The Diversity Dilemma:

Examining the Relationship Between Diversity and Racial Capitalism on U.S. College Campuses

Cheyanne Cabang

Picture the ideal American college campus: substantial resources that expand beyond academics, students that engage in respectful intellectual debate, and—of course—a high level of diversity. Racial diversity in particular is long sought after in a time where social justice efforts have focused on decreasing the achievement gap among races. We are seeing great results: according to the National Center for Education Statistics, total college enrollment notably increased for Blacks and Hispanics from 2000 to 2016 (de Brey et al.). Additionally, U.S. News and World Report gives top tier universities, such as Stanford University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, and Columbia University, diversity index scores above 0.70 out of 1 (“Campus”).While minorities are increasingly enrolling in colleges, these institutions have been intensifying their efforts to address racial diversity.

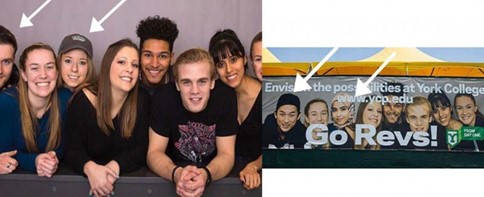

However, despite the promising statistics, not all universities truthfully reflect diversity on their campuses. One of the most notorious incidents of this is the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s promotional admissions booklet in 2000, where a Black student was photoshopped onto the cover in a sore attempt to showcase diversity. More recently, in a report by Inside Higher Ed, a similar incident happened in February 2019 when York College of Pennsylvania, a primarily white institution, Photoshopped a Muslim woman and Asian man onto a billboard with the headline, “Envision the Possibilities at York College,” in place of white students (see Fig. 1 below) (Jaschik). Outlined in that same report, in a study conducted of 371 college viewbooks, researchers found that “more than 75% of colleges overrepresent Black students in their viewbooks” (Jaschik). In both cases, students who are historically underrepresented became overrepresented as a consequence of college marketing tactics.

Figure 1 York College of Pennsylvania photoshopped billboard in 2019. Source: “When Colleges Seek Diversity Through Photoshop” (Jaschik)

In that case, where is the root of the problem? Why are colleges going through extreme, arguably unethical lengths to showcase diversity? How have national expectations and pressure for racial diversity in colleges affected the experiences of college communities? At what point does the desire for diversity and inclusion become thinly veiled racism?

While some believe that diversity in and of itself is a good thing, I assert that this is a problematic perception that fails to bridge the inequalities between races in our current society. Additionally, there is a misguided belief that the enrollment of a diverse student body is akin to inclusion in universities and the eradication of racism.

In this essay, I will examine why diversity is important to the U.S. as well as race-conscious admissions policies. I will also introduce the concept of racial capitalism and its contribution to the oppression of minorities. I will argue that the movement for increased diversity has created an oppressive culture of racial capitalism or “fake diversity,” in which institutions aim to capitalize off of racial diversity. I will specifically focus on U.S. universities partaking in these practices. Furthermore, I contend that due to the presence of racial capitalism, a diverse environment does not equal an inclusive community for minorities to thrive in and thus hinders their overall success and experiences within their respective institutions.

1. Dimensions of Diversity: Importance of Diversity in Higher Education

In popular conversation, most Americans are united in understanding the value of diversity; it is recognized that the immense racial, political, and religious diversity of the U.S. are part of what makes it an attractive country. But what is diversity, exactly? In order to take a more systematic approach to this issue, diversity must be defined. Social psychologists Unzueta and Binning define diversity as, “consisting of at least two distinct dimensions… (a) the numerical representation of underrepresented minorities in an organization and (b) the hierarchical representation of underrepresented minorities at specific levels of the organization’s hierarchy” (27). By defining one of diversity’s dimensions as the numerical representation of underrepresented minorities in an organization, Unzueta and Binning are referring to the importance of seeing diversity in numbers relative to the population’s percentages. Hierarchical representation refers to the various positions in which underrepresented minorities are represented in an organization. Both dimensions are equally important to consider. Diversity in the case of this essay refers to the first dimension of diversity: a proportionately diverse racial population, with a focus on diversity in higher education.

