Medieval Understandings of Pain and Punishment

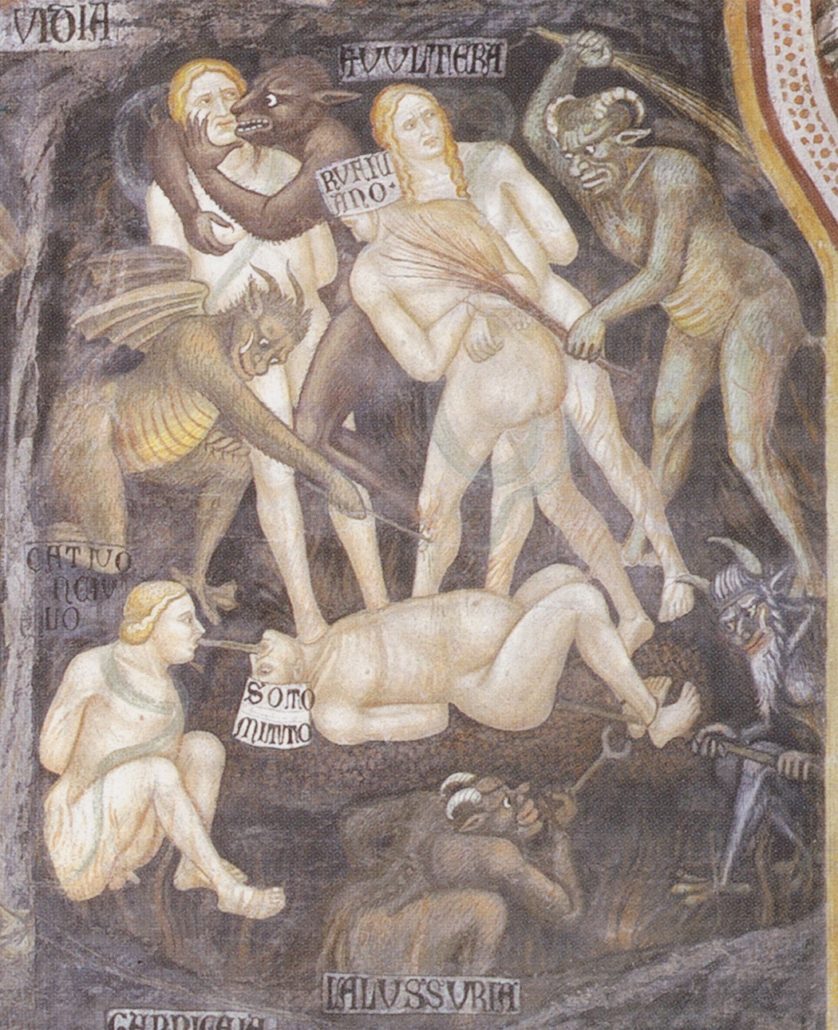

A defining aspect of the Collegiata Hell is its preoccupation with female sexual torture. Explicit episodes of torture appear throughout Hell, including a mounted woman whose torturer pushes his tail between her buttocks [fig. 6], a woman whose genitals are being disfigured by a female demon [fig. 7], and a long-haired woman who is groped by a demon as she bites her own hand in a show of wrath [fig. 8]. This section of the capstone will attempt to analyze and situate this imagery within the context of medieval understandings of pain and punishment, and the discussion of female sexuality introduced above.

Popular scholastic theology of the late Middle Ages taught that pain was a quality of the soul. (1) William of Auvergne, discussing the treatment of the soul in Hell, wrote:

“Therefore the human soul is only witness to its burning, since it has no heat in it … Why would it be wonderful, given that the fire burns in it [soul] purely by force of imagination, and the soul judges itself to be burning, for imagination is closer to the soul’s substance than the senses and is purely spiritual…? This appears so to [the soul] because of the extremely strong conjunction and union between it and the body, and thus it seems to it [soul] and it [soul] considers itself suffering what the body suffers, as it is not only [the soul that is] in the body, but the body, as many philosophers say, is rather in [the soul]….it is not the soul that really suffers from these passions as though they were its own [soul’s], but rather as empathizing with those of another [body].” (2)

To William of Auvergne, the unbreakable body/soul connection allows the soul to feel the pain the body endures, not through an actual physical affliction, but instead through a demonstration of empathy and spiritual torments. Even after death, this connection between the two was believed to exist. Building upon the thoughts of Augustine, Medieval theologians and scholars wrote that as postlapsarian humans, carnal bodily passions brought pain. This pain could require no external stimulus, instead it emerged from the soul. Esther Cohen wrote that “apprehension was the foundation of sensation, and if the soul in hell perceived itself as suffering, it did in reality suffer.” (3) The belief in the corporeal soul allowed preachers to bring the more abstract concepts of infernal suffering into tangible somatic terms that would allow the congregation, who experienced bodily pain, to feel more closely the threat of physical pain that awaited them in hell.

