Jin Noda 野田仁

Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa

Tokyo University of Foreign Studies

After the Meiji restoration, interactions with foreign countries played an important role in the course of modern Japanese history. As is well known, at the turn of the twentieth century Japan was involved in two major wars in and around the northeastern territory of the Qing Empire: the Sino-Japanese War (1894–5) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5). In the course of these battlefield engagements, the Army General Staff and other members of the Japanese government began to consider the strategic value of territories in northwestern China. More specifically, they began to set their sights on Xinjiang, or East Turkestan. This article will examine the earliest Japanese attempts to explore and infiltrate Xinjiang during the latter half of the nineteenth century and shed light on the first Japanese contacts with Muslim societies.

This study is based upon research carried out in the Central Government Archives of the Republic of Kazakhstan (TsGA RK), which contains some of the records kept by the Russian imperial bureaucracy regarding Japanese agents who explored Xinjiang.1 The perspectives of the Russian archives in Kazakhstan will be supplemented by contemporary publications and archival records produced by Japanese explorers and government agents who traveled to Xinjiang during this time.

Prior research has focused mainly on Japan’s interest in Xinjiang within the context of Tokyo’s policies toward China (Fujita 2000; Fang 2000).2 From a broader perspective, however, Japan’s interest in Xinjiang might be better explained within the context of Russo-Japanese relations. Though the Japan-based Chinese historian Wang Ke (2013, 2015) has drawn some attention to such an approach, there is still much room to consider Japanese explorations from the perspective of Russians and local Muslims. Recently, Terayama (2015) has utilized Soviet archives to study Japanese intelligence activities in Xinjiang during the 1930s, thus enhancing our knowledge of how these activities influenced Soviet views of Xinjiang.

Against a backdrop of acute Russian and British interest in the geopolitical fate of Xinjiang, Tibet, and Russian Turkestan, it is important to consider when, where, and how the Japanese responded to the British and Russian agendas in Central Asia. What did the Japanese think about Xinjiang? In order to answer this question, we must first understand the chief political developments in Xinjiang during the late nineteenth century as well as how the interests of Russia, Britain, the Qing, and local Muslims influenced these developments.

Japan and the “Ili Crisis”

From 1871 to 1881, Russia took advantage of the destabilization of the region brought about by the Yaqub Beg interregnum to occupy the northern regions of Xinjiang, in a development known as the “Ili Crisis” (Noda 2010). What were the implications of the Russian occupation of the Ili region for Japan? The Japanese diplomat Nishi Tokujirō, one of the first Japanese to visit Central Asia, has left a record of a report that he wrote during this time when he passed through the region. In “A Description of Central Asia” (Chū-ajia kiji 中亞細亞記事), Nishi noted “the conflict around Ili” and what he “witnessed regarding military affairs” (Nishi 1886: pt. 4, supplement). The political motivation for his journey to Central Asia can be confirmed by a document within the Japanese Foreign Ministry dated to June 1880, which explains that his journey “was made for exploring local places in light of the negotiation on the region between Russia and the Qing” (Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, hereafter JACAR: A07060589600).3 This is a reference to the discussions then ongoing between St. Petersburg and Beijing on the return of the occupied Ili region. Nishi also mentioned that he intended to further investigate the Qing’s military power in Xinjiang by visiting Jinghe 精河, a town further east of Ili (Nishi 1886: pt. 3, 225).

Japanese interest in the results of the negotiations regarding the Russian return of Ili to the Qing was born out of a concern for how the results of these negotiations might impact Japanese discussions with the Qing on the fate of the Ryukyu islands and Taiwan. Nishi’s report includes an entire section devoted to a “Discussion on Ili.” In hindsight, it is clear that the Japanese government believed that the conflict between the Russian and Qing governments over Ili could exert a positive influence on Japan’s diplomatic negotiations with Beijing regarding the Ryukyus (Yamashiro 2015). On June 27, 1881, in a telegram to Ito Hirobumi and Inoue Kowashi, the Japanese consul at Tianjin Takezoe Shinichiro revealed Tokyo’s intention to exploit the possibility of a Sino-Russian war for its own purposes (JACAR: B03041149800).

Russia was very concerned about the Japanese attitude toward the Qing, and attempted to collect information about Japan’s posture toward Beijing through the Russian legation in Tokyo (Russian State Military History Archive, hereafter RGVIA: f. 451, op. 1, d. 2, l. 11). It was in fact the Russians who had helped to facilitate Nishi’s passage through Ili in the first place. Their eagerness to do so might be explained by the Russian expectation that Japan might side with Russia in the dispute in spite of Tokyo’s avowed policy of neutrality (JACAR: B03041149200).