There are, of course, multiple and distinct parts of diversity such as socioeconomic status, cultural, religious, and political or ideological. However, racial/ethnic diversity is particularly important in higher education because of the correlation between race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. The American Psychological Association states, “Research has shown that race and ethnicity in terms of stratification often determine a person’s socioeconomic status. Furthermore, communities are often segregated by [socioeconomic status], race, and ethnicity. These communities commonly share characteristics: low economic development; poor health conditions; and low levels of educational attainment.” Socioeconomic status’s large determination by race and ethnicity speaks to the continued widening of the race gap in the conversation on the relationship between poverty and race.

In the article, “Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America,” Metropolitan Policy Program researchers Reeves, Rodrigue, and Kneebone examine poverty as multidimensional rather than being narrowly defined as a lack of income; multidimensional poverty encompasses low household income, limited education, no health insurance, living in a high-poverty area, and unemployment (2). Reeves, Rodrigue, and Kneebone also found that racial minorities, specifically Blacks and Hispanics, are at a disadvantage and minorities are more likely to experience at least one dimension of poverty than their white counterparts (7).

According to the same study, Hispanic adults are four times more likely than whites to experience being both low-income and having no high school diploma (17 percent vs. 4 percent), while Black adults are more likely than whites to experience both low-income and unemployment (13 percent vs. 6 percent), or low-income and geographic poverty (16 percent vs. 3 percent) (Reeves, Rodrigue, and Kneebone 10). The racial disparities mentioned above are reflective of the inequalities that exist within the deeply stratified U.S. society. Thus, it is imperative that we bring race and ethnicity into the conversation, particularly within higher education as educational attainment serves as an indicator of upward social mobility and a lack of such serves as a dimension of poverty.

2. Higher Education and The Racial Dilemma

Now that there is an understanding of racial inequalities within the U.S. society, we must narrow the scope and examine the inequalities that exist in the university. The racial dilemma in education was not abolished when school segregation was. Although minorities are no longer separate from their white counterparts in terms of accessing a higher education, it does not mean that they are equal. Today, minority students continue to suffer from racially charged incidents, discriminatory admissions practices, and alienation and subconscious segregation on college campuses across the nation.

In a New Directions for Student Services study conducted on campus racial climates, researchers Harper and Hurtado concluded that, “The themes of exclusion, institutional rhetoric rather than action, and marginality continue to emerge from student voices” (15). The article also touched on self-reports of racial segregation, notably among the fraternity row, where a Black student referred to his university’s fraternity row as the “Jim Crow Row” in which he was denied access to parties and other events on the probable basis of race (Harper and Hurtado 16). The university is often viewed as a microcosm of the larger society or communities they are a part of—if this is the case, race relations are of great concern as minorities are directly affected by campus racial climates.

However, race relations do not only affect minorities; they hold great potential to disrupt entire communities. Race on college campuses has served as a volatile and divisive issue for students, faculty, staff, and college culture at large. The most recent and notable racially polarizing event is the massive College Admissions Scandal. This scandal unveiled the powerful influence of wealth through the charging of high-profile, white celebrity parents who poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into forged extracurriculars and skewed test scores to buy seats into high-profile universities. The admissions scandal, coupled with Asian-American students filing a lawsuit against Harvard University to end affirmative action due to perceived discriminatory admissions policies, caused a nationwide spotlight to shine on the admissions practices of universities and the importance of considering race. Racial tensions in higher education continue to divide the larger community beyond the microcosm of college.