[Fig. 9] The Unicorn Purifies the Water (from The Unicorn Tapestries), Wool warp with wool, silk, silver, and gilt wefts, c. 1495-1505, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

In the San Gimignano fresco, demons use a multitude of weapons and tools to inflict pain onto sinners, including saws, whips, axes, knives, and more. In one detail, a group of demons torture a woman, utilizing multiple forms of physical torture [fig. 7]. A female demon pushes a unicorn horn into the genitals of a long-haired female sinner, in a possible condemnation of lust in the context of lesbianism. Unicorns in the early Middle Ages came to be seen as a symbolic allegory for Christ and the Incarnation, as well as female chastity. The second century Physiologus details that only the lap of a pure virgin could capture the beast. Centuries later, Gregory the Great in Commentaries on Job described the unicorn as a ferocious beast who is quelled by the Virgin Mary’s bosom, thus the ancient capture of the unicorn became a Christianized allegory of the Incarnation, and female virtue. (4) In the 13th-14th centuries the beast was transformed into a symbol of the love-sick courtly poet. (5) A late 15th century tapestry, The Unicorn Purifies the Water (from the Unicorn Tapestries) depicts a group of huntsmen watching a unicorn as it grazes within a hortus conclusus [fig. 9]. The gaze of the men transforms the image of the unicorn into a symbol of the courtly beloved, waiting to be ensnared in the traps of the courtly poet. Simultaneously, the hortus conclusus symbolizes the chastity linked to the Virgin Mary and Christ through the early Medieval understandings of the creature. (6)

In Taddeo’s infernal scene, the unicorn horn transforms into a bestial representation of the courtly love and female chastity long associated with it. Wielded by the only female demon in the fresco, the horn also represents a condemnation of lust through the evocation of lesbianism, which will be expanded upon in a later section. Similar to the tripartite laboring Satan also discussed in a later section, the unicorn horn as a torture device is meant to be a demonic parody of the divine and an inversion of its traditional connection to female chastity. An inversion of the female chastity associated with the beast, the unicorn horn also acts as an admonition of female same-sex desire. Through this motif, Taddeo communicated the point that if taken too far, vain concern with courtly beauty could be detrimental to the moral topography of women, leading to licentious behavior. The punishment of the woman is emphasized by the multitude of demons torturing her. Her agony and terror is made all the more visceral due to the associations prompted by the depictions of methods of public torture consistent with contemporary judicial punishments, which would have strengthened the associations between sexual transgression and severe punishment for viewers.

Samuel Edgerton, in a study of Florentine punishment during the Renaissance, analyzed various methods of punishments inflicted upon convicted criminals. He described punishments of diminutio capitis, which included public shaming and humiliation that often coincided with the crime committed. (7) Upper-class transgressors, with respect and monetary investments at stake, felt this public humiliation particularly strongly. Edgerton wrote that even as they mocked these transgressors, medieval Italians feared that one day, in hell, that humiliation could be their own. (8) Attendees of the Collegiata surely would have made the connection between the public humiliating punishments they witnessed on the streets of Tuscan towns and the sexualized punishments on the walls, which were then made public through their placement in a church central to the city. A painful facet of the punishment of the fresco’s sinners was not just the physical torture they endured, away from the grace of God and presence of Heaven; it was also the public presentation of their shame and sin.

