Since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011, Libya has experienced the collapse of a dictatorship, mass population displacement, and the powerful rise of homegrown militias, terrorist groups, and regional tribes who continue to scramble for power and legitimacy despite international support for the Government of National Accord (GNA).

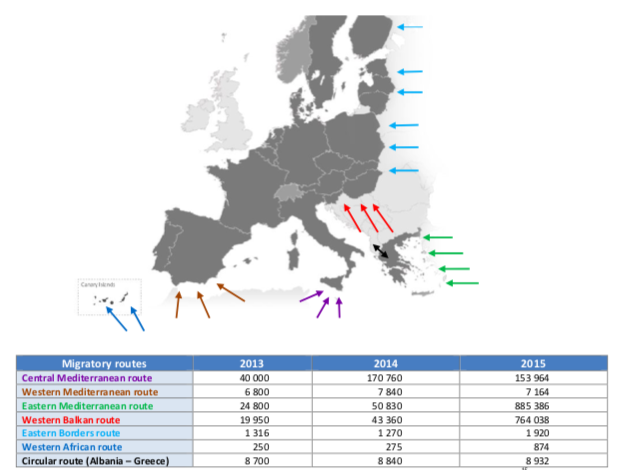

Before and after 2011, Libya’s role as the final gateway in the most populous migratory route from Africa to Europe has not changed. Migrants originating in countries as geographically distant as Senegal, Mali, Somalia, Eritrea, Syria, Chad, and Yemen all make use of the migratory funnel through Libya.

Libya’s role as the gateway to Europe, and the last place before migrants make the treacherous, often deadly, trip across the Mediterranean Sea, has rendered the country a strategic target for efforts by the European Union and Italy bilaterally for agreements aimed at reducing the number of people making this last stretch of their journey.

The general aim of these agreements have been effective, reducing the number of migrants who successfully cross the Mediterranean, as well as the number who die in transit. But how has this feat been accomplished?

The main holding facility at the Sikka Road detention facility operated by the Libyan Ministry of Interior in Tripoli. About 1400 migrants, mostly from Sub-Saharan Africa, are detained in deplorable conditions as they await repatriation to their countries of origin.

Detention Centers like the one pictured above effectively quarantine and imprison migrants who are caught making the journey. Numerous agreements made by the EU and Italy, with Libya’s GNA as well as with militias, have funded the construction and management of these detention centers. What follows is a profile of these detention centers, including how they are funded, who is running them, reports by international organizations who have conducted limited oversight, and the experiences of the migrants being detained.

Fast Migrant Facts

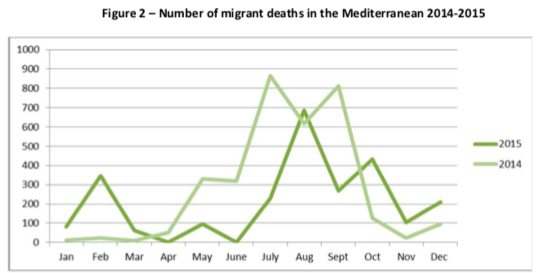

While smuggling, due to its illicit nature, may not be recorded easily, various groups have attempted to put numbers to the phenomenon.

Source: European Parliament Briefing on Combatting Migrant Smuggling into the EU (April 2016)

In late 2017, international organizations estimated that upwards of 400,000 migrants were present in Libya, around 45,000 were registered as refugees by UNHCR. While the numbers of irregular migrants arriving to Libya remains consistent, the number embarking to Italy has dropped since highpoints in 2014 and 2015. While in 2016, 180,000 migrants embarked to Italy through Libya, only 120,000 did in 2017, and by mid-2018, only 20,000 migrants had completed the journey.

Source: European Parliament Briefing on Combatting Migrant Smuggling into the EU (April 2016)

Italy and the EU

Bilateral agreements between Italy and Libya have a long history. 2008 was the year the two countries ratified the Italy and Libya “Friendship Pact,” in which Italy agreed to provide Libya with 5 billion dollars of infrastructure funding over a 25 year period as compensation for the abuses of colonization. The Friendship Pact did not come without strings – in exchange for the funding, Libya agreed to intensify its counterterrorism tactics and work with Italy to combat organized crime, drug trafficking and illegal immigration. The Friendship Pact was jointly paid for by Italy and the EU.

