PART I | THE GENDERED CYBORG

THE SEXY ROBOT

AND ITS ORIGINS IN EAST ASIA

The modern conception of the cyborg originated in Europe, so the East Asian cyborg emerged in the country that most consciously modeled itself after Western powers since the mid-nineteenth century: Japan. The abundance of cyborg depictions in Japanese culture, as well as Japan’s perceived “obsession” with the technological has led several scholars to note that the country seems to have a “special relationship with the cyborgian.”[21] In her chapter on the genealogy of the cyborg in Japanese culture, Sharalyn Orbaugh begins by tracing the origin of the “mecha-suit” (giant metal fighting suit piloted by a person), which was one of the most prevalent cyborg representations in Post-WWII Japan. When the formerly isolated island nation was forced to open its borders in 1868, intellectuals and reformers looked to America and Europe as models for modernization.

One aspect of this was translating Western literature into Japanese, and the adventure novels of Jules Verne became exceptionally popular and influential in this period. Verne’s confident protagonists, futuristic transportation technology, and the theme of freeing the human mind from the limitations of the body all became hallmarks of the new technophilic genre of boken shosetsu (adventure novel).[22] Orbaugh characterizes the development of this “hardware-technophilic stream of Japanese cyborg narrative” as a response to the conditions of Japan’s modernization: to avoid being colonized by more ‘advanced’ nations, Japan had to make itself in its (potential) colonizer’s image, quickly reproducing Western technological and military advancements.[23] However, this cause-and-effect relationship does not fully explain the complex and empathetic nature of Japanese cyborg representations. Orbaugh relates these aspects to what she calls “Frankenstein Syndrome,” an experience faced by developing nations in which they recognize their own “monstrosity” within hegemonic Western discourse.[24] Like the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, who was rejected by his creator and all other people he encountered, people in modernizing Japan, despite successfully replicating the science, technology, economy, and military of Western nations, were repeatedly reminded of their own racial inferiority and “monstrosity” in the eyes of the West.[25] Because of this, Orbaugh concludes, Japanese cyborg narratives explore monstrous subjectivities from a “sympathetic, interiorized” perspective.[26] This accounts for the more complex portrayal of cyborgs in Japanese media in terms of narrative, but does not account for the visual forms of the cyborg, innovated by Sorayama Hajime and films like Ghost in the Shell.

Representations of cyborgs in popular culture and visual art have flourished since the Second World War, especially in North America and Japan.[27] In these media, cyborgs are used as a medium to explore contemporary anxieties regarding technology, postmodern subjectivity, the meaning of the body, and, most importantly for this paper, sex and gender difference.[28] While Haraway characterized the cyborg as a “creature in a post-gender world” that could help imagine a post-gender society, cyborgs in popular culture are not outside the binary system of gender and sex that structures society.[29] Orbaugh has noted that despite the original, feminist formulation of the cyborg as post-gendered, “contemporary Japanese cyborg narratives are still very much concerned with the binary oppositions of sex and gender.”[30]

