The Loudness War

John Slights

An Introduction

In late 2012, legendary rock group ZZ Top released their latest studio album (and their first in a decade) La Futura. It was produced by Rick Rubin, and it was heralded as a critical and commercial success. Several publications called the album a “comeback” album, and it comes as no surprise that the group embarked on a massive arena tour after its release. On June 18, 2013, famed hip-hop artist Kanye West also released his latest studio album, Yeezus, which was also produced by Rubin. The album contained singles such as “Black Skinhead” and “Blood on the Leaves,” and it was a critical and commercial success.

So what do both of these albums have in common (besides sharing the same producer, of course)? Sonically, they are both disasters. What this means is that the sound quality on both of these albums is atrocious in the ears of many critics. They’re overly loud and distorted, which destroys the quality of the album.

While many audio engineers utilize excessive loudness, others have publicly spoken out against it. One of these engineers is Greg Calbi. Calbi has worked on recordings for artists such as Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Bruce Cockburn, and Paul Simon. In a recent interview, Calbi discussed what the role of an audio engineer should be. “The goal has always been to make [the recording] as loud as you can and still sound good,” Calbi said. “Nowadays, you’re making [the recording] loud before you’re making it good…and that is the root of the problem” (Calbi).

This “problem” was nonexistent in the earlier decades of recorded music, but has emerged within the last twenty-five years. This problem is referred to by many as “brickwalling,” which is a part of the dilemma known as the “loudness war,” where producers turn up the volume on sound recordings, creating a deafeningly loud and distorted effect on the recording.

Rubin, a famed producer, is one of the biggest culprits of the loudness war. He is behind the production of Black Sabbath’s 2013 album 13, the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ 1999 album Californication, and Johnny Cash’s 2010 posthumous release American V: Ain’t No Grave. All of these recordings are horribly compressed and distorted, which is consistent with the production style contained on Yeezus and La Futura. Once known for his tight and airy production style, such as the original Johnny Cash American Recordings, Rubin has traded it away in the last fifteen years for loudness at all costs.

Loudness at All Costs

The textbook example of “loudness at all costs” is Metallica’s 2008 album Death Magnetic. Widely considered to be a return to form for the band, it had all of the makings of a classic heavy metal album. It had memorable riffs, strong writing, and technically advanced playing. There was one trait it did not have – clean sound. Sonically, it is considered to be one of the poorest productions ever made. Critics and fans have complained about the lack of “warmth” contained in the recording, and perhaps rightfully so. Rubin’s production was panned, and audiophiles were infuriated, with many proclaiming it to be the worst produced album of all-time. This would lead to drummer Lars Ulrich responding to the criticism in the media:

Listen, there’s nothing up with the audio quality. It’s 2008, and that’s how we make records. Rick Rubin’s whole thing is to try and get it to sound lively, to get it sound loud, to get it to sound exciting, to get it to jump out of the speakers. Of course, I’ve heard that there are a few people complaining. But I’ve been listening to it the last couple of days in my car, and it sounds smokin.’ (Hall)

His defense of the sound quality shows that he is either in denial or completely oblivious to the overwhelming compression found on his band’s most recent album.

What is the Loudness War?

To understand the battle over sound, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of the “loudness war” and what it means. The “loudness war” is the term given to describe the louder quality of music that has been released since the mid-1990s. According to mastering engineer Ian Shepherd, “the Loudness War is a sonic ‘arms race’ where every artist and label feel they need to crush their music onto CD at the highest possible level, for fear of not being ‘competitive’ – and in the process removing all the contrast, all the light, shade and depth – ruining the sound.” In other words, it is turning up the volume on the recording and destroying the sound quality contained therein. It is not known exactly who coined the phrase and where exactly it came from, but it is the umbrella under which terms like “dynamic range” and “compression” can be found. Recently the loudness war has reached new heights, and the lack of quality sound continues to the present day. In fact, an argument can be stated that sound quality on recordings is continuing to get worse, not better.

