Contemporary Western Death-Culture: What Our Cemeteries Say About Us

Trent Burns

You are going to die. Death is, after all, universal; it transcends social, ideological, and geographical differences. Despite this, each culture has a unique, and sometimes deeply contrasting, attitude towards mortality. As Western culture has evolved, so have its customs surrounding death. In her dissertation, “Death Perception: Envisioning a Cemetery Landscape for the 21st Century,” Erin Sawatzky identifies a historical pattern in which so-called Western “death-culture” fluctuates between two main extremes: necrophobia and necro-romanticism. Necrophobia, the extreme fear of dying and dead bodies, is a term applied to attitudes that reflect an overall cultural stigma towards death. In contrast, necro-romanticism refers to attitudes that embrace or are otherwise intrigued by death. Throughout its development, Western culture has moved back and forth across Sawatzky’s hypothetical death-culture spectrum, and has illustrated its boundaries with these two opposing attitudes. History provides different reasons for Western attitudes to shift, but the polar ends of the spectrum remain largely the same. The cycle appears to have developed so that death is alternatingly feared and romanticized. The most tangible examples of these shifting attitudes are cemeteries. Their physical appearance and roles within communities can be highly indicative of a society’s death-culture.

In Western culture, burial grounds have long reflected social attitudes towards death and memorialization. Their surroundings, proximity to communities, public access parameters, and policies regarding memorials all illustrate Western views throughout history. In particular, shifts in cemetery policies may also be examined as a reflection of cultural attitude; cemeteries can be viewed as sacred, closed spaces, or as romanticized green spaces that the community can use for a variety of purposes. Sawatzky looks at a broad range of historical eras and movements to trace major shifts in Western attitudes, including early Christian attitudes and continuing up until post-WWII views. Her argument for a cyclical “pendulum pattern” is convincing, but her research stops short of identifying where exactly in the cyclical pattern contemporary Western attitudes towards death fall. In the northwest United States, cemeteries are beginning to function as romanticized park spaces as well as burial grounds. However, this trend is still relatively new, and it remains unclear how far across Sawatzky’s spectrum current attitudes may shift. Locally, Oak Hill Cemetery provides an interesting case study for the evolution of contemporary death- culture, and stands at a crossroads of Western attitudes overall. It represents a park space in the urban environment of Washington, D.C. However, it remains a privatized cemetery and does not represent a complete shift towards multifunctional park spaces. Its management recognizes the value of romantic cemeteries, but is adamant about differentiating between ‘green space’ and ‘park space’ statuses. Oak Hill Cemetery is neither entirely necrophobic, nor is it entirely romanticized. However, its historic romanticism and growing trends of cemeteries as park space may indicate a broader movement of Western culture towards romantic attitudes once again.

Necrophobic attitudes towards death can be seen throughout history. A cultural fear of dying evolved from Christian beliefs regarding judgment in death. This eventually shifted Western attitudes towards widespread necrophobia that persisted for several hundred years. Sawatzky notes that, “As this fear of death increased, so too did the elaboration of rituals and of individual memorials in attempts to alleviate the dread and isolation now associated with death” (39). She also goes on to observe that this fear of death drove cemeteries closer to the church, and were responsible for a rise in the closing off of once public burial grounds (39). Death had become a malevolent entity, so cemeteries began to reflect this. Gothic architecture and gated spaces became more common, and burial grounds were often attached to churches in an effort to separate the dead from the general community. Elaborate memorials, tombs, and mausoleums all became reflections of the deceased. These outward signs of righteousness were, to the living, a triumph over death’s finality. Hierarchal memorials and burial sites represented a tangible legacy of those who had died, and artificially maintained the social gradient that death ultimately eradicates.

Contemporary science and medicine facilitated another shift in Western death-culture post WWII. Death became reduced to its most basic medical terms. Romantic ideals were eschewed in favor of more modern attitudes, which stripped death of mystery and of intimacy. Cremation provided an alternative to traditional burial that was viewed as cleaner, more modern, and a more efficient form of internment (Sawatzky 59). Fran Helner, in a piece for a Catholic periodical, highlighted and clarified the church’s growing support of cremation. In 1963, the Catholic Church began allowing cremations (Helner), and cremation rates rose dramatically throughout the 1970’s until the early 2000’s. By 2005, cremation accounted for roughly one third of post-mortem services in the US (“US Cremation Statistics”). This shift in favor of cremation reflects a significant turn away from romantic attitudes in the West. It marks a sterilization of post-mortem rituals, and a shift towards the secular image of death fostered by contemporary science. Sawatzky notes that, “Death became ‘medicalized,’ no longer considered natural, but rather a failure” (62). The advancement of medical science led to a new era of necrophobic attitudes in the West. As scientific advancements prolonged life, death resumed its role as an antagonist and as an “unnatural” event. Post-WWII attitudes reduced it to a failure on the part of the medical or scientific communities. Western culture began to accept that bodies are no more than organic matter that will rot once dead. The accompanying increase in cremation ceremonies illustrates its latent anxiety and subsequent desire for control – even over one’s decomposition.