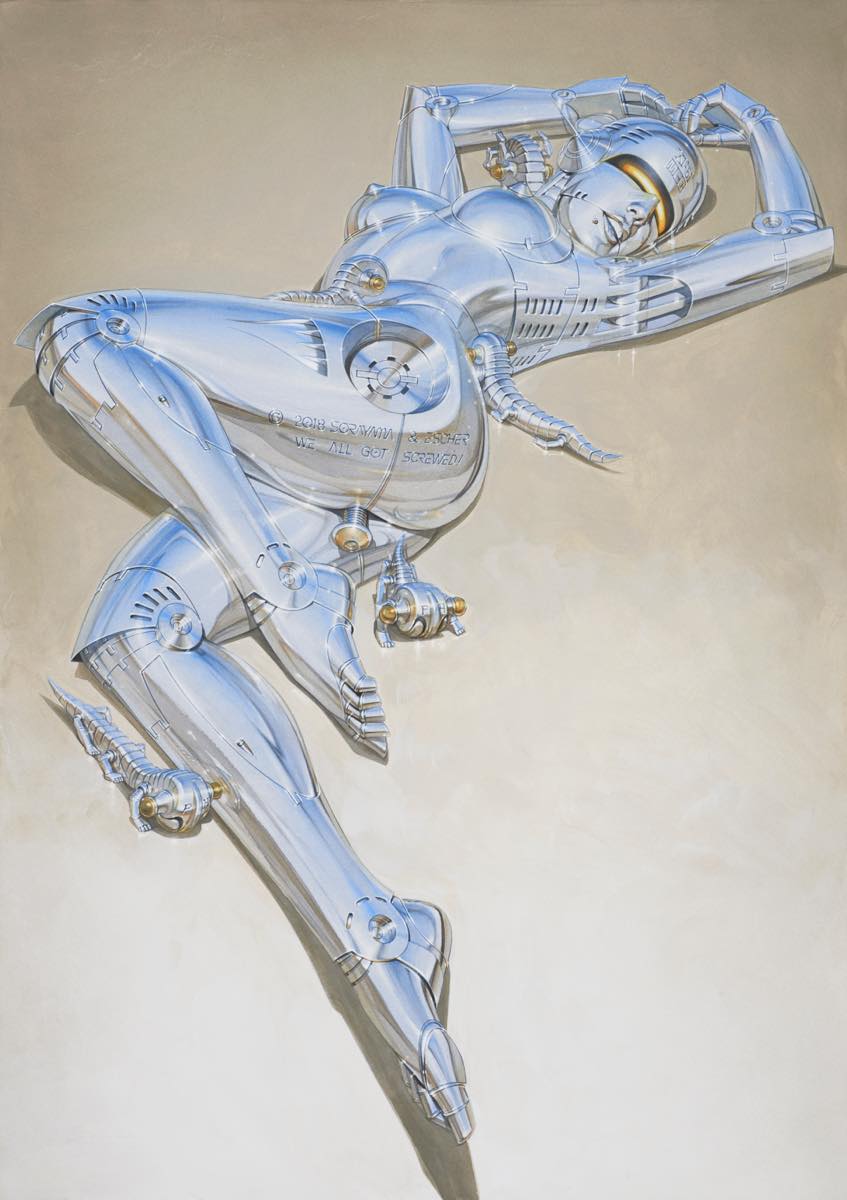

Figure 2: Sorayama Hajime, HS_Paint_163, 2018. Pencil and acrylic illustration.

Figure 3: iPhone XR advertisement, 2018. See https://youtu.be/1EnDE-Sd_fw.

Japanese depictions of cyborgs continually reinforce gendered divisions, and this is evident in the visual differences between male and female cyborg bodies. Namely, female cyborg bodies are presented in a hyper-sexualized, idealized manner that emphasizes secondary sex traits (especially breasts), while male cyborg bodies are not sexualized. The exact origins of this model are unclear, but Sorayama Hajime’s illustrations of “sexy robots” were a key influence in the development of fetishized and technologized depictions of the female body. The earliest and most prominent example of the sexy cyborg in manga and anime is the female cyborg Motoko Kusanagi in Shirow Masamune’s manga Ghost in the Shell (1989-1991) and Mamoru Oshii’s film adaptation (1995), and Shirow has cited Sorayama as an influence on his style.[31]

Born in 1947, Sorayama Hajime has worked in advertising and illustration since the late 1960s and began illustrating robots by 1978. He is most famous for his “superreal”[32] drawings of “sexy robots,” which Sorayama modeled after the pin-up images of famous Hollywood actresses that fascinated him as a youth.[33] The association with pin-ups, which Sorayama deliberately alludes to in the framing and posing of his figures, implies a relationship with the voyeuristic male gaze. It is important to note that almost all of his images of sexy robots are gynoids (female robots) that are provocatively posed in ways that emphasize their idealized and sexualized bodies.[34] In HS_Paint_163 (figure 2), the gynoid sprawls on the floor with arms upstretched, her body twisted to reveal both breasts and buttocks at the same time. She is a spectacle of curves, her skin rendered as a shiny metallic surface that is reminiscent of the lure of technology present in sleek smartphone ads, for example (figure 3). Sorayama’s signature is visually etched into the back of her upper thigh, almost like a stamp of ownership, along with a cheeky slogan reading, “we all got screwed!,” referencing the large screw that suggestively penetrates the gynoid’s genital area. What is the effect of this depiction of the mechanized female body as sexualized and commodified? Scholars like Andreas Huyssen have argued that the combination of technology and female sexuality in media and art often reflects a reframing of the fear of technology in the terms of male fear of female sexuality.[35] However, the mechanical woman also represents a form of femininity that is easily controlled by men, allowing for the possibility of discarding actual women in favor of the more manageable, and even programmable, machine-woman.[36] As Thomas Foster summarized, “in this representational framework, the analogy between technology and female sexuality confirms that both represent a threat to masculine power, while the conflation of the two in the form of the female robot allows for a specifically fetishistic disavowal of both threats.”[37] In other words, combining the form of a sexualized female body with technology in the machine-woman represents the containment of the threats of both female sexuality and technology for the benefit of the male viewer.

