How to compose a summary analysis:

For the first two analyses, you should take one section of a text we’ve read this semester: Fleming’s City of Rhetoric, Schindler’s, “Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination and Segregation Through Physical Design of the Built Environment,” or Rice’s “Inquiry as Social Action.” In other words, you might choose “Part I” in Schindler or “Part 2” in Fleming.

Project Purpose and Goals: This exercise gives you practice analyzing complex academic essays. Accomplishing this task requires several moves. First, we must comprehend the text we are analyzing in order to locate its main argument, which will become our claim. Then we must support this claim with textual evidence. And, finally, put the claim in context by explaining the broader conversion in which the text arises. A reading analysis differs from a “plot summary” because we do not chronologically repeat the author’s text in our words; rather, we distill what we think the text’s main argument is for our own purposes.

This analysis should mostly be in your own words, but you might want to quote a few key words and phrases that you think particularly articulate the author’s main argument.

You may want read the text or particular sections of the text multiple times before beginning your analysis. I encourage you to first compose your analysis in your own words without looking at the text before returning to it to add some key words and phrases to bolster your claims or help your audience better understand your claim.

In your conclusion, you should discuss the “so what?” Why does this argument matter? How might it be useful to someone doing the kind of research you are doing in this class? What’s at stake?

In short, a reading analysis creates what Graff and Birkenstein call a “They Say.”

This project is designed as an opportunity to practice gathering, summarizing, synthesizing, and explaining information from various sources.

Instructional Readings for writing summaries:

See Graff, Ch 1-3.

Guidelines

*Use the literary present tense, i. e. “Thomas Jefferson argues . . .”

*Cite paraphrased details and quotations (see EasyWriter for in-text citation)

*Limit quotations (1-3, brief, and only if the original language is very important)

*Include the bibliographic information (see EasyWriter MLA guide for end citation)

*Consider multi-modes when composing in the blog post: spatial, visual, linguistic

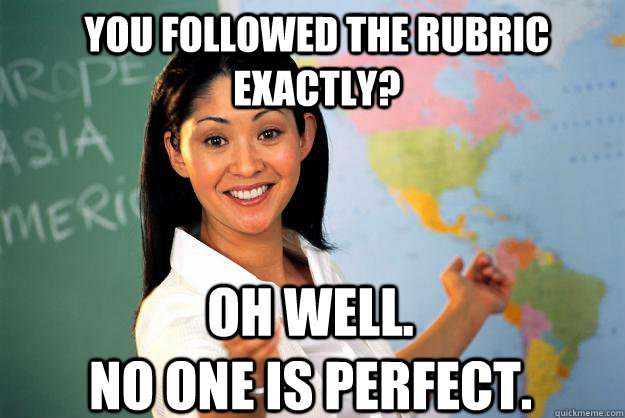

Click here to see a copy of the evaluation rubric.

On Form:

While your reading analyses’ content certainly matters, you should also pay particular attention their form. Since you are composing using academic conventions, you should use one of the three openings Graff describes in TS/IS. You should also focus on “connecting the parts” (107), on using “signal verbs that fit the action (38), on “framing every quotation” (44), by using signal phrases (46) and commenting on the quote (47) to reveal the connection between claim and evidence.

Category: “readings” and “wrtg100f16”

Tags: “Author” and “readings” and others of your choosing. Think about why we use tags and why they are helpful and tag accordingly.