Historically, romantic Western views of death can be traced back as far as ancient Greece, where it was viewed as an intrinsic part of life. Through rituals and memorialization the dead continued to play important roles in society long after their deaths. Sawatzky notes that this made cemeteries a romantic blending of two worlds: that of the living and that of the dead (17). This meshing of the living and dead, of space and place, illustrates some of the earliest romantic attitudes towards death.

However, normative attitudes like this would not be seen again until the Victorian Era, which once again romanticized the dead through complex systems of mourning and fanatical memento keeping. Victorian burial sites, despite moving away from densely populated areas in response to growing health concerns, were designed similarly to gardens. They represented communal space, and were well-landscaped with paths and plots balanced against dedicated green space (Johnson 787). This, coupled with extensive mourning protocols, publicized death during the Victorian Era and moved Western culture towards a far more accepting attitude of death.

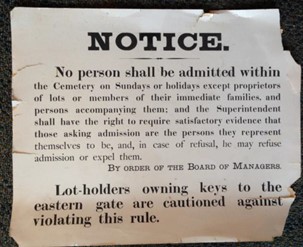

Fig.1. Period sign from the early 20th century indicate increasingly restrictive policies regarding the public use of Oak Hill land.

Some of these attitudes can be seen at Oak Hill Cemetery, which was founded in 1850 at the height of romantic death-culture. Situated on 22 acres of land overlooking Rock Creek, it was designed to intertwine its plots with the natural surroundings: a typical element of the 19th century Romantic Movement (“Oak Hill Cemetery History”). Anthropologist Thomas Harvey, in analyzing the romanticism of cemeteries, notes that cemeteries can be valuable wildlife habitats, historical locations, and green spaces particularly in urban environments (298). This is especially true of Oak Hill, since Washington, DC, has long been a city that recognizes the importance of park space. David Jackson, superintendent of Oak Hill Cemetery, concluded in an interview that 19th century attitudes towards burial grounds were fundamentally different than contemporary views. He notes, “There was more openness with regard to access within the cemetery…As late as the 20th century it was not uncommon for families to use cemeteries as a picnic area” (Jackson). He also recalls cemetery board meeting minutes in which the administrative board expressed concern over the use of cemetery grounds by non-owners. Jackson acknowledges the value of Oak Hill Cemetery as precious green space in a highly urbanized city, but does not see the cemetery being used as park space anytime soon. “Today’s views are just different,” he says, “it wouldn’t be the norm today” (Jackson).

Oak Hill’s reluctance to relax policies regarding public use may also stem from the difficulties of operating as both a cemetery and a park space. A general increase in property wear and tear, modified hours of operation, and vandalism are all factors that would make it difficult for Oak Hill to operate as park space even if it wanted to. This is not to say that Oak Hill Cemetery is an inaccessible green space; despite being a privately owned cemetery, its grounds are generally open to the public. A sign posted at its gate does, however, make the prohibition of leisurely activities clear; Oak Hill does not allow joggers, dogs, or bicycles on the property:

Fig. 2. Current sign from Oak Hill Cemetery.

While Oak Hill’s administration is reluctant to modify its policies, other cemeteries across the US are taking a much more active role in the so-called neo-romantic movement.

In his article, Harvey also examines similar historically romantic cemeteries in Portland, Oregon, saying “cemeteries have developed into multiple-use landscapes — contemplative parks, arboretums, recreational spaces…in addition to their function as burial grounds. They reflect our changing attitudes towards the cemetery landscape…” (Harvey 310). While Oak Hill Cemetery has yet to move this far forward in becoming a multipurpose space, its management remains firmly dedicated to the upkeep of the romantic landscaping and its presence as a park space within the community.

A small but growing movement on the west coast of the US may be indicative of a shift away from the current Western death-culture. A movement towards the romanticism seen in the 19th and early-20th centuries can especially be seen in the progressive Northwest. Harvey calls it a “romantic landscape park movement” (Harvey 302), and American Cemetery, a trade publication for cemetery owners and managers, calls it a “green” or “natural burial” movement. The central tenets of the movement include a desire to utilize cemeteries as park spaces, particularly in and around urban areas, as well as an increased sense of responsibility for the land on which the burial sites are located. While most Green Burial Council approved cemeteries in the US are located on the west coast, more are either being established or converted on the east coast every year (“Green Burial Council”). Despite approved burial grounds being established in neighboring states such as Virginia, DC law explicitly prohibits green burials within its jurisdiction (Jackson). This means that vaults and caskets must be sealed, eliminating biodegradable options that carry less environmental impact.

