Northern China and the Korean Peninsula

The contact between the Korean Peninsula and China goes back for more than a millennium. China provided the model for literature, art, and political structure, as well as popular religions and philosophies, especially Confucianism and Buddhism. The last dynasty in Korea, the Joseon dynasty (1392 CE-1897 CE), had been a loyal vassal state to the Ming (1368 CE-1644 CE) and later Qing dynasty (1644 CE-1912 CE) for more than five hundred years. The long history of their relationship and the close geographic location of the two nations encouraged frequent cultural exchange between Korea and China, both official and civil. The official diplomatic contacts, as well as merchants, scholars, and immigrants travelled in both directions and brought together different ideas and traditions, which later merged into a shared culture that exists across the political border.

The movement of objects is the most visible evidence of the cultural exchange, and the foreign objects in Korean still-life panting, Chaekgeori, reflect the cultural connection between China and Korea.

Chaekgeori, which means “books and things,” is a still-life painting genre that emerged in Joseon Kore during the late 18th century. Chaekgeori depicts a verity of objects like books, porcelain, scrolls, and flowers, which reflects that taste of the middle and literati class and often contains auspicious meanings.

Painting of Scholar’s Equipment. Ink and color on silk, 198.8×39.3 cm (Each panel). Joseon Dynasty, Korea. National Museum of Korea.

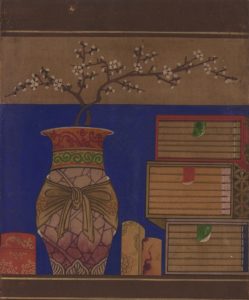

Objects from China or based on Chinese designs can often be seen in a Chaekgeori painting. In Painting of Scholar’s Equipment, a Chaekgeori folding screen from Joseon dynasty, many of the objects displayed on the bookshelf shows clear Chinese origin or shared aesthetics.

- Painting of Scholar’s Equipment (Partial)

- Jar with Floral Scrolls and Wrapped-Cloth Design. Painted enamel on copper, 25.4×19.1×9.5 cm. Qing Dynasty, China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There are many porcelain vases depicted in the painting, and a number of the vases have fabric tied around them as decoration. This practice was common in both Joseon Korea and Qing dynasty China. Chines artisans even incorporated the fabric decoration into the surface design of enamel painted vase.[1]

- Painting of Scholar’s Equipment (Partial))

- Three-Legged Vessel of Archaistic Design. Bronze, 21×13.3×13.3 cm. Qing Dynasty, China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The tripod vessel in the painting represents the bronze vessel from China, which is likely to be a Qing dynasty imitation of ancient bronze vessel, as archaistic bronze vessels was very popular among the Chinese elites during the time.

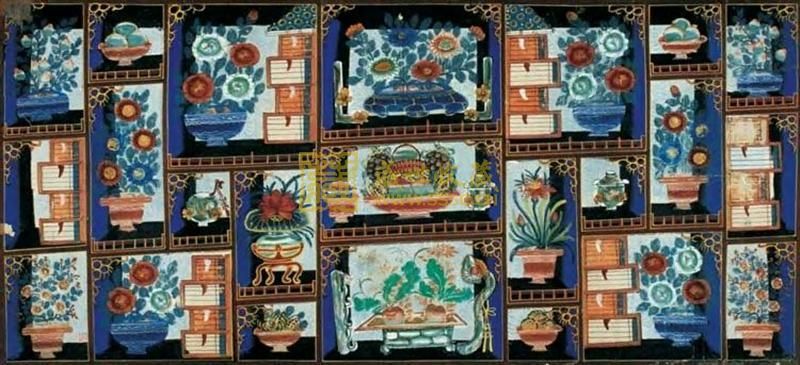

Furthermore, the composition of the bookshelf-style Chaekgeori is also influenced by the Chinese display culture during Qing dynasty, especially the Duobaoge, a cabinet for displaying collectibles of different shapes and sizes. The Duobaoge cabinet also inspired a painting genre of the same name, Duobaoge Jing (多宝格景, A View of Duobaoge Cabinet), which can often be found as the interior décor of imperial palaces. Later, the Duobaoge Jing painting spread to the civilian class.[2]

The Duobaoge Jing print above is New Year Picture made during the mid-Qing dynasty. Since this kind of woodblock prints were usually targeted at the middle-class costumers, instead of porcelain and bronze vessels, there are more auspicious flowers and fruits on the shelf. Although the shapes of the bookshelves are not exactly the same, the composition of the Duobaoge Jing is very similar to the Chaekgeori painting from Korea, which shows that not only did objects move across border between to two countries, but culture and lifestyle trend as well.

[1] Eleanor Soo-ah Hyun. “Korean Chaekgeori Paintings.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chae/hd_chae.htm (December 2016).

[2] Sunyoung Jun. “The Spreading and Evolution of Traditional Chinese Auspicious Paintings into Korea.” East China Normal University. Dissertation. 2013: 312.