Portraits

In several depictions of Black African children with other children of European heritage, we see similarities in their clothing where they are clothed and adorned to show off their status of their masters. However, in many cases, the white slaves and servants are not seen wearing collars, gold jewelry and pearl-drop earrings as their black counterparts. Africans at the grander European courts and sometimes in the smaller ones might be ambassadors from African countries, members of the court bureaucracy, dancers, acrobats, and musicians, and slaves and servants both to the household and to individuals, male and female. However, in many cases that will be discussed, the Black African becomes an object placed in the setting or apart of the aesthetic of the portrait or group portrait.

Bindman argues that the genre of master/mistress accompanied by an adoring servant/slave was essentially invented by Titian, and that the first identifiable example is Portrait of Laura dei Dianti (ca.1523) (Fig. 19).[58] Titian deployed stripes and earrings in portraits to elevate the white European subjects in his works. This is the case with his painting of Portrait of Laura dei Dianti, mistress to Duke Alfonso of Ferrara, the brother of Isabelle d’Este. The sitter wears a radiant blue dress, expensive jewelry, and an eloquent diadem. Her right arm runs down the side of her body while her left hand rests on the shoulder of a small, probably male Black attendant in an elaborately colorfully striped garment and golden double-pierced earrings. He looks up adoringly at his mistress, holding a pair of decorative gloves presumed to be Laura’s in further conveyance of his status of servitude. The position of Laura’s hand on the child’s shoulder suggests his inferiority, as in the case in other portraits that include the kinds of young Black children who were so prized at European courts. Laura’s elite social status could have been conveyed without including the child. He fills an ornamental, aggrandizing role in the portrait, and her fair skin tone is highlighted by contrast with his dark flesh. The smaller, Black child marks her as an aristocrat who shares the same fashionable taste as her lover’s family.[59] While the child is seemingly well cared for, their striped silk costume signifies the wealth at Laura’s disposal rather than the financial or social status of the child. Court jesters were often depicted wearing stripes and bright colors and, when considering Isabella d’Este’s use of the term buffone to describe a Black African child, it would seem that the child depicted by Titian was a source of entertainment for Isabella and her courtiers.[60] Mellinkoff states that the colors yellow and green were often used when defining someone as a fool, but red was also popular, as was the combination of using all three colors which is shown in the painting (Fig. 19).[61] Costuming produces a striking contrast between Laura and the small child because Laura wears a richly woven, elaborate jeweled embroidered dress as a sign of her status, while the child does not.

(Fig.20) Titian, Portrait of FabriziomSalvaressa, 1558. Oil on canvas, Kunsthisto- risches Museum, Vienna

