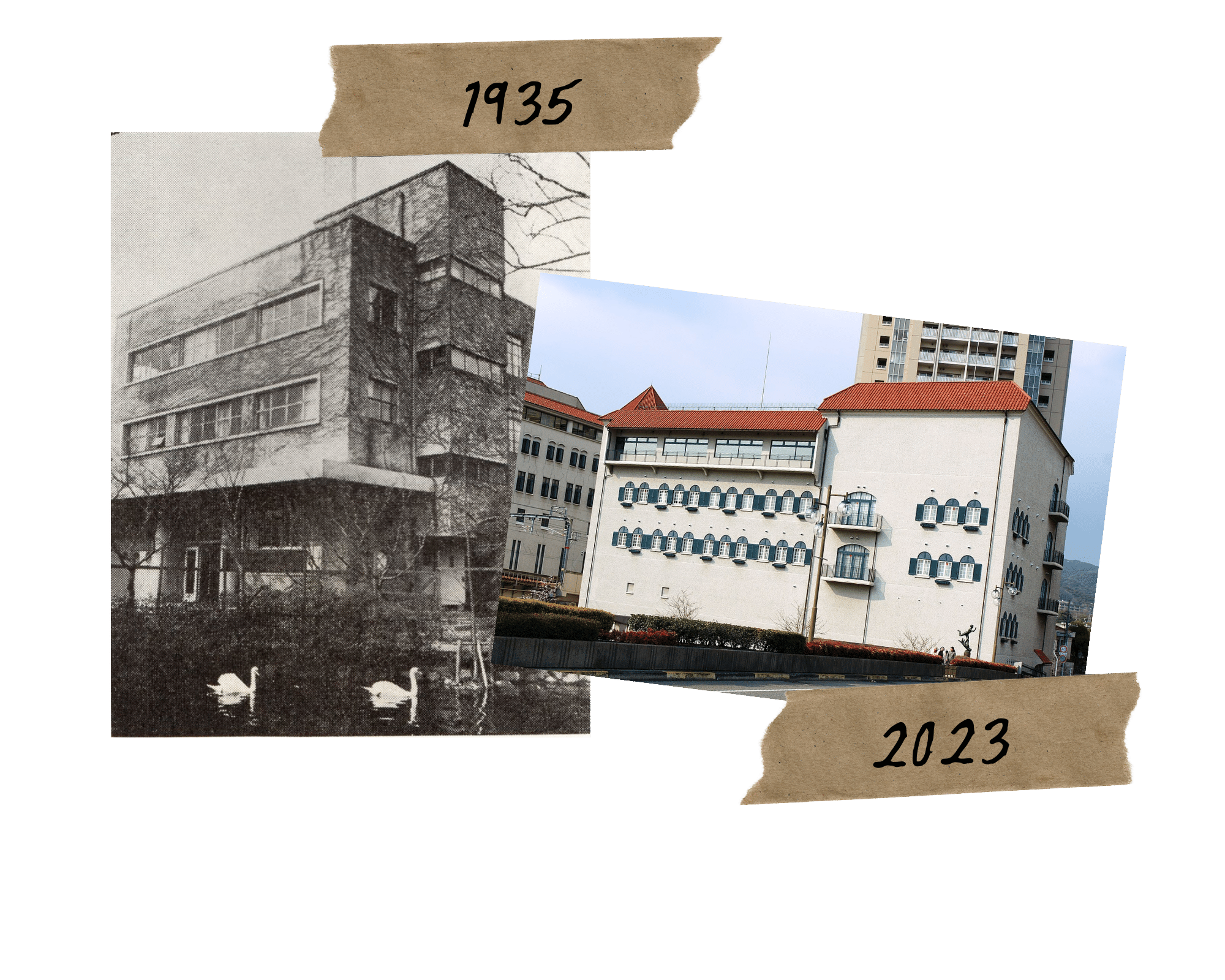

Takarazuka Grand Theater , Hyogo Prefecture

Tokyo Grand Theater, Tokyo city

Takarazuka Music School, Hyogo Prefecture

The Beginning of the Takarazuka Revue

The Takarazuka Kagekidan, or Takarazuka Revue, is an all-female theater founded in 1913. The theater produces touring musicals and revue-style performances where women play all the roles. Those specializing in male roles are called otokoyaku, and those performing the female functions are musumeyaku.[1] Kobayashi Ichizo, the managing director of the Hankyu railway company, initially conceived the revue. Hankyu grew into a larger enterprise that would include department stores and resorts. Takarazuka was the final stop on the Hankyu train line, and Kobayashi proposed making the town a tourist destination to incentivize passengers to ride the line to its end. To do this, they opened the Takarazuka Shin-onsen, the first artificial bathhouse.[2] Eventually, the pool became too burdensome, and Kobayashi needed a new attraction at the resort to replace it. His solution was the Takarazuka Revue. Following the introduction of western opera to Japan and new adaptations of traditional Japanese theater using Western music styles, Kobayashi was inspired to use the model of western theater to design his own. The theater’s original name was Takarazuka Girl’s Opera Company, and Kobayashi often argued for it to be understood as an answer to New Kabuki.