Nishi’s exploration of northern Xinjiang amid the backdrop of the Ili Crisis represents the earliest Japanese attempt to procure firsthand intelligence regarding Russian political intentions in Central Asia. The second attempt to do so came in 1889, when a local branch of the Rakuzen-dō drugstore active in Hankou dispatched Ura Keiichi 浦敬一 to Xinjiang with the intent of helping local Muslims resist Russian intrusions. Ura, however, never made it to Xinjiang, having lost his way en route (Kuzuu 1933: 382–95).

The First Professional Agents from Japan

It was only two decades later, after the Russo-Japanese war (1904–5), that Tokyo began to adopt a proactive and aggressive strategy for collecting firsthand intelligence regarding Russian designs on Xinjiang. One of the most pressing items on Japan’s agenda was to learn as much as possible about Russia’s plans to construct a railway into Xinjiang.4 The intelligence agents involved in these early operations included Hatano Yōsaku 波多野養作, Hayashide Kenjirō 林出賢次郞, Sakurai Yoshitaka 櫻井好孝, Kusa Masakichi 草政吉, and Miura Minoru 三浦稔, all of who graduated from the East Asia Common Culture Academy (Tōa Dōbun Shoin 東亜同文書院) school in Shanghai, where they trained for careers in business and government service related to China.5

In May 1905, as a Japanese victory in the war against Russia seemed increasingly likely, all five men were dispatched by the Japanese Foreign Ministry to strategically important locales in the northwestern regions of the Qing Empire. As Foreign Minister Komura Jutarō 小村壽太郞 wrote to Minister Uchida Yasuya, the Japanese minister in Beijing, on May 9, “these five figures will be dispatched for the investigation of Russian activities on the periphery of China” (JACAR: B03050330 700). These destinations included Urga, Uliyasutai, and Khobdo in Outer Mongolia (Miura, Kusa, and Sakurai, respectively); the northwestern Qing province of Gansu (Hatano); and the Ili region in Xinjiang (Hayashide). The very next year, the Army General Staff also sent Hino Tsutomu 日野强, a military officer who traveled with an attendant, Uehara Taichi 上原多市, to Xinjiang.6

In his memoir, Hayashide recalled the inspiration for these missions as stemming from the “result of deliberations” between Japanese and British diplomats. “England would dispatch agents from India up to Kashgar in southern Xinjiang,” he later wrote, “while Japan would send agents to Ili, Khobdo, Uliyasutai, and Urga to conduct research on the boundary zones between Outer Mongolia and Xinjiang,” most of which was then under Russian influence (Hayashide 1938: 172–73). The five men sent by the Foreign Ministry were supported by a confidential fund under Minister Komura Jutarō’s oversight.

These Japanese intelligence agents did not go unnoticed by the Russians, who had long kept close tabs on Japanese travelers through Siberia. For instance, when Fukushima Yasumasa 福島安正 made his famous journey through Siberia in 1892, members of the General Staff of the Russian military shadowed him and submitted reports on his activities. Fourteen years later, similar reports were compiled on the movements of Japanese military agents Hirayama Haruhisa 平山治久 and Nagase Hōsuke 長瀬鳳輔, who entered West Siberia in 1906 (Grekov 2000: 75). In China, Japanese travelers were followed not only by Russian military attachés resident in all the major cities, but also by the four Russian consuls stationed in Xinjiang. No matter where the Japanese went, it seemed, the Russians were watching them.

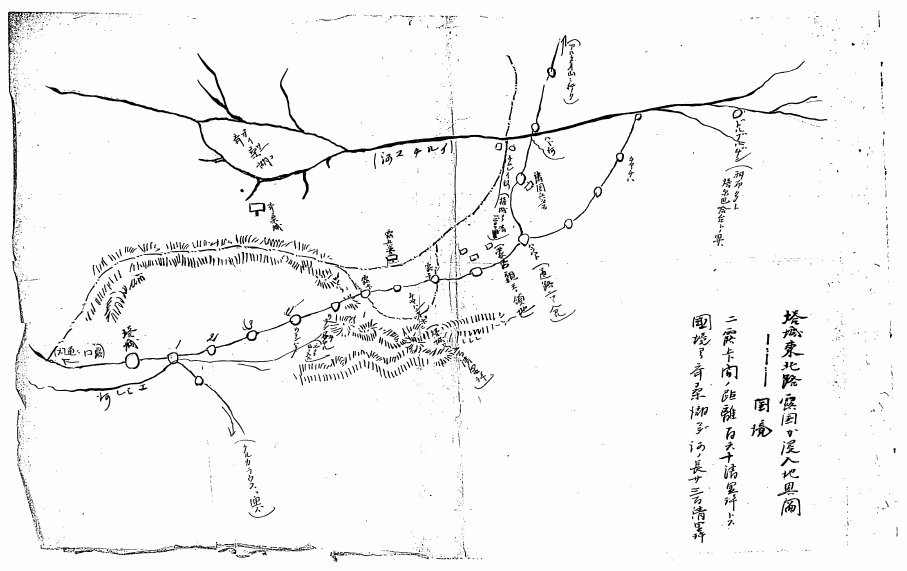

Fig. 1. A map of Tarbagatai (Tacheng) drawn by Hayashide Kenjirō during his travels through northern Xinjiang (JACAR B03050331400).