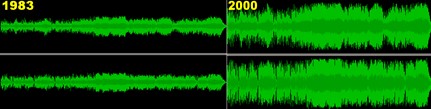

Fig. 1. The audio of The Beatles’ 1968 track ‘Something.’ On the left is the track mastered on the original 1983 CD of Abbey Road. To the right is the version mastered in 2000 for their greatest hits album 1. The 1983 version has plenty of dynamics, where the 2000 version is completely lacking in this area. Source: MK-Guitar.com

In 1982, the first compact discs were released to the public. The first CD ever released was Billy Joel’s 1978 album 52nd Street (Giles). The sound quality on the disc was considered to be phenomenal, containing plenty of dynamic range and crispness that are common attributes of an incredible- sounding disc. It was carefully mastered and transferred to disc in a manner that allowed all of the dynamic range from the vinyl recording to be carried over to the disc. This practice continued throughout the 1980s and 1990s as older albums (and new albums) were released on CD. They were cautiously transferred to disc in a way that allowed the clear sound quality to be retained. This practice continued into the early 1990s. An example of this practice can be found by comparing the sound quality of the rock group Nirvana’s 1991 album Nevermind with their 1996 live album From the Muddy Banks of the Wishkah. While Nevermind features plenty of dynamic range, From the Muddy Banks is overcompressed and lacks the airy quality of CDs released earlier in the decade (“Nirvana”).

It was in 1995 when the loudness war truly started. British alternative rock group Oasis released their breakthrough album, What’s the Story Morning Glory? The record was praised by critics (with Rolling Stone magazine later ranking it #378 on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All-Time) (“500 Greatest”) and sold 347,000 copies in its first week, a record at the time (Mugan). However, it opened the door to a trend – having a recording be as loud as possible, even if it means sacrificing the dynamic range of the album. Oasis did precisely this, mastering the record at an incredibly loud volume. Record companies caught onto this practice, and soon began insisting that all records produced follow this practice.

Terminology

There are several key terms that are vital to understanding what the “loudness war” is and the impact it has on modern recordings. The first of these terms is “dynamic range,” or “dynamics.” According to WhatIs.com, dynamic range “describes the ratio of the softest sound to the loudest sound in a musical instrument or piece of electronic equipment. This ratio is measured in decibels (abbreviated as dB) units.” Dynamic range is perhaps the most important part of a recording, as it describes the contrast between the quieter sounds of the recording and the louder passages. One of the main criticisms of the “loudness war” is the fact that all elements of the recording are mastered at equal volume. The quieter portions of the recordings are loud, and the loud portions of the recording are also loud. Both elements are mastered equally, “squashing” the dynamic range on the album.

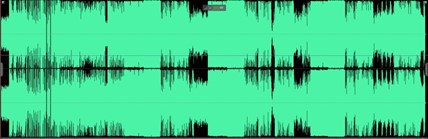

Fig. 2. The dynamic range of the track ‘Black Skinhead,’ from Kanye West’s 2013 album Yeezus, produced by Rick Rubin. Notice the compression and distortion present throughout the track. Source for image: Reddit.com

“Compression” is also a term that audiophiles frequently use in the “loudness war” debate. It has long been a part of the recording process, but it has been abused frequently in recent times. Compression makes quiet passages louder. This is done by narrowing the audio’s dynamic range, thus “compressing” it. There are devices known as “compressors” that are used in recording studios that achieve this effect. It is present in most modern sound recordings, and in modern times it has been greatly misused (thus resulting in the “loudness war” that is so prevalent in modern recordings).

Another crucial term that is frequently mentioned in the “loudness war” discussion is “clipping.” Mark Harris, a producer and audio engineer who has been active since the mid-1980s, described clipping recently in an article:

There is a limit to the amount of power supplying the amplifier inside the speaker – if the requirements go beyond this then the amplifier will clip the input signal. In this circumstance, instead of a smooth sine wave being produced for normal audio, a square waveform (clipped) will be outputted by the amplifier resulting in sound distortion.

