Author: Jessica Viola

HLTH 641: Health Communication, Spring 2021

(C (Counseling Staff, 2018)

(Counseling Staff, 2018)

Diversity and Inclusion are two buzz words in corporate America right now. I have been fortunate enough to work for large companies throughout my career, which has afforded me opportunities to educate myself and become a true advocate for diversity, equality, equity, and inclusion. There are many layers of diversity and equity in healthcare, but I am going to focus on only one. In 2019 I became pregnant and had a full-term pregnancy at 37 weeks and 2 days, to a healthy baby boy. Throughout my pregnancy, I did a lot of reading and internet searches to gain as much knowledge as I possibly could to not only stay healthy during pregnancy but learn how to advocate for myself and what to expect from my healthcare providers. This experience brought a rude awakening to the inequities that exist in the US healthcare system with pregnancy care. Some of the statistics on mortality rates and health complications for black women and infants during and after pregnancy in the United States are among the worse for developed countries.

Let’s Look at the Facts

Healthcare disparities are preventable when looking at pregnancies. With access to education and prenatal care, there would be a direct decline in maternal and infant death rates. It is important to look at historical and cultural information to assess social status, occupations, education levels, and access to healthcare when evaluating prenatal and postnatal care in the United States (Arcaya et al., 2015). On average black women are paid 63 cents per dollar to every dollar a white man makes. The US average salary for black women is $36,227 per year, which causes limited access to healthcare (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2018).