Russian Reports on Japanese Spies in Xinjiang

During and after the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–5, Russian officials evinced an increasing anxiety regarding Japanese espionage in Xinjiang. For instance, in 1902, when the Buddhist monk and scholar Ōtani Kōzui 大谷光瑞 undertook the first Japanese archaeological expedition to Xinjiang, entering the province via Russian Turkestan, Russian authorities and consuls stationed along his route reported closely on his activities, on the assumption that his expedition was a pretext for espionage (Shirasu 2012: 27). Later, Hatano Yōsaku, after completing his reconnaissance of Gansu, reached Urumchi and reported on Russian surveillance of his movements (JACAR: B03050330800).

The majority of Russian archival documents, however, concern Hayashide Kenjirō, who was sent by the Japanese Foreign Ministry in July 1905 to collect intelligence throughout Xinjiang. From the moment he left Beijing, Hayashide was closely watched by the Russians. On June 6, 1905, a telegram from Leonid Davydov, a member of the governing board of the Russo-Chinese Bank in Beijing, instructed Russian officials to keep an eye on the Japanese “spy” Hayashide, whose ultimate destination of Xinjiang was already known (Osmanov 2005: 410). Just one week later, on June 13, a Russian report from the General Staff office informed the commander of the Turkestan Military District that Hayashide was being sent to Xinjiang for the purpose of organizing a network of spies, distributing Japanese propaganda, and compiling intelligence on Xinjiang [Fig. 1]. On June 20, the military governor of Semirech’e responded to this report by issuing orders to arrest Hayashide upon his arrival in Russian Turkestan (TsGA RK: f. 46, op. 1, d. 116, ll. 48–49).

These telegrams leave little doubt that Russia was intent on eliminating the threat of Japanese espionage in Xinjiang. Other archival documents from this same period—June to September 1905—reveal Russian suspicions regarding purported Japanese officials in Tarbagatai (Tacheng) (RGVIA: f. 661, d. 76, l. 226ob.) and a Japanese military instructor in Urumchi (RGVIA: f. 661, d. 67, l. 248). A few years later, in 1908, the Russian consul in Urumchi submitted a comprehensive report to the headquarters of the Omsk Military District on Hayashide’s journey to Tarbagatai, during which time he was accompanied by Major Hino. This report included details on the extensive photographic activity undertaken by the two men along the Qing-Russian border (RGVIA: f. 2000/c, op. 15, d. 28, l.69–71). The photographic activities of Sakurai Yoshitaka in Khobdo, situated along the northwestern border between Outer Mongolia and Xinjiang, also caught the attention of Russian consuls. According to the Russian consul at Uliyasutai, who met Sakurai, Sakurai tried to pass himself off as a Japanese merchant (RGVIA: f. 2000/c, op. 15, d. 28, l. 13).

The report of Major Hino Tsutomu, one of only two Japanese agents (along with Uehara) to visit southern Xinjiang, has yet to turn up in the Japanese archives.7 There are, however, other sources capable of shedding light on his intelligence activities in Xinjiang, most of them from a Russian perspective. The Finnish military officer Carl Gustav Mannerheim, who accompanied Paul Pelliot’s archaeological expedition to Xinjiang in 1906–8 and gathered intelligence for Russia along the way, made a special effort to track Hino’s movements (Mannergeim 1909: 4).8 Because Hino met S. Fedorov, the Russian consul of Ili who also helped facilitate Mannerheim’s travels through Xinjiang, Mannerheim had little trouble finding Hino. On May 31, 1907, Mannerheim noted the appearance, “just in front of me, of Japanese Major Hino with several Chinese officials, conducting photographic research, [and] advancing via the camp of the [Torghut] Khan” (Mannergeim 1909: 28).

