Politics, Gender, and the Abortion Debate

Much was at stake for the KPD in the summer of 1923; to understand the motives behind the party’s anti-Paragraph 218 campaign and their choice of Kollwitz, we must examine the socio-historical context of the abortion debates. The conversation about abortion in Germany related directly to women’s increased social influence and political power (Figure 9). During World War I, women joined the workforce in greater number as most men went off to fight; many of those women retained employment within the public sphere once the war was over.[1] Then, as a result of the formation of the Weimar Republic, women gained the right to vote. Now that the voting population had increased by half, the KPD and other political parties had to cater to a whole new demographic. For the KPD, this was a demographic with whom they had consistently performed poorly, despite claiming to be the most progressive party for women’s issues. Indeed, political parties on both sides of the ideological spectrum recognized that the issue of abortion presented an opportunity to convert women voters.

During the Weimar era, the KPD’s gender politics were contradictory, reflecting broader anxieties surrounding women’s changing roles in society. The KPD fielded the highest number of women legislators among all of Germany’s political parties at the time. In addition to advocating for the right to an abortion, the KPD introduced legislative proposals and public declarations demanding for equal pay and social protection for women.[2] However, the party consistently belittled women as passive victims of capitalism who were oppressed by low wages and harsh working conditions, while characterizing male laborers as skilled makers.[3] In 1920, the KPD’s “Guidelines for the Communist Women’s Movement” placed contradictory restrictions on women’s organizing and ordered a separation between the bourgeois and proletarian women’s movement. [4] In taking this action, the KPD subordinated women’s issues to their primary focus: the general class struggle. Perhaps because of this mixed record, the KPD struggled to garner significant female support and the KPD remained a predominately male party. In 1929, at the party’s highest point of women’s involvement, their membership levels only reached 17%, while women’s membership in the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and more conservative parties such as the Catholic Center Party, soared.[5]

In 1922, the KPD began an initiative to gain more female support with a party-wide policy encouraging activism on the issue of abortion, then at the center of public debate.[6] Officially outlawed in the mid-nineteenth century, abortion continued to be illegal in Germany under Paragraph 218 of the Weimar criminal code, which required criminal punishment for both patient and doctor, although sentences could range in severity. During the early twentieth century, the Weimar government defended this measure in response to the loss of life after the first World War and the dwindling birth rates being felt across the country. According to Ingrid Sharp, approximately 2 million men were killed in the war and 2.7 million were disabled, which directly impacted the population of the Weimar Republic.[7] However, as perceptions about women changed and they gained political, social, and economic power, Paragraph 218 proved increasingly unpopular.

Figure 10. Women from the Red Front Fighters’ Union of the KPD demonstrate against the ban on abortion, 1928

The political left, including both the KPD and the SPD, saw that abortion reform was a fundamental issue for working-class people, framing it as a tool to oppress women too poor to afford contraceptives. The KPD also emphasized that working-class women were prosecuted for the crime of abortion at a disproportionately higher rate compared to bourgeois women who sought out the same medical procedure. Throughout the 1920s and 30s, the KPD proposed motions to legalize abortion in parliament, held rallies and demonstrations, and launched campaigns to garner public support (Figure 10). Although the SPD worked concurrently on these same issues, scholars have ascribed the KPD greater impact on the abortion debates.[8]

Various social reform groups organized early grassroots protests against Paragraph 218, galvanizing those who opposed the law and led to intervention by larger political groups.[9] The first group to call for an end to Paragraph 218 was the Bund für Mütterschutz und Sexualreform (League for the Protection of Mothers and Sexual Reform), also known as the BfM, which was founded in 1905.[10] Led by prominent feminist Helene Stöcker, the BfM connected the issue of abortion with women’s bodily autonomy and also offered counseling for young and unmarried women.[11] The BfM was in contact with leftist groups such as the KPD, SPD, and the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD); each group took notice of the BfM’s successful grassroots efforts and began to introduce efforts to mobilize their membership.

While the left viewed the issue of abortion and sex reform as a matter of welfare and class equality (Figure 11), the center-right coalition government and ultra-conservative fringe groups framed it as a matter of morality.[12] As with the left, the right’s stance on this issue, which became part of their larger fight against sexual immorality and preservation of the patriarchal family, became central to their platforms. While the KPD and SPD worked to introduce legislation that would reform Paragraph 218, the Center Party and the German National People’s Party (DNVP) actively opposed them.[13] Both parties garnered political and financial support from the conservative population and were backed by the Catholic and Protestant Churches.[14] Parties on the right, with the support of the German Medical Association (DÄVB), condemned early motions to legalize abortion on the grounds of politics, medicine, and morality. The conservative parties actively campaigned the Reichstag, the Weimar legislature, to reject the proposed amendments to Paragraph 218 and maintained that abortion, unless under severe and strict medical situations, should remain illegal and punishable with a prison sentence. In 1925, the DÄVB dedicated their entire annual conference to the issue of abortion.[15]

