Hair: Female Signifier of Sin

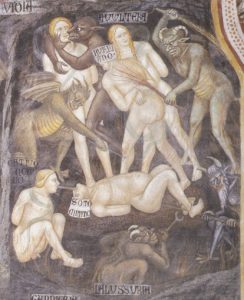

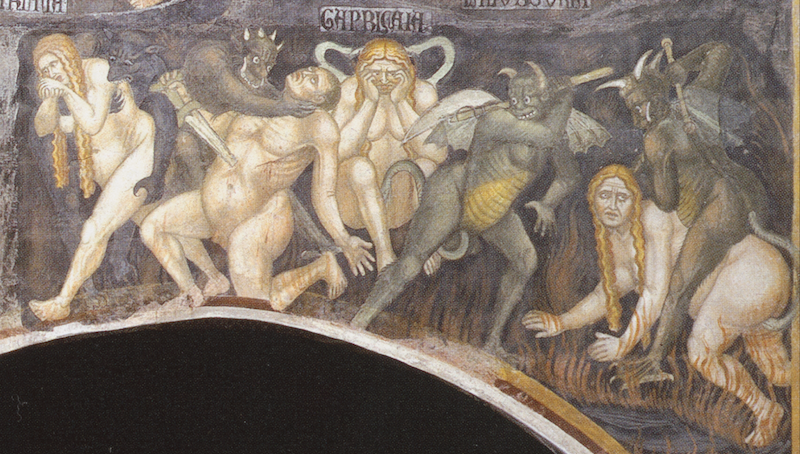

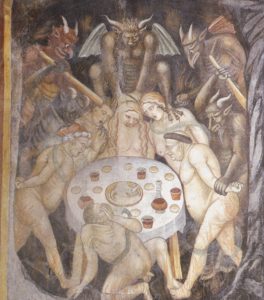

These implicit misogynistic societal views are visible within the imagery of Taddeo di Bartolo’s Hell fresco at the Collegiata church of San Gimignano. Although there is a greater number of men punished, when women are depicted on the fresco, they are overwhelmingly punished sexually or with sexualized methods of torture. These women are groped, prodded, and mounted by demons. One distinguishing feature these women share is long, loose reddish-blonde hair. Multiple women are shown with loose tangled hair that is grabbed by demons and twisted around demonic tails [figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, & 10].

In the Middle Ages women were caught between conflicting messages regarding their appearance. Long, uncovered hair was acceptable for young women, as long as they were not too concerned with ornamentation. When married, by contrast, veiling and pinned up hair was the norm. (1) Women covering their hair once married was yet another way men regulated the bodies of women. “Wilder” and closer to nature when young and unmarried, women were “civilized” and controlled by their husbands when married. They were raised with the understanding that their appearance was the primary defining quality that would tell society they were good and beautiful and thus worthy of marriage. (2) However, too much attention paid to appearance would draw accusations of vanity. Roberta Milliken explained that “according to church fathers, women who display and style one of their most alluring feminine features, their long locks, are lust-filled…to actually see a woman engaging in this behavior would amplify the eroticism of the act and its dire consequences.” (3)

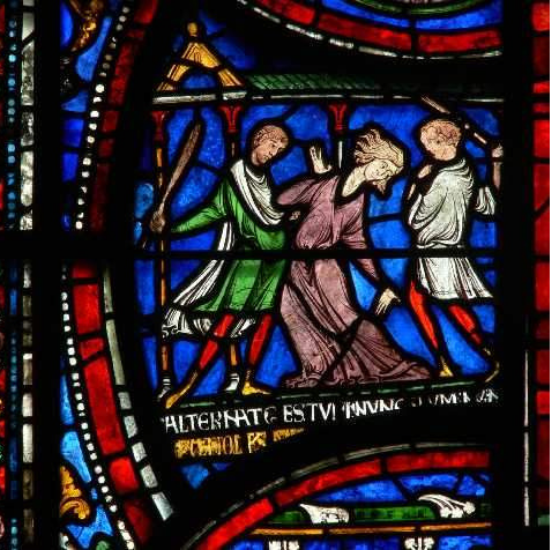

[Fig. 13] Mad Matilda (detail), Canterbury Cathedral, Trinity Chapel, stained glass, c. 13th century, Canterbury, United Kingdom.