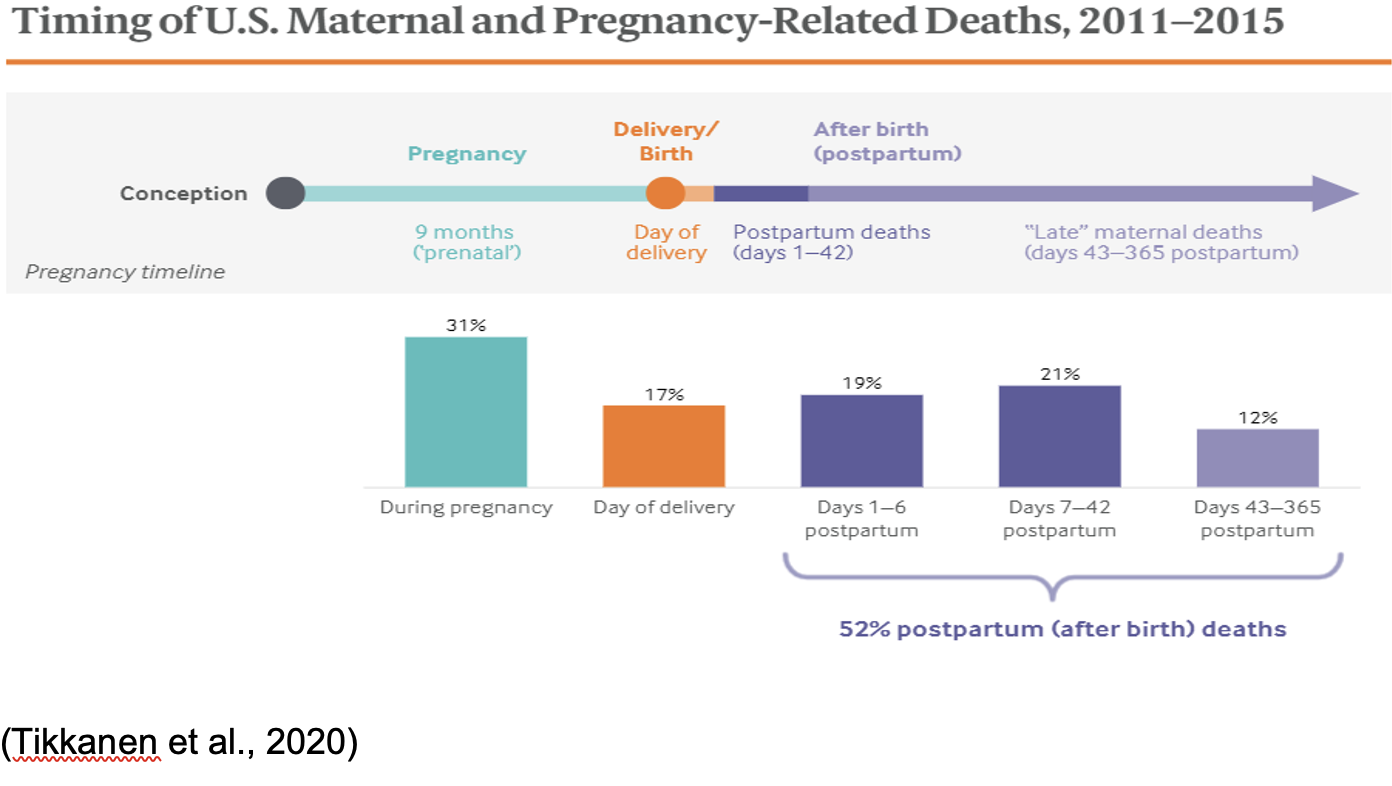

As a global leader with excess resources, the United States ranks among the lowest in regards to maternal mortality rates, with 17 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Countries such as the Netherlands, Norway, and New Zealand have three or fewer per 100,000 live births (Tikkanen et al., 2020). More than half of maternal deaths occur postpartum:

Digging in deeper to the above statistics, for black women this rate is 37.1 per 100,000 live births This is more than double the average rate.

In addition, although infant mortality rates continue to decline, black infants are twice as likely to die within the first year of life than white infants (Alio et al., 2009). Statistics like these are unacceptable and trying to understand the reasoning of disparities between races is baffling.

According to a 2014 study, ob-gyns are predominately females, representing 61.9% of the ob-gyn population. Also, ob-gyns had the highest diversity ratio of the studied physicians. When looking at the total physician workforce, 74.4% are white (Rayburn, 2016). For 2018 total physician race and ethnicity percentages click here: AAMC Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. Continued research needs to be conducted to uncover if there is a causal effect of care provided by a doctor of a different race than that of your own to determine if care is compromised.

What is the difference?

Health, age, an uncontrollable, socio-economic status?

I won’t go into all the gory details, but my labor progressed quickly and I missed the window of opportunity to receive any pain medications or an epidural. The delivery of my son was an uneventful vaginal birth. However, the afterbirth (the placenta) did not come and the obstetrician had to manually extract it. There are risks with this, the first one is ensuring the whole placenta is removed and there are not pieces floating around in the uterus. If placental tissue is not completely removed, it can lead to a hemorrhage or infection. In extreme cases, a hysterectomy may need to be performed. Retained placentas occur in one to three percent of vaginal deliveries and are a common cause of maternal morbidity (Perlman & Carusi, 2019). The outcome could have been different, but I believe my doctor saved my life and followed up with all necessary procedures to ensure that the placenta was fully removed (internal ultrasound). Fast-forward six weeks postpartum, I had an episode in the middle of the night where I fainted three times. I did not go to the hospital immediately, but then the next morning decided to go, knowing the risk factors of a potential blood clot. Women are at an increased risk of developing a life-threatening blood clot for up to three months postpartum (CDC, 2018). Know your risks: Learn about Blood Clots | CDC. With my own experience, I cannot help but advocate for all women to receive the proper medical treatment and attention. In my case, it was my first pregnancy and an unknown.

Between 2005-2014 there were 40,922,512 live births and 7,031 maternal deaths in the US. The mortality ratio during this time frame was 15.6% for every 100,000 births. Of the data collected, there was an increase in mortality among black women. Also, there was a significant correlation to gestational diabetes, c-section deliveries, unplanned births, and four or fewer prenatal visits with an increase in mortality (Moaddab et al., 2018).

