Conclusion

Pollaiuolo’s Tomb of Sixtus IV (figure 69) served many purposes, expanded the iconography of the Liberal Arts, and, as Jill Blondin wrote, “serve[d] as permanent reminders of the pope’s erudition.”[150] Thus, this funerary monument further developed Sixtus’s association with the expansion and patronage of the Liberal Arts, establishing him as an intellectual achieving divine wisdom. However, Pollaiuolo departed from the traditional descriptions of the disciplines, instead incorporating aspects of the Renaissance Humanist tradition. By bridging the gap between Medieval Scholasticism and Renaissance Humanism, Pollaiuolo’s images of the Liberal Arts further developed the potential concord between Platonic and Aristotelian thought via textual inscriptions. Through the overall layout of the tomb, Pollaiuolo established varying hierarchies through the inclusion of della Rovere oak branches and semi-nudity to communicate the interaction and importance of each discipline. Situating himself as an artist capable of illustrating these complex intellectual concepts, Pollaiuolo further demonstrated the rise of visual art as an intellectual discipline through his synthesis of classical texts and adaptations within each panel. Later commissioned to create the tomb of Pope Innocent VIII (figure 70), Pollaiuolo reverted to the earlier wall tomb style, including an effigy of the pope surrounded by allegorical figures of the Virtues. Although not as innovative as his earlier tomb, it reflects Pollaiuolo’s success in creating Sixtus’s tomb as he was commissioned for another papal tomb.

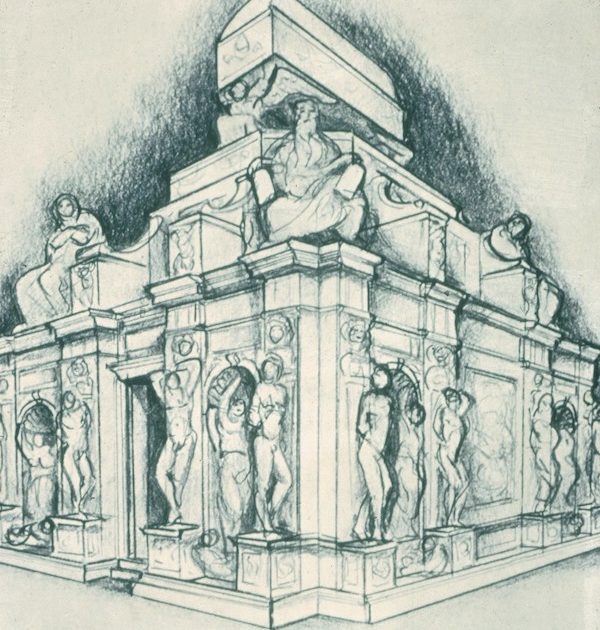

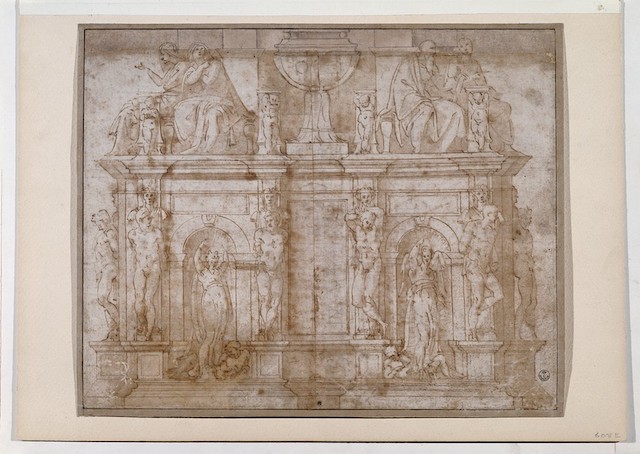

Later tombs rarely included any other representation of the Liberal Arts with the exception of Michelangelo’s designs for the tomb of Julius II (figures 71-73). Although uncompleted, the designs indicate a desire to surpass the complex hierarchy established between the Liberal Arts, Virtues, and the Effigy displayed on Sixtus’s tomb. Via a grander scale, complex design with allegorical figures, and devotion to the Virgin, the designs for Julius’s tomb reflect this desire to exceed Sixtus’s tomb in complexity and scale. Further, scholars have established Julius’s tomb as a Neo-Platonic and Augustinian allegory of the triumph of the soul over death and time, throughout the three levels.[151] Mary Garrard examines the connections between Julius II and Sixtus’s tomb extensively, arguing that in the drawings for Julius’s tomb, at least ten to fourteen figures were intended to represent the Liberal Arts.[152] The second tier’s winged victories, with incomplete hands, were likely intended to hold items related to their discipline. She argues Michelangelo likely included the traditional seven disciplines, with the additional the three of Theology, Philosophy and Prospectiva, as well as Poetry, and three plastic arts:, Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. She argues Michelangelo likely included the traditional seven disciplines, plus the three of Theology, Philosophy, and Prospectiva, as well as Poetry, and three plastic arts, Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture.[153]

Further, as Julius was involved in the design of both tombs, until his death in 1513, it is likely that he incorporated similar elements in both tombs, developing the themes successfully established in Sixtus’s to his own.[154] Initially designed to be placed in the center apse of St. Peter’s following his redesign of the basilica, Julius’s tomb would have been placed similar to his Sixtus’s tomb in the center of the Cappella del Coro that Sixtus built. Additionally with the inclusion of Moses and the figure of St Paul, further association to the della Rovere family would have been established, building on the della Rovere heraldic oak branch, papal keys and Giuliano’s insignias throughout Sixtus’s tomb. Finally, the initial drawing indicates that the effigy of the pope was to be raised by angels towards the Virgin and Child, demonstrating the dedication of Julius to the Virgin Mary, a theme established throughout Sixtus’s papacy, the Cappella del Coro, and the Tomb of Sixtus IV.

However, despite aspirations for a tomb that surpassed Sixtus IV’s tomb, Julius II’s tomb was ultimately unfinished. The final project had far less grandeur and complexity compared to Sixtus’s elaborate allegorical tomb. Thus, unparalleled in its unique representations of the Liberal Arts, Pollaiuolo’s Tomb of Sixtus IV, serves to visually demonstrate the development of Humanist thought and the advancement of the Liberal Arts throughout the Italian Renaissance. The inclusion of new disciplines and textual inscriptions bridged the gap between Humanistic and Scholastic traditions, and sought to establish further dialogue between Aristotelian and Neoplatonic thought.