Introduction

Histories of Impressionism typically begin in 1874, with the group’s first exhibition independent of the annual Paris Salon. Arguably, though, Impressionism originated in 1867, three years prior to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. In May of that year, painter Frédéric Bazille (Figure 1) wrote to his parents explaining the ambitions of himself and a group of his peers to create an alternative to the Salon. However, disappointed, he wrote, “with each of us pledging as much as possible, we have been able to gather the sum of 2,500 francs, which is not enough. We will have to re-enter the bosom of the administration whose milk we have not sucked and who disowns us.”[1] Two years later, outraged after having only one painting accepted at the Salon, Bazille wrote to his parents again, stating, “I will never send anything again to the jury.”[2] He, along with his colleagues, had decided “that each year we will exhibit our works in as large a number as we wish. We will invite any painters who wish to send us work. [Gustave]Courbet, [Jean-Baptiste-Camille] Corot, [Narcisse Virgilio] Díaz, [Charles-Fraçois] Daubigny, and many others… have promised to send work and heartily support our idea. With these people, and Monet, the best of all of them, we are certain of success. You will see how much attention we will get.”[3] But Bazille would not live to see this venture come to fruition. In July 1870, war was declared; in August, the young painter joined a Zouave unit and went into battle; on November 28, the artist was killed in the Battle of Beaune-la-Rotonde.[4]

