Women, Popular Media, and the KPD in Weimar Germany

As the abortion debate raged in the early 1920s, the KPD also took part in a related battle: that of representations of women in mass media. The KPD struggled to keep up with the shift in Weimar popular media that began to reflect the changing role of women in the public sphere. They were reluctant to align themselves with the stereotype of the New Woman, a figure whose close connection to capitalist mass consumerism made her anathema to the party’s ideals. However, it was paramount to the future of the party that they respond to the new attention paid to women in Weimar society, and the way this figure was visualized. It is therefore important to analyze the KPD’s campaign materials in relation to the proliferating images of New Women in Weimar visual culture.

It is important to note that the “New Woman” was not a real person, but an image and stereotype propagated by popular mass media. This complex, contradictory figure served as a site of contestation through which competing visions of modern German society were debated. Many progressive feminists viewed this figure positively, as the embodiment of women’s political enfranchisement, economic independence, and growing equality with men.[1] For some on the political left, the New Woman symbolized the evils of capitalism; conservatives, by contrast, considered the New Woman a threat to the German family, given her association with a breakdown of traditional gender divides. But for all of these groups, the New Woman symbolized modernity, and therefore required some sort of response.

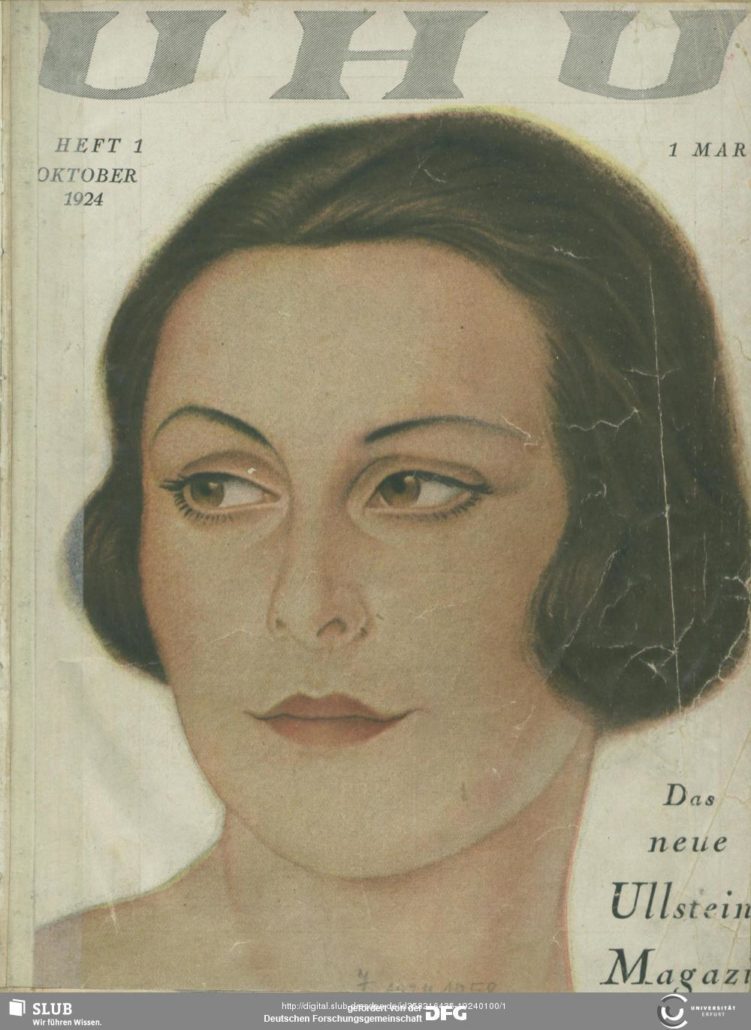

This widespread preoccupation with the New Woman was due in part to the ubiquity of this figure in Weimar culture and the mass media, from films to novels and, above all, illustrated magazines (Figure 12).[2] Illustrated magazines first appeared in Germany in the late nineteenth century, but expanded dramatically during and after World War I.[3] Their popularity was driven in part by the inventive integration of photographs into the layout, as well as by photojournalism, which surged in use as a way to relay information during the war. Magazines used photojournalistic spreads to create visual essays that covered issues ranging from the arts, travel, profiles of celebrities, and social concerns.[4] The integration of photographs in popular media was also used to create the advertisements that filled the pages of illustrated magazines such as the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ), a major weekly magazine published by the Ullstein company that was founded in the 1890s.[5] Images of models, actresses, and female politicians alike dominated the covers of magazines, representing the shift in the new role women played within the public sphere and delivering messages of female empowerment. It is important to note, however, that these idealized images purveyed by magazines were targeted towards bourgeois women with the means to purchase illustrated magazines and the products that they advertised.[6]

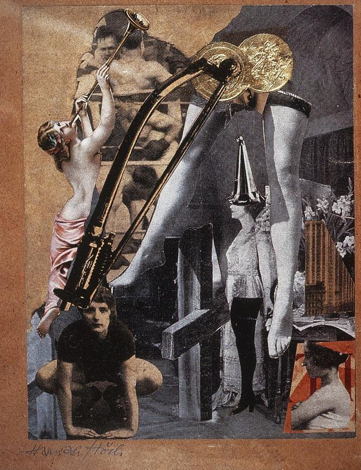