However, Foster contested this narrative, claiming that Sorayama’s illustrations undermine the process of male erotic viewing.[38] He argued that the combination of the technological and the female body in the artist’s work provokes male anxiety rather than dispelling it, and in fact can be read as a literal and metaphorical “reflection” of the construction of male heterosexual desire.[39] According to Foster, Sorayama’s sexy robots “seem designed to elicit both a sexual response and an uncomfortable recognition of the inappropriateness, perhaps even obsolescence, of that response.”[40] That is, several factors in the images, including the ambiguity of whether these are machines designed to look like female bodies or women becoming machines, compromises the straightforward sexual appeal of these images. Though the artist is clearly a master of his craft, I disagree with Foster’s argument that Sorayama interrupts the erotic experience of a viewer seeing these works. Rather than undermining the voyeuristic viewing process, his sexy robots perpetuate the objectification and subjugation of the female body, albeit in a more robotic form. In HS_Paint_138 (figure 4) and HS_Paint_141 (figure 5), Sorayama has rendered the robotic female body in the sensuous, lustrous fashion that is characteristic of his style. These two images, along with HS_Paint_163, should be read as incarnations of, rather than subversions of, male fantasies, because of how they situate the female robots in positions of submissive, objectified eroticism. The figures are bound in chains, which compress their forms as if they had skin instead of metal. This detail visually brings the figures closer to the soft and pliant form of the idealized female body, and farther away from the powerful, and therefore threatening, robot body. Despite not looking like “real” women, these female robots can still feel like real women, with soft and supple flesh. Additionally, the chains, as an instance of bondage, restrict the figures’ movement and place them in the submissive sexual role, while the male viewer implicitly takes the dominant, controlling position. Rather than functioning as uncanny images of male anxiety, these female robots create a fantasy in which the male viewer takes pleasure in these objectifying images of sexual submission. This sexy and technological female form created by Sorayama is the East Asian template for the sexualized representation of the female cyborg that later flourished in popular and far-reaching manga and anime of the 1980s and 90s.

In her dissertation on representations of cyborgs, ghosts, and monsters in contemporary science fiction media, Kuo Wei Lan surveys several prominent films and anime within the context of Japanese history and culture, concluding that Japanese depictions of cyborgs are representative of male fantasies and anxieties and reinforce patriarchal ideology.[41] Kuo discussed multiple types of female cyborgs that uphold the tenets of patriarchy, but the most important example for this paper is the violent and sexualized female cyborg, whose form was recreated by both Fan Xiaoyan and Lee Bul. In depictions of this type, female-appearing cyborg bodies are repeatedly sexualized for the voyeuristic pleasure of the audience, while also being mutilated and exploded, deprived of reproductive potential, and denied expressions or realizations of sexuality.[42] They also commit acts of violence, displaying the power of their aesthetically perfect bodies; however, this does not necessarily evoke male fears of female sexuality and technology. Rather, because the female cyborg’s physical prowess comes from her technological attachments,

it can be argued that the female cyborg looks like a woman but acts like a man because the female cyborg’s aggression, dominance, and toughness is not derived from her biological femininity but from the technological phallicisation of her hybrid body.[43]