In other words, clipping leads to distortion in sound recordings. Notice in the example above the number of square waveforms that appear in the graph. Kanye West’s Yeezus album contains massive amounts of clipping, with the track ‘Black Skinhead’ being one of the many casualties.

There are many theories as to why this occurs. Perhaps the most common theory (and likely the most plausible) is that recordings are mastered loudly (and without dynamics) in order to be the loudest and most noticeable of all. It is a competition to see which recording is the loudest and thus which recording grabs your attention and holds onto it. Record companies have been playing this game since the release of Morning Glory. It is one of the major factors that allows the “loudness war” to continue into the present day.

As was earlier mentioned, loudness grabs your attention. Compression is used at locations such as shopping malls in order for music that is being played quietly to be audible. This is a possible explanation for why record companies use the loudness war as a selling point – that is, the notion that louder recordings equal more sales. For example, Donald Fagen, best known as the frontman of the jazz rock group Steely Dan, released an album that was impeccably mastered last year. Entitled Sunken Condos, the record entered the Billboard 200 album chart at #12 during the week of October 20. During this time, the #1 album on the chart was Mumford & Sons’ Babel album (Bonner). Babel suffered massive issues from a sonic standpoint, with compression being audible at numerous points throughout the album (“Mumford & Sons”). This further adds to the notion that loudness sells records, and that dynamic range is no longer a selling point.

An example of another recent recording that is mastered brilliantly is Jack White’s debut solo album Blunderbuss. Blunderbuss was a critical and commercial success, reaching #1 on the Billboard 200 album chart and earning high reviews from publications such as Rolling Stone and Entertainment Weekly. When asked about why he wanted to do an album without squashing the dynamic range, White replied:

I read this book, Perfecting Sound Forever [by Greg Milner], and it was very interesting, talking about the loudness wars and the speed wars back then—33 versus 45 [rpm]—and how history has gone through all this bizarreness of trying to get the best-quality sound. So this album came up, and I was like, ‘Can we just not change the dynamics of the song? Just make it louder, but don’t compress or limit it?’ Bob Ludwig was like, ‘Of course we can do that.’ And I was like, ‘Why the hell didn’t anyone tell me that you can do that?! I’ve been asking this question for years!’” So the master came back, and it sounded great. There’s nothing squashed or lost in the dynamics, and it still sounded really loud. (qtd. in Gordon 5)

White was looking to make an album that was still loud and powerful, but contained plenty of dynamic range, contrasting him from many of his contemporaries.

Fig. 3. Jack White’s 2012 album Blunderbuss (left) is an example of a modern recording that is mastered properly, whereas Metallica’s 2008 album Death Magnetic has been hailed by some as one of the poorest sounding albums of all-time. Source for images: Amazon.com.

What Do Musicians Think?

Many artists who have had long recording careers are guilty of releasing albums that are “casualties of the loudness war.” David Bowie, Bob Dylan, Jeff Beck, and Eric Clapton have all released recordings in the past decade that lack dynamic range. Another group that has done this is the English alternative band Depeche Mode, whose last album, Delta Machine has been criticized for its harsh sound.

One of the group’s former members, Alan Wilder, has actively spoken out against the loudness war. Wilder, who was in the band from its inception in 1980 until his departure in 1996, has been critical of the sound of modern recordings. “The effect of excessive compression is to obscure sonic detail and rob music of its emotional power leaving listeners strangely unmoved,” Wilder wrote in a January 2008 article he authored for Recoil magazine. “Our sophisticated human brains have evolved to pay particular attention to any loud noise, so initially, compressed sounds seem more exciting. It is short lived. After a few minutes, research shows, constant volume grows tiresome and fatiguing” (Wilder). Wilder states that the loudness contained in recordings is not a pleasant experience, but rather a tiring and “fatiguing” one.