For Mannerheim and the Russians, Hino’s appearance in Xinjiang confirmed the spread of Japanese influence into Xinjiang. As a result, when Mannerheim learned of the pro-Japanese attitude of Changgeng 長庚, the Qing military governor of Ili, he immediately blamed Hino (Mannergeim 1909: 33), who was on good terms with Changgeng (Hino 1973: pt. 1, 185). Mannerheim repeatedly emphasized the spread of the Japanese influence into northwestern China during the years of his expedition, connecting Hino’s activities to the dispatch of Japanese teachers in inner China. In the end, Mannerheim concluded that the Japanese military was increasing its power in the region (Mannergeim 1909: 156–58). The Russian consul in Urumchi offered more specific details on the nature of this power. On October 5, 1908, the consul informed the Russian legation in Beijing that Hino had met and exchanged name cards with Sa‘id Muhammad al-‘Asālī, a Muslim intellectual who had travelled to Xinjiang from British India (RGVIA: f. 2000/c, op. 15, d. 28, l. 104).9 As Russian military officer A. Snesarev (1907) warned, Japan was trying to increase its knowledge of Islam and to make political use of Muslims in Asia.

Japanese intelligence activities were not confined to Xinjiang. In 1908, Hamaomote Matasuke 濱面又助, a military attaché of the Japanese legation in Russia operating under the support of the Army General Staff, traveled to the Bukharan Emirate, then under loose Russian control. Though Hamaomote’s official Japanese report has not yet been found, Russian archives show that his movements, along with those of other Japanese military attachés, were closely monitored throughout Central Asia (RGVIA: f. 2000/c, op. 15, d. 29, l. 96 and 105). Japan also tried to initiate contact with the Dalai Lama in Tibet. Teramoto Enga 寺本婉雅, a priest of Higashi Hongan-ji Temple who was supported by General Fukushima (Esenbel 2018), maintained frequent communications with the Dalai Lama (Teramoto 1974). Teramoto also helped to facilitate a meeting between the Dalai Lama and Hatano Yōsaku, the East Asian Common Culture Academy graduate who had undertaken the mission to Gansu. These efforts prove that the Japanese government, or at least the Army General Staff, maintained a high level of interest in the political fate not only of Xinjiang, Outer Mongolia, and the inner Chinese provinces, but of Tibet as well.

Japanese Intelligence Reports on Xinjiang

After their return from the Qing borderlands, the five Japanese graduates of the East Asian Common Culture Academy submitted detailed reports of their travels to the Foreign Ministry’s Political Affairs Bureau. Printed copies of these reports were also distributed to the Military Ministry as well (JACAR: C03022995500). Of the five reports, those of Kusa Masakichi, Miura Minoru, and Sakurai Yoshitaka are devoted chiefly to the affairs of Outer Mongolia. By contrast, the reports of Hatano Yosaku and Hayashide Kenjiro go into great detail about Xinjiang. While Hatano spent most of his time in Urumchi, Hayashide covered much more ground en route to the northern town of Tarbagatai. As a result, Hayashide’s report contains a greater wealth of detail. The reports of both men, however, offer a fascinating glimpse into Japanese assessments of the Russian presence in Xinjiang.

Both Hayashide and Hatano noted the deep involvement of the Russian consulates in Kashgar, Urumchi, Ili, and Tarbagatai in the collection of intelligence regarding local affairs and the activities of foreign agents in Xinjiang (Hatano 1907: 77–78; Hayashide 1907: 11). Hayashide even went so far as to comment upon “Russia’s management of Xinjiang” (Hayashide 1907: 67). Of particular interest to both men was the role played by the Russian consulates in the cross-border trade of expatriate Muslims from Russian Turkestan (Hatano 1907: 66–67). They made a careful distinction between the Turkic-speaking Muslim subjects of the Qing Empire—known today as Uyghurs but referred to as chantou 纏頭, or “Turban Heads,” by the Chinese of the day—and the non-Slavic Turkic-speaking Muslim subjects of the Russian empire, whom the Japanese reports identified as coming from Tashkent or Andijan (Hayashide 1907: 21, 54). They also noted the presence of Russian Tatars, who were called “Nogai” in Xinjiang.10 Neither Hayashide nor Hatano failed to comment upon the tendency of the Russian consuls to lobby on behalf of Russian Muslims in Xinjiang, often to the detriment of Qing economic interests.

Both reports also made a careful distinction between Chinese-speaking Muslims (Hui or “Tungans”) and Turkic-speaking Muslims. Hatano described the latter as “Turkestan people, who separately belonged to Russia and Qing” (Hatano 1907: 40–41). Nevertheless, Hatano still regarded the Russian Turkic-speaking Muslims as “superior” to the Turkic-speaking Muslim subjects of the Qing. Neither group, however, was seen as acting in concert with the Hui, to whom was ascribed the chief role in the Muslim rebellions of the 1860s.

Hatano and Hayashide also evinced anxiety regarding the extension of Russia’s communications and transportation infrastructure into Xinjiang. For instance, the Russians already operated both a postal and telegram service to several major cities in the province (Hatano 1907: 30–31; Hayashide 1907: 36). As for the railway, Hatano noted a stark contrast in speed of construction: whereas the Russians had already completed a trunk line from Semipalatinsk to Tashkent, Qing plans for a railway from Ili to Lanzhou still existed on paper only. Hayashide worried that Russian railroads would one day dominate Xinjiang (Hayashide 1907: 74).11 As the situation in Manchuria could well attest, the construction of railways in China by foreign powers carried great significance for the development of outside influence in the region.

