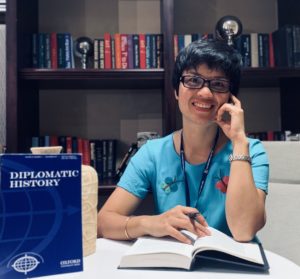

When Nguyet Nguyen first came to the United States from Vietnam, the culture shock was profound. Having won a Fulbright scholarship to pursue a master’s degree in Communications at the University of Oregon in 2007, Nguyen struggled to adapt to even the most trivial aspects of daily life in America. “The cultural shock was astounding,” she recalled. “I didn’t know American slang or customs and I was very naïve. I didn’t even know how to use doorknobs or bathrooms, or how to ride the bus.” Her refuge was in the classroom, where Nguyen gained a reputation for “asking the sort of questions that American students are too embarrassed to ask.” After obtaining an M.A. in Communications in 2009, Nguyen was admitted to the doctoral program in history at American University, where she wrote a dissertation on the Vietnam War under the supervision of Max Paul Friedman.

With the completion of her Ph.D. in 2019, Nguyen was awarded the Janet Oppenheim Postdoctoral Fellow. This fellowship provides her with the opportunity to teach an undergraduate course on the Vietnam War, conduct additional research, and revise her dissertation into a book manuscript. Her class on the Vietnam War strives to introduce new perspectives that are often overlooked or ignored in conventional American narratives. “Most people think of the war as a noble anti-communist cause that went wrong,” she said. “If only we had done this right or that right, or if we had understood the Vietnamese better, it all would have ended differently.” By contrast, Nguyen draws attention to the many other areas of geopolitical self-interest across Southeast Asia that encouraged growing U.S. involvement in the war, regardless of Cold War ideologies. “Even if our methods had been right,” she adds, “the intention still was not right. The intention was always to divide the country into two. This means that war would have continued regardless.”

Nguyen believes that there is still a lot of healing that needs to be done with regard to the war. But in order to facilitate such healing, we first need to let go of our cherished myths concerning the origin of the conflict. Ken Burns’s ten-part documentary series on the Vietnam War, which first aired on PBS in 2017, was a step in the right direction, Nguyen said. She was impressed to see that it included Vietnamese perspectives as well as those of the Americans. “But what it didn’t say is just as important as what it did say,” Nguyen observed. “It still hammered home the idea that the spread of communism was the chief motivating factor in the American decision to join the war, and reinforced the idea that U.S. leaders were simply naïve and overly optimistic. It avoided discussing all the other areas of self-interest that the U.S. had in Southeast Asia at the time—interests that ensured U.S. involvement in Vietnam sooner or later.”

Once she completes her postdoctoral fellowship at AU, Nguyen hopes to publish her book and find a job as a professor of history at a university in the United States. “I could never talk this openly about the Vietnam War if I taught this subject back in Vietnam,” she noted. Her dream, she said, “is to become a professor in a department just like this one—the AU History Department is the best!”