literature review

Only two exhibitions have featured Dial’s History Refused to Die but neither emphasized the autobiographical aspects of his artistic materials. Dial completed History Refused to Die in 2004 and donated his work to the Tinwood Alliance collection in Atlanta, Georgia the following year. Arnet founded the Tinwood Alliance to collect, preserve, and increase awareness of artwork by African American vernacular artists in the South.[3] Subsequently, in 2010, Arnett renamed the Tinwood Alliance the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. In 2014, the Souls Grown Deep Foundation gifted The Metropolitan Museum of Art with fifty-seven works by contemporary Black self-taught artists, including Dial’s History Refused to Die.[4]

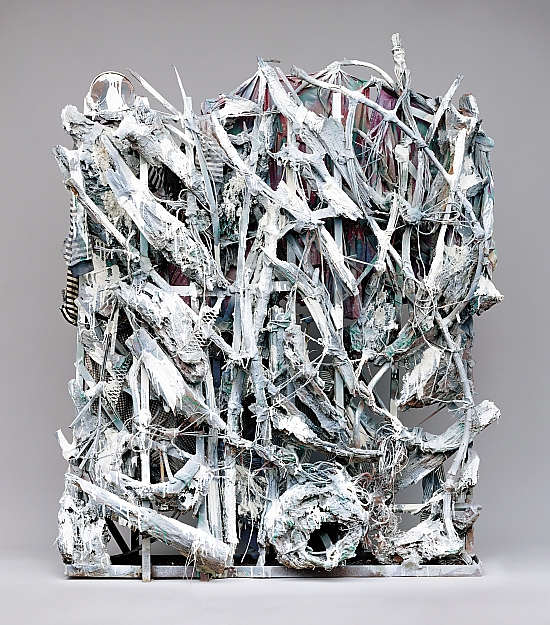

Arnett asserts that Dial’s sculpture attempts to demonstrate binaries of “past and present,” “narrative and abstract,” or “inside and outside.[5] Arnett’s son, Paul Arnett, suggests History Refused to Die is a reference to Dial’s relationship with his wife, Clara Mae explaining that “Dial patched together a theoretical backdrop made from homegrown Black art for an elder Black couple fashioned from found wood.” The inverted, dark side of the work, in Arnett’s view, acts as a visual extension of Bessie Harvey’s famous Blues song about an imagined place where no shackles exist in America. The elderly Black couple that appears within the work were rendered as protagonists who were regarded by Arnett as a free couple living in an imagined setting. By extension, Arnett felt this work was a reminder of the freed Black Americans.[6]

