preserving Community and History

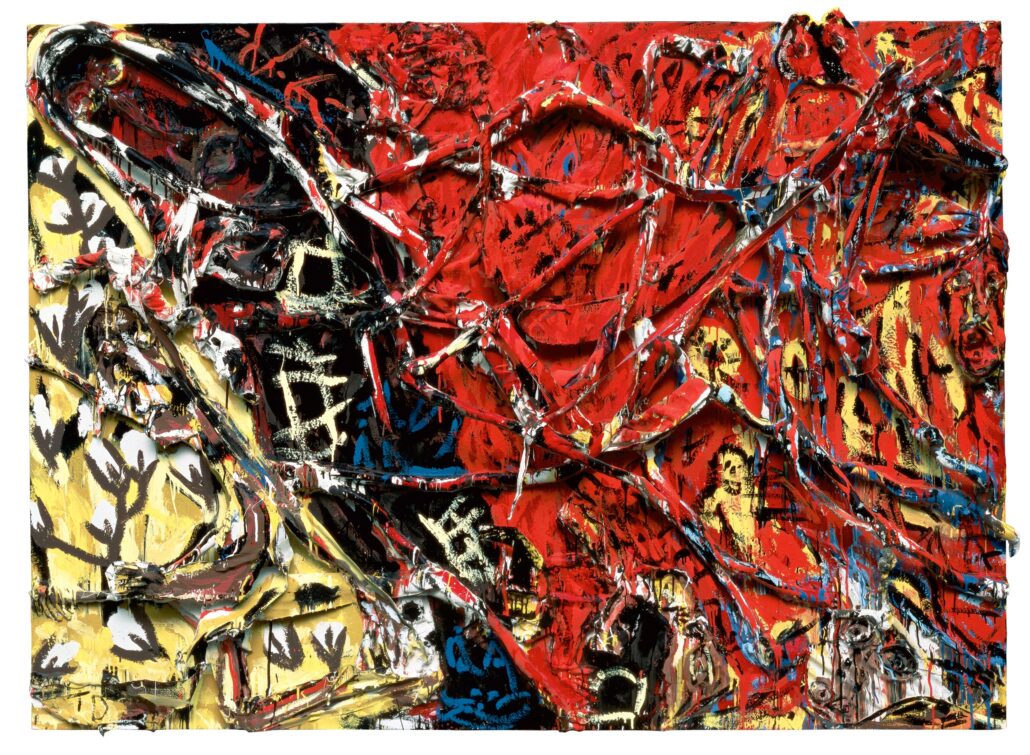

Scholars have often contextualized Dial’s experiences of surviving impoverished conditions to discuss his works, which convey a visual language about his struggles and the struggle of the Black Americans in the South at large. A significant body of scholarship about Dial and his art focuses on the oppressive realities in the South, and the literature suggests that the ensemble of discarded materials in his artworks are emblems of his survival through racial and economic hardship. When Arnett was exposed to Dial’s massive two-sided works, he felt that the material elements expressed Dial’s attention to the oppressive, discriminatory histories of Black Americans. Arnett believed that Dial’s binary construction was essential, for it “expresses the duality of American idealism and its dark failures.” This quote from Arnett specifically references American Black history and memories of slavery, the Great Migration, Jim Crowism, and Civil Rights.[56] As the work’s title indicates, History Refused to Die can engage in conversations about African American geographical displacement, cultural fragmentation, and subjugation that previous scholars have noted. Other scholars, including the American art historians and curators David C. Driskell, Joanne Cubbs, John Beardsley, Raina Lampkins-Fielder, and folklore scholar Bernard L. Herman also historicize Dial’s work by examining the aspect of Black struggle and freedom in his oeuvre.[57] Much like Arnett, these scholars argue that Dial, who was a descendant of enslaved people, developed a resourceful and expressionistic art practice that established a broader reference to oppressive Black American experiences.

Driskell and Cubbs consider Dial’s work and its connotations of Black American Southern life and culture, and they draw specific importance to his unique formal choices. In 2007, Driskell met and interviewed Dial in Bessemer, Alabama. The men conversed about how Dial’s years as an experienced, industrious worker enabled him to create his assemblages and wall art.[58] In Driskell’s essay “Giving in to the Visionary Dream: A Visit with Thornton Dial” from Hard Truths the Art of Thornton Dial, he argues that Dial’s practice with discarded objects is both an intentional artistic choice and one that evokes strategies of survival in impoverished Black communities.[59] During the interview, Driskell witnessed the compactness of Dial’s workshop, noting the various scraps of metal, twine, worn rugs, and discarded wooden crates. These materials are symbolic of Dial’s experience as a manual laborer and his technical skill in using demanding materials. Driskell asserts that Dial’s nontraditional approach using discarded objects aligns with practices of nineteenth-century Black ancestral art and Black contemporary modern art.[60] In his view, Dial’s blended works are both commemorative and political, as they responded to contemporary social issues of Black Americans.[61]