In the ten years that have passed since then, agreements made with Libya by the EU and Italy follow much in the footsteps of the original Friendship Pact, focusing on boosting Libya’s capabilities to fight organized crime and illegal immigration (including irregular migration). In 2017, Italy again sought a comprehensive agreement with the Libyan government that could match the breadth of the Friendship Pact, however, the various branches of the Libyan government, acting inharmoniously, have not jointly approved the agreement. The biggest contention with the agreement pointed out by the Libyan parliament and courts – that it provides support for Libya to continue to host large numbers of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants.

As the EU and the Italian government continue to send funding to Libya in support of their goals, actors critiquing these actions have ranged from the Global Legal Action Network to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). A 2018 report by the Global Detention Project describes the Global Legal Action Network’s lawsuit filed against Italy at the European Court of Human Rights over a situation in which “the Libyan coast guard interfered with an NGO search and rescue operation resulting in the deaths of at least 20 people. Survivors of the incident were “pulled back” to Libya by the Libyan coast guard where they “endured detention in inhumane conditions, beating, extortion, starvation and rape. Two of the survivors were subsequently ‘sold’ and tortured with electrocution.” The Libyan coast guard is partly funded by the EU and Italy.

In the region, the EU has taken aggressive steps to counter irregular migration before migrants even arrive at Libya. Since 2015, the EU as maintained an “EU Trust Fund for Africa” which takes a largely security-driven approach to stopping migration before it even begins in the origin states of Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal. Including both civilian and military missions, the EU Trust Fund for Africa has been referred to as an expansion of the EU’s borders south to the Sahel. It has been critiqued for doing very little to aid the core causes of migration, such as poverty, instability, and terrorism. It is overwhelmingly focused on stopping migration than with providing safe, legal entry routes for migrants and asylum seekers.

Libyan Law

For migrants who are intercepted in Libya, the law of this largely lawless land does not offer them much comfort. While Libya does have a legal framework to deal with irregular migration that predates 2011, much of the laws involved are not harmonious and leave many questions unanswered. Between the two most important laws regarding the status of irregular migrants, Law No. 6 (1987) Regulating Entry, Resident and Exit of Foreign Nationals to/from Libya and Law No. 19 (2010) on Combating Irregular Migration, what is certain is that irregular migration is criminalized and subject to both fines, imprisonment, and expulsion. Despite Libya’s previous ratification of a number of international human rights treaties, its legal framework to tackle irregular migration is does not adhere to international norms regarding the treatment of irregular migrants. This situation makes it harder for international organizations to aid irregular migrants in the country, necessitates that smugglers go to more perilous lengths to ensure the passage of migrants, and, because laws have not been updated to accommodate Libya’s fractured power structure, does not provide strong answers as to who has rightful authority over irregular migrants during their detention in the country.

The Migrants

The vast majority of migrants transiting through Libya toward Europe are adult males, though women and children are becoming more common. While traditionally most migrants came from impoverished backgrounds and were low-skilled, there has gradually been in an increase in skilled, educated adults embarking on the journey, suggesting that bleak economic prospects are fueling a large portion of the migration.

In terms of where migrants are originating, Sub-Saharan African countries source the highest number of migrants utilizing the Libyan route. These migrants endure extreme conditions as they make their way through the Sahel, usually through the main hub of Niger. Due to agreements within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Africans may move freely within West Africa to Niger. After migrants cross the Nigerian border, they are “illegal” for the first time during their journey. Thus, it is at this transit point that the use of smuggling network becomes most necessary.

Factors pushing migrants out of their countries include extreme poverty, food insecurity, authoritarian regimes, instability, and, increasingly, climate change, as reflected by the sharp increase of migrants originating in the Lake Chad region and Nigeria.

The Smuggling Networks

The organizational structure of the smuggling networks operating in this region is often referred to as the ‘enterprise model,’ in which large numbers of autonomous smaller, flexible criminal groups or individuals organize with one another only when profitable. Smuggling groups profit off of migrants by charging smuggling fees. These smuggling fees, however, are not a ‘one size fits all’ venture; there are packages and services targeted to fit the migrants’ budget and desire for comfort and safety during the transit.

