Microtargeting:

Politics of Participation, Politics of Polarization

Brian Hamel

Abstract

In this paper, I argue the microtargeting tactics used by political campaigns are both a positive and a negative for the political process. Microtargeting increases the level of political participation, and, in turn, voter turnout by disseminating information to voters, by intensifying voter preference, and by mobilizing voters. Yet, the same microtargeting techniques that increase political activism also have a negative effect on the electoral process because microtargeting enables a campaign to target and intensify both niche groups and wedge issues. Ultimately, the targeting of these groups and these issues greatly influences voting behavior and allows a campaign to avoid common themes and instead opt to focus on the most divisive issues of all. Microtargeting strategies in political campaigns are nothing new; however, with time and technology also comes a much higher level of influence and effect. Going forward, it is expected that the tools at the campaigns’ disposal as well as the role and significance of these tools in the political process will only increase.

In the aftermath of the 2012 presidential election, microtargeting strategies have been heralded by political consultants and the pundit class alike as the reason for President Obama’s decisive re-election (Young). And indeed, microtargeting, a simple, yet incredibly complex term, does, in fact, hold the key to victory for politicians in the 21st century. Microtargeting tactics, however, are not entirely a godsend to American politics. The effects of microtargeting tactics are two-fold. On the one hand, microtargeting tactics enable a campaign to deliver pertinent information to specific voters, thereby increasing participation in the political process and voter turnout. Conversely, in using microtargeting techniques, campaigns foster a level of polarization within the electorate by encouraging political participation with only divisive issues in mind. In practice, campaigns are able to microtarget because of “Big Data,” the combination of public data (zip codes and other demographic information), private data (what kind of car a voter drives, where the voter prefers to shop, etc.), and online data (what websites the voter visits and how the voter does or does not interact on social media) (Foughy). The combination of this data allows a campaign to, according to Chris Cillizza, a nationally recognized reporter for The Washington Post, to “unravel your political DNA” (Cillizza). A campaign will then take such voter DNA to target voters with specific messages, and essentially, according to Sasha Issenberg, the author of The Victory Lab, “have a different conversation with everyone on the block” (qtd. in Hinman).

Take Nella Stevens for example. Stevens, a 52-year-old voter from Charlotte, North Carolina was an undecided voter last fall (Wise and Helling). In trying to make a decision last November, Nella found herself being followed as she surfed the Internet because, in trying to persuade Stevens, both the Obama and Romney campaigns were searching for that one issue that would sway her vote. Nella remarked, “If I go to one site to research or I start Googling his views on things, then for the next day Obama just scrolls across my screen, and the same thing for Romney. I started noticing it, and it’s very funny after a while. I was like, ‘This is very strange’” (Wise and Helling). Strange, indeed. But, what Nella does not know is that this mechanism of microtargeting is pointed and deliberate. And it is the pointed and deliberate nature of it all that has a profound effect on American politics.

Microtargeting techniques can serve as a positive for democracy by encouraging political participation and increasing voter turnout by homing in on three key campaign-controlled variables: information, intensity, and mobilization.

While the verdict is not yet in on whether the voting populace is ill- informed or well-informed, one can discern from years of research that an increase in information has a positive effect on political participation and voter turnout. In “The Effect of Information on Voter Turnout: Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” David Dreyer Lassen, a professor of Political Economics at the University of Copenhagen, uses empirical estimates based on survey data from a Copenhagen referendum election to conclude that there is a “sizable and statistically significant casual effect of being informed on the propensity to vote” (103). Indeed, turnout among informed voters, according to Lassen’s data, is 78.4%, whereas turnout among uninformed voters is 69.0% (110). Indeed, the level of information in the political process has an effect on participation because the “learning of candidate stances increases the amount of information at voter’s disposal” (Strauss 19-20).

Information for the sake of information, however, is not good enough. While Lassen’s data is compelling, and the logic behind the relationship between information and voting behavior quite commonsensical, the campaign must use microtargeting information to understand voters both personally and privately with one goal in mind: to intensify voter preference. Campaigns must provide a voter the information that matters most to them by creating a level of intensity that provides a deep connection between the candidate and the voter. In The American Voter Revisited, a 2008 book by a quartet of accomplished political scientists, it is noted that “intensity of voting preferences catches an important motivational factor” (Lewis-Beck et al. 90). Most notably, research shows that as intensity of preference rises, the percentage of those voting relentlessly increases, so much so that the percentage voting ends up to be nearly 100% (Lewis-Beck et al. 91).