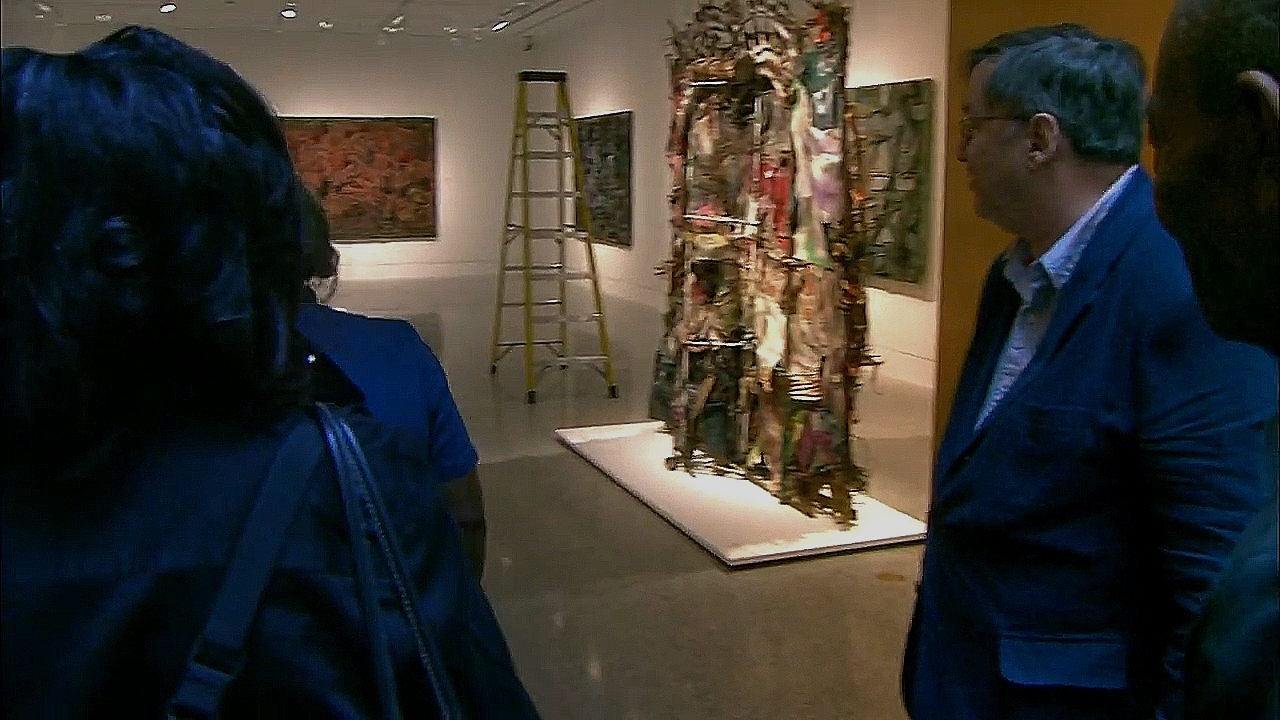

History Refused to Die was first exhibited at the Museum of Fine Art in Houston, Texas in the exhibition Thornton Dial in the 21st Century from 2005 to 2006 (Fig 3).[7] The work was displayed in the museum’s gallery spaces that focused on the Gee’s Bend quilters and Dial’s similar experiences with this community.[8] Although History Refused to Die was part of this space with the quilts, there was no mention of how the Gee’s Bend quilters are referenced in the work.[9]

Later in 2018, the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized an exhibition titled History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation that was curated by Randall Griffey, Cherly Finley, Amelia Peck, and Darryl Pinckney (Fig. 4-6). The co-curator, Griffey provides a different perspective of Dial as a modern artist, also suggesting a connection between the work’s organic materials and his African descent. He claims that Dial’s particular choice of okra roots and stalks function as a symbol of his genealogical links with Africa, African culture, and the transatlantic slave trade. Griffey also explains that the okra stalks are a symbol both of African indigenous plants and Southern cuisines. Other materials in the work, such as the fabric and wire, are described as symbols of African diasporic ties.[10] These formal interpretations of his African descent are not new to Dial’s work, and such analysis may stem from his comments about Black slave history. Further, in the exhibition catalog for History Refused to Die, Griffey recounts the kidnappings of Africans for enslaved labor and enslaved people having to navigate a new continent to survive the institution as a whole. A similar interpretation is found in a recently published dissertation by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander titled Unaccountable Modernisms: The Black Arts of Post-Civil Rights Alabama. Alexander explains that the inwoven materials in History Refused to Die communicate the cultural strength of the Black diaspora and emphasizes that the title is a statement about the legacy of Black oppression and the persistence of White supremacy into the present day.[11]

The Met exhibition aimed to pair Black self-taught artists with white European modern artists such as Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) and Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), thereby leaving labor and creative communities, two critical aspects of Black art, unexplained.[12] The exhibition presentation of Dial’s History Refused to Die alongside Gee’s Bend quilts and sculptures lacked in their elaboration of labor and creative communities.[13] For example, exhibition statements and labels did not draw on Dial’s social relations with Holly, and the only mention of labor occurred in Holly’s assembled work African Mask.[14] Comparing different European artists was an attempt to establish a similarity in stylistic practice, but this quickly overlooked the complex social-cultural histories of American Black self-taught artists.[15] While this exhibition aimed to recognize the creative talents and resourcefulness of Black self-taught artists in the South who were each part of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, it did not engage with the significance of the individual artists’ life histories and show what such histories suggest for their artwork’s social-political connections. This exhibition showed that the artists of the exhibition were multifaceted in their formal approaches to their art, but it failed to establish a strong link that bound together the autobiographical experiences of labor and creative agency. This capstone elaborates on the connections between Dial’s experiences of labor and artistic production, asserting that History Refused to Die integrates historical objects associated with his work in agriculture, heavy industry, and domestic labor to convey links with the Gees Bend quiltmakers and Black vernacular yard artists.