[3] Kobayashi was attempting to compete with Kabuki for the attention and consideration of the Japanese public. In Kobayashi’s view, Kabuki had once been the theater of the people, but its highly formal iterations that became popular in the Meiji and Taisho periods were no longer connected to broad audiences.[4] Kobayashi always intended for the theater and productions to be all female. Although there was a short period where a male chorus was introduced alongside female performers, it was dropped completely before 1920.

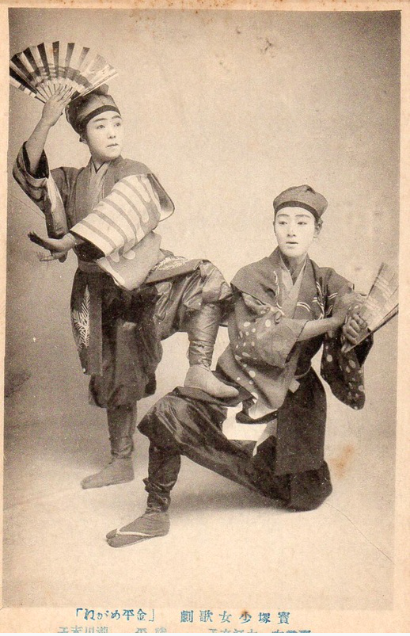

Most early Takarazuka productions took from Japanese mythology and folk tales, likely because they were the stories familiar to audiences already accustomed to Kabuki and Noh, two traditional Japanese performance art forms. Figure 13 is a promotional photograph featuring two female actors in a production of Kinpira Glasses (Figure 13), which vividly exemplifies Takarazuka’s early affinity for Nihonmono (Japanese things.) The two young women strike an archetypical pose for traditional Japanese dance and performance. The hard angles created with their bodies and prescribed hand gestures evoke Kabuki. Besides the obvious traditional subject matter of the photograph, it is also notable how bare the set is behind the girls and how difficult it is to make out the performers’ features. Most early Takarazuka photography consists of straight, full-body shots of the actresses on stark sets. Few photographs feature close-ups or the kind of glamour photography we typically associate with Western movie and theatrical stars of the early twentieth century.

Figure 14. Comparison of Kusakabe Kimbei, Dancing Girl, 1890 (left) & Photo of Takigawa Sueko and Ooe Fuiko, 1920 (right.)