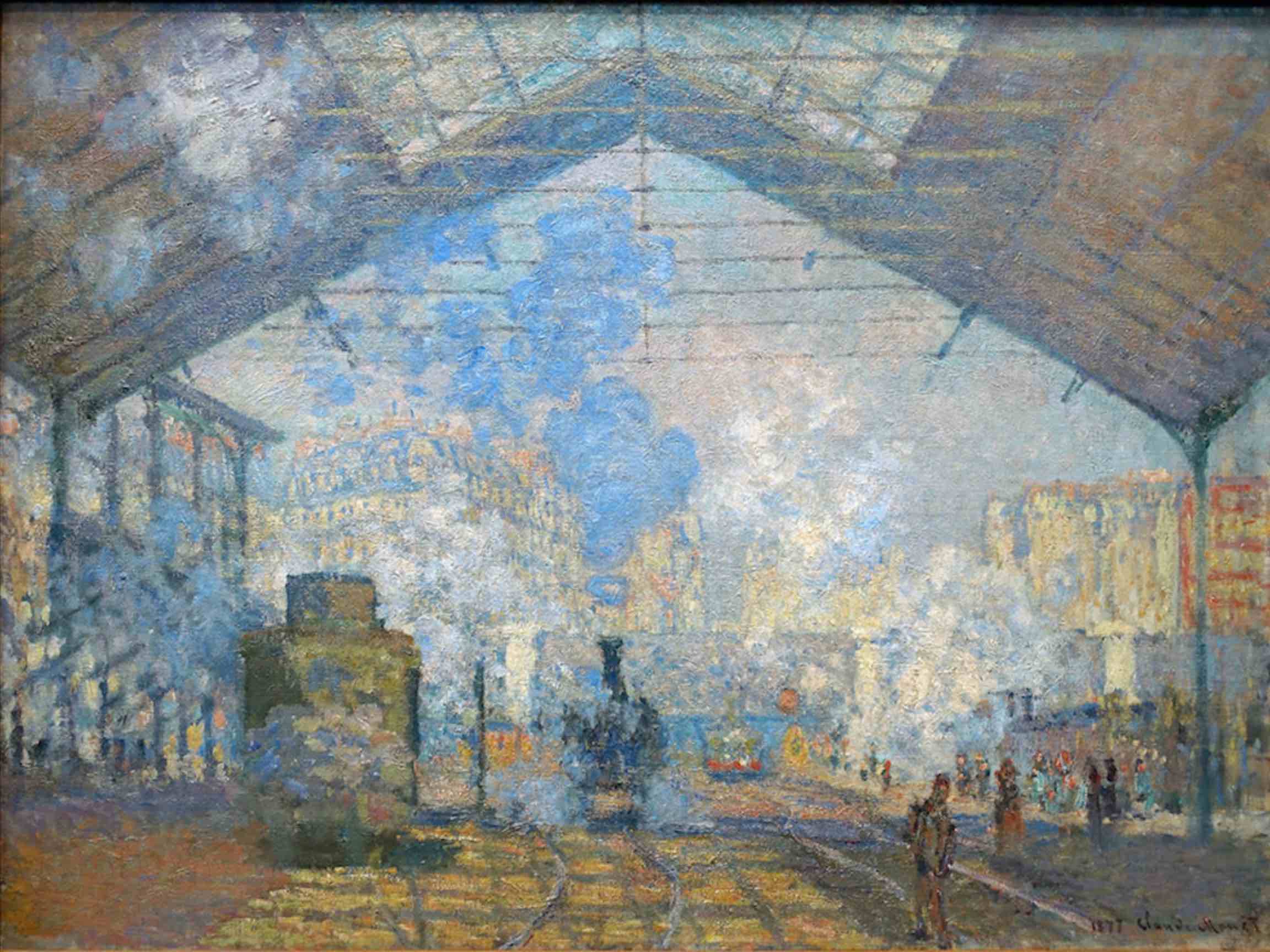

By the time the exhibition that Bazille had helped to plan opened in 1874, the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune had inalterably changed France and especially the city of Paris. After the Prussians laid siege to the city in the course of their resounding military victory against the French, a civil war known as the Paris Commune wrought further destruction. These two wars left landmarks, bridges, railroad stations (Figure 2), homes, and parks in and around Paris in ruins; many of these sites remained unrepaired for years. This capstone demonstrates that these were the very locations that the Impressionists chose to depict in the immediate aftermath of these events. To visualize this significant overlap, this project employs a digital mapping platform connecting 45 Impressionist paintings of the 1870s with 18 locations in and around Paris that were impacted by the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune. Collectively, these paintings show that the conflicts of 1870-71 continued to resonate long after the fighting was over.

Until recently, the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune have not figured prominently in accounts of Impressionism. This is especially surprising given that a socio-historical approach has been dominant in scholarship on the movement since the 1980s, with the publication of T.J. Clark’s Painting of Modern Life and Robert Herbert’s Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society.[5] Clark and Herbert both focus on the Impressionists’ depiction of the “New Paris” that corresponded with the rise of the bourgeoisie in the 1860s and 70s. Clark in particular draws a link between the lack of clarity in Manet’s paintings of modern life in Paris and the mixing of social classes that became increasingly common in this period. He and Herbert both associate Impressionism with the emerging society of spectacle enabled by “Haussmannization,” the ambitious project of urban renewal carried out by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Prefect of the Seine under Napoleon III. Haussmann’s construction of wide sweeping boulevards and parks produced new forms of leisure, commerce, and entertainment. Importantly, neither Herbert nor Clark make substantive distinctions between the political culture of the Second Empire and the Third Republic, and give little weight to the destructive events of 1870-71.

