Evolution through Time

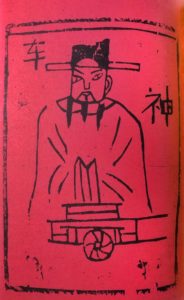

Vehicle God

Through their long evolution, most images of major gods of nature and gods of mainstream religions (Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism) have eventually been standardized in form and passed along generations, with only minor variations made by individual makers, but because of their close connection to people’s life, many gods of daily life continued to evolve with the changing lifestyle. Ironically, since the early 20th century, when life in China began to modernize dramatically, cultural elites condemned all the old folk beliefs as obstacles in their path toward a modern China. With the government’s discouragement towards folk practices, the presence of paper gods largely faded away by the mid-century.[1] Nonetheless, the use of paper gods survived in some rural areas, and the artisans of paper gods in the modern era, following what their forebears had practiced, created prints that reflect villagers’ changing needs.

Among these “modernized” paper gods, the most notable example is the Vehicle God from Neiqiu. The Vehicle God depicts the common vehicles of transportation. The locals usually paste the prints of Vehicle God in their courtyards and, as the name suggests, on their vehicles during major festivals. They make offerings to the Vehicle God during the Spring Festival and before leaving for a long trip or the temple fairs and praying for a safe travel. If an accident happened within the year, the family would stop worshipping the god in the next year as a punishment for failing to protect them.

As a paper god directly responsible for protecting the vehicles, the images of the Vehicle God changed with the type and appearance of the vehicles commonly used by the locals in Neiqiu.

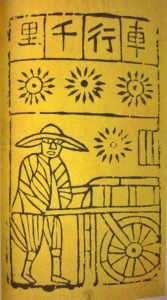

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 17×8 cm. Qing Dyansty. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

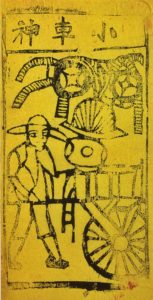

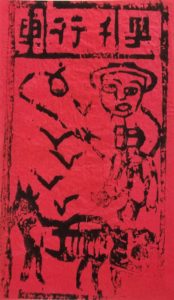

- Vehicle God. Woodblokc Print, 16.5×8.5 cm. Republic Period. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

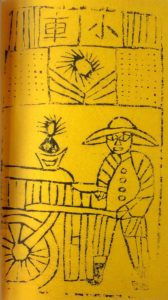

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 16.8×8.8 cm. Republic Period. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

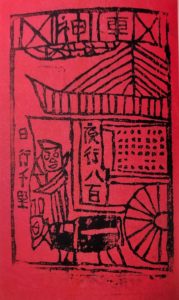

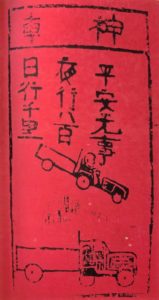

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 15.8×8.5 cm. Republic Period. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

The images from the Qing dynasty shows a man wearing a straw-hat pushing a wheelbarrow with the sun motifs above him. A similar design can be found on the prints from the Republic era, with motifs of coins and gold ingots, both symbolizing wealth. In addition, a man driving a carriage is also a common image of the Vehicle God during this time, since both carriage and wheelbarrow were the most common vehicles for transporting people and goods.

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 16.8×8.2 cm. Republic Period. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 15.8×8 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

After automobiles were introduced in China, new images appeared on the Vehicle God prints. In a print from the Republic era, the image of a truck is placed underneath a wheelbarrow, with the inscription “travel a thousand miles at day; travel eight hundred miles at night; (travel) safely with no accident.” Although it was unlikely for any local villagers then to own a truck, its appearance on paper gods indicates that the locals had identified automobiles as a major method of transportation.

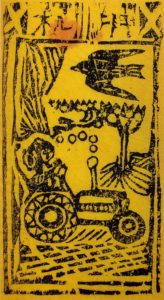

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, as the country further industrialized, the images of automobiles on Vehicle God prints became more common and diverse. A print from this period has the same inscription and similar composition as the one form the Republican era. However, in the place of the wheelbarrow, the maker put a tractor instead, since it had become a common transportation method and farming device in rural China.