Similar to Driskell’s interpretations of Dial’s work is Cubbs’s essay titled “Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial,” which offers another perspective about how materials and their haphazard-like appearance speak to the horrific realities of Black Americans in the South, particularly between the late nineteenth and most of the twentieth century. In Alabama, Dial had first-hand experiences of living amidst the hostility of Jim Crowism in the early and middle 1900s. Cubbs argues that Dial “recounts many episodes in American memory, from the atrocities of slavery, Jim Crowism, and segregation to the Great Migration, the fight for Civil Rights, and the dilemmas of contemporary race relations.”[62] Cubbs argues that these histories boldly reflect in Dial’s formal choices, stating that, “Dial’s slashes of pigment become metaphoric fragments of a shattered social order, signifiers for the arbitrary violence of white supremacy.”[63] Her cynical yet crucial analysis of Dial points to a greater reality of the oppression of Black Americans in the South. This painterly technique that Cubbs notes appears throughout History Refused to Die and is most evident on the side where the white tin bird is perched. Cubbs also points out Dial’s frequently used ropes, chains, wire, and metal grids across his works, which are metaphors for confinement.[64] Alessa Pitchaman Alexander adds to these abrasive formal choices when she notes the weighted, rustic chains in Dial’s sculpture, The Blood of Hard Times (2004) (Fig. 9), which are representative of forced labor and bondage.[65] Alexander writes, “Dial’s characteristically evocative use of carefully chosen materials speak about—and represent—the subject at hand, in this case, the difficult and violent labor of steel manufacturing, allows his work to move beyond both the realms of abstraction and literal representation.”[66] Lampkins-Fielder also adds that Dial saw himself as a “sort of scavenger or pick-up bird” and acknowledges his practice of recycling resources available to him within the context of his farm household in the rural South.[67] In Rizvana Bradley’s dissertation, she equates Dial’s discarded objects with African American artists living at the margins of society in the rural and urban South. Bradley explains that impoverished African American artist communities in the South were largely ignored and forgotten like discarded objects.[68] Many of Dial’s paintings and sculptural pieces are directly in conversation with histories of the slave industry, economic disparities, workplace discrimination, and brutality towards Black Americans. Dial’s Heading for Higher-Paying Jobs (1992) (Fig. 10) and Monument To The Minds Of The Little Negro Steelworkers (2001-2003) (Fig. 11) are prime examples that embody these meanings of Black exploitation and labor demands.

Driskell, Cubbs, and Alexander all mention the subject of labor and the unjust histories of the Black labor force in the South, but this subject seems most acknowledged in the work of Herman and Beardsley. Herman considers Dial’s life history in the context of a larger racist and hostile labor environment within Alabama. From the second half of the eighteenth century to the twentieth century, railroad and agricultural industries dominated throughout the state, both of which were dependent on Black labor.[69] Black Americans living within the so-called Black Belt region in Alabama gravitated toward both industries because they were a main area of employment; however, low-wage labor and lack of upward mobility proved difficult for Black populations living in the region.[70] In the case of farming, Herman emphasizes that Dial’s experiences tilling soil as a young child were inextricably linked to the constant exploitation of Black American sharecroppers.[71] Herman writes, “Dial’s commentaries are complex and thoughtful fusions of ideas and emotion. They are haunted works, and what shadows them is the uncertain relationship they establish between history and memory.”[72] As Herman’s quote makes clear, Dial’s work engages both with his own life history and with a dark past of industrial histories that was part of Alabama. Herman’s ideas of Black labor reflect within History Refused to Die with its showing of visceral chains, fabrics, sharp edges, and dirt traces along the okra roots.

In addition, Beardsley contributes his views on Dial’s working history in his essay titled “His Story/History” which is part of the exhibition catalog, Thornton Dial in the 21st Century. In this essay, Herman provides a brief overview of the growth of steel and iron production in the Black Belt region during the nineteenth to the twentieth century and associates this history with Dial’s practice.[73] Bessemer’s rich deposits of red iron ore in the town meant that commercial manufacturing of pig iron and steel could begin to take form.[74] According to a pamphlet from 1890 titled Mining and Manufacturing: Advantages at Bessemer In the Heart of Mineral Alabama, iron ore was mined and loaded into tram cars that were transferred to Bessemer’s furnace locations such as Chattanooga, Gadsden, Birmingham, and Ensley City.[75] An abundant source of iron ore, coal, and limestone in Bessemer’s outer areas contributed to the founding of the railroad car factory known as the Bessemer Pullman Standard Plant in 1929 (Fig. 12). This factory was one of the building facilities that was part of the greater Pullman Car Company from the twentieth century. Herman notes the social issues of labor, which included the discrimination and division of labor between white and Black workers, low wages, and inadequate technical training needed for production.[76] Beardsley does not elaborate on which workers specifically handled different machinery at the Plant, but his text proves critical for understanding the labor restrictions Black workers faced. Dial described his time at the Plant stating, “only things Negros do could was hard, nasty jobs, cleaning up, sweeping. White folks did the welding. I have always been a helper. And I wasn’t make much money as the White people.”[77] Dial began his work at the Pullman plant around the time a strike took place and witnessed the unjust treatment of its workers.[78] At the Bessemer Pullman Plant, the decision to restrict Black workers to certain types of labor was based on racist policies that were implemented by higher-level company officials.