“There’s a definite movement, that’s undeniable,” says Oak Hill superintendent David Jackson, but he remains uncertain about the feasibility of neo-romantic cemeteries in DC. Unlike the sprawling, environmentally conscious burial grounds found near Portland, Jackson looks at the lack of space in and around DC as a central challenge for cemeteries looking to join such a movement. “Those cemeteries have the luxury of…having the space and the legislation to do that,” he says of neo-romantic cemeteries, “but it’s certainly the ‘in’ thing to do” (Jackson). If the romantic cemetery movement continues to spread across the east coast, existing legislation will need to be reevaluated in order to sustain such a shift in attitude. Harvey’s research shows that cemetery policies and related laws have already been reformed in areas like Portland, and east coat states are beginning to reflect a similar transition in death-culture.

One of the largest and most successful green cemeteries has embraced this highly romantic view of death, and aims to benefit its community as well as its clients. According to Kimberly Campbell, natural burial sites “put death in its rightful place,” and encourage a healthier attitude towards a natural life cycle (qtd. in “Green is Good” 22). Campbell’s family owns and operates one of the first green cemeteries on the east coast in South Carolina. The 74-acre property includes walking trails, and remains open for public use. Like other romantic park movement supporters, Campbell views this park space is valuable for cemetery visitors and members of the public alike; “Life in all its glory is going on around you” (“Green is Good” 23). Similarly, Harvey examines a romantic cemetery movement in and around Portland, Oregon, as an example of cemeteries embracing a renewed sense of necro-romanticism.

One cemetery in Portland, he notes, is open to pedestrians and bicyclists at virtually all times and provides a “commuting route that is safer and more pleasant than…the surrounding streets” (Harvey 304). While Oak Hill has not modified its policies to this extent, it still provides a valuable green space for its community. Pedestrians are welcome, and the landscaping of Oak Hill Cemetery continues to be one of the administrations central concerns. The scenic location and park space atmosphere of the cemetery may be indicative of a slow shift away from Sawatzky’s proposed necrophobic attitude that rose throughout the late 20th century.

Sawatzky’s research provides convincing historical evidence that Western death-culture has evolved along a single spectrum. This cyclical pattern alternately romanticizes and eschews death, with different historical events impacting the dynamic of each shift. What Sawatzky fails to identify, however, is what her research implies about a shift towards necro-romanticism in contemporary Western death-culture. In this respect, analyses like Harvey’s may indicate early signs of the next major shift in these views, at least in the US. What remains unclear about this new romantic movement is whether or not it will extend past its west coast roots, and if it will in fact mark the beginning of the next major attitude shift. Oak Hill Cemetery is historically romantic, but the direction it will go in remains somewhat unclear. For several reasons Oak Hill has yet to completely embrace a neo-romantic attitude towards death in so far as opening its space to the community around it. As its administration notes, it exists as a green space but not as a park space. In Sawatzky’s death-culture spectrum, Oak Hill falls somewhere in between the necro-romantic and the necro-phobic. However, its importance as a green space, if not a park space, makes it an interesting case study for where contemporary attitudes may move in the near future. Death-culture is in a continual state of flux, and the changing role of sites like Oak Hill Cemetery will ultimately say more about our future than the pasts they contain.

Works Cited

“Funeral Service Trends.” National Funeral Directors Association. National Funeral Directors Association, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

“Green Burial Council.” Finding a Provider. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2013. “Green Is Good.” American Cemetery (2013): 21-27. Print.

Harvey, Thomas. “Sacred Spaces, Common Places: The Cemetery in the Contemporary American City.” American Geographical Society 96.2 (2006): 295-312. JSTOR. Web. 14 Oct. 2013.

Helner, Fran. “Cremation: New Options for Catholics.” Catholic Update. American Catholic, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Jackson, David W. “Role of Oak Hill Cemetery.” Personal interview. 3 Dec. 2013.

Johnson, Peter. “The Modern Cemetery: A Design for Life.” Social & Cultural Geography 9.7 (2008): 777-90. Taylor & Francis Online. Taylor & Francis Group, 27 Sept. 2008. Web. 14 Oct. 2013.

“Oak Hill Cemetery History.” Oak Hill Cemetery. Oak Hill Cemetery, n.d. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

Sawatzky, Erin. Death Perception: Envisioning a Cemetery Landscape for the 21st Century. Diss. University of Manitoba, 2009. Ann Harbor MI: ProQuest, 2010. Sociological Abstracts. Web. 28 Oct. 2013.

“U.S. Cremation Statistics.” National Funeral Directors Association. National Funeral Directors Association, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Works Consulted

“Industry Statistical Information.” Cremation Association of North America (CANA). Cremation Association of North America (CANA), n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

“Oak Hill Cemetery.” National Register of Historical Places. National Park Service, n.d. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

Woods, Timothy J. “Death in Contemporary Western Culture.” Taylor & Francis. Taylor & Francis, 18 July 2007. Web. 27 Oct. 2013.

Wright, Elizabethada A. “Rhetorical Spaces in Memorial Places: The Cemetery as a Rhetorical Memory Place/space.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 35.4 (2005): 51-81. Taylor & Francis. Web. 17 Oct. 2013.