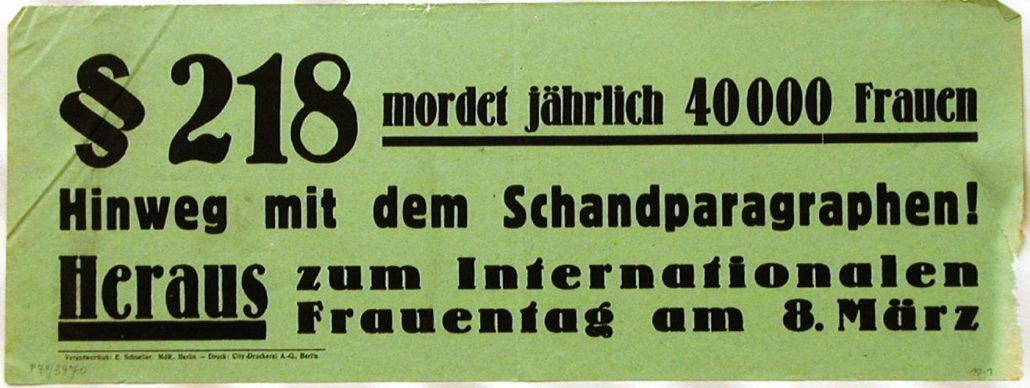

Figure 11. Poster for Women’s Day, “Paragraph 218 kills 40,000 women every year. Down with this disgraceful paragraph!”, 1924/1933 © DHM

Despite the right’s efforts to beat back this issue, in 1926 the Reichstag passed the most significant abortion reform amendment up to that point; this measure redefined abortion, making it a misdemeanor rather than a crime.[16] The amendment was based on a 1922 proposal that had been drafted by the Minister of Justice and SPD party member Gustav Radbruch, and was supported by the left and center-left parties.[17] The motion was rejected by the Centre Party and DNVP on the grounds of morality and declining population, respectively; however, the motion passed with 213 votes to 173.[18] Women were no longer threatened with serious prison sentences and abortions were no longer considered homicides.[19] While the amendment was a far cry from the complete legalization that the KPD wanted, the reform represented a significant moment in the abortion debate and sex reform as a whole.

These abortion debates and their relationship to the women’s vote were determinative in the KPD’s decision to commission a poster from Kollwitz. For the KPD, the abortion debate was both an important working-class issue and an opportunity to garner more support among newly enfranchised women. Given their poor standing with women voters, there was much at stake. Not only were working-class women in desperate need for reproductive care, but without the support of women voters, the KPD’s future looked grim.

[1] Ingrid Sharp, “Gender relations in Weimar Berlin,” in Practicing Modernity: Female Creativity in the Weimar Republic, ed. Christiane Schönefeld (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2006), 1-13.

[2] Eric D. Weitz, “The Gendering of German Communism,” in Creating German Communism, 1890-1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 188

[3] Weitz, “The Gendering of German Communism,” 189.

[4] Grossmann, “German Communism and New Women: Dilemmas and Contradictions,” 136.

[5] Weitz, “The Gendering of German Communism,” 189

[6] Usborne, The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany, 159.

[7] Sharp, “Gender Relations in Weimar Berlin,” 2.

[8] Usborne, The Politics of the Body, 156-163. Usborne notes the SPD also contributed immensely to the legalization effort led on the left. She reminds us that many modern-day publications of this moment rely on biased firsthand accounts that “eulogize” the efforts of the KPD while “underestimating” the efforts of the SPD. For the purposes of this project, I will be focusing namely on the efforts of the KPD, given their relationship with Kollwitz and the commissioning of this poster.

[9] Myra Marx Ferree, et. al., eds., Shaping Abortion Discourse: Democracy and the Public Sphere in Germany and the United States (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 26

[10] Marx Ferree, Shaping Abortion Discourse, 26

[11] Grossmann, Reforming Sex, 17.

[12] Usborne, The Politics of the Body, 70.

[13] Helen Boak, Women in the Weimar Republic, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), 212-213.

[14] Boak, Women in the Weimar Republic, 212.

[15] Usborne, The Politics of the Body, 183.

[16] Boak, Women in the Weimar Republic, 212-213.

[17] Usborne, The Politics of the Body, 170.

[18] Usborne, The Politics of the Body, 173.

[19] Usborne, The Politics of the Body, 174.; The abortion debate continued into the 1930’s as the left pushed further for the legalization of abortion. This included even more campaigns from the KPD and other works of art commissioned by women artists. Alice Lex-Nerlinger and Hanna Nagel both produced images in support of these campaigns. Both artists used maternal proletarian imagery but in a different way to Kollwitz, keeping in mind that they were a generation younger than the acclaimed artist. For the purposes of this project, I am discussing the abortion debate up to the point of the involvement of Down with the Abortion Paragraphs. To read more about the works by Lex-Nerlinger and Nagel see: Marsha Meskimmon, “The Mother” in We Weren’t Modern Enough: Women Artists and the Limits of German Modernism, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 75-112.