Based on his travels through Xinjiang, Hayashide proposed that Japan take a proactive approach to countering Russian influence in Xinjiang by offering “protection” for the Qing. “After the Russo-Japanese War, Russian activities [to Xinjiang] completely changed,” he wrote. “If the Japanese are to be a guardian for the Qing, then we should tighten the connection between Xinjiang and Japan” (Hayashide 1907: 71–75).

Attitudes of the Local Muslims

How did the people of Xinjiang view the specter of Japanese influence in their land? According to Hino, a Muslim merchant in Tarbagatai who held Russian nationality welcomed his presence, commented upon the shortcomings of Russia, and praised the prowess of Japan (Hino 1973: pt. 2, 171). The other Japanese explorers also observed favorable attitudes toward Japan, mostly as a result of its victory over Russia in the 1904–5 war (Hatano 1907: 48–50; JACAR: B03050330800; see also Hayashide 1907: 59). By contrast, Mannerheim reported a different impression. “I couldn’t find any sympathy [of the local people] with the Japanese, which I had heard of before my departure, except for the rare case of an obvious Japonophile” (Mannergeim 1909: 12).

Another perspective on Japan can be glimpsed in the writings of Qurbanghali, a Tatar mullah at Tarbaghatai. In his “Histories of the Five Easterns” (Tavārīkh-i khamsa-yi sharqī), published in 1910, Qurbanghali paid much attention to Japan’s swift development after the Meiji restoration (Noda 2016: 50–53). In particular, he noted the goodwill mission of the Ottoman frigate Ertuğrul, which docked in Japan for three months in 1889–90 before its loss at sea—and subsequent Japanese rescue efforts—on its return voyage to Istanbul (Qurbān ‘alī 1910: 700). Though much of his information on Japan was derived from secondary information culled from periodicals published in Russia (such as Terjuman), the fact that such information found its way into educated circles in Xinjiang at all is worthy of note. It seems that the goodwill voyage and wreck of Ertuğrul struck a particular chord with some Muslims in Xinjiang. Hino, too, made note of favorable impressions of Japan in Xinjiang that were tendered in the context of the Ertuğrul mission to Tokyo (Hino 1973: pt. 2, 119).

Conclusion

The intelligence operations conducted by Japanese agents along the non-Han peripheries of the Qing Empire in the first decade of the twentieth century came at a pivotal time in Japan’s expansion onto the Asian mainland. Undertaken in the final months of the Russo-Japanese War and at the same time as the establishment of a “protectorate” over Korea, these missions ushered in some of the first contacts between Japan and the Muslim peoples of Central Asia. The chief organizational sponsors of these operations were the Japanese Foreign Ministry and the Army General Staff.

Despite the fact that most of the lands covered by these missions were still under Qing suzerainty, the reports submitted by Japanese spies leave no doubt that St. Petersburg, not Beijing, weighed most heavily on the minds of Japanese officials. For example, 1912 report, “Russian management of Manchuria-Mongolia and Xinjiang” (Man-mō oyobi shinkyō ni taisuru rokoku no keiei 満蒙及新疆ニ對スル露國ノ經營) proposed further intelligence operations not only for Xinjiang, but for Russian Turkestan as well (JACAR: B03030414500). This proposal was followed six years later in 1918 by the formal establishment of a Japanese intelligence organ devoted to Xinjiang (JACAR: C03022436400; see also Fang 2000; Wang 2015). Later intelligence operations undertaken by Japanese agents in the 1930s are the direct descendants of these early initiatives. As Terayama (2015) has noted, however, Japanese intelligence activities were not successful in evading the watchful eyes of the Russians, whose counterintelligence efforts closely tracked their every move.

One of the most significant results of these missions was the compilation of firsthand reports regarding the Muslim peoples of Central Asia for Japanese officials in Tokyo, who began to express an interest in various pan-Islamic discourses and how such discourses might be utilized to Japan’s advantage. This interest was further stimulated in 1909, when Abdürreşid Ibrahim, described by the above mentioned Nakakuki as “a Tatar patriot,” visited Japan. Ibrahim’s speeches and articles were subsequently published in the journal Japan and the Japanese (Nihon oyobi Nihonjin 日本及日本人) (Komatsu 2018).