The modern conception of the cyborg originated in Europe, so the East Asian cyborg emerged in the country that most consciously modeled itself after Western powers since the mid-nineteenth century: Japan. The abundance of cyborg depictions in Japanese culture, as well as Japan’s perceived “obsession” with the technological has led several scholars to note that the country seems to have a “special relationship with the cyborgian.”[21] In her chapter on the genealogy of the cyborg in Japanese culture, Sharalyn Orbaugh begins by tracing the origin of the “mecha-suit” (giant metal fighting suit piloted by a person), which was one of the most prevalent cyborg representations in Post-WWII Japan. When the formerly isolated island nation was forced to open its borders in 1868, intellectuals and reformers looked to America and Europe as models for modernization.

One aspect of this was translating Western literature into Japanese, and the adventure novels of Jules Verne became exceptionally popular and influential in this period. Verne’s confident protagonists, futuristic transportation technology, and the theme of freeing the human mind from the limitations of the body all became hallmarks of the new technophilic genre of boken shosetsu (adventure novel).[22] Orbaugh characterizes the development of this “hardware-technophilic stream of Japanese cyborg narrative” as a response to the conditions of Japan’s modernization: to avoid being colonized by more ‘advanced’ nations, Japan had to make itself in its (potential) colonizer’s image, quickly reproducing Western technological and military advancements.[23] However, this cause-and-effect relationship does not fully explain the complex and empathetic nature of Japanese cyborg representations. Orbaugh relates these aspects to what she calls “Frankenstein Syndrome,” an experience faced by developing nations in which they recognize their own “monstrosity” within hegemonic Western discourse.[24] Like the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, who was rejected by his creator and all other people he encountered, people in modernizing Japan, despite successfully replicating the science, technology, economy, and military of Western nations, were repeatedly reminded of their own racial inferiority and “monstrosity” in the eyes of the West.[25] Because of this, Orbaugh concludes, Japanese cyborg narratives explore monstrous subjectivities from a “sympathetic, interiorized” perspective.[26] This accounts for the more complex portrayal of cyborgs in Japanese media in terms of narrative, but does not account for the visual forms of the cyborg, innovated by Sorayama Hajime and films like Ghost in the Shell.

Representations of cyborgs in popular culture and visual art have flourished since the Second World War, especially in North America and Japan.[27] In these media, cyborgs are used as a medium to explore contemporary anxieties regarding technology, postmodern subjectivity, the meaning of the body, and, most importantly for this paper, sex and gender difference.[28] While Haraway characterized the cyborg as a “creature in a post-gender world” that could help imagine a post-gender society, cyborgs in popular culture are not outside the binary system of gender and sex that structures society.[29] Orbaugh has noted that despite the original, feminist formulation of the cyborg as post-gendered, “contemporary Japanese cyborg narratives are still very much concerned with the binary oppositions of sex and gender.”[30]

Figure 2: Sorayama Hajime, HS_Paint_163, 2018. Pencil and acrylic illustration.

Japanese depictions of cyborgs continually reinforce gendered divisions, and this is evident in the visual differences between male and female cyborg bodies. Namely, female cyborg bodies are presented in a hyper-sexualized, idealized manner that emphasizes secondary sex traits (especially breasts), while male cyborg bodies are not sexualized. The exact origins of this model are unclear, but Sorayama Hajime’s illustrations of “sexy robots” were a key influence in the development of fetishized and technologized depictions of the female body. The earliest and most prominent example of the sexy cyborg in manga and anime is the female cyborg Motoko Kusanagi in Shirow Masamune’s manga Ghost in the Shell (1989-1991) and Mamoru Oshii’s film adaptation (1995), and Shirow has cited Sorayama as an influence on his style.[31]