When Dial met more art collectors, curators, and art historians in the late 1980s, he then became increasingly integrated into art historical literature on American folk and self-taught art. Early scholarly debates about placing Dial’s artwork within the American art historical canon began in the early 1980s.[16] Disputes over where Dial fit into the art historical canons appear in texts such as African American Artist: The Work of Thornton Dial in Context, Images of the Tiger, and Testimony.[17] Art collector Paul Arnett, the American art historian Lowery Stokes Sims, poet Amiri Baraka, the American art critic Thomas McEvilley, and artist Judith M. McWillie contribute varied opinions about categorizing Dial’s artworkArnett, Sims, Amiri Baraka, McEvilley, and McWillie each argue that untrained art practices had a place within the American art canon and assert that the creation of assemblage art by Black self-taught artists in the South addresses a more extensive history of Black struggle that was excluded from art historical studies.[18] Labels such as “outsider” and “folk” are frequent terms used to describe artists who created these artworks. Nevertheless, in this evaluation, some scholars, such as Judith McWillie, wonder if such terms are appropriate to apply to Black artists in the American South.[19] Other scholars, including Amiri Baraka and McEvilley, made use of less demeaning terms such as “self-taught” or “Black vernacular.”[20] “Self-taught” has been increasingly used since it grants the artists agency and creates a distance from inadequate European art label traditions.[21] Such scholarly labels are fraught with their own individual meanings and assumptions about artists, but these debates brought forth another scholarly discussion on what autobiographical objects reveal about the Black struggle in the American South.

Rather than engaging with art historical categories, Dial made use of the term “things,” meaning that there is a twofold understanding of the materials in History Refused to Die: the materials both respond to a history of Black life, as well as functioning as art.[22] The word “things” can be attributed to Dial’s engagement with material surfaces to address metaphorical concepts related to multiple topics, such as labor. Using the term “things” can also encompass Dial’s interest in the materiality of a specific object. Amiri Baraka attends to “things” and explains they are what Dial used to make “statements about the world he was in.” Further, he argues that Dial’s day-to-day contact with the world allowed him to use things as a visual expression for his experiences.[23] The material surface of Dial objects would frequently change throughout his work, and many of his other works arguably blend bold paint strokes but History Refused to Die uniquely differs. For example, Dial’s New Generation, (2002) (Fig. 7) and Trip To The Mountaintop (2004) (Fig. 8) show assembled pieces of wood, rope, tin, steel, wire, and clothing that had been painted entirely over. Unlike these works, Dial’s History Refused to Die shows that he allowed the viewer to see the material status of iron, tin, steel, wood, quilts, and roots. Other details show twisted wire and nailed wood, which further suggest that Dial intended for his audience to witness the “things” and its industrious quality in History Refused to Die.

[3] “Who We Are,” Tinwood: Changing the way The World Think About Art and Culture. Internet Archive Wayback Machine, accessed September 9th, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20120614203127/http://www.tinwoodmedia.com/Tinwood-Who-We-Are.html.

[4] Dial was familiar with the Tinwood Alliance as it had been established by his art collector, William Arnett. The Tinwood Alliance was renamed the Souls Grown Deep Foundation in 2010 and was established by Arnett. As a result of this change, Dial’s work became part of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. See, Metropolitan Museum of Art. “History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/653729.

[5] Thornton Dial, William Arnett, and Joanne Cubbs. Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, 2005), 21, 170-171.

[6] “Thornton Dial,” Souls Grown Deep,” accessed October 13, 2024, https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/artist/thornton-dial.

[7] Thornton Dial, William Arnett, and Joanne Cubbs, Thornton Dial in the 21st Century.

[8] Alabama Public Television, “Mr. Dial Has Something to Say,” YouTube Video, 59:11, Alabama Public Television, “Mr. Dial Has Something to Say,” https://www.pbs.org/video/alabama-public-television-documentaries-mr-dial-has-something-to-say/.

[9] Alabama Public Television, “Mr. Dial Has Something to Say,” YouTube Video, 59:11, Alabama Public Television, “Mr. Dial Has Something to Say,” https://www.pbs.org/video/alabama-public-television-documentaries-mr-dial-has-something-to-say/.

[10] Griffey, “Self-taught and Modern” in History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, (Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, 2018), 22.

