The Lenses of Truth:

Photographers’ Moral Responsibility to Document Injustice in Most Situations

Lindsay Maizland

A small fire burned as the sun rose in the East. Children wearing tattered shirts whispered to two older women who smiled as they tended the flames. They, members of a Tanzanian Bushmen tribe, seemed to share secrets, while I, an outsider with white skin and blonde hair, gazed on. Our skin color was not our only difference. My clothing was clean and new. My hair was long and combed. It was early morning and the family should have been eating breakfast, but there was no food in sight. My family and I ate before hiking to meet the Bushmen and had snacks in our van. Only words filled their mouths while uncomfortable silence filled ours. They lacked basic necessities that we take for granted: food, clothing and even shelter, as they lived in caves. It was impossible to feel comfortable; to them, we were symbols of wealth. To us, they were symbols of poverty.

My camera, large and obtrusive, hung around my neck. I wanted to document them, but I hesitated because I intruded on their daily lives. Soon though, I began snapping pictures. I watched as the Bushmen patriarchs hunted for birds and snakes too small to feed the entire village, while the women and children were left to find their own sources of nutrition. I watched as the children asked their mothers for food and as the men greedily devoured what little meat they could find. “How can I help these people?,” I questioned. My family and I ended up sharing some of our snacks, but when I view the pictures today, I feel deep remorse for not helping more.

My guilt is not an isolated incident; it is a feeling that many photographers and photojournalists experience. They echo my question, “Should I help the victim or document the moment with my camera?” Although many journalists and ethicists argue that photographers’ civil responsibilities should always surpass their professional assignments, in most circumstances, photographers must document societal injustice. Photojournalists fill a role that no other professionals fill – they document the often disturbing, but very real, truth and broadcast their findings to the world. This, in turn, promotes policy change and civilian service. In a sense, photojournalists indirectly help the victims of tragedy and immediate action should not be expected of them.

The Case of Kevin Carter

Kevin Carter’s photo (Krauss).

My personal experience is indeed representative of photographers’ inner struggles, though my conflict was drastically less complicated than a professional photographer’s. Take Kevin Carter, for example, a photojournalist who shot a heart-wrenching photo of a starving, Sudanese child being stalked by a vulture. The photo, as seen above, was published in The New York Times in March 1993. Unsurprisingly, readers’ responses were widely varied. Some praised Carter for his effort, and others offered only harsh criticisms. Called the “true vulture” and described as “devoid of humanity,” Carter was widely criticized for not carrying the child to the feeding shelter that she struggled toward (Cate). Carter responded to his critics and said:

It may be difficult for people to understand, but as a photojournalist, my first instinct was to make the photograph. As soon as that job was done and the child moved on, I felt completely devastated. I think I tried to pray; I tried to talk to God to assure Him that if He got me out of this place I would change my life (Krauss).

Carter followed his “instinct” and acted as a photographer rather than carrying the child to food. Carter’s critics strongly believed that Carter neglected his duties as a human being. A conflicted Carter commented to his friend, “I’m really, really sorry I didn’t pick the child up” (Cate). Soon after receiving a Pulitzer Prize for the photo in 1994, Carter committed suicide.

Despite the widespread criticism, several journalists praised Carter. Bob Steele, the director of the ethics program at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, explained the importance of photojournalists:

There were, ideally, lots of other people to give aid, medicines, care, but nobody is going to replace the role of the journalist. The military, the aid workers, the Red Cross–no one filled the role Kevin Carter did. He was the one who got the message out to the rest of the world (Cate).

Carter’s job was to take photos of the complete devastation; others, such as United Nations Food workers and the Red Cross, should have helped the child. In fact, as Steele explained, Carter effectively broadcasted the famine to the world by publishing the photo. Funds streamed in to help feed the hungry in Africa after Carter’s photo was displayed in The New York Times and after it received the Nobel Prize. Although he did not directly help the child, Carter’s efforts saved countless of Sudanese children’s lives.

Photojournalists’ Critics

Carter’s critics and supporters illustrate that there seem to be two stances on the role of photographers in their environments: either photographers must always offer help to the victim and follow their duty as a human being, or photographers must always document the injustice and follow their professional duty. However, this is a false dichotomy; moral decisions are not that simple. As in Carter’s case, his photo eventually saved many. It is wrong to call him “devoid of humanity.” He initially followed his professionally duty, and in doing so, fulfilled his duty as a human being.