One measure of the interest Ibrahim’s visit seems to have stimulated in Japanese policymaking circles can be glimpsed in the research of Nakakuki Nobuchika 中久喜信周, a reporter for the Yangtze River News Agency (Yōsukou tsūshinsha 揚子江通信社) in Hankou. In 1910, Nakakuki, whose article was published in the same journal that printed Ibrahim’s speeches, was commissioned by the Foreign Ministry to conduct research on the Hui Muslims of Henan Province.12 The resulting report, “Muslims in Henan” (Kanan no kaikyōto 河南の回教徒), made reference to Ibrahim’s writings (JACAR: B12081600100; B12081600200).

Nakakuki went one step further, however, declaring that Muslims—both Turkic and Hui—could serve as a possible trigger for future political disturbances in China. According to Nakakuki, “the den of the Muslims in all of China” was Ili, where both Russians and Chinese were struggling to assert political control. In another report, Nakakuki argued that it was imperative for Japan to facilitate connections between Muslims on the Russian and Chinese sides of the border, with the ultimate goal of fomenting broader opposition to the Russian presence in Central Asia (JACAR: B12081600100). Here we can see an early iteration of Japan’s own pan-Asian discourse, which was formulated not only in the context of a Sino-Japanese rivalry, but also in the context of a Russo-Japanese rivalry for the hearts and minds of Muslims.

About the Author

Jin Noda 野田仁 is an associate professor in the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan. He specializes in research on the history of international relations in Central Asia, with particular emphasis on Russo-Qing relations. He is the author of The Kazakh Khanates between the Russian and Qing Empires: Central Eurasian International Relations during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Leiden: Brill, 2016). E-mail: <nodajin@aa.tufs.ac.jp>.

References

Bodde 1946

Derk Bodde. “Japan and the Muslims of China.” Far Eastern Survey 5, no. 20 (1946): 311–13.

Esenbel 2018

Selçuk Esenbel. “Fukushima Yasumasa and Utsunomiya Tarō on the Edge of the Silk Road: Pan-Asian Visions and the Network of Military Intelligence from the Ottoman and Qajar Realms into Central Asia.” In: S. Esenbel, ed., Japan on the Silk Road: Encounters and Perspectives of Politics and Culture in Eurasia, Leiden: Brill, 2018: 87–117.

Fang 2000

Fang Jianchang 房建昌. “Jindai riben shentou Xinjiang shulun” 近代日本渗透新疆述论 [On the modern Japanese invasion of Xinjiang]. Xiyu yanjiu 西域研究 (2000), No. 4: 46–53.

Fujita 2000

Fujita Yoshihisa 藤田佳久. Tōa Dōbun Shoin chūgoku dairyokōki no kenkyū 東亞同文書院中國大調查旅行の研究 [A Study of Toa Dobun Shoin’s great journeys in China]. Tokyo: Taimeidō, 2000.

Grekov 2000

N. Grekov. Russkaia kontrrazvedka v 1905–1917 gg.: shpionomaniia i real’nye problem [Russian counterintelligence during 1905–1917: the spy mania and real problems]. Moscow: Moskovskii obshchestvennyi nauchnyi fond, 2000.

Hatano 1907

Hatano Yōsaku 波多野養作. Shinkyō shisatsu fukumeisho 新疆視察復命書 [Report of the investigation in Xinjiang]. Tokyo: Political Affairs Bureau of Foreign Ministry, 1907. In: JACAR: B03050331500.

Hayashide 1907

Hayashide Kenjirō 林出賢次郞. Shinkoku shinkyōshō iri chihō shisatsu fukumeisho 清國新疆省伊犁地方視察復命書 [Report of the investigation on the Ili region in Qing’s Xinjiang province]. Tokyo: Political Affairs Bureau of Foreign Ministry, 1907. In: JACAR: B03050331600 and B03050331700.

Hayashide 1938

———. “30nen mae ni okeru ‘ili’kō no kaiko” [Memory of a journey to Ili 30 years ago]. Shina 29, no. 6 (1938): 172–73.

Hino 1973

Hino Tsutomu 日野强. Iri kikō 伊犁紀行 [The journey to Ili]. Tokyo: Fuyō shobō, 1973 [1909]).

Komatsu 2018

Komatsu Hisao. “Abdurreshid Ibrahim and Japanese Approaches to Central Asia.” In: S. Esenbel, ed., Japan on the Silk Road: Encounters and Perspectives of Politics and Culture in Eurasia, Leiden: Brill, 2018: 145–54.

Kuzuu 1933

Kuzuu Yoshihisa 葛生能久. Tōa senkaku shishi kiden 東亞先覺志士記傳 [Biographical Memoirs of Pioneer Patriots in Eastern Asia]. Vol. 1. Tokyo: Kokuryukai Shuppanbu, 1933.

Kuzuu 1936

———. Tōa senkaku shishi kiden 東亞先覺志士記傳 [Biographical Memoirs of Pioneer Patriots in Eastern Asia]. Vol. 3. Tokyo: Kokuryukai Shuppanbu, 1936.