In 2004, the Bush re-election campaign – known in political circles as the pioneers of political microtargeting – microtargeted black Democratic voters in the key battleground state of Ohio (Edsall). In 2000, Bush received only 9% of the black vote in Ohio (Edsall). But in 2004, Bush received 16% of the black vote (Edsall). The Bush campaign did not achieve this modest, yet potentially decisive, result by simply paying more attention to black Democratic voters in Ohio. No, the Bush campaign targeted black Democratic voters on the issue of same-sex marriage, an issue at the time that was of particular concern to the typically socially conservative black Democrat (Edsall). This shows how microtargeting enables a campaign to get a clear understanding of each voter on individual level. As such, a campaign can tailor information and deliver the appropriate information and message to the right audience. This strategy gives a campaign the chance for their message to be heard. In this way, campaigns use what Raymond Nickerson, a Tufts University psychologist, calls confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the “seeking or interpreting of evidence in ways that are partial to existing beliefs” (Nickerson 175). Thus, if a voter is targeted with advertising on an issue he or she is passionate about, or more importantly, that confirms his or her own belief, then the voter is more likely to respond favorably and more likely to vote for that candidate.

With the intensity of an issue in mind, it is important to note the tone of the message and information being delivered to a voter. Political scientist Gregg Murray and computer scientist Anthony Scime published an article titled, “Microtargeting and Electorate Segmentation: Data Mining the American National Election Studies,” in which they argued that “overall participation may be improved by communicating more effective messages that better inform intended voters” (143). They use “decision tree” analysis—a decision tool that considers both the chance of event outcomes and the consequences of such decisions—to determine how a voter votes, and most notably, they argue that through the tone of the message a campaign can persuade (particularly through negative advertising on the opposition) a voter in their direction (Murray and Scime 157). The Bush campaign used microtargeting techniques to not only understand the electorate and to target information with a eye towards what matters to individual voters, but also to determine the tone that will intensify voter preference and, in turn, increase voter turnout.

But even given the importance of tailored messages and information to foment intensity among voters, a campaign must still energize, engage, and mobilize voters. Mobilization is one of, if not the, key concepts of political participation. If a campaign does not mobilize its voters before and on Election Day, the prospects of victory will inevitably decrease. Microtargeting allows campaigns to mobilize voters because it gives campaigns the opportunity and the necessary information needed to make an appeal for engagement in the political process on a level that is both meaningful and personal. In 2008, the Obama campaign masterfully used microtargeting techniques to engage an entirely new block of voters in the electoral process. For example, the Obama campaign created social networks that included segments of Obama supporters (Spiller and Bergner 69). These segments of supporters were motivated “to team up with other individuals to cohost events for fundraising, volunteer recruitment, information dissemination” (Spiller and Bergner 69-70) and the like. Furthermore, on Election Day, supporters were asked to contact a list of five likely Obama supporters who lived on their street and shared common interests (Spiller and Bergner 69). The goal was to encourage and mobilize people to vote, and in doing so, participation in the electoral process simultaneously increased. The Obama campaign combined geographic information and issue interests to engage people in the political process. This engagement and activism is not the end, however. This engagement leads to the most important action of all: voting.

President Obama faced a tough challenge for re-election. The Obama re-election team knew that in order to win in 2012, they would need to re- energize and mobilize the young voters and voters of other key demographics that led the President to victory in 2008. To do so, the campaign developed a voter turnout program that relied on microtargeting techniques as the primary means of demographic voter outreach. The results were profound: the Obama re-election team, despite overall national turnout among Democrats down 3.5 million voters (Wakefield), was able to increase turnout among young, black, Hispanic, and urban voters to 70% in the key swing states (Young).

Similarly, in the 2012 Republican presidential primary, Michele Bachmann ran a series of Facebook and YouTube pre-roll advertisements in advance of the August 2011 Ames, Iowa Straw Poll. The Iowa-centric Bachmann ads were targeted to Republican primary voters who lived near Ames, Iowa and frequently surfed the Internet for political news (Smith and Schultheis). Bachmann won the Straw Poll, and the results of the web advertisements were telling. Indeed, “more than half a million Iowans saw the videos, and roughly 75 percent sat through them to completion” (Smith and Schultheis). Of course, the effect of the Bachmann’s microtargeting efforts on the straw poll results are difficult to measure, but one has to assume these efforts did not hurt her in mobilizing voters to support her.

Microtargeting is a tool that gives a campaign the power to directly influence political participation and voter turnout. By understanding the electorate and its preferences, campaigns can disseminate the right information to the right audience, campaigns can intensify voter preference, and campaigns can mobilize its supporters in a way that makes civil duties more personal. But, one must also consider the deeper implication behind this seemingly positive development in electoral politics. Ultimately, microtargeting is not an entirely positive facet of modern American politics because political microtargeting increases the level of participation for all of the wrong reasons and creates polarization among the electorate that transcends political life.