[Fig. 14] Anonymous, Winterfeld Diptych (detail), c. 1430, National Museum in Warsaw.

Medieval images of sinful women depict this fixation of hair as a marker of female deviancy. Dating around the 13th century, one scene from the stained glass at Canterbury Cathedral depicts the figure of Mad Matilda of Cologne. In a detail located to the left of the central square, Matilda is shown in utter disarray as two men beat her with clubs [fig. 13]. Accused of infanticide, Matilda is marked as sinful in part due to the wild, unkept hair that haloes around her body, which writhes in a serpentine S curve away from the clubs.

In the early centuries of Christianity, believers identified the figures of Mary of Bethany, sister of Lazarus and Martha in John’s Gospel, and the ‘sinner’ in the Gospel of Luke named as Mary who anointed Jesus and wiped her tears off his feet with her hair, with the figure of Mary Magdalene. (4) Thus the visual persona of Mary Magdalene in the Middle Ages included many depictions of the woman with long free-flowing hair. Mary Magdalene is often present in scenes of the Crucifixion, where she is shown at the feet of Christ or visibly expressing her grief. For example, in a detail of Lorenzo and Jacopo Salimbeni’s The Crucifixion, Mary Magdalene, witnessing Jesus’s death, raises her hands up to heaven and yells in anguish [fig. 15]. She has long, curled blonde hair that hangs to her waist. It seems here that the emphasis is on Mary’s love for Jesus, as she is in the process of expressing despair during the moment of his death. (5) As such, her long hair then serves as reference to her anointing of his feet as Mary in John’s Gospel and ‘sinner’ in Luke, where she was overcome with emotion and used her hair to wipe her tears off the body of Christ.

In line with medical beliefs that the character of the body is representative of moral quality, long disheveled hair was a marker of an immoral, loose woman. (6) “Good” women were in control of their virtue (sexuality) and so they controlled their hair, which was a public signifier for her sensual capability. It can also be a signifier for women who live outside the margins of male-controlled society, such as the Wild Woman, or even the Magdalene after the Resurrection. (7) According to The Golden Legend (c. 1260), after Jesus’s resurrection, Mary travelled to France and lived alone as a contemplative hermit for thirty years. While in isolation, she grew her hair long to preserve her modesty. In the Winterfeld Diptych (c. 1430), by an anonymous artist, Mary Magdalene is shown surrounded by angels, ascending into the sky [fig. 14]. The Magdalene is clothed in tawny brown hair, covering her entire body and flowing from her head. Although her long hair is meant to protect her modesty, Martha Easton noted that images of the hermit Magdalene have very little visual difference to the iconography of the sexually promiscuous Wild Woman. (8) Mary’s status as a hermit marks her as another type of woman who lives absent from men’s control, her long hair also becoming a marker of untamed wild-ness.

Hair was such a prominent feature of Taddeo’s women because they represent and communicate cautionary tales of “bad” women. When combined with the depiction of their nude writhing bodies, the long reddish blonde hair of Taddeo’s women denotes a connection between their femininity and their sexual sinful natures.

In one of the more disturbing motifs from Taddeo’s Hell, a woman with long reddish blonde hair crouches on her hands and knees [fig. 16]. A demon kneels over her and raises an instrument in his hand to strike her as he sodomizes her with his serpentine tail. The woman is in a submissive crawling position, looking up morosely to the demon who assaults her. Her long hair hangs down in curls around her face. The tresses cover her chest, blocking the obscured view of her breasts. The bright lines of the woman’s hair, an almost glowing strawberry blonde against a very dark background, draws the viewer’s eye to her anguished face and then down to the webbed monstrous feet of the demon, surrounded by the fires of hell. From there, the eye is drawn up the demon’s body and down to the tail, where it enters the woman’s body. In another scene of torture, a female demon (the only one in the fresco) pierces a woman’s genitals [fig. 7]. The tortured woman’s gaze meets the eyes of the female with an expression that gives the appearance of perverse intimacy. As another demon pours a vat of hot fiery liquid over her head, the woman attempts to cover her chest in a display of modesty and defense that perhaps comes a little too late. A third demon winds his tail through the woman’s very long hair. Above her, to the left, another woman is shown with a demon grabbing her hair, as he uses the fingers on his other hand to pull her mouth apart in an act of domination and humiliation.

