The della Rovere as Patrons and the Intellectual Circle of Sixtus IV

Sixtus IV (figure 8) was an expansive patron of the arts and the city of Rome. He commissioned many building projects such as the Ponte Sisto, the revitalization of Santa Maria del Popolo, the expansion of the Vatican Library, the creation of the Capitoline Museum, the rebuilding of the hospital Santo Spirito among many others.[31] Many of Sixtus’s projects displayed dedication plaques, ensuring that he was being identified and memorialized for his involvement in the projects and clearly presenting the themes of his patronage.[32] As Stephen Campbell noted, Sixtus IV was the first of many later popes to understand the importance of funerary monuments and their ability to idolatrize the individual.

“Funerary monuments provided the best opportunity for sculptors and their patrons to display their emulation of antique sculpture and architecture. But they also testify to cultural ambitions of another kind: the translation and reintegration into modern Christian culture of the heritage of pagan antiquity…”[33]

Sixtus IV well understood the power that his tomb and the surrounding chapel could hold by further reinforcing the incorporation of the Liberal Arts into both Theological and Humanist studies.

Sixtus IV, born Francesco della Rovere, a devout Franciscan, graduated from the University of Padua as a doctor of Theology and was voted into the role of pope after being a cardinal for only four years in 1471.[34] He became known for his expansive projects and circle, himself a skilled orator as he lectured throughout Northern Italy.[35] He surrounded himself with scholars like Giovanni Antonio Campo, Jacopo Gherardi, and Theodorus Gaza, all of whom were associated with his former mentor, Cardinal Bessarion, a Greek Neo-Platonist cardinal who sought refuge in Venice following the Ottoman takeover of Constantinople.[36] Upon his election to the papacy, Sixtus attempted to attract scholars to the University of Rome, the Studium Urbis and scholars such as Francesco Filelfo, Ioannes Argyropulos, Martino Filetico, Pomponius Laetus, Domizio Calderini, among others taught at the university throughout Sixtus’s time as pope.[37] While he attempted to entice Marcilio Ficino, who introduced Florence and Italy as a whole to Neo-Platonism, Ficino declined and remained in Florence under the sponsorship of his Medici patrons. Many of the “Men of Letters” wrote treatises on their disciplines, with some poets even writing poems dedicated to Sixtus IV.[38]

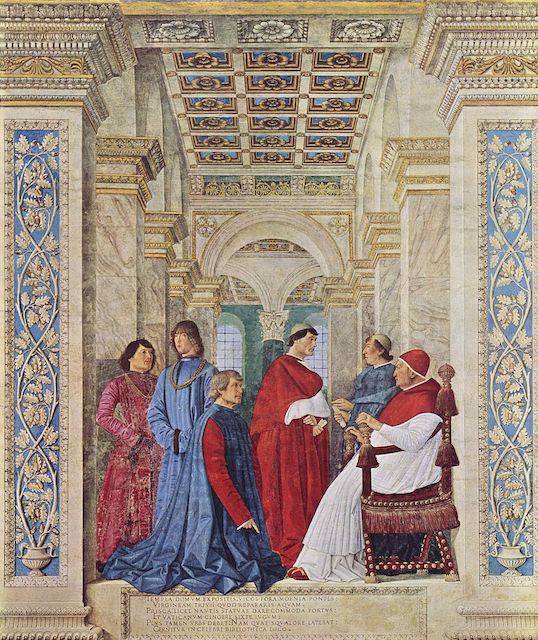

The most important figures within Sixtus’s intellectual circle were arguably Bartolommeo Sacchi, known as Platina, followed by Sigismondo de Conti. Both wrote histories of Sixtus’s life and papal rule, while Platina became the Papal Librarian in 1475 (as seen in figure 9).[39] As Lee argues in his examination of Sixtus’s intellectual circle, the Vatican Library was another facet to Sixtus’s broad patronage, and it was intended to serve “the world of scholarship in the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge.”[40] Although many in his circle were Neoplatonists, Sixtus, and later Julius’s intellectual circle wrote about the possibility for harmony and concord between the two sides of classical thought, Platonism vs Aristotelian thought. Aristotle was easier to teach as the studies were long interconnected and synthesized in Scholastic curricula, in which Francesco della Rovere was initially trained, while Plato was, as Christopher Celenza writes, “more suitable for men who are already ripe and finished scholars” and held a special appeal for humanists.[41]