This style of photography is reminiscent of early Japanese souvenir photography from the end of the previous century. Comparing the Takarazuka photo with Kusakabe Kimbei’s photograph of a cross-dressed geisha (Figure 14), several characteristics become apparent. First, despite the empty set of the Takarazuka image, it appears more dynamic than Kimbei’s since the models take kinetic poses to emphasize their roles as performers. Indeed, while the posing in Takarazuka photos from these early years is stiff and archetypal, they communicate some sense of character and story. The women were not just cross-dressing through their clothing, but they adopted mannerisms that reflected the gender of their characters. These poses also could communicate something about the story or personality of the characters, but since there is no surviving synopsis of Kinpira Glasses, we cannot be sure.

The second apparent difference in the photos is the kinds of men’s clothing the women wear in the photographs. The geisha is in Tekomai, a colorful mixture of men’s hakama, women’s kimono, and patterns with varying gendered associations. The Takarazuka actresses are in more straightforwardly masculine clothing. Their tattsuke hakama pants are paired with men’s kimono on the top, and to hide their hair, they have bandanas which would have been a common accessory for working-class men. While the designs on their fans are challenging to see, they appear to be abstract or landscape designs that would have been much more typical for men than the bright peony on the geisha’s fan. As discussed in the previous chapter, tekomai became the predominant representation of female crossdressing in the late Edo and early Meiji due to government legislation that limited the type of imagery the print industry and subsequently, the photo industry could produce. Tekomai was considered acceptable in Edo because it did not encroach on true manhood, while in the early Meiji, Kimbei and Yoshitoshi treated it as a relic of traditional Japanese culture and, therefore, not a reflection of proper modern womanhood. The Takarazuka performers are not in tekomai making their gender transformation before the camera lens more complete and relatively free of the associations attached to the tekomai costume. But, as will be elaborated below, Kobayashi Ichizo, and by extension Takarazuka, would strategically frame their employment of androgyny and performance in their visual culture to cater to whoever was listening. For their audience, Kobayashi offered something novel and subversive. For the government, he marketed it as harmless, wholesome entertainment.

Following its first ticketed performance in 1914, the theater experienced a steady development and, eventually a rapid expansion. Takarazuka’s success was in no small part to the economic and political fertile ground of the Taisho period. World War I left Japan with inflation and an energized pro-democratic movement that fostered robust party politics and expansion of the Japanese cultural identity.[5] Kobayashi was known for his artistic sensibilities, but he was better known for his economic savviness, and he took full advantage of the economic situation to grow Takarazuka into a national brand. This background for Takarazuka is significant because it frames the theater as a commercial enterprise rather than an artistic or ideological one, which helps explain how the theater negotiated ideology with commercial appeal. In the realm of ideology, the theater feature that played an important role was the Takarazuka Music and Opera School (Takarazuka ongaku kageki gakko) opened in 1919. This private vocational school, still running today, trained recruits for the theater during its early years. It also taught practical subjects following the government-set curriculum. Since the school also enforced strict rules of behavior and etiquette, it was like the girl’s finishing schools founded during the Meiji period.[6]

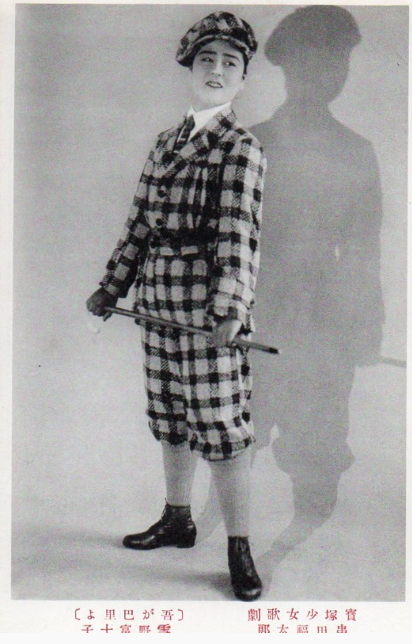

Figure 15. Yukino Fujiko in “Mon Paris”, 1927. Sumire Collection (Online Archive).

