Section 2: The Victorians’ Renaissance

“This is a very important and very beautiful picture. It has both sincerity and grace, and is painted on the purest principles of Venetian art- that is to say, on the calm acceptance of the whole nature, small and great, as, in its place, deserving of a faithful rendering.”[35]

– John Ruskin in his Academy Notes on Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna, following the 1855 Royal Academy Exhibition.

Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna participated in a robust debate amongst Victorian artists, critics, historians, and philosophers about how the Italian Renaissance should be defined and how it compared to modern Britain. All parties to this debate agreed upon some fundamental premises: first, the periodization of the Renaissance, starting in the 14th century and ending in the 16th century with the 1527 Sack of Rome and advent and censorship efforts of the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent.[36] The Victorians viewed the Renaissance as a model for society, a period of chivalry, classical revival, intellectual ferment and social as well as scientific advancement. More specifically, it was associated with the flourishing of humanism, or a secular system of thought that recognized the value of human action alongside the power attributed to the divine. In the sphere of the visual arts, it was linked to the development of a form of ideal beauty that struck a balance between naturalism and idealism, and the perfection of techniques such as perspective and chiaroscuro to create a convincing illusion of three-dimensionality.[37]

While Victorian thinkers agreed upon these fundamental properties of the Renaissance, they understood its significance and its relevance to the present in differing ways, as evidenced by the writings of figures such as John Ruskin, J.A. Symonds, Walter Pater, Edward Armstrong, Emilia Dilke, Cecilia Mary Ady, and Arthur Burd, among others.[38] Broadly speaking, we can divine two distinct methods for studying the Renaissance. Some, like Symonds, approached their study of the Renaissance using historicism, constructing comprehensive written histories. Others, such as Pater, gathered their understanding based on their own subjective impressions of Renaissance works from the perspective of the present. While most of these figures viewed the Renaissance as a cultural and artistic pinnacle, others, including Ruskin, upheld the “purity” of the Middle Ages as a foil to humanist secularism. Still others claimed their own age as a Victorian Renaissance, in which intellectual ingenuity and artistic creativity could solve modern ailments like industrialism, rising unemployment, hunger, and political division.[39]

An important factor driving the resurgence of interest in Italian Renaissance art in the Victorian era was a significant expansion of the British art market, enabled by sustained economic prosperity and a rise in income rates.[40] Trade in Italian Renaissance works in particular was due in part to the widespread looting of Italian collections by French forces in the Napoleonic Wars (1796-1815); many of these spoliated works subsequently circulated in the British art market.[41] Another important factor was the tenure of Charles Lock Eastlake as Keeper at the National Gallery from 1843-55, and President from 1850-65. Under Eastlake, who traveled to Italy annually to acquire works, the National Gallery’s collection of 15th- and 16th-century Italian paintings increased substantially. Among Eastlake’s purchases were works by well-known artists, including Correggio’s Madonna of the Basket; Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne; Bellini’s Doge Leonardo Loredan; Annibale Carraccci’s Temptation of St. Anthony; and Raphael’s St. Catherine of Alexandria and An Allegory (Vision of a Knight).[42] Bequests from wealthy donors also augmented the Gallery’s collection, including a large number of Italian works given by Reverend William Holwell Carr in 1831, and Robert Vernon’s gift of 157 pictures in 1847.[43] The British Institution, a private society and arts organization, also hosted exhibits of Italian “Old Master” paintings during this period.[44]

The end of the Napoleonic Wars also enabled Britons to resume travel within Europe, re-establishing the 18th-century tradition of the Grand Tour.[45] This practice was facilitated by new travel guides such as John Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in North Italy, and Handbook for Travellers in Central Italy, published in 1842 and 1843 respectively. Charles Dickens’s 1846 book Pictures from Italy, based on his travels, provided a vivid chronicle of Rome, Venice, and Naples. Like many authors, Dickens depicted Italy as if untouched by aspects of the modern world, such as industrialization.[46] This romanticized vision of Italy was also shared by many artists, such as J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), who depicted Italian land and seascapes on multiple occasions in the 1820s and 30s. Turner visited Venice, Rome and Napes in 1819-20 and Rome again in 1828-9, where he completed a series of watercolors and sketches depicting a range of vibrant Italian scenes. Many of Turner’s pictures were exhibited in the Royal Academy’s annual exhibitions, thus spurring further interest in Italian culture.[47]

The Victorian conception of the Renaissance was not simply affected by increasing encounters with Italian artworks or images of Italy. Several texts published in this period, including the translation of Vasari’s Lives, positioned the Renaissance as a pinnacle of cultural achievement surpassing the modern day. One reason for the fascination in the Renaissance was the availability of newly translated ‘Life and Works of…’ volumes during the nineteenth century, which greatly proliferated the genius of many Italian artists.[48] Several Victorian writers modelled their own studies on such texts, like William Roscoe’s Life of Lorenzo (1795) which was published in thirteen versions between 1795 and 1883.[49] Another text that used this prototype was Anna Jameson’s 1845 text Memoirs of the Early Italian Painters, which featured biographies of prominent artists like Cimabue, Giotto, Michelangelo, and Da Vinci, and Thomas Hope’s Historical Essay on Architecture (1835), which extolled the ‘mighty genius’ of Renaissance masters, especially Michelangelo.[50]