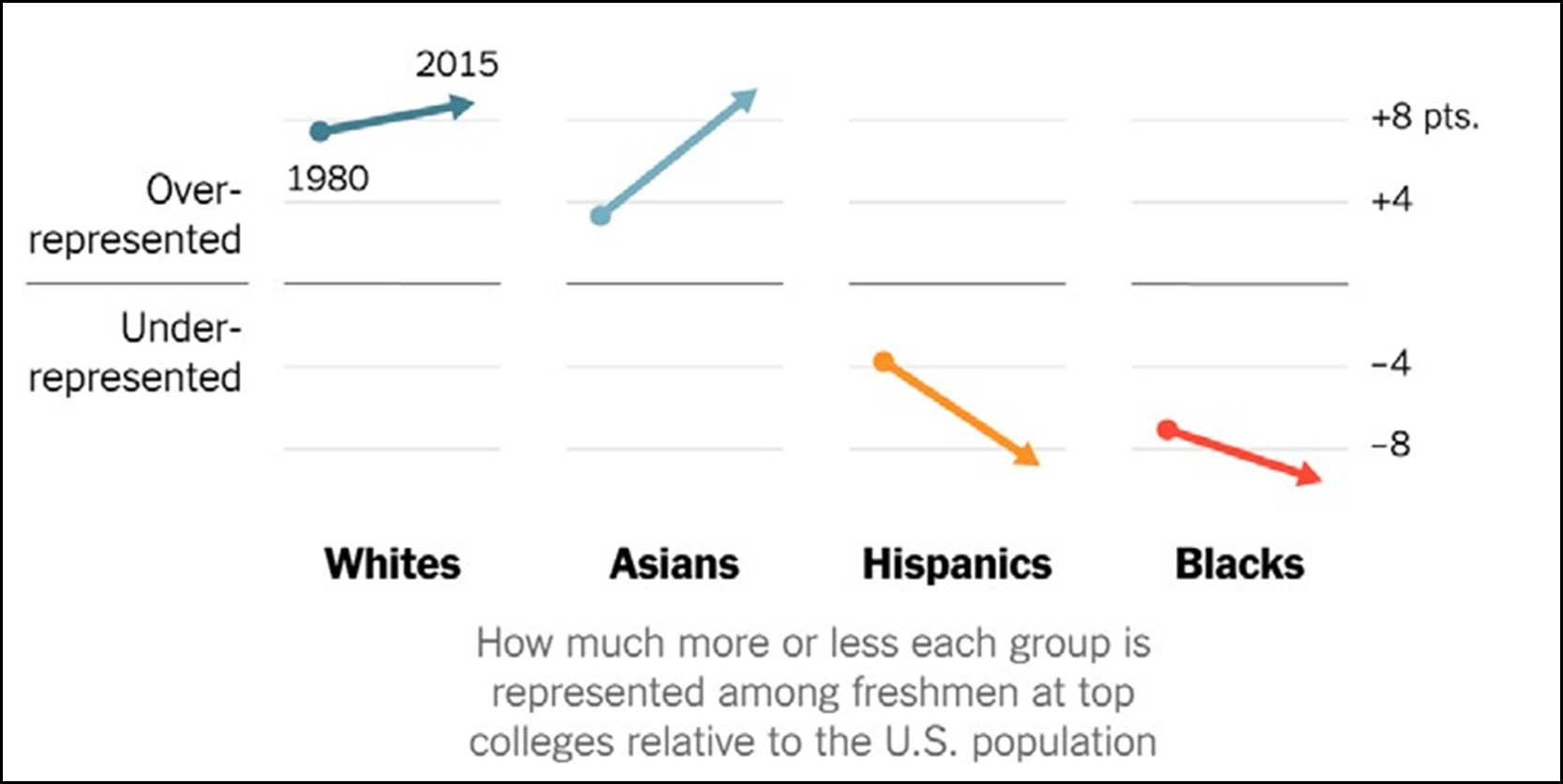

Regarding diversity in higher education, findings from The American Freshman Survey indicate that, “[At four-year universities nationwide], 79 percent of college freshmen are white, 12 percent are Black, and the Asian and Hispanic shares are roughly 5 percent each” (Espenshade 21-22). For comparison’s sake, when looking at racial disparities in the Ivy Leagues, Black students at Ivy League schools made up 9 percent of the freshman class in 2015 compared to the overall 15 percent of college-age Americans, marking Black students as underrepresented (Ashkensas, Park, and Pearce). Figure 2 below depicts changes in freshmen representation by race at top colleges relative to U.S. population from 1980 to 2015, courtesy of The New York Times. Both whites and Asians have become increasingly overrepresented as opposed to Hispanics and Blacks, who have become increasingly underrepresented.

Figure 2 Representation of college freshmen at top colleges relative to U.S. population, excluding international students and students whose race is unknown. Courtesy of The New York Times (Ashkensas, Park, and Pearce).

According to Farran Powell, a writer for the U.S. News, top colleges provide more resources and opportunities than lower-tier colleges with the potential to secure an above average salary post-graduation, regardless of discipline. Although Black and Hispanic students are underrepresented at top colleges, it does not mean they are any less academically capable than white and Asian students. However, as discussed above, structural inequality, low socioeconomic status, and higher risks of multidimensional poverty have caused this to be so.

