Käthe Kollwitz: Artist and Advocate

The KPD had an important choice to make when it came to the artist that would help them to promote their 1923 anti-Paragraph 218 campaign. The campaign was more than about providing abortion rights to working-class women; it was also an opportunity to change the image of the party in the eyes of the public and to influence voters. The artist chosen for this campaign mattered, and Kollwitz was the ideal recipient of this commission. In order to understand why this was the case, it is crucial to examine Kollwitz’s art, politics, and public image in the years leading up to 1923.

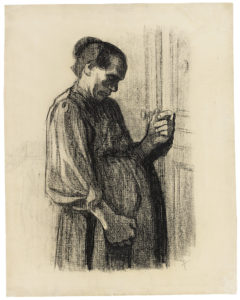

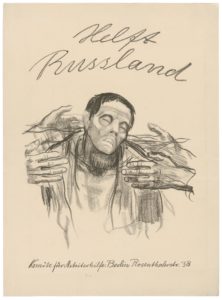

Figure 3. Käthe Kollwitz, Poster for the German Cottage Industry Exhibition in Berlin, 1906, crayon and brush lithography, Cologne Kollwitz Collection, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

Kollwitz was committed to improving the plight of the working class, based on her family’s progressive values and her experiences with the poor workers who were patients in her husband’s medical practice. Indeed, Kollwitz altered her subject matter and medium to more closely express her progressive values. In a retrospective journal entry, she wrote that she felt compelled to depict the “fate of the proletariat” and owed it to them to continue with her artistic studies after her marriage, despite her duties as a wife and mother.[1] As her focus shifted to more politically engaged subject matter, moreover, Kollwitz rejected oil painting, which she felt was a bourgeois medium concerned with pictorial beauty and illusionism. In a 1941 letter describing her formative years as an art student, she wrote, “But in the painting class I made no progress. My fellow students […] had a much better feeling for color than I had. Color was my stumbling block. Then by chance I read Max Klinger’s brochure Painting and Drawing. I suddenly saw that I was not a painter at all.”[2] During the 1890s, Kollwitz began to experiment with different processes of printmaking, such as etching and lithography, which were more suited to her desire to commit her art to political purposes.

Klinger’s treatise was part of a greater resurgence in German printmaking in the 1880s and 90s. Germany was famed for its long history of printmaking, especially woodcuts, as exemplified by the career of Albrecht Dürer; thus, the nineteenth century revival was interpreted through a nationalistic lens. In Painting and Drawing, Klinger discussed the artistic value of the monochromatic drawing by comparing it to oil painting with color. For Klinger, oil painting was bound to depicting the natural world through means of illusionism. By contrast, graphic art could depict the unidealized world and serve as a critical tool to express ideas.[3] Kollwitz embraced Klinger’s argument for the purpose of graphic art prints, especially their ability to express support for social issues through economy of form. Kollwitz marked this shift in her career in a 1922 diary entry: “Actually, my art is not pure art in the sense of [Karl] Schmidt-Rottluff’s. But still, it is art. Each works as he can. I am in agreement, that my art has purpose. I want to have an effect on this era, in which human beings are so much at a loss and so in need of help.”[4] This diary entry indicates how Kollwitz tried to situate herself as an artist concerned with social issues and, in turn, denotes how she considered printmaking as a means to address a wider public.

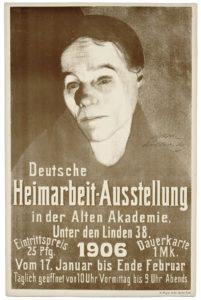

Figure 4. Käthe Kollwitz, Vienna is dying! Save its Children!, 1920, crayon lithograph in up to two colours (transfer, text on ribbed laid paper), Kn 148 II, Cologne Kollwitz Collection, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