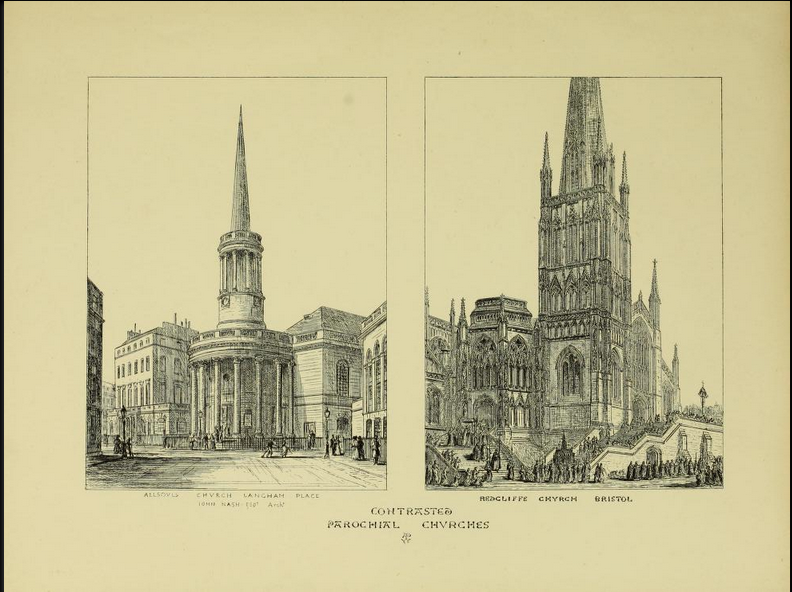

Arguably, though, two voices dominated the Victorian conversation about the Renaissance: Augustus Pugin and John Ruskin. Pugin (1812-52) was an acclaimed leading architect of the Medieval Gothic revival movement in Britain, where he sought to reform society and its taste in art and architecture through the principles of design associated with the Gothic.[51] Within his practice, he believed in creating a style that would essentially merge the experience and contributions of the past with the practicality of the present, and championed architectural principles of beauty, propriety, and truthfulness, which he felt could convey morality.[52] Pugin put Italian architecture at the center of a moral debate in his book Contrasts (1836; 2nd ed., 1842). There, he sought to demonstrate that architecture reflected the state of the society that built it. The titular “contrast” of Pugin’s book was between the beauty and spirituality of medieval Italian Gothic architecture and the corrupt soullessness of modern Victorian buildings.[53] He surveyed an array of British buildings against the foil of their fifteenth century equivalents, including the Kings Cross Battle Bridge in London (1830) and the Chichester Cross in West Sussex (1477-1503; Figure 9). Pugin appreciated the medieval period because of its supposed superiority over the Victorian age due to its Christian social order.[54] He urged his readers to connect the decay of religion in modern British society with social, political, and cultural deterioration.[55] If British architects revived the Gothic style, he believed, it would allow society to return to the solid faith and social structures of the Middle Ages, and remedy the nation’s poor taste.[56] As he wrote in Contrasts,

“It is only by communing with the spirit of past ages, as it is developed in the lives of the holy men of old, and in their wonderful monuments and works, that we can arrive at a just appreciation of the glories we have lost, or adopt the necessary means for their recovery.”[57]

By reviving the principles of Gothic architecture, Pugin argued, modern builders could regain the lost glory that he associated with the medieval past.

Figure 9. Augustus Pugin, Contrasts, Kings Cross Battle Bridge and Chichester Cross in West Sussex.

Ruskin (1819-1900) was another social reformist who believed that art and architecture embodied the conditions of the society that produced them. Like Pugin, he was opposed to the poisonous effects of industrialism and Britain, which he contrasted with what he believed to be the simplicity and harmony of Medieval society. This worldview stood at the heart of Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice, published in three volumes from 1851 to 1853. In this text, Ruskin provided a survey of Venetian architecture from the Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance eras, whose forms expressed the values of spirituality, sincerity, purity, and morality.[58] Above all, he championed Gothic architecture for its organic, functional, and harmonious appearance. [59] For Ruskin, the art and culture of Venice served as an aspirational model for England, which had been corrupted by industrial modes of production, a capitalist economy, and the abandonment of Christianity. Throughout the 1850s, he continued to publish pamphlets on the Italian masters for the Arundel Society, whose objective was to “diffuse a knowledge of the most important remains of painting” and “to elevate the standard of taste in England.”[60] In all of these texts, Ruskin upheld Italy as a standard against which modern artists should measure themselves and a model for them to emulate.