[Fig. 15] Lorenzo and Jacopo Salimbeni, The Crucifixion (detail), fresco, c. 1416, Oratorio of St. John the Baptist, Urbino, Italy.

These women are defined by their hair; it marks their femininity and the sexuality associated with that designation. The woman viewing these tortured figures would view them through the lens of their own experience. From a young age, they heard the admonitions from religious and familial leaders that controlled hair is a marker of a “good” woman. Seeing these sinful women so visually defined by their hair would assign them a label of “sinful.” (9) The regulation of sexual punishment centered around the hair of sinful women in the fresco echoed the real-life regulation women endured every day.

In addition to having long, loose hair, Taddeo’s women also appear to have reddish blonde hair. The mixing of blond with red proffered two sets of negative significations: blonde with the erotics of poetic artifice and red with additional ideas of wildness and sin. Many Early Modern poets created the formulation of their own poetic beauties from Petrarch’s stylistic descriptions of Laura. (10) Over time, a portrait of the poetic beloved emerged from the ornamental vernacular tradition of Petrarch: long blonde hair, high forehead, delicate features, and a pale but lightly flushed complexion. (11) It is this aesthetic ideal that enthralled the poet and drew him in. The power of a woman’s beauty held in it the ability to create love and desire. Painters depicted real, mythological, and biblical women as these blonde poetic beauties, attempting to portray a figure’s inner beauty through outward visual attributes outlined by the poets.(12) Indeed these ideals proved to be extremely widespread, as fifteenth-century preachers became increasingly critical of women paying too much attention to appearance, as they sought to emulate this popular poetic ideal. (13)

Polemon of Laodicea, a second century Greek philosopher whose treatise on physiognomy survives in a fourteenth century Arabic translation, assigned certain characteristics to people having red or reddish colored hair:

“As for red hair that turns towards whiteness…it indicates a lack of understanding and knowledge and an evil way of life, so be very sure about this…As for ugly red hair, I do not praise it, nor do I praise its owner. You will often see hair that is redder than these, and their character resembles that of animals. In them is a lack of [modesty] and a love of covetousness.” (14)

Polemon was not alone in his distrust of red-haired people. In Physiognomics, attributed to Aristotle, the author, in his comparison of bodily characteristics to animal qualities, wrote “the reddish [haired] are of bad character; witness the foxes.” (15) Polemon’s tirade inferred moral characteristics based on the color of one’s hair. His negative feelings about red hair were due to a perceived character fault that was inherent in redheads: that they are incapable of control and thus are overtly greedy or desirous. (16) In Taddeo’s “Gluttony,” two women, alongside noblemen and a friar, sit at a dinner table, restrained by snakes and forced by demons to stare at food that they are unable to eat [fig. 17]. The reddish blonde hair of the woman on the left hangs long and loose. It frames her bare breasts, drawing attention to her sinful nakedness. In “Lust,” a woman on the left grimaces as her breast is groped by a dog-like demon who has his leg and arms wrapped around her [fig. 10]. Another woman, marked “adulteress” by a label above her head, is in the process of being whipped by a demon. Both women appear to have long reddish blonde hair and are punished in contrapasso. A sexual sin begets sexual punishment, exemplified by the women getting groped and whipped. Taddeo transcribed warnings about sexual punishment and sinful nature within “Lust” by conflating and applying the established sexual undertones inherent in contrapasso and red hair imagery onto the bodies of his punished women.

The reddish-blond hair of these female figures only served to increase the negative associations that viewers were meant to feel when viewing the fresco. Loose red-blond hair held negative connotations that symbolized a lustful person drawn to an evil, overtly desirous nature. Taddeo thus ensured that a message of sexual caution would be delivered to his viewers by emphasizing the sinful and lustful nature of the punished women through the depiction of these attributes.