Cardiovascular-related pregnancy mortality rates are declining; however, other cardiovascular diseases and cardiomyopathy rates are increasing. There is not enough research explaining why cardiomyopathy rates are increasing among pregnant women, but “black women disproportionately experience higher pregnancy-related cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared with white women.” (Njoroge & Parikh, 2020). Continued research needs to be conducted to provide more insight as to why black women are at a higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease during pregnancy. Possible biological risk factors, age (being younger than 18 with multiple pregnancies or older than 30), education, income level and access to health coverage play a large role in the disparities seen in pregnancy outcomes in the US (Clay et al., 2019). It is important to note, that it is possible to be pregnant and deliver a baby in the US without having any healthcare coverage.

Black women are more likely to develop other conditions associated with pregnancy complications as well; increasing the risk associated with pregnancy at any age. These complications included fibroids, earlier signs of preeclampsia, and experiencing physical weathering (early health decline) (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2018). Black women tend to give birth at hospitals that predominantly serve black populations and these hospitals have higher rates of maternal complications compared to other hospitals (National Partnership for Women & Families, 2018).

One of the limitations on this topic is the available data, which right now seems to be from 2016 or prior. Looking at racial disparities on a national level shows government intervention needs to happen to create better education opportunities and access to healthcare. However, I did not find direct links to institutional racism tied to pregnancy outcomes.

Prevention

The statistics are known, like black women experiencing preeclampsia earlier in pregnancy or an increase in cardiovascular complications. If these are known, there is no reason they cannot be assessed, treated, or managed. The healthcare system needs to update its practices to adapt to racial/cultural needs. Each community has different needs and each pregnancy is not the same. The healthcare community treats each pregnancy the same (unless given a reason not to through prenatal visits).

One story from Harvard discusses issues of possible racism amongst the medical field, read it here: Racism and discrimination in health care. If racism exists from a professional level with doctors, then medical schools have to change their curriculum to include diversity, inclusion, and sensitivity training. Healthcare professionals are supposed to be there to care for humans and ensure their well-being. If this is not the case, what are the consequences to those not acting ethically within the field?

We need to provide access to not only education but access to healthcare for everyone. This may look like recording phone numbers for people that purchase contraceptives as well as pregnancy tests and having the health department of each county follow up. This may feel like an invasion of privacy; however, we are doing contact tracing right now for the pandemic. If this could be one small step to providing early prenatal care that can positively affect pregnancy outcomes, why would we hesitate? Learn more about the disparities and donate to the cause here: Black Women’s Maternal Health.

Policy Changes

Lastly, how do we have a conversation about maternal deaths without addressing government issues? Maternity leave is a glaring issue when looking at the United States. However, before even discussing maternity leave, what about lost wages during prenatal appointments? Salaries need to be looked at, there should be no gender pay gap. All pregnant women should be supported by employers to have appointments to ensure their health. If your employee is not healthy, the work will not be done anyway. Also, the government needs to do a better job ensuring that people understand how to access and use their benefits of the Affordable Care Act. US maternity leave is under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) that was established in 1993. FMLA provides certain employees up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave, which protects their job and any healthcare benefits provided by the company (US Department of Labor, 2021). Here is the fact sheet provided by the US government: FMLA Fact Sheet. The policies in place do not treat each person equally and does not take into account disparities, such as socioeconomic or relationship status to ensure all pregnant women have the resources to have not only a health pregnancy, but also a healthy delivery and postpartum journey. To recap, the US federal government only has a policy that provides unpaid leave. It is up to 12 weeks, at the discretion of a potentially biased person(s), and only available to certain employees. This is beyond inhumane and applies directly to me. I want to start a charity lobbying for policy changes.