Leighton began working on Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna in 1853, the year the last installment of The Stones of Venice appeared. We know that he was inspired by Ruskin: in a letter to his mother that year, he wrote, “I long to find myself again face to face with nature, to follow it, to watch it and copy it, closely, faithfully ingenuously, as Ruskin suggests, choosing nothing and rejecting nothing.”[61] Here Leighton appears to refer to Ruskin’s 1842 book Modern Painters, in which he urged artists to devote themselves to the accurate documentation of nature, which he believed would reunite humanity with one another and with God, and would thereby resolve the degeneration of British art.[62] It is clear from Ruskin’s appreciative gloss on Leighton’s painting, cited above, that he recognized its congruence with his ideas. Ruskin went on in his Academy Notes to say that “the great secret of the Venetians was their simplicity. […] Everything in their art is done as well as it can be done.”[63] For Ruskin, then, Leighton’s painting embodied the simplicity and faithfulness to nature that he associated with Venetian painting. He also singled out for praise the accuracy of Gothic architectural elements in the painting’s background, writing that “the Church of San Miniato [is] strictly accurate in every detail … the architecture of the shrine on the wall is studied from thirteenth-century Gothic.”[64] Ruskin cited these elements to defend Leighton against critics who took issue with the painting’s composition:

“The painting before us has been objected to, because it seems broken up into bits. Precisely the same objection would hold, and in very nearly the same degree, against the best works of the Venetians. All faithful colorists’ work, in figure-painting, has a look of sharp separation between part and part.”[65]

In the passage, Ruskin defended the segmented nature of Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna, arguing that its separation made it readable for its narrative content. Ruskin argued that Leighton’s use of color actually worked to his advantage; as is clear in Ruskin’s positive comments, he felt that the painting exemplified the “purest principles of Venetian art.”[66]

Ruskin praised Pre-Raphaelite painters for the same qualities of simplicity and truth that he saw in Leighton’s art.[67] The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in 1848 by a group of students in protest against the academic conventionalism that dominated the Royal Academy. They attributed the decline of British painting to the rote emulation of the principles of the late Renaissance. Instead, they modeled their art on works before the time of Raphael, looking to the purportedly naïve, pure, and sincere qualities of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.[68] Their ultimate goal was to formulate a new way of seeing that did not rely on the traditional practice of imitation, but derived from direct observation of nature.[69] They promulgated these ideas in their publication The Germ; an essay entitled “The Purpose and Tendency of Early Italian Art” argued that

“An unprejudiced spectator of the recent progress and main direction of Art in England will have observed, as a great change in the character of productions of the modern school, a marked attempt to lead the taste of the public into a new channel by producing pure transcripts and faithful studies from nature, instead of conventionalities and feeble reminisces from the Old Masters[…]”[70]

The essay suggests that the Pre-Raphaelites were far more interested in looking to nature as the basis of their work rather than merely copying the conventions from the “Old Masters,” which they hoped would raise the artistic tastes of the modern British public.

The Pre-Raphaelites’ vision of the Renaissance is exemplified in William Holman Hunt’s 1849 painting Rienzi (Figure 10). The painting’s subject was taken from the 1835 novel Rienzi, the Last of the Roman Tribunes, by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, about the Roman papal notary Cola di Rienzi (1313-1354).[71] The painting depicts Rienzi, the future liberator of Rome, vowing to avenge his brother’s death by friendly fire with a member of the opposing Orsini family of Rome.[72] The work visualizes the moment following the death; as Rienzi’s brother lay slain on the ground, Rienzi raises his fist in an impassioned cry of vengeance. The painting reflects many notable qualities of Early Italian art, such as vibrant colors and strong usage of light and shade. As typical of the Pre-Raphaelites, the work’s emotionally fraught, suspended moment, conveys powerful storytelling techniques and expressiveness. While similar in some ways to Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna, the work operates differently in its usage of Renaissance principles. As is evident in Rienzi, the Pre-Raphaelites were interested in borrowing from the Renaissance for their emotional storytelling components. Whereas Rienzi was interested in its attention to emotional detail, Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna was Leighton’s attempt to faithfully adopt Venetian painting principles to bring Vasari’s tale to life.

Figure 10. William Holman Hunt, Rienzi, 1849, oil on canvas, 34 x 48 in, Private Collection

While Leighton and the Pre-Raphaelites emulated Renaissance art, and won equal admiration from Ruskin, not all contemporary viewers equated them. A critic writing in the Athenaeum praised Leighton’s Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna as “One of the finest pictures in the Exhibition” of 1855, “painted in the true, as distinguished from the modern, Pre-Raphaelite style.”[73] For this viewer, Leighton achieved a “true” or faithful revival of Renaissance principles as distinct from the false, “modern” pictures of the Pre-Raphaelites. This comment indicates the complexity of Victorians’ attitudes toward the Renaissance and the extent of disagreement about its essential artistic principles. For at least some viewers, including Ruskin, the painting’s purity, earnestness and simplicity had the power to transform contemporary society—a quality that surely appealed to its most famous viewers, Victoria and Albert.