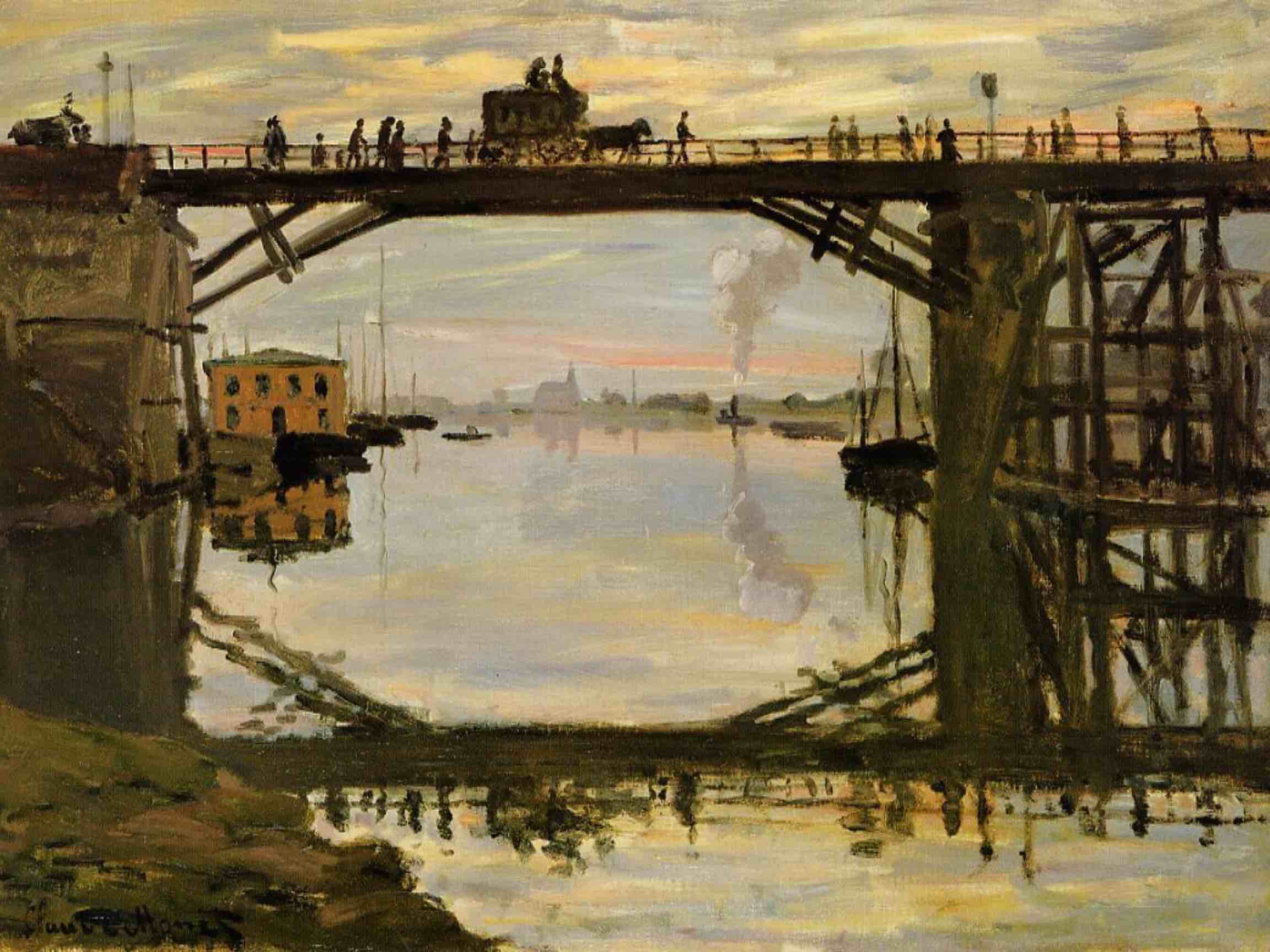

Figure 3: Claude Monet, The Highway Bridge Under Repair, 1872. Oil on canvas, 54 cm x 73 cm. Foundation Rau pour le Tiers-Monde.

Figure 4: Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 48 × 63 cm. Musée Marmotan, Paris, France.

Figure 5: Edgar Degas, Place de la Concorde, 1875. Oil on canvas, 78.4 × 117.5 cm. Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

In a series of publications in the 1980s and 90s, Paul Hayes Tucker and Albert Boime began to relate Impressionist paintings to the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune. Tucker’s publications center on Monet, especially on the paintings he made in Argenteuil during the 1870s.[6] As Tucker highlights, Argenteuil suffered major damage during the Franco-Prussian War, as its two most important modes of transportation, the railroad bridge and the pedestrian bridge (Figure 3), were both destroyed by the Prussians in the final siege. Tucker construes Monet’s decision to repeatedly paint these rebuilt bridges as a gesture laden with patriotism.[7] Similarly, in his analysis of Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872; Figure 4), a painting that depicts the bustling port of Le Havre, Tucker argues that the artist represented “a new day dawning for a revivified France,” with its physical fabric and its economy back to normal after paying punishing reparations to Prussia.[8] Similarly, Albert Boime’s book Art and the French Commune: Imagining Paris After War and Revolution examines the rise of Impressionism in relation to the efforts of the Third Republic to “rebuild” Paris and erase all reminders of the war and the Commune. Boime argues that the Impressionists’ focus on spaces of leisure and entertainment constitute an effort to reclaim Paris’s rebirth and renewal following the mass destruction of 1870-71.[9]