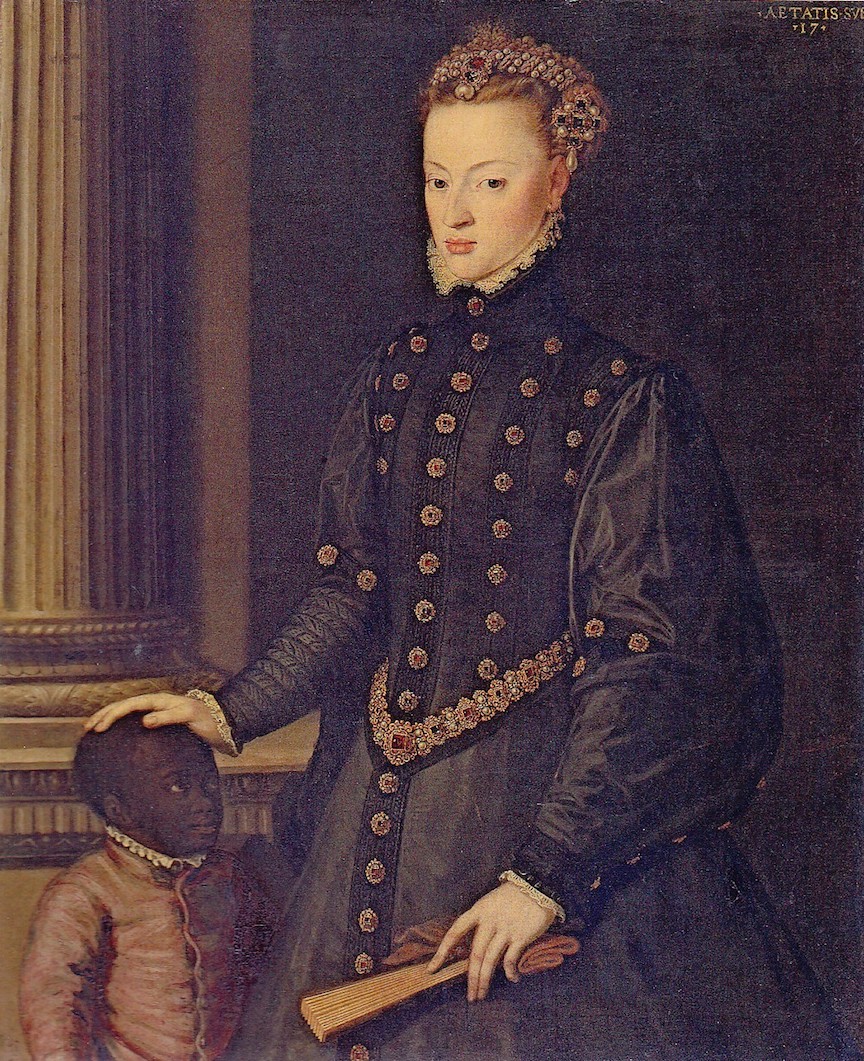

(Fig.21) Cristóvão de Morais, Portrait of Juana of Austria with her Black Slave Girl, 1553. Oil on canvas. Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

(Fig.22) Johannes Mijtens, Portrait of Margaretha van Raephorst, 1668. Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Netherlands.

Many other examples of portraits that use race as a means of shoring up white hegemony were produced in Renaissance Italy. An example of this is shown in Titian’s Portrait of Fabrizio Salvaressa (Fig. 20) (1558), Cristóvão de Morais’s Portrait of Juana de Austria with her Black Slave Girl (1553) (Fig. 21), Johannes Mijtens’ Portrait of Margaretha van Raephorst (1668) (Fig.22), and Anton Domenico Gabbiani’s Portrait of Three Musicians of the Medici Court (c.1687) (Fig.23). In Titian’s painting he depicts the Venetian merchant Fabrizio Salvaressa accompanied by a Black male child at the lower right. Salvaressa is dressed in all black. His confidence and stature are conveyed by his firm grasp of a decorative sash at his waist and by his direct eye contact with the viewer. By contrast, the attendant is shown in profile, his body bifurcated by picture’s spatial frame. He looks directly up towards Salvaressa, mouth slightly agape, and offering an honorific bouquet to the subject of his adoration. The boy’s elegant clothing conveys Salvaressa’s wealth: in this, he glorifies his enslaver.

A similar approach to aggrandization through race is Cristóvão de Morais’s Portrait of Juana de Austria with her Black Slave Girl (Fig. 21). The small child was a wedding gift to Juana from her husband, Prince João, as a 1574 inventory attests.[62] Juana’s mother-in-law, Catherine of Austria, commissioned the painting. Juana is shown in an all-black velvet and satin dress embellished with jewels, sartorial adornments suited to her status. The small Black girl to her side stares admirably up at her. Rather than return that gaze, Juana looks to the viewer, as in Titian’s Portrait of Fabrizio Salvaressa discussed previously. The placement of Juana’s hand stands squarely on the small child’s head is not only a sign of ownership of the girl but also of the dehumanization of the enslaved person. Catherine of Austria owned several enslaved Africans and often gave her close friends enslaved Africans as gifts; perhaps this was the case here.[63] Although Renaissance royalty often chose the color black for wedding garments, it and the dark skin of the child heighten the whiteness of her skin and, in so doing, marked it more clearly as a sign of status.[64] The Black child, akin in color to the gown, becomes like it, another accessory that glorifies the painting’s primary subject.

(Fig. 24) Johannes Mytens, Portrait of Maria of Orange, with Hendrik van Zuijlestein, and a Servant, (c.1665). Oil on canvas. Mauritshuis, Netherlands.

The Netherlandish artist and court painter of the Stadholder family, Johannes Mijtens, painted several works that incorporate Black African servants in group portraits where earrings and patterned clothing are used to assign lesser status to the figures. In Portrait of Maria of Orange, with Hendrik van Zuijlestein, and a Servant (c. 1665) (Fig. 24), the youngest daughter of the family, Princess Maria of Orange, is shown in the foreground glaring directly out at the viewer. She wears a large, white, feathered hat and an elegant embroidered riding habit. The blond boy on the left is Hendrik, the son of Maria’s half-brother, in the process of tying red string on Maria’s habit. To Maria’s right and placed behind the two figures stands a Black page holding the reins of her grey horse. The page looks at Maria in admiration, much like the child in Titian’s Laura dei Dianti (Fig. 19). Unlike Maria and Hendrik, his identity is unknown, but his status is communicated via his worn, multi-colored outfit, striped collar and belt, and the large pearl shaped earring. Mijtens use of the combination of stripes and an earring can be seen in a similar group portrait called The Family of Mr. Willem van den Kerckhoven and Reijmerick de Jonge (c. 1652) (Fig. 25).