3. Landmark Cases: Looking at Race in the College Admissions Process

In order to understand the beginning of the movement for increased racial diversity in colleges, we must examine how race has entered the national conversation, particularly in higher education, through landmark cases in the Supreme Court. Due to the historical underrepresentation of minorities in colleges across the nation, colleges have made efforts to prioritize a racially diverse student body. This consideration of race is known as affirmative action. The Legal Information Institute at Cornell identifies affirmative action as:

an active effort to improve employment or educational opportunities for members of minority groups and for women. [It] began as a government remedy to the effects of long-standing discrimination against such groups and has consisted of policies, programs, and procedures that give preferences to minorities and women in job hiring, admission to institutions of higher education, the awarding of government contracts, and other social benefits.

For decades, affirmative action has sparked debate concerning the fairness of such processes despite the intention to work towards a just society for historically underserved groups. This has led several cases to make their way up to the Supreme Court.

Listed as the first of such high-profile cases on Justia was Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978, when the Supreme Court ruled that race could be used as a criterion for admission in institutions of higher education, but invalidated racial quotas. This was in response to Alan Bakke, a white man who had applied twice to the medical school at the University of California-Davis and was rejected both times. As part of its Affirmative Action Program, The University of California-Davis reserved 16% of its admission spaces for minority applicants (“Regents”). However, Bakke protested that because his grades and test scores were higher than that of minorities who had been admitted, he had been discriminated against on the basis of race. Since then, it has been affirmed that “a diverse classroom environment is a compelling state interest under the Fourteenth Amendment” (“Regents”).

Moreover, other cases challenging affirmative action are Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) and Fisher v. University of Texas I and II (2013 and 2016), all of which reaffirmed the constitutionality of affirmative action under strict judicial scrutiny but discouraged race being the primary factor in which an applicant is accepted or rejected (“Affirmative”). In the case of Grutter v. Bollinger, the Supreme Court struck down the University of Michigan Law School’s policy of awarding points to students based on race (“Affirmative”).

Indeed, with race-conscious admissions policies receiving much public exposure, scrutiny, and debate, race has propelled itself into the national conversation. Affirmative action has been deemed constitutional due to the injustices and discrimination that minorities have faced and continue to face. The movement for diversity can be traced alongside this as people have begun to emphasize the importance of diversity and equity. The continued protection of racial diversity under the Fourteenth Amendment speaks to both the value of racial diversity in the U.S. and the beginning of the now-skewed race to recruit and sometimes overrepresent minorities on college campuses.

4. Racial Capitalism and Diversity as a Commodity

Although it was previously established that the nation is taking steps to increase and promote racial diversity in the workforce and in institutions of higher education due to race entering the national conversation, it is imperative to be aware of the existence of racial capitalism. An ironic consequence of the pressure for diversity has caused an undue shift in motive and practices for institutions as they begin to substitute the substantial benefits of diversity for appearances and numbers. In this way, the views of institutions and the general public on diversity have become problematic and concerning as they tiptoe the line between diversity and inclusion and racism.

A white man claims he can’t be racist because he has a Black friend. Marketing tactics for a new movie revolve around a token minority character. A university’s concerns about racial homogeneity getting in the way of prospective students’ admissions leads it to Photoshop a Black student onto an admissions pamphlet. These are all instances of racial capitalism.

Nancy Leong, a law professor at the University of Denver, defines racial capitalism as, “The process of deriving social or economic value from the racial identity of another person. A person of any race might engage in racial capitalism, as might an institution dominated by any racial group” (Leong “Racial” 2153). In essence, racial capitalism is the term used for commodifying diversity due to its inherent value in a society so preoccupied with increasing diversity. In popular terms, racial capitalism is referred to as “fake diversity.” Leong further states that, “While in theory any group might derive value from the racial identity of another, in practice, since white people are historically and presently a majority in America, racial capitalism most often involves a white person or a predominantly white institution extracting value from non-white racial identity” (Leong “Fake”). Here, Leong touches upon an important question: who does racial capitalism involve? Essentially, Leong speaks to the systematic and structural divide of power between whites and nonwhites in the U.S.

Racial capitalism is problematic because it is normally all show and no substance on the institution’s part. In the case of the Photoshopping incidents at both York College of Pennsylvania and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, minorities were used as a part of college marketing tactics to showcase a diverse social environment, when in fact the pamphlet did not accurately reflect the actual student demographic and thus overrepresented the minority populations shown.