Dial was attentive to the historical realities that involved the unjust treatment of Black Americans throughout modern history and into his present moment, and many of his works attend to Black American history and African American identity. Scholars have responded to Dial’s narrative accounts by attempting to locate distinctive meanings that are associated with his choice of materials. The tendency of scholarly arguments to continuously attach Dial with racially oppressive history raises the issue of discussing objects as direct symbols to Black historical oppression. Although Black American history is essential and important for investigating Dial’s work, an additional layer of study can be brought forth that does not solely tether Dial’s racial and social class identity to his work. Instead, in the following chapter, I reference the locations in which Dial used objects as opportunities for creative expression and connection to other artists such as Holly and Bendolph. Approaching these associations through autobiographical evidence and scholarly texts allows for a more local examination of his labored process that was shaped by greater socio-political histories of racial struggle in the American South.

[56] Dial, Metcalf, Cubbs, Driskell, and Tate, Hard Truths, 38.

[57] For more on the relationship between Thornton Dial and Southern Black histories see Thornton Dial, William Arnett, and Joanne Cubbs. Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, 2005); Thornton Dial, Eugene Metcalf, Joanne Cubbs, David C. Driskell, and Greg Tate, Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial (New York: Delmonico Books, 2011); William Arnett, History Refused to Die: The Enduring Legacy of the African American Art of Alabama (Montgomery: Alabama, 2015); Raina Lampkins-Fielder, Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers (Royal Academy of Arts: London, 2023).

[58] David C. Driskell, “Giving in to the Visionary Dream” in “Giving in to the Visionary Dream: A Visit with Thornton Dial” in Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, 2011, 14.

[59] Driskell, “Giving in to the Visionary Dream”, 14.

[60] In Driskell’s acknowledgment of nineteenth-century Black ancestral art, he alludes to the functionality of the nkisi tools. The nkisi contained cultural objects that were meant to convey an expressive message that may be of about a person. See, David C. Driskell, “Giving in to the Visionary Dream: A Visit with Thornton Dial” in Hard Truths the Art of Thornton Dial, 2011, 15.

[61] Driskell, “Giving in to the Visionary Dream”, 17.

[62] Dial, Metcalf, Cubbs, Driskell, Tate, Hard Truths, 38.

[63] Dial, Metcalf, Cubbs, Driskell, and Tate, Hard Truths, 38.

[64] Dial, Metcalf, Cubbs, Driskell, and Tate, Hard Truths, 32.

[65] Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Unaccountable Modernisms: The Black Arts of Post-Civil Rights Alabama,” (PhD diss., University of California Santa Barbra), 114.

[66] Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Unaccountable Modernisms: The Black Arts of Post-Civil Rights Alabama,” (PhD diss., University of California Santa Barbra), 114.

[67] Raina Lampkins-Fielder, Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers, 14.

[68] Rizvana Bradley, “Corporeal Resurfacings: Faustin Linyekula, Nick Cave and Thornton Dial,” (PhD diss., Duke University), 176.

[69] Bernard L. Herman, “The Blood of Hard Times: Agricultural and Industrial Alabama” in History Refused to Die: The Enduring Legacy of the African American Art of Alabama (Tinwood Books: Atlanta, 2015), 43.

[70] Although the definitions of the Alabama Black Belt vary, the American historian Allen Tullos identifies the region by its geography and demographics. Tullos explains that the Alabama Black Belt was identified by its darkish, fertile soil which made it ideal for crop cultivation, especially cotton. The other identifying factor of the Alabama Black Belt was its majority Black population that spread across ten counties. Since the region’s “discovery” by slaveholders in the 1820s and 1830s, agricultural businesses relied on the enslaved Black labor and the consequences of this labor system left Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers in financial debt. See, “The Black Belt,” Southern Spaces, April 19, 2004, https://southernspaces.org/2004/black-belt/#section-the-black-belt.

[71] Herman, “The Blood of Hard Times”, 51.

[72] Herman, “The Blood of Hard Times”, 56.

[73] Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 274-299.

[74] Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 279-280.

[75] To produce pig iron, it needed three foundational elements: iron ore, coal, and limestone. Iron ore was mined using drill machinery, and then delivered to Bessemer’s furnace locations. Coal mining companies benefited from the coal coking quality where the coal was transported to Bessemer for the coking process. Limestone was also realized by miners for its material purity and was delivered to Bessemer furnaces. See, Mining and Manufacturing: Advantages at Bessemer in the Heart of Mineral Alabama (Charleston SC: Lucas & Richardson, 1890), 6-12.

[76] Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 278-282.

[77] Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 282.

[78] Beardsley, “His Story/History”