The New Woman played a central role in art of the Weimar period as well—especially in the photomontages made by members of the Berlin Dada group. The emergence of Dada photomontage was directly linked to the explosion of illustrated popular media during this time. Hannah Höch in particular integrated images of the New Woman from mass media into her photomontages, seemingly both to celebrate women’s newfound power and to critique this as well as other stereotypes that inhibited women’s freedom.[7] Höch’s 1920 photomontage Dada-Ernst (Figure 13), for example, features a crouching gymnast with the short, bobbed hair that functioned as the New Woman’s chief attribute. The composition is filled with other emblems of modern life, such as a skyscraper and pair of boxers. Above the gymnast’s head is a piece of metal machinery that forms a diagonal line leading the eye towards a pair of gold coins above two disembodied female legs. In between the legs is a woman dressed in a long ballgown, with the silhouette of another leg imposed over her lower half. As Maud Lavin notes, in Dada-Ernst we see Höch “cataloguing and recombining of signs of modernism,” including the New Woman, as a way to both picture and interrogate modern society.[8] Above all, like so many of Höch’s artworks, Dada-Ernst puts the New Woman, and the role of women in popular media, at center stage.

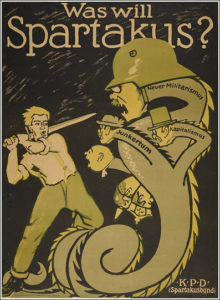

While Dada art and the mainstream illustrated press abounded in images of the New Woman, the KPD’s publicity strategies hinged upon the male laborer. Though the KPD was founded in part by women such as Rosa Luxemburg, and women comprised some of its leadership, the party’s political posters almost invariably portrayed their culture through images of idealized, militarized male figures. Their aim was to differentiate the party from other leftist organizations: using images of construction workers, lathe operators, riggers, and coal miners in their publications, the KPD wished to associate themselves with a “manly resolve” that, by implication, their rival parties lacked.[9] For example, in a 1919 poster produced by the Spartacist League, the forerunner to the KPD (Figure 14), a working-class man wields a sword as he faces a Lernaean Hydra. Each of the Hydra’s snarling heads represents one of the forces the party aimed to fight, including capitalism, new militarism, and the Junkers (the landed nobility). Spartacus has already conquered one head, which wears a pickelhaube, a spiked military helmet associated with the Prussian army and represents the imperial reign of Kaiser Wilhelm. By placing the sword in the hand of Spartacus, the working-class man, the KPD credited him with the destruction of imperial rule. Above the figure is emblazoned the question Was will Spartakus? (What does Spartacus want?); the answer to the question, it would seem, is communism and the KPD. This question addressed the male voter directly and encouraged sympathetic viewers to identify with the accompanying male figure, ignoring female viewers entirely. Similarly, in a 1924 election poster designed by Rudolf Schlichter (Figure 15), the working-class man is front and center. Holding a torch above his head that represents the flame of revolution, he leads a crowd of other working-class men as he urges the viewer to vote for the KPD in the upcoming election. Notably, we see no women in that crowd—an indication that the party still conceptualized its primary audience as working-class men.

