Astrology

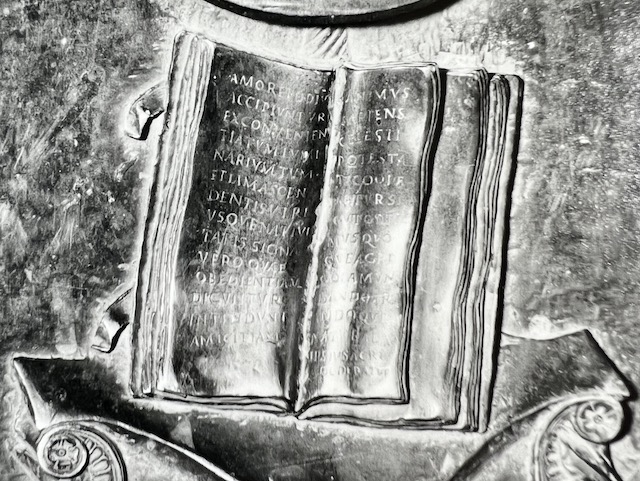

Holding a sphere and looking up to the heavens, the figure of Astrology (figure 35) is shown sitting at an ornate desk. She occupies the central left panel, the last of the arts of the Quadrivium. To her left and right are open books and in the top right corner of her panel are nine parallel bars, representing the nine spheres of the universe. To her left on the desk, the book reads “whoever has aptitude in anything will certainly have a powerful star indicating this under his birth sign. A soul able to discern things will follow the truth better than he who strives for the summit in science.”[95] (figure 36) This quote thus presents astrology as influential in determining the birth signs of learned men. It provides a reason beyond learning to account for wisdom, further associating the Liberal Arts with divine wisdom. The book on the right has another quote, making the inscriptions within the panel of Astrology the longest in the tomb (figure 37). It reads “love and hate are explained from the constellation of the stars or from the sign ascendant at birth. Signs which command obedience, direct towards friendship. A wise soul will co-operate with heavenly power just as the best peasant clearing and plowing will co-operate with nature.”[96] Again, this supposes that individuals were on a predetermined path, given at birth, yet relates it to the question of how to contemplate the divine, if an individual has an active or passive role in their life. Ettlinger argues that both inscriptions are verbatim from Ptolemy’s Centiloquium, translated by Georgius Trapezuntius whose patron was Sixtus IV. This translation was present within the Vatican library during the time of Sixtus; it is likely Sixtus and/or his intellectual advisors would have been familiar with this text as he vastly expanded the library’s holdings during his papacy. However, Ptolemy is not cited within either Capella or Alain de Lille. Instead, the work of Ptolemy is included and discussed both through inscription and in the surrounding panel details in the figure of Astronomy.

As the inscribed texts do not visually relate to the panel of Astrologia, we must turn to the writings describing the discipline. Although writings used Astronomy instead of Astrology, at this time the disciplines were not as distinct as they later became and so the two can be thought of as the same. Capella described Astronomy decked with gems as her brow was starlike, her hair sparkled, and she had wings in a golden hue.[97] She held a forked sextant in one hand and the other had a book showing the calculations of orbits of the planets. However, this representation of Astrology closely relates to the description found in Alain de Lille’s Anticlaudian. In it he writes that Astronomy was fixed upon the stars with a sphere in her hand.[98] Further, the earth was described as having five parallels cut into separate zones which correspond to the sphere that Astrology holds as there are five dividing lines running vertically to the sphere.

Although the last traditional discipline of the seven Liberal Arts, the fact that the figure of Astrology was often represented or described last signified her disciplinary importance.[99] This would later be changed with the inclusion of Philosophy and Theology in the general study of the Liberal Arts, but in the original seven disciplines, Astronomy or Astrology was the closest to the heavens and therefore traditionally occupied the conceptual summit. Her importance is conveyed on the tomb through her gaze upwards towards the heavens, combined with the number of inscriptions provided within the panel, and her central location on the side which will later be examined.

Figure 35. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Tomb of Pope Sixtus IV, Detail of Astrology, c. 1484-1493

Figures 36 and 37. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Tomb of Sixtus IV, Details of Astrology Inscriptions, c.1484-1493