Likewise, attempts of a similar vein are sometimes made with good intentions without regard to the consequences of such actions. Acts to increase and promote diversity should indeed be celebrated. However, the real problem lies within the motives and practices of institutions, particularly primarily white institutions, partaking in this. Diversity becomes viewed in the most short-sighted way: as a prized commodity and a display of numbers and appearances, rather than what it essentially is—a personal manifestation of identity. This definition of diversity is the reason why we seek to represent minorities numerically: their identities are historically underserved and we as a society must rectify the injustices and discrimination that structural and systematic inequality and racism has caused.

Furthermore, racial capitalism is much akin to darker times in U.S. history, where nonwhite people were assigned value based on their race and used as a commodity for white people, who were in power (Leong “Racial” 2154). Despite a different motive, the premise is the same: when institutions showcase minorities in a superficial manner, they are reaping the benefits of perceived diversity at the expense of both the minority or minorities shown and the experience of future minorities at the institution.

With “fake diversity” so prevalent, it is imperative to ask the administrators of universities if their perceived commitment to diversity is matched by success in enrolling and retaining underrepresented students. Because of the large socioeconomic inequalities that exist within the rhetoric for diversification, it is a given that universities hold the power to commit to diversity enough to work towards closing the racial gap in education.

5. A Change in Definition: Diversity versus Inclusion

The most obvious alternative to colleges falsely representing diversity is accurately portraying it. This is not just during the admissions processes; the enrollment of a diverse student body is but one part of the solution. As a society, outlawing segregation and discrimination and allowing for race-conscious and “holistic” admissions policies has not created equal educational opportunities. This is in light of problems beyond racial disparities in education to many persistent barriers to higher education such as an unequal K-12 educational or “feeder” system, highly inflating tuition costs, and weak college counseling. These barriers further stipulates the idea that our society still needs to address the plight of minorities, especially those who are low-income and/or may reside in areas with geographic poverty.

With this in mind, a better approach is considering what happens once the diverse student body is enrolled. How can colleges better support minority students and facilitate enriching learning experiences for the entire college community? The pressure for increased diversity has caused a misconception of what a diverse environment actually entails: inclusion. Marta Tienda, a Professor of Sociology at Princeton University, offers the definition of inclusion as, “organizational strategies and practices that promote meaningful social and academic interactions among persons and groups who differ in their experiences, their views, and their traits” (467). In essence, inclusive practices strives to embrace all members of a community while recognizing their differences as valuable to contributing to interact within the community. It is an ideology aimed at providing equal access to opportunities and removing barriers.

Nonetheless, it is important to distinguish between diversity and inclusion/integration. In the book, Defending Diversity: Affirmative Action at the University of Michigan, authors Gurin, Lehman, Lewis, Day, and Hurtado assert that, “The word diversity [is] somewhat one-dimensional, connoting [mainly]… racial heterogeneity… At least today, the word integration does a better job of capturing the special importance to our country of undoing the damaging legacy of laws and norms that artificially separated citizens from one another on the basis of race” (62). Thus, the point of distinguishing these two terms lies in the fact that the definition of diversity has been distorted. Diversity on its own does not guarantee the achievement of the goal for equitable educational opportunities. Because of this, fostering an inclusive environment through integration is necessary.

The Association of American Colleges & Universities’, “Committing to Equity and Inclusive Excellence: A Campus Guide for Self-Study and Planning” provides a framework for higher education leaders and campus educators across departments to engage in meaningful and needed dialogue, self-assessment, and action to begin to commit to the success and learning of all students. The guide pays special attention to historically underserved students in higher education, with racial minorities being one of many. The Association of American Colleges & Universities maintains that the commitment to inclusivity encompasses being aware of and evaluating current and future student demographics, committing to difficult but necessary dialogues about campus climates on both the institution’s end and students’ end with the goal of change and action, and investing in culturally competent practices. The guide emphasizes the importance of expansion— expanding opportunities, resources, and curriculums that commit to the success and representation of underserved students.