Printmaking lent itself to political posters not only aesthetically and ideologically, but also logistically: the reproducibility of lithographs provided a means for artists and political groups to easily distribute their works to a wide public audience. The majority of Kollwitz’s political posters were created between 1919-1926, during the peak of her fame. However, Kollwitz first ventured into the creation of political posters in the early twentieth century, before the formation of the Weimar Republic. In 1906, during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm, Kollwitz was commissioned to create a poster for the Deutsche Heimarbeit-Ausstellung (German Cottage Industry Exhibition; Figure 3), an event that was organized by trade unions and activists to spotlight the treatment of home workers.[5] The exhibition took place on a well-traveled street frequented by the wealthy residents of the neighborhood. Kollwitz’s poster interrupted their leisurely strolls with a message that promoted the interests of the working class: it depicts a working-class woman with her features brightly illuminated, emphasizing her exhausted and unsmiling face. The 1906 poster specifically reprised the popular imperial imagery of the Kaiserin Augusta Victoria, who was often depicted as the caring mother of the nation.[6] With this poster, Kollwitz rejected the Kaiserin’s self-fashioned identity as national matriarch and replaced her with the working-class woman, and targeted this critique of Germany’s class structure at the country’s elites. This project represented an important moment in Kollwitz’s career, as it marked the moment when she shifted to depicting modern subject matter.[7] Unlike her previous works like Peasant’s War or Weaver’s Revolt, which depicted imagined scenes inspired by historical events, these early posters were inspired by modern life in Berlin and advocated for immediate action.

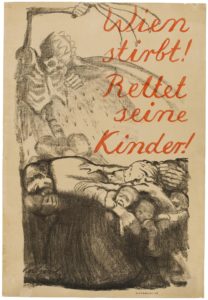

Figure 5. Käthe Kollwitz, Help Russia, 1921, crayon lithograph, Cologne Kollwitz Collection, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

On the basis of her work as a graphic artist and printmaker, Kollwitz was appointed to the Prussian Academy of the Arts in 1919, after the end of first World War and the formation of the Weimar Republic a year prior. With this new recognition, Kollwitz received increasing numbers of commissions for political posters, especially ones that addressed the hardships endured in the aftermath of the war. The first of these post-war commissions was the 1920 poster Wien stirbt! Rette seine Kinder! (Vienna is dying! Save its Children!; Figure 4). For Kollwitz, this poster was the first of many urging for post-war aid for citizens of other countries, including Russia and Austria. Vienna is dying! Save its Children! depicts the allegorical figure of Death, in the form of a crowned skeleton, wielding a whip that represents starvation.[8] Opposite Death, in bright red letters, is the phrase Vienna is dying! Save its Children!. The text, along with the figure of Death, dominates half of the poster and draws the viewer’s eye to the oppressed group below. Kollwitz’s placement of this assertive, imperative phrase demonstrates her skill in manipulating the relationship of text and image to maximum expressive effect. The gargantuan figure towers over a group of children and mothers as the children are clawing at and latching onto the mother. She is stooped forward, clutching a dead infant to her body; two children in the foreground attempt to eat the mother’s arm as she struggles to shield them from Death. This disturbing image effectively foregrounds the suffering of working-class women and their families, a subject to which she would return with her work for the KPD.

The KPD were most likely aware of Kollwitz’s experience creating post-war aid posters when they commissioned her to create one for them. The party’s first partnership with Kollwitz came in 1921, with a project similar to the one discussed above: its aim was to raise awareness about a famine then plaguing Russia due to the post-revolutionary Civil War of 1918-21.[9] This commission, Hilfe Russland (Help Russia; Figure 5), depicts a starving man in a state of extreme vulnerability. His facial features are extremely gaunt and skeletal-like; his eyes are closed, but his mouth is gaping. On either side of the emaciated figure are two pairs of disembodied hands that appear to be in motion, as if reaching out to support him. Above the man’s head are the simple, assertive words “Help Russia.” In her diary, Kollwitz wrote about this commission, noting that that the communists had contacted her to collaborate on a poster, and that she had agreed to help, though she also indicated her reluctance to enter what she referred to as “the political sphere.”[10]

- Figure 6. Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child, 1903, line etching, drypoint, sandpaper and soft ground with imprint of ribbed laid paper and Ziegler’s transfer paper, Kn 81 VIII. Cologne Kollwitz Collection, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