JACAR

Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (Ajia rekishi shiryō sentā アジア歴史資料センター). Available online: http://www.jacar.go.jp

Mori and Toktoh 2010

Mori Hisao 森久男 and Uljei Toktoh ウルジトクトフ. “Tōa dōbun shoin no naimoko chosa ryoko” 東亜同文書院の内蒙古調査旅行 [Research tours of Toa Dobun Shoin College in Inner Mongolia]. Aichi Daigaku Kokusai mondai kenkyūsho kiyō (2010), No. 136: 141–65.

Mannergeim 1909

Karl Gustav Mannergeim. “Predvaritel’nyi otchet o poezdke, predpriniatoi po Vysochaishemu poveleniiu cherez Kitaiskii Turkestan i severnye pro-vintsii Kitaia v g. Pekin v 1906–7 i 8 gg” [Preliminary report on the trip undertaken by imperial order through Chinese Turkestan and the northern provinces of China to Beijing in 1906–7 and 1908] Sbornik geograficheskikh, topograficheskikh I statisticheskikh materialov po Azii LXXXI (1909): 81–135.

Nishi 1886

Nishi Tokujirō 西德二郎. Chū ajia kiji 中亞細亞記事 [Description of Central Asia]. Tokyo: Rikugun bunko, 1886.

Noda 2010

Noda Jin. “Reconsidering the Ili Crisis: The Ili region under the Russian Rule (1871-1881).” In: M. Watanabe and J. Kubota, eds., Reconceptualizing Cultural and Environmental Change in Central Asia: An Historical Perspective on the Future, Kyoto: RIHN, 2010: 163–97.

Noda 2016

———. The Kazakh Khanates between the Russian and Qing empires: Central Eurasian International Relations during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Obukhov 2016

Vadim G. Obukhov. Bitva za Belovod’e: Bol’shaia Igra nachinaetsia [The battle for the Kingdom of Opona: the Great Game begins]. Moscow: Kraft, 2016.

Ōsato 2013

Ōsato Hiroaki 大里浩秋, ed. “Munakata Kotarō nikki, Meiji 41–42 nen” 宗方小太郎日記, 明治41–42年 [The diary of Munakata Kotaro: 1908–1909]. Jinbungaku kenkyūsyohō (2013), No. 50: 115–69.

Osmanov 2005

E.M. Osmanov. Iz istorii russko-iaponskoi voiny 1904–05 gg.: sbornik materialov k 100-letiiu so dnia okonchaniia voiny [From the history of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904–05: collection of materials from the 100 years since the end of the war]. St. Petersburg: S-Peterburgskogo universiteta, 2005.

Qurbān ‘alī 1910

Qurbān ‘alī Khālidī. Tavārīkh-i khamsa-yi sharqī [Histories of the Five Easterns]. Qazān, 1910.

Reynolds 1986

Douglas R. Reynolds. “Chinese Area Studies in Prewar China: Japan’s Tōa Dōbun Shoin in Shanghai, 1900–1945.” Journal of Asian Studies 45, no. 5 (1986): 945–70.

Reynolds 1989

———. “Training Young China Hands: Tōa Dōbun Shoin and Its Precursors, 1886-1945.” In: Peter Duus et al., eds., The Japanese Informal Empire in China, 1895-1937, Princeton: Princeton University press, 1989: 210–71.

RGVIA

Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi voenno-istoricheskii arkhiv [Russian State Military History Archive]. Moscow.

Shirasu 2012

Shirasu Jōshin 白須淨眞. Ōtani tankentai kenkyū no aratana chihei: Ajia kōiki chōsa katsudō to gaimushō gaikō kiroku 大谷探検隊研究の新たな地平: アジア広域調査活動と外務省外交記録 [New research on Otani’s explorations: Japan’s wide-area investigation in Asia and the diplomatic record of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs]. Tokyo: Bensei shuppan, 2012.

Smirnov 2007

A.S. Smirnov. “Baron Mannergeim vypolnil razvedzadanie rossiiskogo General’nogo shtaba. 1906–1908 gg.” [Baron Mannerheim fulfilled the reconnaissance works of the Russian General Staff Office in 1906–08]. Voenno-istoricheskii zhurnal 2 (2007): 24–27.

Snesarev 1907

A.E. Snesarev. “Islam, kak politicheskoe orudie v rukakh anglichan, germantsev i iapontsev” [Islam as a political way in the hands of the English, German, and Japanese]. Zakaspiiskoe obozrenie 2 (1907): 66–69.

Teramoto 1974

Teramoto Enga 寺本婉雅. Zō-Mō tabinikki 藏蒙旅日記 [Travelogue of Tibet and Mongolia]. Tokyo: Fuyō Shobō, 1974.

