Environmental Justice History

In further determining the extent to which PFAS is an environmental justice issue, an examination of a past case within Washington, D.C. provided context into the environmental justice landscape and a reference point for our research.

Lead Contamination within Washington, D.C.

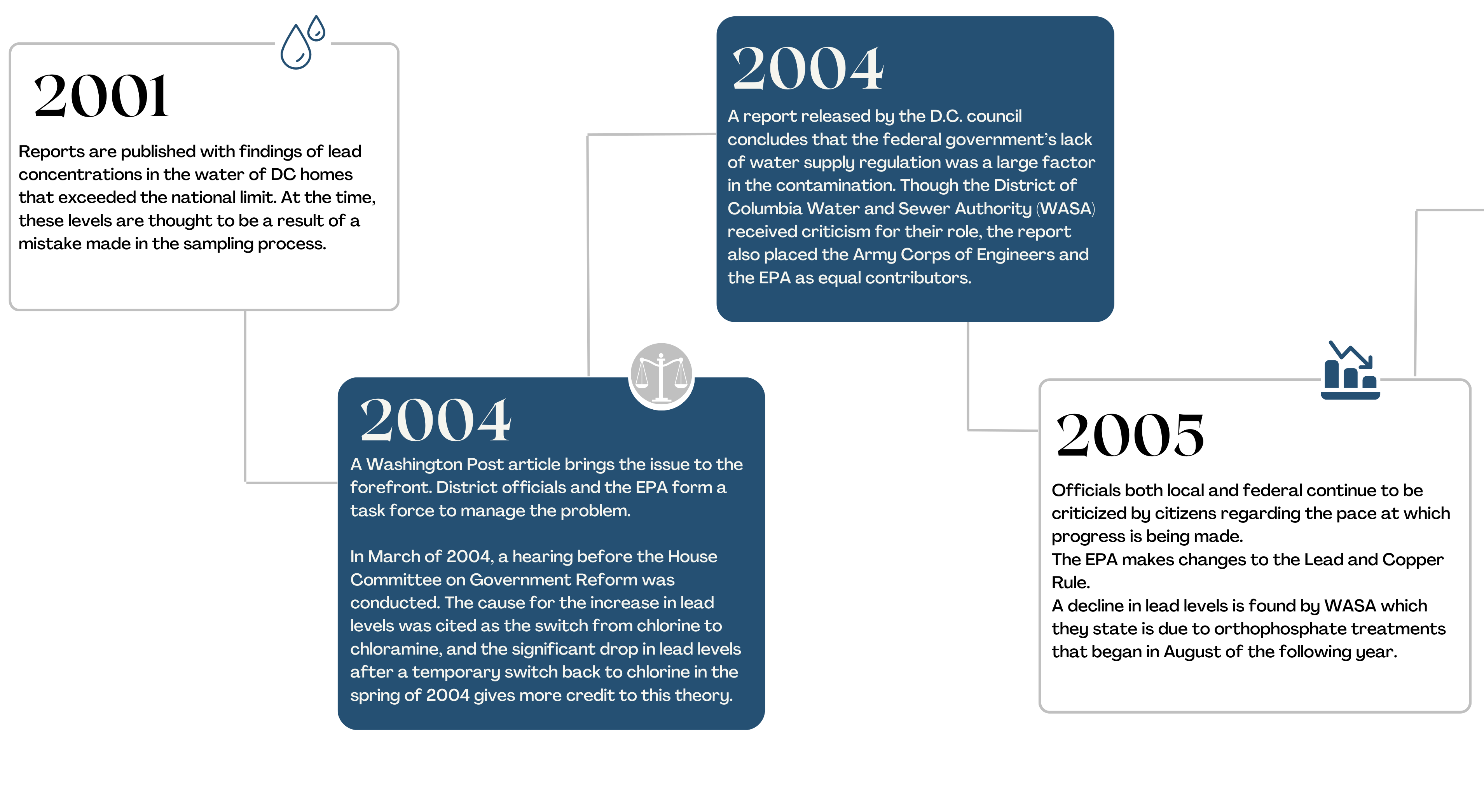

The rise in contamination occurred in the early 2000s, with the first reports acknowledging the spike in 2001. In the decades prior to this, lead contamination had been on the decline due to improvements in infrastructure. The high lead concentration levels found in the drinking water was an unexpected consequence of trying to reduce halo-methane compound levels, as the switch from chlorine to chloramine changed the chemical properties of the water.

High lead concentrations continued through 2004 when the issue is brought to the public, and the Water and Sewer Authority (WASA) began zinc orthophosphate treatments in August of that year. This treatment was effective in changing the water chemistry.

By 2006, the EPA was able to reduce its oversight over WASA since the lead levels in D.C. drinking water had remained under the national standard for a year.

A Washington Post article in 2004 brought the issue to the public. In response, district officials and the EPA created a task force to investigate and manage the issue. In the same year, The Water and Sewer Authority (WASA), Army Corps of Engineers and the EPA received criticism for a lack of water supply regulation in a report made by the D.C. council. There was also criticism from activists towards government officials that progress was not being made fast enough. In response to the public, the EPA made changes to the Lead and Copper Rule that added additional monitoring for disinfection profiling.

