Rhetoric

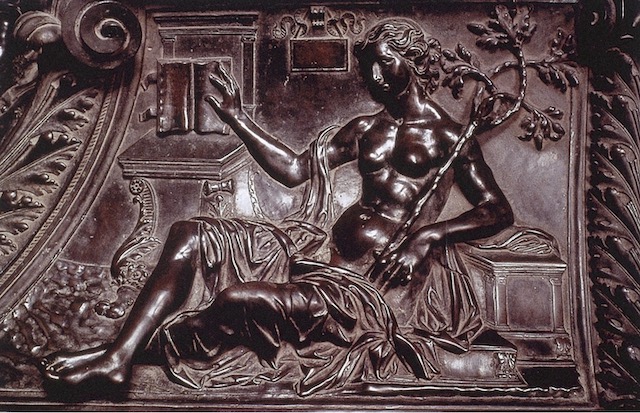

Grouped together at the bottom of the tomb, Pollaiuolo included all the traditional arts of the Trivium. Rhetoric (“Rhetorica”) on the left (figure 17) is shown in a reclining position, her legs draped with a cloth, her right arm extended to hold open a book while her left props up her torso and holds an oak branch. The symbol of the della Rovere family, the oak branch associates this discipline with the pope’s own study. She is shown bare-breasted with her garment draping over her right arm. As Ettlinger notes, her pose is that of Grammatica in reverse, based on the figure of Tellus (figure 18) on Hadrianic and Antonine coins, an example of which was documented in Sixtus’s collection.[60] Tellus was an ancient Roman fertility deity, responsible for the growth and fertilization of crops. The oak branch is made to cleverly stand-in for the vine that Tellus holds. Further, as Tellus symbolized fertility and growth of the land, it indicated the desires of Sixtus and the della Rovere family to enhance and bring prosperity to the city of Rome.

Employing this coin relief as an exemplum for his own depictions of the female body, Pollaiuolo’s confirmed his own knowledge of antiquity and appealed to his patron by referencing the object within the papal collection. Moreover, this choice communicated the pope’s connections to Ancient Rome and his desire to be commemorated as both a skilled orator and master of history and the disciplines of the Liberal Arts.[61] Rhetoric’s paired figure of Grammar does not hold a Della Rovere oak branch despite Grammar being associated with an oration in Medieval texts. While Sixtus IV was a renowned orator and sought to portray himself in such a fashion,, oratory skills were associated in the Renaissance with the discipline of Rhetoric instead of Grammar. Thus, Sixtus’s oratory skills are reflected within Rhetoric’s panel.[62]

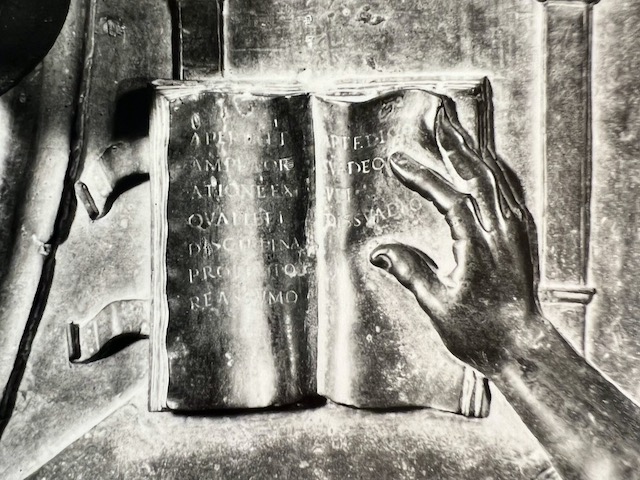

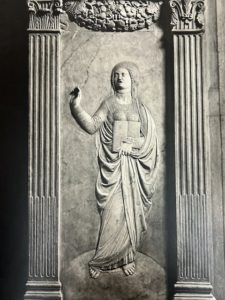

The inscription displayed in the open book (figure 19) is directed toward the viewer, as it states in the first person “with clear and strong speech according to circumstances I take to all disciplines. I speak suitably to persuade or dissuade.”[63] Ettlinger argues that this phrase paraphrases a pseudo-Ciceronian treatise, Rhetorica ad Herennium.[64]In the chapter on Rhetoric by Martianus Capella, the figure of Rhetoric, when describing her discipline to the council on Olympus, often invokes the words of pseudo-Cicero along with Virgil, Aeneid, Horace and Odes.[65] The putative importance of Cicero to the discipline of Rhetoric is shown through the multiple references within Capella’s writing, as well as in Alain de Lille’s Anticlaudian. When Rhetoric is introduced to the Greek council, she is followed by Cicero who is also present at the council. Apart from the writings of Capella and Alain de Lille, the main source texts for students of Rhetoric were primarily Cicero, Quintilian, Ovid, and Virgil.[66] Although Rhetoric is identified through her inscription and plaque, she lacks the conventional symbols of Rhetoric, specifically the traditional helmet and arms, as well as the Latin-style robe with a belt adorned with all the rarest jewels. Capella described her as a woman of the tallest stature with a helmet and arms to defend herself or wound her enemies with the robe and jeweled belt.[67] According to Capella, she also holds a scroll with a red staff, which is conventional iconography in earlier images of Rhetoric. The figure of Rhetoric depicted in Rimini (figure 20) corresponds with these textual descriptions. For example, she is shown with an ornamented dress and a breast-plate, alluding to Capella’s description. Further, she is shown in the act of oration, associated with rhetoric, as her mouth is open like she is giving a speech.

Pollaiuolo’s Rhetorica also lacks the attributes that Alain de Lille gives the figure in his writing: a trumpet and horn as she builds the chariot platform in his scene.[68] However, Pollaiuolo utilized the details of her hair in the latter text, as there is an appearance of gold and “the coil of [her hair] clothes her neck.”[69] Apart from this small detail, Pollaiuolo’s figure of Rhetorica inventively appropriated the visual source of the Tellus coin to create his entirely unique figure of Rhetoric. The only textual sources and descriptions that can be identified within the image are through the inscription on the book. As such, Rhetoric, and her reverse mirror figure of Grammar, showcase Pollaiuolo’s inventiveness and unique depictions of the disciplines. This mirroring of poses and reflection across the tomb will be further discussed once all the disciplines have been examined.

Figure 17. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Tomb of Sixtus IV, Detail of Rhetorica, c.1484-1493

Figure 18. Hadrianic and Antonine coin, Reverse with Tellus figure, c.170-190

Figure 19. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Tomb of Sixtus IV, Detail of Rhetoric Inscription, c.1484-1493

Figure 20. Agostino di Duccio, Detail of Rhetoric, Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini, c.1449-56