Born in 1947, Sorayama Hajime has worked in advertising and illustration since the late 1960s and began illustrating robots by 1978. He is most famous for his “superreal”[32] drawings of “sexy robots,” which Sorayama modeled after the pin-up images of famous Hollywood actresses that fascinated him as a youth.[33] The association with pin-ups, which Sorayama deliberately alludes to in the framing and posing of his figures, implies a relationship with the voyeuristic male gaze. It is important to note that almost all of his images of sexy robots are gynoids (female robots) that are provocatively posed in ways that emphasize their idealized and sexualized bodies.[34] In HS_Paint_163 (figure 2), the gynoid sprawls on the floor with arms upstretched, her body twisted to reveal both breasts and buttocks at the same time. She is a spectacle of curves, her skin rendered as a shiny metallic surface that is reminiscent of the lure of technology present in sleek smartphone ads, for example (figure 5). Sorayama’s signature is visually etched into the back of her upper thigh, almost like a stamp of ownership, along with a cheeky slogan reading, “we all got screwed!,” referencing the large screw that suggestively penetrates the gynoid’s genital area. What is the effect of this depiction of the mechanized female body as sexualized and commodified? Scholars like Andreas Huyssen have argued that the combination of technology and female sexuality in media and art often reflects a reframing of the fear of technology in the terms of male fear of female sexuality.[35] However, the mechanical woman also represents a form of femininity that is easily controlled by men, allowing for the possibility of discarding actual women in favor of the more manageable, and even programmable, machine-woman.[36] As Thomas Foster summarized, “in this representational framework, the analogy between technology and female sexuality confirms that both represent a threat to masculine power, while the conflation of the two in the form of the female robot allows for a specifically fetishistic disavowal of both threats.”[37] In other words, combining the form of a sexualized female body with technology in the machine-woman represents the containment of the threats of both female sexuality and technology for the benefit of the male viewer.

Figure 3: iPhone XR advertisement, 2018. See https://youtu.be/1EnDE-Sd_fw.