Though this issue was mainly centered around water contamination, it subsequently raised public awareness to the current danger of lead exposure from dust and paint chips, as older homes with lead service lines were more likely to also have lead paint. Children were the main concern of experiencing this exposure, as a correction to the 2004 CDC report revealed that more children within Washington, D.C. were affected by the drinking water contamination than initially documented.

This awareness led to an improved lead law found in the DC Lead Hazard Prevention and Elimination Act of 2008, later amended in 2010.

From 2000-2004, around 42,000 children under 2 years experienced lead exposure through water contamination in Washington D.C.

As of 2018, there are more than 20,082 “identified” lead pipes both full and partial, as well as 16,276 lines are still categorized as “unknown”.

Present Day Impact

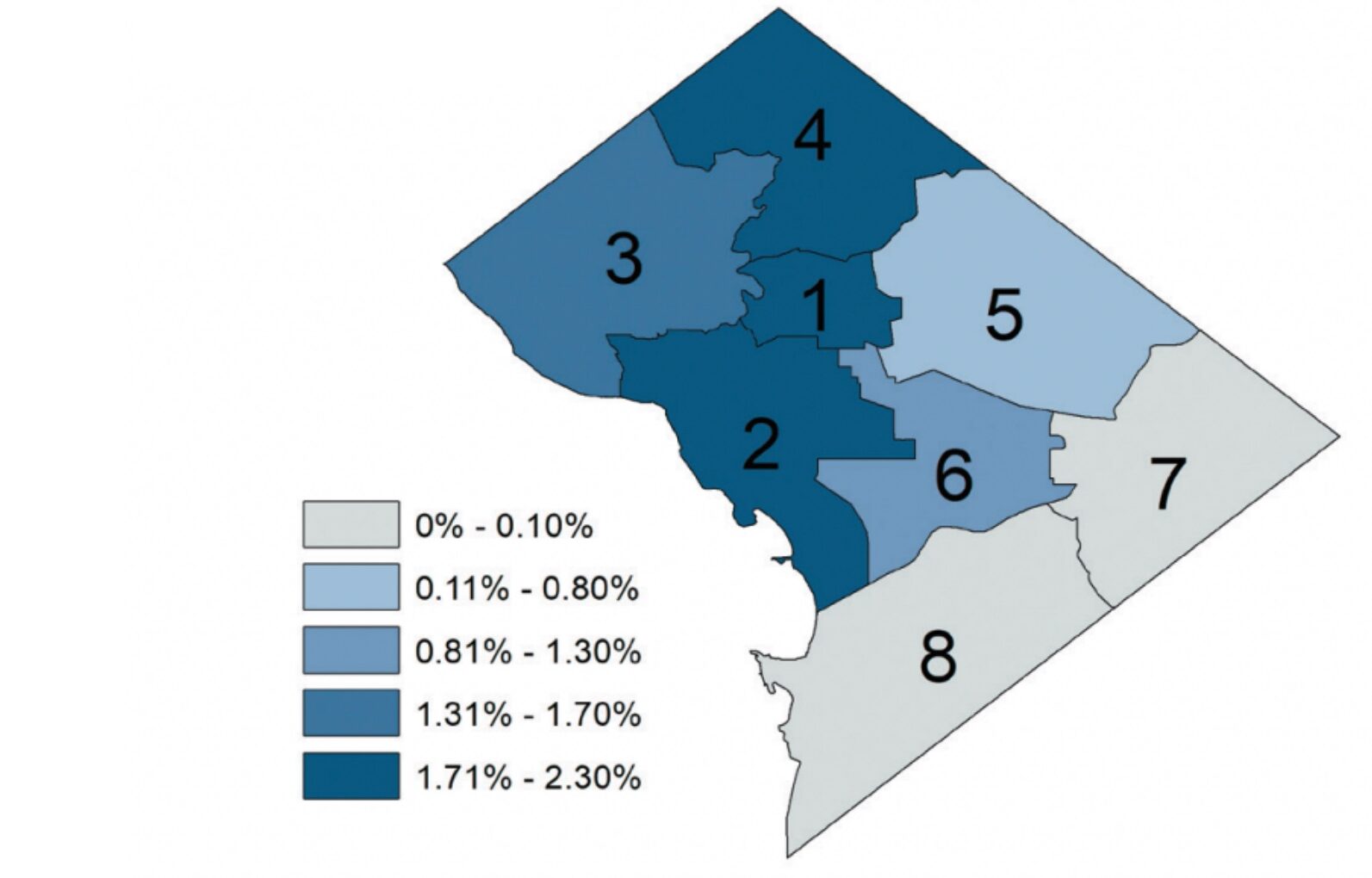

At the time of the initial spike, lead service pipes were in every ward of the city, with little variation between neighborhoods, and thus the water contamination affected the majority of the city.

Since then, regulations from D.C. have been put in place to replace lead service lines that are on public property, but the cost falls on homeowners once the pipes cross into private property.

Within Washington D.C, this has created a disparity between wards, as more affluent wards contain less lead pipes and thus the residents within the area are at less of a risk of lead exposure

In analyzing partial and full lead service line replacements in D.C. from 2009-2018, it was concluded that there were lower rates of service line replacements from wards that have a lower median household income and a higher number of residents who identified as African American/Black.

The wealthiest wards had a rate of service line replacement at 66%, while the wards with the lowest income only had a rate of replacement at 25%.

The maps below provide a visual insight into the disparities of lead service line replacements between neighborhoods in D.C.