David Helfenbein, a longtime aide to Hillary Rodham Clinton, observed in his journal article “Political Polarization in America, Through the Eyes of a President,” that there are three types of polarization: (a) among the public (that is, voters and non-voters), (b) among the electorate (the voters), and (c) among the elite (the politicians and the party) (19). Helfenbein considers these three interconnected, yet he argues that they should be considered as separate and independent entities (19). In the case of microtargeting, however, it seems that microtargeting tactics create a level of polarization among the electorate that is entirely caused by and dependent upon the actions of the elite (in this case, the campaigns). Aaron Strauss, the director of the Decision Analytics team at The Mellman Group, a research-based strategy firm, introduces the concept of cue- taking and argues that “since microtargeting increases polarization and elite affection, advancements in campaigns’ targeting abilities may increase the probability of cue-taking from elites” (22). The elite, essentially, polarize the electorate and create a division between voters by prescribing tailored messages to voters that pit one against the other. Thus, voters vote based on the cues – the targeted messages – delivered by the elite.

The elite, i.e. the campaigns, create this level of polarization with cue- taking, first and foremost, by the way in which the voter profiles are composed. Political consultants will argue that microtargeting tactics allow the campaign to get a better understanding of the issues that matter to the voting populace. Yet, in the audiences campaigns create from voter profiles, the trend is clear. These audiences are representative of one of two things: (a) single issues, often small, insignificant ones that have little impact on actual policy, or (b) ideologically wayward rhetoric and issue positions. Neither is a positive.

For example, in 2004, the Kerry campaign, in conducting its microtargeting efforts and in segmenting the electorate, identified a group of individual votes that they called “Christian Conservative Environmentalists” (Levy). Additionally, Mitt Romney’s campaign, in what can easily be considered the strangest target subset of them all, identified a group of voters in an area of northern Virginia who were concerned with the spread of Lyme Disease (Hinman). In both cases, the two campaigns were able to target single-issue voters. Throughout the campaign, the Romney campaign had been targeting this tiny pool of voters with a platform focused on “getting control of this epidemic that is wreaking havoc on Northern Virginians” (Hinman). These types of issues, these groups of people, are not the ones who typically dominate and determine national elections, but microtargeting allows these people to be identified – and divided from the rest.

In 2004, the Bush campaign created a group called “Flag and Family Republicans” who were targeted with advertising about an amendment that would ban flag-burning (Lundry). Certainly, many people hold the same position on this issue as the “Flag and Family Republicans,” but this group was targeted, it seems, because they regard this sensitive issue as being important. This not an issue a candidate will run a national campaign on. Indeed, though it is an ideologically extreme issue, it is one that microtargeting techniques enable a campaign to exploit.

Additionally, as campaigns have been granted more and more access to consumer information, the creation of niche groups and ideological extremes has extended to patterns of apolitical life as well. Now, as explicated by veteran political journalist and Columbia University professor Thomas Edsall is his piece, “Let the Nanotargeting Begin,” voting behavior is being determined by what kind of car you drive, what television shows you watch, and what kind of alcohol you consume (Edsall). This tactic takes stereotyping to an entirely new level: where campaigns look at the differences in taste between people to prepare voting profiles so they can target groups of voters accordingly. Indeed, microtargeting techniques have been able to identify that a liberal is more likely to drive a Subaru or a Honda, while a Republican is likely to drink Miller Lite and a Democrat Miller High Life (Edsall). The introduction of consumer information into political campaigns presents voters with a challenge: they are constantly being put into categories by the elite no matter what they do or what they think.

The creation of these niche groups allows campaigns to intensify these niches, and ultimately, lead a voter to pulling the lever for the wrong reasons. Consider the previous example of the Bush 2004 re-election campaign in Ohio. The Bush campaign successfully increased their share of the vote among black voters by targeting them with information. But, the information targeted to them focused entirely on the major wedge issue of the 2004 campaign: same- sex marriage. Certainly, at this time, black voters overwhelmingly opposed same-sex marriage, but it was not, given the state of national security, the most important issue facing voters. Yet, for black Democrats in Ohio, it was made the most important issue because the Bush campaign focused the black Democratic target audience relentlessly on the issue. By making same-sex marriage the most important issue, the Bush campaign utilized anchoring, a term used by psychologists to describe the tendency “to rely too heavily . . . on one trait or piece of information when making decisions” (“Anchoring Bias”). The campaign intensified the issue in the minds of black Democratic voters. Thus, the campaign made sure this target audience would be universally focused on this issue, on the piece of information given to them on this issue, when deciding whether to vote for George W. Bush or John Kerry.