Earlier this year, a photojournalist faced similar criticisms after she documented domestic violence. Photojournalist Sara Naomi Lewkowicz spent several weeks chronicling the relationship between Maggie and Shane, an ex-convict, “while working on a project about the stigma associated with being an ex- convict” (Lewkowicz). Her project took an unexpected turn after Shane abused Maggie one evening. Lewkowicz captured the abuse, and the photos were published on Time Magazine’s “Lightbox.” Lewkowicz explained, “After I confirmed one of the housemates had called the police, I then continued to document the abuse – my instincts as a photojournalist began kicking in” (Lewkowicz). The story received 1,860 online comments, many of which criticized her and questioned why she did not stop the abuse. One commenter’s statement echoes many others: “What kind of person stands there and watches this happen?… This so-called photojournalist is an idiot who exploited Maggie and her children” (Lewkowicz).

Lewkowicz’s photo of domestic violence (Lewkowicz).

Like Carter, Lewkowicz also followed her professional “instincts.” Her photos shed new light on the prominence of domestic violence in the United States, as “many people remain ignorant (or in denial) about the real state of domestic abuse in this country” (Roller). It is too soon to tell what the consequences of Lewkowicz’s photo series are, but there is a large possibility that increased publicity will lead to governmental and social change.

Critics continue to argue that photographers aim to profit from the victims’ circumstances and therefore “exploit” them. Another argument is that photographers are inhumane for not intervening, as seen in Kevin Carter’s case. Finally, photographers are scorned for being too preoccupied with their own lives and neglect helping others.

Code of Ethics

In order to help photojournalists decide whether to intervene or document, the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) composed a “Code of Ethics,” which is, “intended to promote the highest quality in all forms of visual journalism and to strengthen public confidence in the profession” (NPPA). One standard that is especially relevant to this debate is, “While photographing subjects do not intentionally contribute to, alter, or seek to alter or influence events” (NPPA). These standards are not absolute rules but rather are recommendations on how photographers should act. Keeping that in mind, the NPPA asserts that photographers should not take action in most situations. The last standard in the Code of Ethics acknowledges the conflict between professional and moral obligations and states, “When confronted with situations in which the proper action is not clear, seek the counsel of those who exhibit the highest standards of the profession” (NPPA). Sometimes, though, it is impossible for journalists to consult others, as decisions must be made in seconds. The suggested Code of Ethics demonstrates the complexity of the issue and how photographers’ responses may vary in different situations.

Importance of Capturing Tragedy

However, despite these criticisms, photographers document the injustices prevalent throughout the world. In most circumstances, I believe that photographers should and must photograph injustice, whether a deadly famine or abusive relationship. This documentation is crucial as it gives the people being documented a feeling of worth and enables those who view the photos an opportunity to reflect on their own lives. Photojournalists communicate the issue to a broader audience, thus promoting global support.

Taking a photo is a simple way of conveying sympathy and a wish to remember. By capturing images of individuals, photojournalists demonstrate that they care. In essence, a photograph is a symbol of hope. In a recent speech at American University, broadcast journalist Anderson Cooper, who has witnessed tragedy throughout the world, stated, “Even people who are in the midst of grief, even people who are going to die tomorrow want you to know their names. They want to tell you their stories” (Cooper). Cooper continued and said that people find great peace in telling their stories to those who will actually listen to them. Perhaps a simple interaction with a photographer is all that it takes to make sufferers realize that they are important and that there is hope for the future.

Zhu Jianying, a Miao villager, beams with joy while showing me her daughter’s artwork.

I can attest to this. Last year, I travelled to a rural village in China to document the unseen aspects of the Miao minority groups. By interviewing the villagers, I learned about their hopes and dreams – one woman’s goal was to send both of her children to college; another’s dream was to travel to Beijing. Their faces lit up with joy as we snapped pictures and talked with them (see photo). Although they did not explicitly comment on the importance of our photojournalism, it was apparent that they felt appreciated and hopeful after having their photos taken.