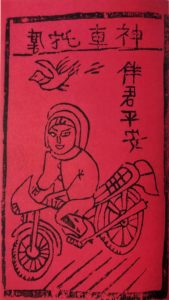

- Motorcycle God. Woodblock Print, 16×9 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

- Motorcycle God. Woodblock Print, 15.8×7.8 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

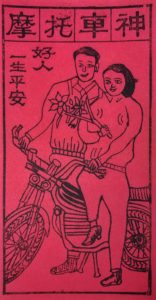

- Tricycle God. Woodblock Print, 15.5×8.5 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

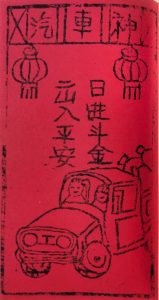

- Car God. Woodblock Print, 15.5×8.3 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

Furthermore, as the people of Neiqiu were introduced to a variety of vehicles, they were no longer satisfied with one broad Vehicle God. New prints dedicated to individual type of vehicles were created, such as the Car God, the Motorcycle God, and the Tricycle God. The figures included in these prints also reflect the changing fashion in the region: they are no longer wearing straw hats and buttoned shirts, but wearing pullovers, jackets, and helmets. An image of the Motorcycle God also includes a woman in high heels, holding a bouquet of flowers in one hand, and holding the handlebar in the other hand. She is possibly the wife of the man behind her, who is also dressed in a shirt and a vest fashionable at the time. This shows that the rural area was also influenced by the imported modern culture. The depiction of the couple not only shows that the people of the area began to seek up-to-date fashion and lifestyle, they also began to interpret marriage as a romantic act between man and woman instead of fulfilling a social or familial obligation. This shows a shift both in the material culture and people’s perceptions on society.

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 13.8×9.5 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 16×9 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 14.5×10.5 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

- Vehicle God. Woodblock Print, 15×8.5 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

Even with so many social changes and innovations, the people of Neiqiu never abandoned their old images. The images of the wheelbarrow and carriage were still produced, not as a representation of their daily life, but as the symbol of the deity. Some printmakers chose to combine the old and the new, creating images in traditional forms but with a touch of modernity. For example, the image on the lower left is divided into two sections. A male figure dressing as government official from imperial China is depicted in the upper section, and the cloud motifs around him indicates his identity as a divine being, a representation of the Vehicle God. In contrast with the traditional image of the deity, the section below shows a detailed image of a modern tractor. Similarly, the image on the lower right shows an overall traditional image with a man in traditional peasant clothing, a straw hat and a buttoned shirt, driving a horse carriage. However, the wheel of the carriage at the lower right corner clearly bears the thread pattern of rubber tire, which has replaced the old wooden tire in modern Chinese countryside. These hybrid images are the continuation of the traditional representations that passed down through generations with up-to-date images of modern vehicles used in local daily life.

Machine God

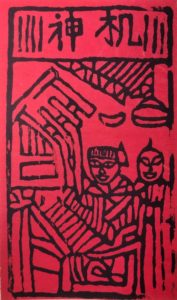

- Machine God. Woodblock Print, 15.3×8.5 cm. Republic Peroid. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Private Collection.

- Machine God. Woodblock Print, 21.5×10 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

Another notable switch of subjects through time is the Machine God. Before China’s modernization, the image of Machine God (Ji Shen, 机神) is a woman working on a loom, as the machine (ji, 机) refers to the loom (zhibu ji, 织布机), one of the primary tool of production in a household. However, after the Opium War in 1840, China was forced into trading with the Western countries. Large amounts of mass-produced textiles imported from the West began to infiltrate the Chinese market and replaced the traditional hand-woven textiles made by family workshops.[3] As Chinese industrialists began to build modern textile factories, the traditional loom lost its place in people’s daily works. Instead, tractors (tuola ji, 拖拉机), the modern machine used in farming, became the new primary instrument of production. As a result, the modern machine replaced the old one and became the new image of the Machine God.

[1] Geng, Han. Folk Apotheosis in China: Neiqiu Shenma and Folk Religion Practices. Guangxi Normal University Press. 2016: 24.

[2] Geng, Han. Folk Apotheosis in China: Neiqiu Shenma and Folk Religion Practices: 290.

[3] Zhu Li-xia and Huang Jiang-hua. “The Historical Position of Modern Chinese Textile Industry.” Journal of Wuhan Textile University, Vol. 26, No. 4 (2013): 13.