This period, around Sixtus’s rise to the Papacy, experienced a shift from scholasticism to humanism that coincided with the rise of epideictic rhetoric known, according to O’Malley, as the rhetoric of praise and blame.[42] Orators of rhetoric sought to adapt classical learning to their specific point, interpreting and presenting their argument as either contrary to or in support of some aspect of Christianity, with new attention to formal eloquence.[43] This period of humanism was also related to the end of the dominance of Scholasticism, the pinnacle of which started at the turn of the 13th century with philosophers such as Bonaventure, and Aquinas.[44] While Sixtus is considered a Scholastic, at his papal court, Humanism based in epideictic rhetoric became the dominant mode of thought; and so, the balance between the two methodologies is combined within the tomb. This balance is further reflected in the choice of texts that influence each discipline’s panel.

Figure 8. Engraving of a medal of Pope Sixtus IV (1471-1484). The original medal, by an unknown artist, was made in 1481

Figure 9. Melozzo da Forlì, Pope Sixtus IV Appoints Bartolomeo Platina Prefect of the Vatican Library, 1477, fresco removed and transferred to canvas, 370 x 315 cm

Sixtus’s education was highly driven by Scholastic methods of thought. Under Sixtus, Bonaventure was canonized, suggesting the importance of the fellow Franciscan on Sixtus’s education. In Bonaventure’s writings, the most important aspect was that through scholarship, the mind could ascend to God, as demonstrated by his The Mind’s Road to God (Itinerarium mentis in Deum), as well as his outline of Theology and Reduction of the Arts to Theology (De reductions atrium ad theologiam). In his philosophy, Bonaventure was able to combine both schools of Aristotle and Plato, providing a balance between the two. Yet, scholasticism’s raison d’être was to establish the unity of truth.[45] As Panofsky writes, “where the humanistic mind demanded a maximum of ‘harmony’ (impeccable diction in writing, impeccable proportion…) the scholastic mind demanded a maximum of explicitness.”[46] Thus, scholasticism was regarded as the mastery of complete knowledge in a discipline, whereas Humanism was the study of overarching themes related between disciplines as identified and understood in classical texts. Scholastic disputations aligned one set of authorities against the other, followed by a solution and then followed by an individual critique of the arguments rejected. As such, Sixtus’s tomb can therefore be understood as a form of scholastic disputation, comparing different authorities within each discipline, and displaying the solution visually on the tomb’s panels by combining and selecting authors and various iconographic details. However, as there is no inherent critique regarding each discipline, it can also suggest the influence of Humanistic scholarship. Each Art and associated inscription served to praise the scholars of the discipline, and ultimately the pontiff as a form of epideictic rhetoric. Thus, the combination of Humanist and Scholastic scholarship throughout the tomb visually displays Sixtus’s role in bridging the gap between the two, as the rise of epideictic rhetoric grew under his court. Sixtus himself served as a transition between the two branches of scholarship, contrasting the idea that there was a sudden, and all-encompassing shift from Scholasticism to Humanism.

Sixtus’s education at the University of Padua was informed by scholastic teachings and the understanding that Theology was the key to understanding human nature and becoming close to God. Yet Sixtus’s nephew, Giuliano della Rovere supported scholars who produced vanguard scholarship, developing Humanistic texts that allowed the individual to develop moral qualities that allowed them to master each discipline and thereby attain divine wisdom. Likely, Pollaiuolo, in conjunction with a probable intellectual advisor, and Giuliano della Rovere as patron would have been familiar with the evolving nature between Humanistic and Scholastic thought, and so would visually reflect this on the tomb. Therefore, Sixtus’s tomb reflects the shifting relationships between Humanism and Scholasticism during the life and rule of Sixtus IV.