[11] Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, “Unaccountable Modernisms: The Black Arts of Post-Civil Rights Alabama,” (PhD diss., University of California Santa Barbra, 2018), 164.

[12] Although there were twenty quilts by the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers on view, the Metropolitan Museum of Art did not include those by Mary Lee Bendolph, whom Dial met in 2001. See, “Mrs. Bendolph,” accessed October 19, 2023, https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/artist/thornton-dial/work/mrs-bendolph. See, Randall R Griffey, “Self-Taught and Modern” in My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), 2018, 22.

[13] Scholarly interpretations surrounding Dial’s History Refused to Die remain scarce, even as the artwork provided the title of a 2014 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artists in the exhibition were Thronton Dial, Lonnie Holly, Joe Minter, Nellie Mae Rowe, Ronald Lockett, Purvis Young, Annie Mae Young, Linda Diane Bennett, Emma Lee Pettway Campbell, Mary Elizabeth Kennedy, Lucy Mingo, Lola Pettway, Lucy T. Pettway, Loretta Pettway. See, Cheryl Finley, Randall R Griffey, Amelia Peck, Darryl Pinckney, My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), 2018.

[14] “African Mask,” accessed October 19, 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/653735?ft=*&oid=653735&pkgids=490&pos=9&nextInternalLocale=en&pg=0&rpp=20&offset=20&exhibitionId=%7Ba14fcea9-f132-4a22-80f4-7e668eeb100c%7D.

[15] Scholars attempted to show that both Black self-taught artists and modern European artists were similar in that they used unconventional everyday objects in their work and were experimenting with depictions of real-world environments. However, these comparisons are inadequate because of the large differences between the two groups of artists. The two mentioned European artists and the Black self-taught artist of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation had been different in how they viewed their practice and how they engaged with real-world events and spaces. See, Randall R. Griffey in “Self-Taught and Modern,” in My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), 21.

[16] Judith M. McWillie, “African American Art and Contemporary Critical Practice,” in Testimony: Vernacular Art of the African American South (New York: H.N. Abrams, 2001), 11-30.

[17] For more debates on the art historical categorization of Thornton Dial see, African American Artists: The Work of Thornton Dial in Context,” Drafts, circa 1990. Lowery Stokes Sims papers, 1967-2019: African American Artists: Box 6 Folder 20. Archives of American Art; Thomas McEvilley, “Proud Stepping Tiger: History as Struggle in the Work of Thornton Dial,” and Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones), “Fearful Symmetry: The Art of Thornton Dial,” in Thornton Dial: Image of the Tiger (ABRAMS, 1993), 8-65; Judith M. McWillie, “African American Art and Contemporary Critical Practice,” in Testimony: Vernacular Art of the African American South (New York: H.N. Abrams, 2001), 11-30.

[18] Paul Arnett, “An Introduction to Other Rivers” in Souls Grown Deep African American Vernacular Art of the South (Tinwood Books, 2000), xiii-4.

[19] Judith McWillie notes that using “outsider art” and “folk art” labels in the context of Black American art context requires more clarification and exploration since these terms were applied to European modern art contexts with a particular modernist epistemology. As art critics used labels with European connotations to write about Black self-taught art, it ignored the social complexities of Black vernacular artists in the South. See, Judith M. McWillie, “African American Art and Contemporary Critical Practice,” in Testimony: Vernacular Art of the African American South (New York: H.N. Abrams, 2001), 14-24.

[20] Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) supported the use of self-taught as a label for Black vernacular artists with no formal training in studio art because the label for Dial represented an “unlicensed” pursuit to create and make statements of the world from found objects. See, Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones), “Fearful Symmetry: The Art of Thornton Dial,” in Thornton Dial: Image of the Tiger (ABRAMS, 1993), 34.

[21] Finley, Griffey, Peck, Pinckney, My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018, 21.

[22] While scholarly conversations about how to refer to Dial’s artwork took place, Dial remained impartial toward them. In other words, Dial was not directly engaging in conversations about finding a distinctly African American art style or deciding which canon of art his work fell under. Dial did not oppose the art historical categories of his work because he had not been familiar with the terms. See, Thornton Dial, William Arnett, and Joanne Cubbs. Thornton Dial in the 21st Century, (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, 2005).

[23] Amiri Baraka, “Fearful Symmetry,” 41.