Terayama 2015

Terayama Kyōsuke 寺山恭輔. Sutārin to Shinkyō: 1931–1949 新疆とスターリン: 1931–1949 [Stalin and Xinjiang, 1931–49]. Tokyo: Shakai hyōron sha, 2015.

TsGA RK

Tsentral’nyi gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Respubliki Kazakhstan [Central state archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan]. Almaty.

Wang 2013

Wang Ke 王柯. Dong Tujuesitan duli yundong: 1930 niandai zhi 1940 niandai 东突厥斯坦独立运动:1930年代至1940年代 [East Turkestan independence movement: 1930s to 1940s]. Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chubanshe, 2013.

Wang 2015

———. Minzu zhuyi yu jindai zhongri guanxi: “minzu guojia” “bianjiang” yu lishi renshi 民族主义与近代中日关系:《民族国家》《边疆》与历史认识 [Nationalism and modern Sino-Japanese relations: nation state, borderland, and historical knowledge]. Hong Kong: Zhongwen daxue chubanshe, 2015.

Yamashiro 2015

Yamashiro Tomofumi 山城智史. “1870 nendai ni okeru nissin kanno gaikō anken toshiteno ryūkyū kizoku mondai” 1870年代における日清間の外交案件としての琉球帰属問題 [The diplomatic issue of Ryukyu attribution between Japan and China in the 1870s]. Kenkyū nenpō shakai kagaku kenkyū 研究年報社会科学研究 (Yamanashigakuin University)] (2015), No. 35: 95–125.

Yamazaki 2014

Yamazaki (Unno) Noriko. “Abdürreşid İbrahim’s journey to China: Muslim communities in the late Qing as seen by a Russian-Tatar intellectual.” Central Asian Survey 33, no. 3 (2014): 405-20.

Yang and Chai 2014

Yang Wenjiong 杨文炯 and Chai Yalin 柴亚林. “Qingmo zhi minguo shiqi riben zai woguo xinjiangde yinmou huodong shulüe” 清末至民国时期日本在我国新疆的阴谋活动述略 [A concise report on Japan’s intelligence activity in Xinjiang during the late Qing and Republican period]. Zhongguo bianjiang shidi yanjiu 中国边疆史地研究 (2014), No. 4: 110–17.

Endnotes

1 For related archival materials concerning Western Siberia, see Grekov 2000. The Russian State Military History Archive (RGVIA) also contains documents regarding the Japanese interest in Xinjiang.

2 See, for example, Yang and Chai (2014).

3 JACAR (Ajia rekishi shiryō sentā アジア歴史資料センター) mainly contains materials provided by the National Archives of Japan (Kokuritsu kōmonjokan 國立公文書館), the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (Gaimushō gaikou shiryōkan 外務省外交史料館), and the National Institute for Defense Studies (Boueishō bouei kenkyūsho 防衛省防衛研究所).

4 See, for example, a May 19, 1906 report from Kamio Mitsuomi, Commander of the China Garrison Army, to Minister of the Army Terauchi (JACAR: C10071807400).

5 For more on the East Asia Common Culture Academy and its graduates, see Reynolds 1986. Reynolds has also looked at the explorers sent to Xinjiang, though with only limited materials (Reynolds 1989: 236). For a general overview of these explorations, see Mori and Toktoh 2010.

6 On Uehara’s later intelligence activity in Russian Turkestan in 1912, see Obukhov 2016 (615).

7 Hino did, however, publish a travelogue of his journey in 1909, providing general background information about his trip (Hino 1973).

8 According to Smirnov (2007), Mannerheim, whose travels were approved by the Tsar, sent his reports directly to the General Staff Office.

9 I would like to thank David Brophy for information concerning Sa‘id Muhammad al-‘Asālī.

10 On these Tatar migrants, who had engaged in trade in northern Xinjiang since the nineteenth century, see Noda 2016.

11 At the same time, Hino encouraged the construction of railroads by the Qing (1973: v. 1, 188 and v. 2, 160).

12 Nakakuki’s assignment was also noted by Wang Ke (2015: 194). For more on Nakakuki, see Bodde (1946) and Kuzuu (1936: 356). On relations between Nakakuki and Ibrahim, see Yamazaki 2014 (413). Since Nakakuki was on close terms with Munakata Kotarō (1864-1923), who took part in the activities of the Rakuzen-dō, he was also likely a Pan-Asianist (Ōsato 2013).

* This is a revised and shortened version of my previously published article, “Nippon kara chūōajia eno manazashi: Kindai shinkyō to nichiro kankei” 日本から中央アジアへのまなざし : 近代新疆と日露関係 [How did Japan look at Central Asian Muslims? Xinjiang in Russo-Japanese relations in the early twentieth century], Journal of Islamic Area Studies 6 (2014): 11–22.