History of Papal Tombs and Depictions of the Liberal Arts:

The Tomb of Sixtus departed from earlier, more conventional papal wall tombs. Many other popes utilized wall tombs, with full sculptural figures in alcoves along the wall, and the sarcophagus in the center. The only other free-standing papal slab tomb before Sixtus IV’s was that of Martin V (figure 10).[47] This reminds us of Martin V’s role in moving the papacy back to Rome from its previous seat in Avignon. As Julian Gardner noted, free-standing, slab tombs were much more common in Avignon and in the North.[48] Thus, in selecting a slab tomb, as patron of Sixtus’s tomb, Giuliano della Rovere likely referenced his own time serving the papacy in Avignon. Further, the tomb style alludes to Sixtus’s expansion and restoration of Rome by visually connecting his tomb to Martin V, a pope who increased the strength and power of the papacy by returning it to Rome.

Having investigated the intellectual circle around Pope Sixtus IV, it should be acknowledged that this tomb was commissioned by one of the closest members of his circle: Giuliano della Rovere, the nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, who would later become Pope Julius II. Under Sixtus IV from 1480-1481, Giuliano was sent to Avignon as well as other regions within France and Burgundy on a diplomatic mission.[49] Thus, as many of the tombs within Avignon were free-standing slab tombs, the influence of Giuliano’s time in Avignon can be found on the overall design of the tomb. As Gardner writes, there was a revival of the freestanding tomb in France that was thereby translated into Italy with Sixtus’s tomb.[50] It is likely that by choosing a floor tomb, Giuliano illustrated his time serving the papacy in Avignon. Although Giuliano/Julius II’s own tomb, which would have been

designed by Michelangelo beginning in 1505, varied in the overarching thematic program, he retained the expansive floor tomb, and as Mary Garrard argues, even included references to the Liberal Arts.[51] As Jill Blondin examines, it is likely that Giuliano della Rovere understood the impact that Sixtus’s tomb had on demonstrating Sixtus’s erudition and power through memorialization, explaining:

“Funerary monuments explicitly demonstrated dynastic power and Sixtus was the first member of the della Rovere family to recognize the usefulness of tombs for conveying these ambitions. The classicizing funerary monument, which became a symbol of status during Sixtus’s reign, certainly taught Giuliano della Rovere, the future Julius II, about the tomb as the perfect vehicle for expressing eternal authority.”[52]

Thus, through his contributions to his uncles’ tomb design, Giuliano developed an understanding of how tombs could be further used to memorialize an individual, demonstrating their learning and accomplishments. Moreover, Giuliano’s influence can be found on the tomb with the inclusion of vanguard scholars, incorporating both Aristotelian and Platonic thought through the notion of harmony and the interaction between the various disciplines. Therefore, this tomb represents both Giuliano and Sixtus as it reflects the Humanist, vanguard scholarship that grew under Giuliano and Sixtus, while Sixtus’s erudition and education as a Scholastic is displayed reflecting his mastery of each discipline, further establishing Sixtus as a bridge between Scholastic and Humanist scholarship. The tomb serves to merge these two periods and methods of thought into one monument, reflecting the contemporary shift in thinking.

Additionally, one of the highly influential projects completed by Sixtus IV was the expansion and opening of the Papal Library to the Papal Curia and professors at the University of Rome.[53] Continuing the work begun by Nicholas V, Sixtus IV oversaw the expansion of the project. Further, as Lee explains in his book on the circle of Sixtus IV, “like Martin V and Nicholas V, [Sixtus IV] intended to make Rome into the first city in Europe, the caput orbis, which owed its existence and its splendor exclusively to the papacy.”[54] In visually connecting the tomb of Sixtus to that of Martin V, Giuliano further ensured that Sixtus’s legacy would be connected with Martin V, a pope who expanded the power of the papacy and enhanced the city of Rome.

Further, the only other previous tomb that included representations of the Liberal Arts was the Tomb of Robert of Anjou, or Robert the wise, in Naples, constructed by Paccio and Giovanni Bertini (1343-45). A wall tomb with an extensive iconographical program, the Liberal are shown directly below the pontiff’s effigy.[55] As papal tombs traditionally included Christian iconography, Pollaiuolo, by including pagan iconography in the disciplines of the liberal arts “departed from recognized visual conventions and established new ones” allowing the tomb to serve as a vehicle for iconographic development in the Liberal Arts.[56] Other sculptural reliefs of the Liberal Arts are found in the pulpits in Pisa and Siena, which depict the seven traditional disciplines underneath the narrative biblical imagery. By including figures of the Liberal Arts on pulpits, laypeople who attended sermons could visually connect the disciplines with theological teachings. Thus, reflecting the interconnected nature of the Liberal Arts and the Catholic doctrine. Together with those on the Campanile of the Duomo of Florence, all retain the medieval convention of depicting the Liberal Arts as enthroned figures, indicating their integration into the Catholic Church.[57] However, by selecting the Liberal Arts for the tomb imagery, the inclusion of each discipline rendered the tomb as a visual record of the intellect of the individual entombed below.