Libya’s particular circumstances has seen smuggling networks become uniquely involved with Libyan militias, sometimes operating as part of the official government, who organize agreements for the transfer of migrants directly from the hands of the smuggling group to the detention centers.

Illegal immigrants from Nigeria and South Niger flee their hunger stricken homelands and cross the Libyan border on trucks, in the hope of finding work. The truck drivers often abandon them in the desert, 200-250 kms from the cities, if they see any sign of control. The migrants are used to living in forests and are completely unprepared for the desert.

Detention Center Operators

Officially, under Libyan law, detention centers fall under the administration of the Libyan Directorate for Combating Illegal Immigration (DCIM), with the Ministries of the Interior and Defense also serving important functions in the detention of migrants. Between 2011 and 2014, militia groups active during the civil war were absorbed to create the new Ministries of the Interior and Defense. The result has been Libya’s conversion into a patchwork state, in which the militias have maintained much of their own internal power structures and have not been fully absorbed into the state. Thus, while some detention centers are operating under the official administration of DCIM, others are operating sans government oversight under the administration of these militias, and still others are operating out of reach of both the DCIM and the government-affiliated militias. Thus, the exact number of detention centers active in Libya, as well as each of their administrators on the ground, is unknown. As described by the Global Detention Project, the situation is such as that “sometimes facilities are run by individuals officially on the payrolls of the DCIM, but who actually work on behalf of, or are members of, militias. In other cases, centres that the DCIM considered closed may actually be in use by non-state actors. Militias have also proved themselves adept at navigating relations with Libyan institutions as well as international actors including the Italian government and the EU.” Amnesty International has preferred to call the “unofficial detention centers” run by militias and other groups in undetermined locations “places of captivity,” estimating that thousands of migrants are being detained at these locations.

Here we begin to answer the question of how administrators of these detention centers profit. Administrators may be paid by DCIM, militias, or indirectly via EU or Italian programs jointly at any given time. However, the extent of corruption in detention centers goes beyond even these channels. The system of coercion and exploitation faced by migrants who pass through the centers includes prison guards, DCIM officials, smugglers and traffickers, corrupt coast guard officials, and the private citizens who may report them for profit (usually in this case it is private citizens who ‘hire’ migrants for labor and then report them before giving payment). The Global Detention Project reports a situation in which “sometimes DCIM centers release migrants in order to refer them to smuggling/trafficking networks with whom they cooperate, and in some cases smugglers negotiates the release of immigration detainees purely so they can force them to pay for a sea crossing to Italy.” The overall effect of this situation is that migrants are at a high risk of being extorted multiple times before gaining their freedom, in many cases, this freedom comes at the cost of paying for their own deportation.

Works Cited

Dettmer, J. (2015, September 08). Migration Crisis Aids Organized Crime. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/europe-migration-crisis-a-boon-for-organized-crime/2952482.html

Libya Immigration Detention. (2018, August). Retrieved from https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/africa/libya

Migration Through the Mediterranean: Mapping the EU Response. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ecfr.eu/specials/mapping_migration

Remac, M., & Malmersjo, G. (2016, April). Combatting Migrant Smuggling into the EU(European Union, European Parliament). Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/581391/EPRS_BRI(2016)581391_EN.pdf

European Union Center of North Carolina, Transnational Crime/Immigrant. (2016). The EU, Transnational Crime and Illegal Immigration[Press release]. Europe.unc.edu. Retrieved from https://europe.unc.edu/files/2016/11/Brief_EU_Transnational_Crime_Illegal_Immigration_2013.pdf

Rabat Process – Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development, Thematic Meeting on Trafficking in Human Beings and Migrant Smuggling. (2015, December 4). Trafficking in Persons and Migrant Smuggling[Press release]. Rabatprocess.org. Retrieved from https://www.rabat-process.org/images/RabatProcess/Documents/information-document-thematic-meeting-porto-december-2015-trafficking-smuggling-rabat-process.pdf