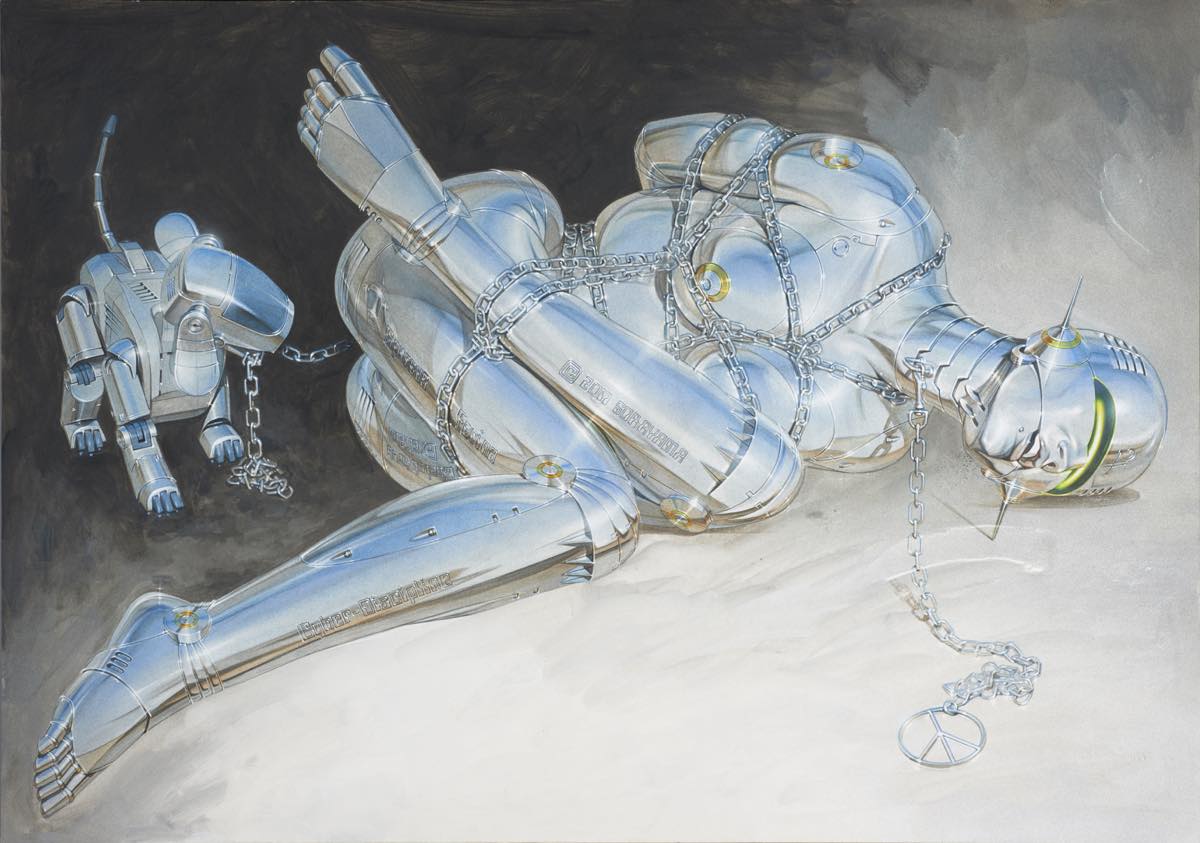

Figure 4: Sorayama Hajime, HS_Paint_138, 2017. Pencil and acrylic illustration.

Figure 5: Sorayama Hajime, HS_Paint_141, 2017. Pencil and acrylic illustration.

However, Foster contested this narrative, claiming that Sorayama’s illustrations undermine the process of male erotic viewing.[38] He argued that the combination of the technological and the female body in the artist’s work provokes male anxiety rather than dispelling it, and in fact can be read as a literal and metaphorical “reflection” of the construction of male heterosexual desire.[39] According to Foster, Sorayama’s sexy robots “seem designed to elicit both a sexual response and an uncomfortable recognition of the inappropriateness, perhaps even obsolescence, of that response.”[40] That is, several factors in the images, including the ambiguity of whether these are machines designed to look like female bodies or women becoming machines, compromises the straightforward sexual appeal of these images. Though the artist is clearly a master of his craft, I disagree with Foster’s argument that Sorayama interrupts the erotic experience of a viewer seeing these works. Rather than undermining the voyeuristic viewing process, his sexy robots perpetuate the objectification and subjugation of the female body, albeit in a more robotic form. In HS_Paint_138 (figure 3) and HS_Paint_141 (figure 4), Sorayama has rendered the robotic female body in the sensuous, lustrous fashion that is characteristic of his style. These two images, along with HS_Paint_163, should be read as incarnations of, rather than subversions of, male fantasies, because of how they situate the female robots in positions of submissive, objectified eroticism. The figures are bound in chains, which compress their forms as if they had skin instead of metal. This detail visually brings the figures closer to the soft and pliant form of the idealized female body, and farther away from the powerful, and therefore threatening, robot body. Despite not looking like “real” women, these female robots can still feel like real women, with soft and supple flesh. Additionally, the chains, as an instance of bondage, restrict the figures’ movement and place them in the submissive sexual role, while the male viewer implicitly takes the dominant, controlling position. Rather than functioning as uncanny images of male anxiety, these female robots create a fantasy in which the male viewer takes pleasure in these objectifying images of sexual submission. This sexy and technological female form created by Sorayama is the East Asian template for the sexualized representation of the female cyborg that later flourished in popular and far-reaching manga and anime of the 1980s and 90s.

In her dissertation on representations of cyborgs, ghosts, and monsters in contemporary science fiction media, Kuo Wei Lan surveys several prominent films and anime within the context of Japanese history and culture, concluding that Japanese depictions of cyborgs are representative of male fantasies and anxieties and reinforce patriarchal ideology.[41] Kuo discussed multiple types of female cyborgs that uphold the tenets of patriarchy, but the most important example for this paper is the violent and sexualized female cyborg, whose form was recreated by both Fan Xiaoyan and Lee Bul. In depictions of this type, female-appearing cyborg bodies are repeatedly sexualized for the voyeuristic pleasure of the audience, while also being mutilated and exploded, deprived of reproductive potential, and denied expressions or realizations of sexuality.[42] They also commit acts of violence, displaying the power of their aesthetically perfect bodies; however, this does not necessarily evoke male fears of female sexuality and technology. Rather, because the female cyborg’s physical prowess comes from her technological attachments,

it can be argued that the female cyborg looks like a woman but acts like a man because the female cyborg’s aggression, dominance, and toughness is not derived from her biological femininity but from the technological phallicisation of her hybrid body.[43]

[21] Sharalyn Orbaugh, “The Genealogy of the Cyborg in Japanese Popular Culture,” in World Weavers: Globalization, Science Fiction, and the Cybernetic Revolution, ed. Wong Kin Yuen, Gary Westfahl, and Amy Kit-Sze Chan (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, 2005), 61. See also Chris Hables Gray, Cyborg Citizen (New York: Routledge, 2001), 165, 191; Bruce Grenville, “The Uncanny: Experiments in Cyborg Culture,” in The Uncanny: Experiments in Cyborg Culture, ed. Bruce Grenville (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2001), 38–48; Ueno Toshiya, “Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism,” 223 ff.