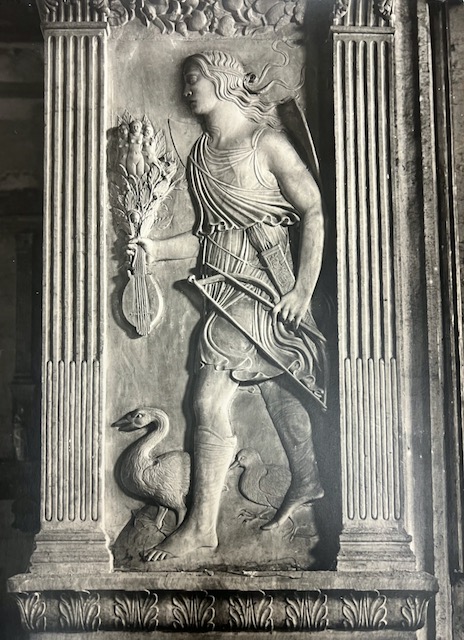

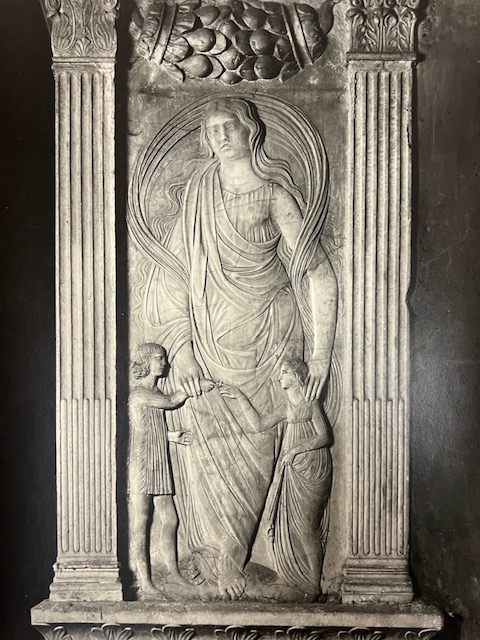

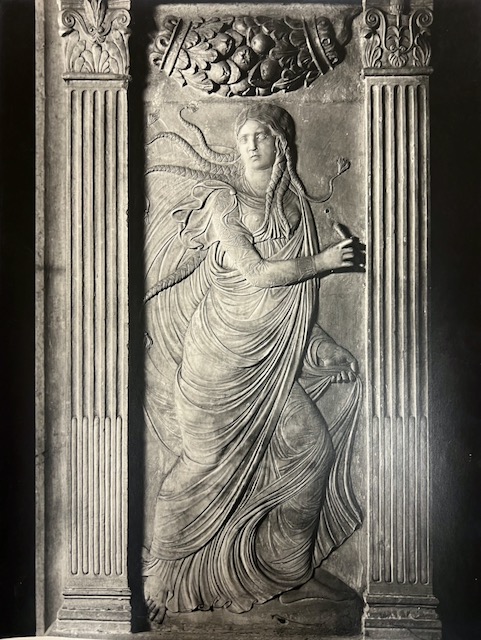

The only other expansive sculptural cycle that displays the allegorical figures of the Liberal Arts is Agostino di Duccio’s cycle within the Temple Malatestiano in Rimini (1449-1457) (Figures 11-16).[58] Within the church, sculptural cycles within side chapels depict the Sibyls, Tombs of the Ancestors, Apollo and the Muses, and a Chapel of the Planets. On the pilasters leading into a side chapel dedicated to the Liberal Arts are low relief panels depicting each discipline. They serve as transitional representations of the Liberal Arts between earlier, enthroned figures, and the reclining nudes of Pollaiuolo’s tomb because while they are not semi-nude their naturalistic female bodies are more animated.[59] Each figure is carved in much lower relief, and is less identifiable than those on Sixtus’s tomb, as no inscriptions inscribe their respective disciplines. For example, the figure of Rhetoric is shown standing with her mouth open and an intricately carved breastplate under her robes. Described by Capella, Rhetoric is depicted with a helmet and arms, although this is translated into an ornate and decorative breastplate. However, the figures similarly adhere to the iconographic descriptions as detailed by Martianus Capella, Boethius, and Alain de Lille.

Figures 11-16. Agostino di Duccio, Details of Philosophy, Dialectic, Rhetoric, Music, Poetry, Mathematics, Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini, c.1449-56

Sixtus’s tomb combined the form of Martin V’s floor tomb with the function of Robert of Anjou’s and other papal tombs to clearly establish Sixtus as a scholar. Yet by situating the tomb within the visual program of the Cappella del Coro, Pollaiuolo’s iconographical innovations and relationships established within each discipline were an inventive method to display the pope’s lasting influence on the traditional disciplines of the Liberal Arts. As the images of the Liberal Arts invented by Pollaiuolo on the tomb of Sixtus IV are highly complex and deviate in key respects from their precedents, this capstone will focus on the innovations in these panels: relating them to their source texts and detailing Pollaiuolo’s inventions throughout the tomb. The following sections will investigate these Liberal Arts in more detail.