Indeed, commitment to diversity and inclusion makes a difference. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s, “Advancing Diversity And Inclusion In Higher Education: Key Data Highlights Focusing on Race and Ethnicity and Promising Practices,” “Students report less discrimination and bias at institutions where they perceive a stronger institutional commitment to diversity” (49). In a Science article titled, “Scientific Diversity Interventions,” researchers Moss-Racusin, Van Der Toorn, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham, and Handelsman suggest that leaders and faculties’ participation in diversity training and workshops can positively influence their behaviors and attitudes, most notably inclusive acting and teaching (615). In addition, resources such as alumni of color affinity groups and cultural organizations and clubs can contribute to the emotional wellbeing of students of color on campus (U.S. Department of Education 51). This is the difference between inclusion and racial capitalism: the substance and effort on the institution’s part is there and also transparent.

One example of a university implementing inclusive strategies is the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s I-Connect Diversity and Inclusion Workshop, which offers collaborative exercises and discussion for first-year and transfer students to build and enhance communication skills and students’ ability to collaborate in diverse environments (U.S. Department of Education 50). Georgia State University also has a Multicultural Programming Council, which is comprised of student leaders who “provide input on events and initiatives developed and supported by the Multicultural Center, as well as workshops, advisement, and funding to student groups” (U.S. Department of Education 51). Both universities referenced have demonstrated increased Black and Hispanic enrollment and graduation rates as well as the increased hiring of nonwhite faculty (U.S. Department of Education 52). A demonstrated commitment to diversity and inclusion on the institution’s part has significant benefits for college communities and combats the problematic perception that diversity on its own is beneficial. Indeed, inclusion and integration for minority students serves the greater purpose of bridging the racial gap in higher education.

Circling back to underrepresented college students overrepresented on viewbooks, we must recognize that race has become important in the national conversation. People are recognizing the importance of sustaining diverse environments of all kinds and has thus propelled fundamental changes to the way institutions handle diversity. In the case of institutions overrepresenting underrepresented students, particularly primarily white institutions, it perpetuates racial capitalism and solidifies the assignment of value to people based on race in the form of oppression that can be traced back to darker times of slavery in U.S. history. Because diversity doesn’t fully account for the goals of equitable access to educational opportunities, a better concept to strive for is the inclusion and integration of minorities in college environments to ensure a just society.

Therefore, it is up to us as consumers of similar marketing tactics and other showcases of false diversity to reject them and hold these universities accountable and ask them the harder questions: what efforts are they putting into motion to retain their minority students and get them to graduation? What inclusive practices have they propelled to encourage students to reap the benefits of diverse learning environments while discouraging racism, prejudice, bias, and discrimination?

If we remain satisfied with false representations of diversity, it paves the way for an era of complacency where we allow identities in power to continue to extract and assign value from those who do not have power. By accepting racial capitalism, we allow the oppression and commodification of nonwhite identities to continue.

Works Cited

“Affirmative Action.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/affirmative-action.

American Psychological Association. “Ethnic and Racial Minorities & Socioeconomic Status.” American Psychological Association. July 2017. www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/minorities.

Ashkenas, Jeremy, Haeyoun Park and Adam Pearce. “Even with Affirmative Action, Blacks and Hispanics are More Underrepresented at Top Colleges Than 35 Years Ago.” New York Times, 24 Aug. 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/08/24/us/affirmative-action.html

Association of American Colleges & Universities. “Committing to Equity and Inclusive Excellence: A Campus Guide for Self-Study and Planning.” AACU, 2015. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/CommittingtoEquityInclusiveExcellence.pdf.

“Campus Ethnic Diversity.” US News and World Report. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-universities/campus-ethnic-diversity

de Brey, Cristobal, Lauren Musu, Joel McFarland, Sidney Wilkinson-Flicker, Melissa Diliberti, Anlan Zhang. Claire Branstetter, and Xiaolei Wang. U.S. Department of Education. “Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018.” National Center for Education Statistics, February 2019. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019038

Espenshade, Thomas J. No Longer Separate, Not yet Equal : Race and Class in Elite College Admission and Campus Life. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Gurin, Patrick et al. Defending Diversity: Affirmative Action at the University of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Harper, Shaun R. & Hurtado, Sylvia. “Nine Themes in Campus Racial Climates and Implications for Institutional Transformation.” New Directions for Student Services., vol. 2007, no. 120, Jossey-Bass, 2007, pp. 7–24, doi:10.1002/ss.254.

Jaschik, Scott. “When Colleges Seek Diversity Through Photoshop.” Inside Higher Ed, 4 February 2019. www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2019/02/04/york-college-pennsylvania-illustrates-issues-when-colleges-change.

Legal Information Institute. “Affirmative Action.” Cornell University Law School. www.law.cornell.edu/wex/affirmativeaction.