- Figure 7. Käthe Kollwitz, At the Doctor’s, sheet 3 of the series Images of Misery, 1908-1909, black crayon on Ingres paper, NT 475, Cologne Kollwitz Collection, Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

Nevertheless, when the KPD returned to Kollwitz in 1923 with an offer to make a poster on the issue of abortion, she agreed to re-enter the “political sphere.” Kollwitz’s images of mothers and children must have been foremost in the minds of the women’s office members when extending this offer to her. As we already have seen, Kollwitz often depicted maternal figures in both her political and apolitical imagery. Her previous treatment of this motif varied greatly in emotional range, from somber and macabre scenes to joyful, intimate ones. One well-known example that depicts the tragic realities of motherhood is Woman with Dead Child (1903; Figure 6). This stark etching depicts a mother hunched over, cradling her dead child in her lap. In the final version, the mother’s face blends into the child’s neck as his head tilts upwards, connecting her grief to the child’s physical suffering.

Figure 8. Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919-1920, photomontage and collage with watercolor, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie

The KPD committee members may also have known of images in which Kollwitz advocated for abortion access for working-class women. In 1908, Kollwitz produced Images of Misery, a cycle of prints for the journal Simplicissimus, a satirical weekly magazine that covered political and cultural issues. The series as a whole addressed the plight of the proletariat through images of common problems such as homelessness and unemployment. At the Doctor’s (Figure 7) focused on an issue of particular concern for women: unwanted pregnancies, which often created economic hardship for working-class families. The print depicts a heavily pregnant woman knocking on the door to a doctor’s office. Her advanced stage of pregnancy indicates that woman is attending an appointment for prenatal care.[11] Her large, muscular hands associate her with the sort of manual labor that working-class women typically performed. At the Doctor’s reminds viewers that lack of access to birth control or safe abortions weighed most heavily on proletarian women.

Kollwitz was also at the height of her renown as an artist when the KPD selected her for this commission. She was so recognizable that Dada artist Hannah Höch made her face central to her large-scale photomontage Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919; Figure 8). Kollwitz’s visage, clipped from a newspaper, appears in the center of the photomontage, floating above the headless body of the famous dancer Niddy Impekoven.[12] The 1923 campaign was the KPD’s first large-scale action focused on women voters, so they needed to select an artist who could make powerful impact. Partnering with one of the most famous artists of the time gave the KPD’s campaign a sense of credibility. Some members of the public would have recognized Kollwitz’s name when coming across the distributed poster and the events it advertised. This was important, especially given the underlying motivation behind the campaign, which was to reach more women voters and gain their political support.

[1] Käthe Kollwitz, “In Retrospect, 1941” in The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz, ed. Hans Kollwitz, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988), 43.

[2] Kollwitz, “In Retrospect, 1941,” 40.

[3] Prelinger, “Kollwitz Reconsidered,” 15-16.

[4] Prelinger, “Kollwitz Reconsidered,” 79.

[5] Alessandra Comini, “Kollwitz in Context,” in Käthe Kollwitz, ed. Elizabeth Prelinger (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 106.

[6] Comini, “Kollwitz in Context,” 108

[7] Comini, “Kollwitz in Context,” 108.

[8] Kathe Kollwitz, Die Tagebiicher, ed. Jutta Bohnke-Kollwitz (Münich, 2012), 449.

[9] Kollwitz, Die Tagebiicher, 508.

[10] Kollwitz, Die Tagebiicher, 508.

[11] Gisela Schirmer, Käthe Kollwitz und die Kunst ihrer Zeit: Positionen zur Geburtenpolitik (Weimar: VDG, Verl. Und Datenbank für Geisteswiss, 1998), 100-101.

[12] Susan Funkenstein, “Dance Like It’s 1919: Hannah Höch’s Not So Liberated Dancers of the Early Weimar Republic,” in Marking Modern Movement: Dance and Gender in the Visual Imagery of the Weimar Republic (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020), 24.