The intensification of issues again raises the idea of cue-taking from the elites. When a campaign uses microtargeting tactics to segment the electorate into groups, the campaign is exploiting the beliefs of the electorate, and by tailoring messages that pertain to said beliefs, voters ultimately take cues from the elite on what is most important in voting. Indeed, this intensifying of information leads voters to vote, but not because they necessarily believe Bush should be re-elected, but rather because the campaign divided them into an audience, and within that audience, voters are told what is to be the main consideration in voting choice.

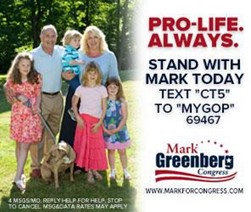

When campaigns use microtargeting as the means for victory, campaigns simultaneously polarize the electorate and, in turn, concede it is not possible to win with a common theme. In 2012, I served as Digital Director for Mark Greenberg, a Republican congressional candidate in Connecticut. Locked in a tight, four-way Republican primary, it was our goal to rally and turn out the conservative base of the Republican Party. As Greenberg was the only pro-life candidate in the race, much of our microtargeting work was done to find and follow – mainly on the Internet – the pro-life base of the party among likely voters. From there, these socially conservatives voters were targeted with ads promoting Greenberg’s pro-life stance (see advertisement below), and in some cases, opposing the pro-choice stance of our three opponents (Targeted Victory). In doing so, we conceded that there was no unifying message, even among voters of the same party, that could deliver us the roughly 9,500 votes needed to win the primary. In essence, the campaign sought to polarize the electorate by creating a micro- constituency of those who fit into our mold, while ignoring – in large part – the rest of the Republican electorate simply because they did not fit into our niche. The tactic worked, to a certain degree. Internal polling indicated that Greenberg did well among conservative pro-life Republicans, but poorly among moderate Republicans, a constituency that can prove to be important in Connecticut. Greenberg fell short on primary day – perhaps because the microtargeting strategies used divided the electorate in half. This example is but one demonstrating the power of microtargeting as an engine for political polarization.

The basis of microtargeting rests on the idea that in order to win, a campaign must run campaigns within campaigns, where cues are delivered to segments of the population that exploit and intensify wedge issues and cater to ideologues that rarely have an influence in political discourse. Ultimately, the electorate becomes a large whole made up of many small parts. Undoubtedly, this development should cause concern for all worried about the well-being of the electoral process and it this development that will be at the forefront of discussion over the political culture of the United States.

A key question thus remains: what do voters think of microtargeting and what does it mean for politics in the United States? Joseph Turow, a professor of Communications at the University of Pennsylvania, released a July 2012 report titled “Americans Roundly Reject Tailored Political Advertising” which found that that 86% do not want political campaigns to tailor advertisements (3). Turow wonders what this widespread disapproval from the public means. Given such a clear divide between what is practiced and what voters believe should be practiced, it is possible that as the scope of microtargeting continues to expand with the growth of technology, voters will become even more disillusioned in the nation’s electoral system (Turow 26). Ultimately, there is potential for a rapid and even more pronounced decrease in citizen-to-politician trust, which would likely be devastating to the nation’s historically stable process of elections.

Much to Turow’s chagrin, microtargeting tactics are here to stay. Jim Walsh is the Cofounder and CEO of DSPolitical, a Democratic digital consulting firm and “Home of the Political Cookie” (DSPolitical.com). I corresponded with Walsh via email and from the get-go, Wash was keen to note that “at the end of the day, the reality on the ground is that [microtargeting] isn’t going anywhere,” especially considering that it is not a new trend (Walsh). Indeed, according to Chris Cillizza, during the 1976 presidential campaign, Pat Caddell, Jimmy Carter’s pollster, created a chart that outlined what issues were important (and which were unimportant) in each region of the country (Cillizza). Caddell’s albeit cruder form of microtargeting enabled the campaign to better understand the electorate and by extension, allowed Carter the candidate to campaign and persuade voters more effectively as he traveled the country.

As for microtargeting in the future, Walsh wonders what the critics propose as the alternative. Why would a campaign spend a limited budget on speaking to the entire universe of voters when a certain percentage are already “deaf to your message?” (Walsh). Moving forward, Walsh expects that the technology and how it uses the data will grow to be more intelligent and that “campaigns will devote at least 25% of their total media budgets to online advertising in 2016” (Walsh). Thus, the amount of money designated by a campaign to microtarget and tailor messages to voters (particularly on the web) is only likely to increase with each election cycle.