Building upon the work of Tucker and Boime, André Dombrowski and Hollis Clayson investigated further connections between Impressionism and the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune. Dombrowski’s analysis of Edgar Degas’s painting, Place de la Concorde (1875; Figure 5) highlights the way in which the artist uses geographical location and meticulous pictorial maneuvers to make the memories of 1870-71 and the politics of the Third Republic visible, rather than suppressed.[10] After the French lost the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to the Prussians, James Pradier’s sculpture, The City of Strasbourg, located in the Place de la Concorde, served as a symbol of the crushing defeat. In his analysis, Dombrowski notes how Degas utilizes the black top hat of Viscount Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic –the artist, friend, and Bonapartist sympathizer whom the artist chose as the model for the smoking man on the right—to cover the sculpture of the City of Strasbourg.[11] He argues that the concealment of the sculpture should not be understood as a means of forgetting or erasing the recent history, but rather as a means of highlighting the repercussions of 1870-71 that France had to face during the then current state of the Third Republic.[12] Clayson’s book Paris in Despair: Art and Everyday Life under Siege (1870-71), primarily examines six artists and their works –including Impressionists Manet, Degas, and Caillebotte—in relation to the harsh effects of the Siege of Paris. Clayson explores the psychological and social impacts inflicted on the artists and their artistic practices while working and living in destruction. This artist-centered book recounts the experiences of these catastrophic events and builds an understanding on how the war and Commune impacted the visual culture produced during this time.

In spite of the important work that these scholars have done to unveil the connections between Impressionism and the events of 1870-71, more work remains to do justice to the scope of those connections. By mapping out these connections, this capstone uses both visual and textual, quantitative and qualitative evidence to demonstrate how intertwined this movement was with these events. Maps thus give us a tool to analyze these works in relation to one another, rather than in relative isolation.

[1] Bazille to his parents [May] 1867, as cited in G. Poulain, Bazille et ses amis (Paris, 1932), 208 and trans. J. Patrice Marandel, Bazille and Early Impressionism, exh. Cat. (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1978), 180.

[2] Bazille to his parents [May] 1869, as cited in Poulain, 207-208, and trans. Marandel, 180.

[3] Bazille to his parents [May] 1869, as cited in Poulain, 207-208, and trans. Marandel, 180.

[4] Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby has argued, through the works of Gros, Girodet, and Delacroix that turcos, mamelukes, and Zouaves formed crucial public components of the Napoleonic wars and subsequent foreign interventions. See Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); The Zouaves were originally composed of only native Africans. Frenchmen believed that being a Zouave afforded more freedom and more glory than their traditional regiments. See Mary Manning, “Frédéric Bazille and Masculinity between Paris and Montpellier, 1841-1870” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Rutgers University, 2015), 264.

[5] Herbert, Robert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society. New Haven: Yale University Press, 19888; T.J. Clark The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, Revised ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999).

[6] For more of Tucker’s work on Monet and Argenteuil see Paul Hayes Tucker, Monet at Argenteuil (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982); Paul Hayes Tucker, “Monet at Argenteuil: 1871-1878,” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Yale University, 1979); Paul Hayes Tucker, Claude Monet: Life and Art, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995); Paul Hayes Tucker, The Impressionists at Argenteuil, (Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2000).

[7]Paul Hayes Tucker, The Impressionists at Argenteuil, (Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2000).

[8] Paul Hayes Tucker, The Impressionists at Argenteuil, (Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2000).

[9] Albert Boime, Art and the French Commune: Imagining Paris after War and Revolution, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

[10] André Dombrowski, “History, Memory, and Instantaneity in Edgar Degas’s Place de la Concorde” The Art Bulletin, 93, no. 2 (June 2011): 195.

[11] André Dombrowski, “History, Memory, and Instantaneity in Edgar Degas’s Place de la Concorde” The Art Bulletin, 93, no. 2 (June 2011): 195.

[12] Dombrowski, “History, Memory, and Instantaneity in Edgar Degas’s Place de la Concorde,” 195.