Through the 1920s, the Revue changed locations and administrative formations. The most glaring difference from the Takarazuka theater today is that the girls would switch between male or female roles, presumably based on one’s ability to play the part.[7] This fluidity in gender performance was like Kabuki before the nineteenth century, which commonly used male and female actors during their careers. Despite the lack of role codification, early Takarazuka still featured images of convincing gender play because of the reliance on Nihonmono. Japanese traditional clothing, while gendered, also allowed for more ease in convincingly playing the opposite sex. As pointed out by Takeda Sachiko, “For cross-dressing to work, clothing must cover the body loosely and entirely so that male and female physical, sexual difference is displayed as little as possible on the body surface…”[8] The voluminous layers, boxy silhouettes, and covered skin of traditional Japanese ensembles allowed for laxity in other aspects of the gender performance. Long hair could be hidden or read as appropriate for the period being depicted. The matching white stage makeup worn by both male role and female role performers was a standard brought from traditional Japanese theater, so if the sexual difference of their bodies was hidden, their crossover of the gender boundary could be a successful one.

But eventually, like all commercial ventures, Takarazuka had to follow the market trends and started to put on more western-style productions to cater to increasingly Westernized tastes. The performance that marked the significant change in the theater was Mon Paris. Written by an in-house composer of the Takarazuka after a trip to Paris, where he attended a cabaret, Mon Paris not only introduced cabaret aesthetics to the theatrical language of Takarazuka but also led to a shift in prioritizing Western style productions over Japanese ones. Western clothing now comprised the bulk of the costumes, which meant the theater had to tackle a whole new sartorial system, losing the protection that traditional Japanese clothing afforded them. The form-fitted tailoring of Western suits meant that the physical difference in the actresses’ bodies were more readily apparent. Thus, the theater had to compensate in other areas of the performance and aesthetics so that the illusion of the male role performers wasn’t broken.

A photo of Yukino Fujiko for the 1927 production of Mon Paris (Figure 15) pictures the shift to favoring contemporary Western clothing styles and more stylized makeup paired and more dramatic lighting and ambiance while continuing some earlier tactics of presenting androgyny. Yukino is dressed in a bold checkered pattern matching suit with dark gloves, hat, and cane. Her stance is wide and bold, foreshadowing the signature physicality of the otokoyaku that would develop in the following decade: straight lines and hard angles. Her hair is hidden under a hat, which was a common practice since actresses were not yet allowed to cut their hair short. Retaining her long hair and the careful painting of her features to accentuate her eyes and lips were strategies for maintaining a sense of androgyny in the absence of traditional Japanese clothing that could hide her body. The photo is still shot on a stark set, but some personality is added with her shadow on the backdrop, dramatizing the shot and making her look larger. These elements reveal a more sophisticated visual language the theater employs and foreshadows the unique and complex photographic style the theater adopted in the 1930s to turn their actresses into starlets.

[1] Onnayaku is sometimes used interchangeably with musumeyaku but onnayaku typically refers to older female role players and not the actresses who play the romantic leads in the shows.

[2] Makiko Yamanashi, A History of the Takarazuka Revue Since 1914: Modernity, Girls’ Culture, Japan Pop (Boston: Leiden Global Oriental, 2012), 6.

[3] Yamanashi, A History of the Takarazuka, 10.

[4] Yamanashi, A History of the Takarazuka, 10.

[5] Yamanashi, A History of the Takarazuka, 17.

[6] Kobayashi Ichizo had created a motto for the theater and academy: Kiyoku, tadashiku, utsukushiku (to cultivate purity, integrity, and grace.) This meant the girls needed to live up to a standard of politeness and purity to protect their reputation and the reputation of the theater.

[7] Male and female roles were not codified positions in Takarazuka prior to the 1930s. This meant that there was no specific training to play and male role or female role in the school. This would change when the roles were codified but at this point the girls were presumably educated the same way. Yamanashi, A History of the Takarazuka, 38.

[8] Takeda, “Menswear, Womenswear,” 205.