Steven Wilson, a musician who has fronted the progressive rock band Porcupine Tree since 1987, has also stated he is not interested in being a casualty of the “loudness war.” In a 2011 press conference, Wilson stated that “music is art, and it should be presented as such.” He later added, the “quality of music can be much higher than the way people are now experiencing it” (Wilson). Wilson is stating that making recordings louder is not necessarily the best way to listen to them.

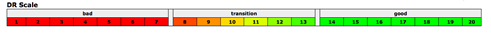

Using the Dynamic Range (DR) Database

A helpful tool in understanding the loudness war is the Dynamic Range (abbreviated DR) Database. This tool analyzes recordings on a “bad – transition – good” scale. It uses a color-coded and number-based system that makes it easy to understand and determine which recordings sound good and which recordings are casualties of the “loudness war.” This is a simple yet accurate way to determine what sound recordings reach a high level of quality and which recordings are severely lacking sonically.

Fig. 4. The DR Scale that is used on the Dynamic Range Database to grade the sound quality on recordings. Source: Dynamic Range Database.

Conclusion

The loudness war has become a major problem in the modern recording industry. Whereas such an issue was nonexistent as recently as twenty-five years ago, it has now emerged as the primary recording technique. It is a practice that should be and needs to be broken, as there are many great recordings that are being issued that lack dynamic range. While Metallica’s Death Magnetic and Kanye West’s Yeezus albums are fine examples of botched mastering jobs (both courtesy of Rick Rubin), other albums such as Sunken Condos by Donald Fagen and Blunderbuss by Jack White remind us that quality sound recordings still do exist. These albums certainly give hope that the future of sound recordings is bright; however, like most issues, it takes an army to accomplish, and that is what must be done here. There must be an “army” of producers, musicians, engineers, record company executives, and, most importantly, record buyers, that are willing to demand audio quality over loudness at all costs. That is truly the way to win the “loudness war.”

Works Cited

“The 500 Greatest Albums of All-Time: 378. Oasis – What’s the Story Morning Glory?” Rolling Stone. Nov 2003. Web. 20 Nov. 2013.

Bonner, Gerard. “Billboard Charts-Oct. 20, 2012.” BonnerfideRadio.com. 11 Oct.Web. 18 Nov. 2013.

Calbi, Greg, dir. Mastering Engineer Greg Calbi on Compression and the Loudness War in Mastering. 25 Aug. 2010. ArtistsHouse Music. YouTube. Web. 14 Nov. 2013.

“Dynamic Range.” Electronics Glossary. Whatis.com. Sept. 2005. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

Giles, Jeff. “30 Years Ago: The First Compact Disc Released.” UltimateClassicRock. 1 Oct 1982. Web. 21 Nov, 2013.

Gordon, Kylee. “Jack White.” Electronic Musician. 17 Jul 2012: 4-5. Web. 21 Nov. 2013.

Hall, Russell. “Lars Ulrich Defends Sound Quality of Metallica’s Death Magnetic.” Gibson.com. 01 Oct 2008. Web. 17 Nov. 2013.

Harris, Mark. “Audio Clipping Definition: What is Audio Clipping?” About.com.page. Web. 21 Nov. 2013.

Mugan, Chris. “Rock Bottom: Poor Sales Devalue Music’s Number 1 Spot.” The Independent. 17 Aug. 2012. Web. 21 Nov. 2013.

“Mumford & Sons – Babel.” Dynamic Range Database. Web. 20 Nov. 2013. “Nirvana.” Dynamic Range Database. Web. 3 July 2014.

Shepherd, Ian. “Dynamic Range Day 2011 – Join us on March 25th – NO MORE Loudness War!” Production Advice. Dynamic Range Day 2013, 18 Feb 2011. Web. 17 Nov. 2013.

Wilder, Alan. “‘Music For The Masses – I Think Not’.” Side-Line Music Magazine. Side-Line. 29 Feb. 2008. Web. 16 Nov. 2013.

Wilson, Steven, perf. I’m not Creating Content for an iPod. 2011. Film. 23 Nov. 2013.