[22] Orbaugh, “The Genealogy of the Cyborg,” 59. This genre was established around the turn of the century.

[23] Orbaugh, “The Genealogy of the Cyborg,” 61.

[24] Orbaugh, “The Genealogy of the Cyborg,” 62.

[25] Orbaugh, “The Genealogy of the Cyborg,” 62.

[26] Orbaugh, “The Genealogy of the Cyborg,” 62.

[27] For further discussion of the cyborg in American culture, see Samantha Holland, “Descartes Goes to Hollywood: Mind, Body and Gender in Contemporary Cyborg Cinema,” in Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment, ed. Mike Featherstone and Roger Burrows (London: SAGE Publications, 1995),

157–74.

[28] Jennifer Gonzalez, “Envisioning Cyborg Bodies: Notes from Current Research,” in The Gendered Cyborg: A Reader, ed. Gill Kirkup, Linda James, and Fiona Hovenden (London: Routledge, 2000), 58.

[29] Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” 8.

[30] Sharalyn Orbaugh, “Sex and the Single Cyborg: Japanese Popular Culture Experiments in Subjectivity,” in Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams: Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime, ed. Christopher Bolton, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., and Takayuki Tatsumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 187.

[31] Ray Mescallado, “Review: Otaku Nation,” Science Fiction Studies 27, no. 1 (2000): 143.

[32] Sorayama defines “superrealism” as a more fantastical variant of hyperrealism, an artistic style that replicates the realistic effect of a high-definition camera. Evan Pricco, “Future Retro Futurist: Sorayama at Jacob Lewis Gallery,” Juxtapoz, November 22, 2016, https://www.juxtapoz.com/news/magazine/future-retro-futurist-sorayama-at-jacob-lewis-gallery/.

[33] The popularity of these Hollywood pinup images in Japan in the postwar period was due to the fact that American popular culture had an incredibly strong presence across East Asia. The presence of these bodies also resonated with the persisting anxiety in Japanese society about the perceived “inferiority” of the Asian body. See Mikkiko Hirayama, “The Emperor’s New Clothes: Japanese Visuality and Imperial Portrait Photography,” History of Photography 33, no.2 (2009): 172-3.

[34] A gynoid is a female humanoid robot, as opposed to an android, which is a “non-gendered” humanoid robot. The existence of a specific word for female-appearing robots belies their prevalence in art and popular culture.

[35] Huyssen’s argument deals with Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis (1927), but his argument can be applied to a range of cyborg/gynoid representations, especially in Western culture. Andreas Huyssen, “The Vamp and the Machine: Technology and Sexuality in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis,” New German Critique, no. 24/25 (1981): 221–37.

[36] Thomas Foster, “The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic: Posthuman Narratives and the Construction of Desire,” in The Souls of Cyberfolk: Posthumanism as Vernacular Theory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 98.

[37] Foster, “The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic,” 98.

[38] Foster, “The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic,” 81–114.

[39] Foster, “The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic,” 102.

[40] Foster, “The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic,” 101.

[41] Kuo Wei Lan, “Technofetishism of Posthuman Bodies: Representations of Cyborgs, Ghosts, and Monsters in Contemporary Japanese Science Fiction Film and Animation” (PhD Dissertation, University of Sussex, 2012), 257.

[42] Kuo, “Technofetishism of Posthuman Bodies,” 208-209.

[43] Kuo, “Technofetishism of Posthuman Bodies,” 197.

[44] Jeffrey A. Brown, Dangerous Curves: Action Heroines, Gender, Fetishism, and Popular Culture (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011), 81-88.