Photos also allow viewers to gain insight on their own lives. For example, after viewing Kevin Carter’s photo, I questioned why I deserve to consume three meals a day while children throughout the world barely receive one. Because of that photo, I created a goal to waste less and truly appreciate what I have been given. In seeing what others do not have, we can further appreciate our possessions. In his book On Art and War and Terror, Alex Danchev commented on pictures’ instructional ability in helping us learn more about ourselves: “What is more, they [the people in the photos] instruct. They tell us about themselves, and they tell us about us – who we are, and who we may become; what we are, and what we are capable of” (Danchev). I could have been a starving child. I could have been a warlord who blindly kills. The photographs reveal the evils that society, “we,” is “capable” of creating. This all goes back to the feeling of guilt. Returning to Carter’s photograph, according to one author, it “begs the viewer to act” because “people felt – horror, empathy, anger” (Dougherty). After seeing people less fortunate than themselves, people typically feel strong emotions and compelled to help. It is in this way that photographs cause an influx of global support.

The Catch: Action in Some Situations

On the contrary, as I mentioned before, photographers must document injustice in most circumstances, not all; there are several situations in which photographers should and must take action. Researchers Gail Marion and Ralph Izard noted, While detached observation is thus a primary journalistic goal, situations have arisen, and will continue to arise, which might tempt a journalist to cast aside his or her cloak of objectivity and function as citizen and human being (Marion).

Throughout their essay, Marion and Izard attempt to answer the question, “The journalist in life-saving situations: detached observer or Good Samaritan?” by citing examples and quotes from various photographers and journalists (Marion). Their research, however, only reaches a tentative conclusion; they argue that journalists’ moral responsibilities depend on the situation. Another researcher, Yung Soo Kim was inspired by this article and conducted a study on how photographers, specifically, should act in certain situations. His study explored how photographers’ actions were affected by three different situational characteristics: “the presence of other helpers, the intention of the victim to engage in political speech and the possibility of intervention by the photographer” (Kim). After sending 88 photographers an online survey, Kim discovered that photographers were more likely to take photos if bystanders were already helping, if harm was self-inflicted (as opposed to accidental), and if it was impossible for the photographers to intervene (Kim). This therefore supported his thesis, “For photojournalists caught in the ethical dilemma, this study provides a clear indication that a reply of ‘it depends’ is not only reasonable, but also widely accepted by photojournalists and the public alike” (Kim). In my situation described in this essay’s opening, I decided that providing food was an ethical response because there was no other way in which I could have immediately helped.

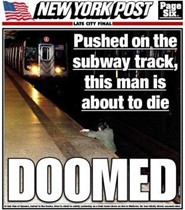

Photojournalists should be held partially responsible for injury or death if they could have easily intervened but chose not to. In a recent controversy, freelance photographer R. Umar Abbasi photographed a man who was pushed onto the subway track as a train sped into the station. The man was struck and killed. The photo was then published on the front page of the New York Post with the headline, “Doomed. Pushed onto the subway tracks, this man is about to die”

The controversial New York Post front page. (Bercovici).

Abbasi contended that he took the photos “hoping the train driver would see something and be able to stop” and that “the victim was so far away from me” (Abbasi). However, despite his comments, I believe that Abbasi should have dropped his camera and run to save the man’s life. John Long, a photographer of 35 years and chairman of the National Press Photographers Association, agrees:

If you have placed yourself in a situation where you can help, you are morally obligated. The proper thing to do would’ve been to put down the camera and try to get the guy out…. Your job as a human being, so to speak, outweighs your job as a photojournalist (Bercovici).

In this situation, the photographer should have taken action. There was a possibility that he could have helped and the man’s death was, as Kim would say, “accidental.”

Action must also be taken when the photograph will not greatly benefit society. Abbasi’s photograph did not advance society – the photograph was selfishly published for his and the magazine’s own profit. In contrast, Kevin Carter’s photo of a starving child greatly benefited society because, as mentioned earlier, it led to increased awareness and donations. Jeff Bercovici, a writer for Forbes Magazine, similarly asserted, “Newspapers have an obligation to publish images, even horrifying ones, that might affect public debate over important issues” (Berovici).

Consequences of Photographer’s Choices

In his article recounting his photojournalistic experience in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Marcus Bleasdale wrote, “I’ve always been taught that journalists must comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. With our words and pictures, we can trigger a reaction from the general public and from the leaders they elect” (Bleasedale). Rather than physically helping a single individual, photographers have the ability to drastically change the world by calling the global public’s attention to injustices and tragedies. As I established earlier, photographs convey human emotion that evokes immense sympathy; and, in turn, the photographs promote anger toward the systems that cause injustice. An example in which photographs sparked immediate change was when photographers documented injustices in Somalia during the early 1990’s. President George Bush announced that the United States would enter Somalia to help the United Nations forces in December 1992 and stated, “Every American has seen the shocking images from Somalia. The people of Somalia, especially the children of Somalia, need our help” (Perlmutter). The American people witnessed atrocities through film and called on their government to take action.