And Walsh is right. Microtargeting tactics, no matter the consequences – positive, negative, or otherwise – are here to stay. The ultimate, and truly the only, goal of a political campaign is to win – no matter the cost. Campaign tactics such as microtargeting are campaign-controlled; thus, microtargeting tactics will remain an ever-growing aspect of the electoral process so long as they are effective. There is no evidence that this trend will let up. Soon, “Big Data” will soon become “Bigger Data,” and with that the advances in technology will enable a campaign to expand and enrich its microtargeting program. One must praise microtargeting for the good it does, the good of political participation, and indeed, the good that keeps democracy afloat. Yet, one must be remain skeptical of microtargeting and be critical of its tendencies to venture into the polarizing fields of political extremism.

In the end, with each passing election cycle, the use of microtargeting will likely continue, and for Nella Stevens, the undecided swing-state voter from North Carolina, and the millions like her, mining the Internet for information about candidates and elections will only get stranger. Political scientists and political pundits will continue to express disapproval over the use of microtargeting, but in the words of Jim Walsh, engaging in the discussion over the consequences of this phenomenon, is “an entirely academic exercise” (Walsh). Why? Because microtargeting works.

Works Cited

“Anchoring Bias in Decision-Making.” Science Daily. Science Daily, n.d. Web. 21 April 2013.

Cillizza, Chris. “Romney’s Data Cruncher.” The Washington Post. The Washington Post, 5 July 2007. Web. 6 Feb. 2013.

DSPolitical.com. DSPolitical, 2013. Web. 24 March 2013.

Edsall, Thomas. “Let the Nanotargeting Begin.” Campaign Stops. The New York Times, 15 April 2012. Web. 4 Feb. 2013.

Fouhy, Beth. “2012 Election: Campaigns Mine Online Date To Target Voters.” The Huffington Post. The Huffington Post, 28 May 2012. Web. 25 March 2013.

Helfenbein, David. “Political Polarization in America, Through the Eyes of a President.” College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal (2008): 1-93. Web. 23 March 2013.

Hinman, Katie. “‘Microtargeting’ Lets Pols Turn Data Into Votes.” ABC News. ABC, 22 Oct. 2012. Web. 26 March 2013.

Lassen, David Dreyer. “The Effect of Information on Voter Turnout: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 49.1 (2005): 103-118. JSTOR. Web. 22 March 2013.

Levy, Steven. “Campaigns Get Personal.” Newsweek Magazine. The Daily Beast, 19 April 2008. Web. 25 March 2013.

Lewis-Beck, Michael, et al. The American Voter Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011. Print.

Lombardi, Kate Stone. “8-Year Clinton Veteran (and Yes, He’s Just 21).” In the Region. The New York Times, 3 Feb. 2008. Web. 27 March 2013.

Lundry, Alex. “Microtargeting: Knowing The Voter Intimately.” Learn From The Experts. Winning Campaigns, n.d. Web. 25 March 2013.

Murray, Gregg and Anthony Scime. “Microtargeting and Electorate Segmentation: Data Mining the American National Election Studies.” Journal of Political Marketing 9.3 (2010): 143-166. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2013.

Nickerson, Raymond. “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology 2.2 (1998): 175-220. JSTOR. Web. 21 April 2013.

Smith, Ben and Emily Schultheis. “Targeted Web Ads: The Next Frontier.” POLITICO.com. Politico, 30 Aug. 2011. Web. 24 March 2013.

Spiller, Lisa and Jeff Bergner. Branding the Candidate: Marking Strategies to Win Your Vote. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011. Print.

Strauss, Aaron. “Microtargeting’s Implications for Campaign Strategy and Democracy.” Diss. Princeton University, 2009. Web. 20 March 2013.

Targeted Victory. Pro-life. Always. July 2012. Web advertisement. Connecticut.

Turow, Joseph, et al. “Americans Roundly Reject Tailored Political Advertising.” Annenberg School for Communications, University of Pennsylvania. July 2012. Web. 2 Feb. 2013.

Wakefield, Mike. “CPAC Postmortem on 2012 – Microtargeting, Outreach and Media Doomed GOP.” Red Alert Politics. Red Alert Politics, 15 March 2013. Web. 25 March 2013.

Walsh, Jim. “Microtargeting Techniques.” Message to the author. 23 March 2013. Email.

Wise, Lindsay and David Helling. “Microtargeting Refines the Political Campaign Game.” Midwest Democracy. The Kansas City Star, 5 Nov. 2012. Web. 4 Feb. 2013.

Young, Antony. “How Data and Micro-Targeting Won the 2012 Election for Obama.” Media Business Network. Media Business Network, 20 November 2012. Web. 18 March 2013.