Leong, Nancy. “Fake Diversity and Racial Capitalism.” Medium, 23 November 2014. medium.com/@nancyleong/racial-photoshop-and-faking-diversity-b880e7bc5e7a.

Leong, Nancy. “Racial Capitalism.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 126, no. 8, 2013, pp. 2153–2225., harvardlawreview.org/2013/06/racial-capitalism/.

Moss-Racusin, Corinne A., Jojanneke Van Der Toorn, John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham, & Jo Handelsman. “Scientific Diversity Interventions.” Science, vol. 343, no. 6171, 2014, pp. 616-616. doi: 10.1126/science.1245936.

Powell, Farran. “How Much Is an Ivy League Liberal Arts Degree Worth?” U.S. News, 10 September 2018. www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/paying-for-college/articles/2018-09-10/how-much-is-a-liberal-arts-degree-from-the-ivy-league-worth.

Reeves, Richard, Edward Rodrigue, & Elizabeth Kneebone. “Five Evils: Multidimensional Poverty and Race in America.” Economic Studies at Brookings Report, 14 April 2016. https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/five-evils-multidimensional-poverty-and-race-in-america/

“Regents of Univ. of California vs Bakke. 438 U.S. 265. Supreme Court of the U.S. 1978.” Justia. supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/438/265/.

Tienda, Marta. “Diversity ≠ Inclusion: Promoting Integration in Higher Education.” Educational Researcher, vol. 42, no. 9, Dec. 2013, pp. 467–475, doi:10.3102/0013189X13516164.

Unzueta, Miguel M., & Kevin R. Binning. “Diversity Is in the Eye of the Beholder: How Concern for the In-Group Affects Perceptions of Racial Diversity.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 38, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 26–38, doi:10.1177/0146167211418528.

United States, Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Developoment. “Advancing Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education: Key Data Highlights Focusing on Race and Ethnicity and Promising Practices.” Nov. 2016. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdf

Works Referenced

Biskupic, Joan. “Federal Judge upholds Harvard’s admissions process in affirmative action case.” CNN, 1 October 2019. www.cnn.com/2019/10/01/politics/harvard-affirmative-action/index.html.

Bruni, Frank. “The Lie About College Diversity.” The New York Times, 12 December 2015. www.nytimes.com/2015/12/13/opinion/sunday/the-lie-about-college-diversity.html.

Courteau, Rose. “The Problem With How Higher Education Treats Diversity.” The Atlantic, 28 October 2016. www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/10/trading-identity-for-acceptance/505619/.

“Grutter v. Bollinger.” Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/2002/02-241.

Hirschman, Daniel, & Ellen Berrey. “The Partial Deinstitutionalization of Affirmative Action in U.S. Higher Education, 1988 to 2014.” Sociological Science, vol. 4, 2017, pp. 449-468. doi:doi.org/10.15195/v4.a18.

Hulse, Nia E. “Preferences in College Admission.” Society, vol. 56, 2019, pp. 353-356. doi:doi.org/10.1007/s12115-019-00380-7.

Kershnar, Stephen. “Race as a Factor in University Admissions.” Law and Philosophy, vol. 26, no. 5, 2007, pp. 437–463. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27652626.

Lewis, E., Lehman, Jeffrey S., & Gurin, Patricia. Defending Diversity: Affirmative Action at the University of Michigan. University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Lynch, Matthew. “Diversity in Higher Education: The Issues Most People Don’t Think About.” The Advocate, 20 December 2018. www.theedadvocate.org/diversity-in-higher-education-the-issues-most-people-dont-think-about/.

McLaughlin, Elliot C. & Burnside, Tina. “Bananas, Nooses at American University Sparks Protests, Demands.” CNN, 17 May 2017. www.cnn.com/2017/05/17/us/american-university-bananas-nooses-hate-crime-protests/index.html.

Melamed, Jodi. “Racial Capitalism.” Critical Ethnic Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2015, pp. 76–85., doi:10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076.

Prichep, Deena. “A Campus More Colorful Than Reality: Beware That College Brochure.” NPR, National Public Radio, 2013, www.npr.org/2013/12/29/257765543/a-campus-more-colorful-than-reality-beware-that-college-brochure.

“Racial Awareness.” Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. Yale, 2020. poorvucenter.yale.edu/RacialAwareness.