The fact that photographers’ face great emotional turmoil after deciding whether to act is another huge consequence of photography ethics. As mentioned, Kevin Carter took his own life after enduring harsh criticism and hatred. His final words in his suicide note were very disturbing and revealed that he was “haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain… of starving & wounded children” (610 Dougherty). Many photographers similarly live with the thoughts of their subjects in the back of their minds. I feel remorse for not doing more when visiting the Bushmen. Photojournalist Marcus Bleasdeale reflected again on his time in the Democratic Republic of Congo:

Scenes from this war are forever burned inside of me – children crying over the dead body of their mother…. At night these images linger in my mind. I carry them with me as I travel from village to village in Congo, where I hope each time not to stumble onto another horrific scene. Too often I do (Bleasdale).

Photographers sacrifice their mental sanity and well-being to help the public understand the horrors that permeate this world. They form relationships with individuals who rarely receive any human sympathy and might not survive the night, and they place themselves in life-threatening situations. Photographers should be the last people blamed for “not acting,” as so many critics have commented. Rather, the governments or groups that disrupt communities in the first place and the individuals who view the photographs and do nothing should take full responsibility.

Who Should Take Responsibility

The destructive groups that cause violence, poverty, and oppression should be held accountable for injustices. Photojournalists have absolutely nothing to do with conflicts; they are assigned to cover certain regions and do just that. Individuals who view photographs and do nothing should also be held responsible. A photographer’s job is complete after he documents something. The action is then passed on to the viewer – it is their decision whether they want to help or do nothing. In the words of photographer Gary Winogrand, “The photograph is not my problem… it’s yours” (Danchev). Photographers should not be isolated individuals who carry the emotional burden of conflict, death and tragedy; everyone who views photographs should also feel guilt, anger and sadness. Photographers must document cruelty in most situations. Viewers must take meaningful action within their own lives to benefit the victims and society at large.

Works Cited

Abbasi, R. U. “Anguished Fotog: Critics Are Unfair to Condemn Me.” New York Post. NYP Holdings Inc., 5 Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

Bercovici, Jeff. “New York Post’s Subway Death Photo: Was It Ethical Photojournalism?” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 04 Dec. 2012. Web. 24 Oct. 2013.

Bleasdale, Marcus. “Weighing the Moral Argument Against the Way Things Work.” Nieman Reports 58.3 (2004): 12-7. ProQuest. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

Cate, Fred H. “Through A Glass Darkly.” Harvard University Asia Center. Harvard University, 26 Aug. 1999. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

Cooper, Anderson. 2013 Wonk of the Year. American University, Washington, D.C. 19 Oct. 2013. Speech.

Danchev, Alex. On Art And War And Terror. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 15 Oct. 2013.

Dougherty, Sean T. “Killing the Messenger.” The Massachusetts Review Winter 47.4 (2006): 608-16. JSTOR. Web. 3 Nov. 2013.

Kim, Yung Soo. “Photographers’ Ethical Calls may Rest on ‘it Depends’.” Newspaper Research Journal 33.1 (2012): 6-23. ProQuest. Web. 6 Oct. 2013. Krauss, Dan. “A Pulitzer-Winning Photographer’s Suicide.” Interview by Farai Chideya. Audio blog post. NPR. N.p., 2 Mar. 2006. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

Lewkowicz, Sara N. “Photographer as Witness: A Portrait of Domestic Violence.” Time Lightbox. Time Magazine, 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 22 Oct. 2013. Marion, Gall, and Ralph Izard. “The Journalist In Life-Saving Situations: Detached Observer Or Good Samaritan?.” Journal Of Mass Media Ethics 1.2 (1986): 61-67. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

“NPPA Code of Ethics.” National Press Photographers Association. N.p., 2012. Web. 3 Nov. 2013.

Perlmutter, David D. “Just How Big an Impact Do Pictures of War Have on Public Opinion?” History News Network. George Mason University, 2005. Web. 24 Oct. 2013. <http://hnn.us/article/9880>.

Roller, Emma. “Scenes From an Abusive Relationship.” Slate. The Washington Post Company, 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.