Progym: Chreia

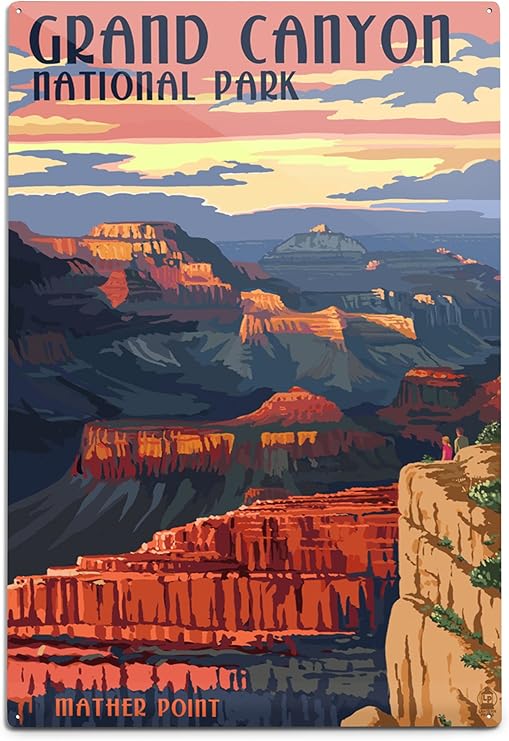

Frow’s writing highlights an idea that has seemed to linger at the back of my mind, though I couldn’t ever have put a finger on. Why do we travel? Culturally, I mean. It seems as though we are all in search of something, thinking that each trip should fulfill something within us, that each moment away from home should be a new page of our enlightenment. Frow takes a spin on this, saying that it in fact nostalgia that drives us, be it of a real historical period, or because of some feeling that a location is more wholesome, enlightened, or real.

“Nostalgia for a lost authenticity is a paralyzing structure of historical reflection,”

he writes, and this reflection leads us far and wide to find authenticity (135).

Frow asserts that nostalgia is an essential part of the tourist experience, in large part because it is central to our modernity. He writes that modern society at large, though often not even knowing it, is constantly longing for some lost, fictional past in which things were better. We long for “simpler times” indicated by childhood or happy days, and we think that somehow we have collectively undergone some kind of cultural decline. For example, every election cycle you hear calls that “oh this could never be worse,” or “I’ve never seen something like this,” and people long for the Obama or Reagan or Kennedy years when things were better, easier, or simpler, when in fact you heard the same calls at those times. It is this kind of eternal nostalgia, Frow says, that contributes to our tourist culture.

In his writing, Frow briefly references the popular idea of traveling for exoticism. The idea is very similar to his concept of traveling for nostalgia, in that from both perspectives we are in search of something as travelers. Both, to some extent, seek authenticity: something that is authentically foreign and exotic, or something that is authentic because of its relation to a better era. We may also think of traveling for the exotic as a kind of nostalgia, as we ride the gondolas in Venice or the tuk-tuks in India because they are both foreign and almost from another time from our Western perspective. The two ideas are not contradicting, but rather reinforce each other.

The souvenir, Frow says, is a prime example of nostalgia in travel. He says,

“the souvenir has as its vocation the continual reestablishment of a bridge between origin and trace… it works by establishing a metonymic relation with the moment of origin” (145).

We are so attached to this kind of nostalgia, that not only do we travel to fulfill our desire for it, but we must also buy tokens to remind us of our journeys to do so, to satisfy our following nostalgia for the trip itself. This is almost a kind of cycle of nostalgia, and it is a perfect example of the travel industry capitalizing on this concept. I, for example, traveled to my hometown of Green Bay driven by nostalgia and then bought a t-shirt in anticipation of future nostalgia for that trip; the same can be said of my trip to Germany, I traveled there almost for a kind of cultural nostalgia for the Old World, and I returned with beer-hall coasters.

Frow’s thesis in this piece represents the most convincing argument for why we travel that I have read thus far. Nostalgia is abundant in our culture, and the more I consider it the more I see it around us. It is no doubt then that we would choose our destinations based on nostalgia. Few people choose to travel to brand-new landmarks, because they do not have the cultural history to make them relevant, and many popular new landmarks are built with some kind of historical grandeur in mind. Frow’s argument seems to be the most logical conclusion based upon this. We don’t leave behind our culture of nostalgia when we travel, but rather our travel is one output for this nostalgia.