Taddeo’s inclusion of this visceral punishment is purposeful. Scott Nethersole argued that violence was culturally constructed, in that peoples’ perceptions of violent visuals is dependent upon their cultural background. (9) For the medieval Tuscans who experienced the governmental public presentation of violent criminal punishments, violence had a didactic character that communicated ideas of proper behavior through the threat of punishment. (10) Violence was communicative, a form of language exhibited by the agents of the perpetuation of violence. (11)

In Taddeo’s Hell, bodies are punished in a multitude of ways. These bodies are marked as deviant and sinful, both by titulus and their nakedness, and then displayed prominently. In “Lust,” a woman marked “adulteress,” stands behind a man titled “ruffiano (pimp)” [fig. 10]. The male pimp holds his hands behind his back and hangs his head down in a show of shame, as a green, horned demon whips his back with a whip made out of wood branches or grass. The man’s torso twists forward, as if he is attempting to defend himself from the demon’s assault on his back, while his gaze is directed at another demon prodding his shin with a sharp object. The flogging demon holds another whip in his opposite hand, which the “adulteress” stares at in apprehension. The man below him labeled “sodomite” lies horizontally as a bearded demon inserts a stake into his anus and out through his mouth. Contorting his face in agony, the man raises his feet up in shock and pain, as another demon approaches his ankles with a pincer tool. Although not explicitly punished in this way, sodomy was an act that garnered extreme concern in canon and civic Medieval law. (12) A physical expression of sexual desire that had no chance of leading to procreation, it was mentioned by both theologians and lawmakers as a sinful, punishable offense. (13)

[Fig. 10] Taddeo di Bartolo, Lust, fresco, c. 1410-1420, S. Maria Assunta, Collegiata, San Gimignano.

The sin of these figures are communicated through the presentation of punishment. Based upon the teachings of the church, medieval Italian statutes began to convert ‘sins’ into ‘crimes.’ (14) The complicated and encompassing sin of lust was condensed into recognizable criminal acts. The presentation and public punishment of deviant bodies had an echo in the contemporary punishment of criminals in late medieval Tuscany. Mann, investigating the penal codes of San Gimignano, found that criminals were punished with permanent punishments: thieves were branded on the forehead, the impure were burned, etc. (15) These punishments marked the body in ways that were permanent and prominent, denoting them publicly as criminal and leading to social and economic repercussions in the future. (16) Similar to Edgerton’s findings in Florence, public humiliation and shaming was a form of punishment in of itself for the Sangimignanesi. The public nature of government mandated torture-as-punishment, in addition to marking the body as criminal, over time would show Italians that torture was a suitable penalty for misdeeds, providing the societal framework for depictions of hellish punishment. Hell’s moral message has an impact on the viewers because of the real-world association between criminality and public punishment. Inscribed on the wall in fresco, these sinner’s punishments are public forever, an extreme adaptation of the presentation of criminals in the streets of Tuscany.

(1) Esther Cohen. The Modulated Scream: Pain in the Late Medieval Ages. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010. 176.

(2) Ibid. 184.

(3) Ibid. 184.

(4) Jenny Davis Barnett, “(Re)Visions of the Unicorn: The Case of Scève’s Délie (1544).” Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 7, 2 (2020): 94-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol7/iss2/3

(5) Barnett, 97.

(6) Barnett, 101.

(7) Samuel Edgerton, Pictures and Punishment: Art and Criminal Prosecution during the Florentine Renaissance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985. 65.

(8) Edgerton, 66.

(9) scott Nethersole, Art and Violence in Early Renaissance Florence, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. 19.

(10) “Violent acts had an effect on the people who saw them- people who were themselves subject to the invisible, ‘violent’ structures of Florentine society and they responded to them… Violence was a form of communication, a type of language.” Nethersole, 19.

(11) Nethersole, 19.

(12) Nicolas Davidson, “Theology, Nature, and the Law: Sexual Sin and Sexual Crime in Italy from the Fourteenth to the Seventeenth Century,” in Crime, Society, and the Law in Renaissance Italy, edited by Trevor Dean and K.J.P. Lowe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994: 74-98.

(13) “Although this term could denote a wide range of prohibited sexual behviors deemed “contrary to nature”- so called because they did not lead to procreation, the sole “natural” purpose of sex according to Catholic dogma- it usually referred to sex between males,” in Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. 3.

(14) Davidson, 96-97.

(15) Mann, 418-19.

(16) Mann cited book three of the Communal Statues of 1255 as describing specific punishments for various crimes, such as flogging for heretics, a branded forehead for thieves, and a contrapasso burning for arsonists. In addition, the Ardinghelli family was convicted of treason and the members’ crimes were stated orally after which they were publically decapitated on the steps of the Palazzo Comunale, which is south-side adjacent to the Collegiata (Mann, 418).