- Figure 14. What Does Spartacus Want?, 1919

- Figure 15. Rudolf Schlichter, KPD Election Poster, 1924, © Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (HLMD)

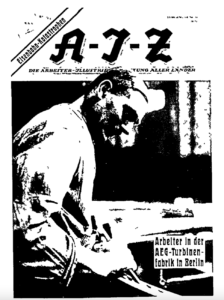

- Figure 16. AIZ magazine cover, AIZ 34 (1928)

- Figure 17. AIZ magazine cover, AIZ, January 1928

Figure 18. Campaign poster of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) for the National Assembly elections, Berlin 1919 © Deutsches Historisches Museum

Images that glorified male laborer were abundant in the pages of the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (AIZ), an illustrated weekly magazine affiliated with multiple German communist parties, including the KPD. An AIZ cover from 1928 (Figure 16), for example, depicts a male laborer concentrating on his work in a turbine factory in Berlin. This industrial setting, specified in the caption, reveals the extent to which German communism held factory workers in high esteem. An additional magazine cover (Figure 17) depicts an industrial lathe operator hard at work, accompanied by the phrase “Wenn Dein starker Arm es will…” (“When your strong arm wants it…”), a lyric from a popular anthem of the German worker’s movement. In both cases, the glorified male laborer is used as a figurehead for the working class.

Meanwhile, the KPD’s rival leftist party, the SPD, made women far more central to their media campaigns. We see this in a 1919 campaign poster (Figure 18) for the National Assembly elections that features a working-class man and woman standing side by side. The woman’s pose evokes the allegorical figure of Liberty in Eugène Delacroix’s famous painting Liberty Leading the People (1831): with one hand defiantly planted on her hip, the other waves an enormous red flag. The text of the poster addresses women directly, calling out to “Frauen” in the upper left corner of the image. The caption below the figures, which reads “Equal rights—Equal responsibilities; Choose the Social Democrats,” suggests that the SPD’s policies prioritize the concerns of women. The woman depicted in the poster is clearly meant to represent a version of the New Woman. While she is dressed in a modest skirt and blouse, she sports a cropped hairstyle and wears high-heeled shoes. This figure seems to be a hybrid of the fashionable New Woman and the more traditional working-class woman. Kollwitz would take a very different approach to depicting the working-class woman in her poster for the KPD.

[1] Sharp, “Riding the tiger,” 123.

[2] Marsha Meskimmon, “The Neue Frau: Icons, Myths and Realities,” in We Weren’t Modern Enough: Women Artists and the Limits of German Modernism, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 163-196.

[3] Winifried Lerg, “Media Culture of the Weimar Republic: A Historical Overview,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 12 no. 1 (1988), 96.

[4] Hanno Hardt, “Pictures for the Masses: Photography and the Rise of Popular Magazines in Weimar Germany,” Journal of Communication Inquiry, 13, no. 1 (1989): 7-29.

[5] Lerg, “Media Culture of the Weimar Republic,” 98.

[6] Lavin, Cut with the Kitchen Knife, 4.

[7] Lavin, Cut with the Kitchen Knife, 5.

[8] Lavin, Cut with the Kitchen Knife, 8.

[9] Weitz, Creating German Communism, 191.