In January 2019 I was laid off from a company that I was with for almost seven years. I continued to receive severance pay through August of 2019. I started with my current employer in June 2019, the baby came early. I was only with my employer for 19 weeks by the time he arrived. To qualify for employer maternity benefits, which was up to 16 weeks leave, I had to be employed by them for 26 weeks. Living in NYS provided some coverage, but since I wasn’t with my current employer for 26 weeks, I hadn’t paid into the system long enough. Again, I was receiving and paying into the system through my severance, but NYS does not look at past employment for qualification. I was entitled to six weeks, below my cost-of-living state-paid benefits. My benefits were extended due to some postpartum issues. Being married provided a privilege of being able to figure it out financially. Six weeks is not long enough. Not everyone can make those adjustments. Preventable added stressors should not be a concern. Stress causes major health consequences. The US claims to support families and wants new births, but their actions (inactions) clearly state they do not.

*Additional Resource: CDC Hear Her Campaign: CDC Resources

Keywords: pregnancy, mortality rates, health coverage, inequity, disparity, retained placenta, maternity leave

References

AAMC. (2018). Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018

Alio, A.P., Richman, A.R., Clayton, H.B., Jeffers, D.F., Wathington, D.J. and Salihu, H.M. (2009). An ecological approach to understanding black-white disparities in perinatal mortality. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0495-9

Arcaya, M.C., Arcaya, A.L. and Subramanian, S.V. (2015). Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Global Health Action, 8(1). doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27106

Counseling Staff. (2018). [Pregnancy-related mortality rates] [Photograph]. Northwestern: The Family Institute. https://counseling.northwestern.edu/blog/mental-health-counseling-black-women-pregnancy/

Clay, S.L., Griffin, M. and Averhart, W. (2019). Black/white disparities in pregnant women in the United States: An examination of risk factors associated with black/white racial identity. Health and Social Care in the community, 26(5). doi: 10.1111/hsc.12565

Expecting or recently had a baby? (2018). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: Expecting or Recently had a Baby? Learn about Blood Clots | CDC

Institute for Urban Policy Research & Analysis. (2018) [Disparate rates of black women dying: At birth and postpartum period] [Photograph]. The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved from https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/iupra/news/new-policy-brief-on-maternal-health-disparities-for-black-women

Moaddab, A., Dildy, G.A., Brown, H.L. Bateni, Z., Belfort, M., Sangi-Haghpeykar, H. and Clark, S. (2018). Health care disparity and pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005-2014. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(4). doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002534

National Partnership for Women & Families. (2018). Black women’s health maternal health: A multifaceted approach to addressing persistent and dire health disparities. National Partnership. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/health/reports/black-womens-maternal-health.html

Njoroge, J.N. and Parikh, N.I. (2020). Understanding health disparities in cardiovascular diseases in pregnancy among black women: Prevalence, preventive care, and peripartum support networks. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports, 14(8). doi: 10.1007/s12170-020-00641-9

Perlman, N.C. and Carusi, D.A. (2019). Retained placenta after vaginal delivery: Risk factors and management. International Journal of Women’s Health, 11. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S218933

Rayburn, W.F., Xierali, I.M., Castillo-Page, L. and Nivet, M.A. (2016). Racial and ethnic differences between obstetrician-gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(1). doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001184

Tello, M. (2020). Racism and discrimination in health care: Providers and patients. Harvard Health Publishing Harvard Medical School. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/racism-discrimination-health-care-providers-patients-2017011611015

Tikkanen, R., Gunja, M.Z., FitzGerald, M. and Zephyrin, L. (2020). Maternal mortality and maternity care in the United States compared to 10 other developed countries. The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries

Tikkanen, R., Gunja, M.Z., FitzGerald, M. and Zephyrin, L. (2020). [Timeline of pregnancy related death rates] [Photograph]. The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2021). Addressing health inequities among pregnant women. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/resources/news-media/addressing-health-inequities.html

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2021). Expecting or recently had a baby? Learn about blood clots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/infographics/blood-clot-pregnancy-info.html

U.S. Department of Labor. (2021). Family and Medical Leave (FMLA). Retrieved from: https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/benefits-leave/fmla