PART I | THE GENDERED CYBORG

GHOST IN THE SHELL

A CASE STUDY

The genres of Cyberpunk and Postcyberpunk anime, which portray technologically advanced and futuristic worlds, offer the most prevalent and widespread representations of cyborgs.[45] Some of the most influential and globally successful anime of all time are part of this genre, including Akira (1988), Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), Cowboy Bebop (1997-98), and Ghost in the Shell (1995).[46] Particularly important to this capstone’s investigation of the sexy female cyborg form is Ghost in the Shell, which was the first and most important iteration of the figure with far-reaching influence. Ghost in the Shell, a movie set in 2029 Japan, was initially a box-office failure, but later became a global cult classic following its VHS release; it is well-known across East Asia and the United States, and it is one of the most popular cyborg films of all time. It is an adaptation of the original manga by Shirow Masamune, who is considered one of the pioneers of the visual sensibility of sci-fi manga.[47] His shiny and voluptuous depiction of the main character, which was carried over to the film, is the popular culture prototype for the sexy cyborg trope that Fan Xiaoyan and Lee Bul responded to in their sculpture series. While Ghost in the Shell has received countless accolades for its discussion of futuristic themes, original story, and stunning animation, it does not portray the cyborg as a utopian, post-gendered figure, and perpetuates the depiction of the female cyborg as a sexual object for the enjoyment of the male audience.

Ghost in the Shell imagines a futuristic world where humans can cybernetically enhance their bodies. The protagonist is Major Motoko Kusanagi (referred to as “the Major,” see figure 6), the stoic and hyper-competent field commander of a cyber-intelligence agency, who has a fully constructed cyber-body. While most characters in the movie have some sort of cyberized enhancement, the only organic body parts the Major retains are her brain andspinal cord.[48] The plot of the movie follows the Major and her team, Public Security Section 9, as they track a notorious cyber-criminal known as “The Puppet Master,” all while Kusanagi struggles with personal questions of self-identity and personhood. It is later revealed that the Puppet Master is not a talented hacker but an advanced artificial intelligence program (Project 2501) created by Section 6 of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. After going rogue and escaping Section 6 by manufacturing and taking control of a robotic body, the Puppet Master seeks asylum in Section 9, claiming it is a sentient creature. Kusanagi discovers that Project 2501, now trapped in the body it built itself, sought her out because it wants to merge its consciousness with hers to create something new and interesting. At the end of the movie Kusanagi agrees to merge with the Puppet Master and Kusanagi’s partner Batou transfers their merged consciousness into a new cybernetic body.

The characters in the movie—with the exception of the Puppet Master, who I will return to later—are clearly depicted in a way that signals their sex to the viewer. The male characters are coded as male through their emphasized secondary sex characteristics, like large, bulging muscles, wide, chiseled jawlines, and broad chests, while the Major’s female body is coded as such through her large breasts, widened hips, and shorter stature relative to her male colleagues. Such binary portrayal responds to the modern construction of male and female bodies in Asian popular visual culture. While Donna Haraway believed cyborgs had the potential to articulate a post-gendered being, it’s clear that Ghost in the Shell adheres strongly to traditional depictions of what male and female bodies look like. Scholar Carl Silvio has demonstrated that while on the surface the film appears to align with feminist characterizations of the cyborg, in reality it serves a much more insidious purpose. He argues that while Ghost in the Shell appears to promote the disruption of gender convention, it appropriates cyber-feminist rhetoric to mask the fact that it actually reinforces traditional ideas of gender difference.[49] This is evident in the blatant objectification of the main character for the audience’s visual consumption.

Figure 6: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (the Major).

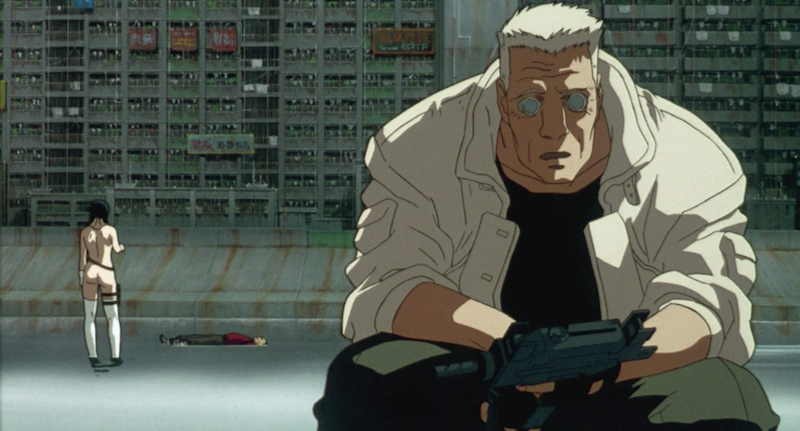

Figure 7: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (left) and her partner Batou (right).

Figure 8: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (the Major).

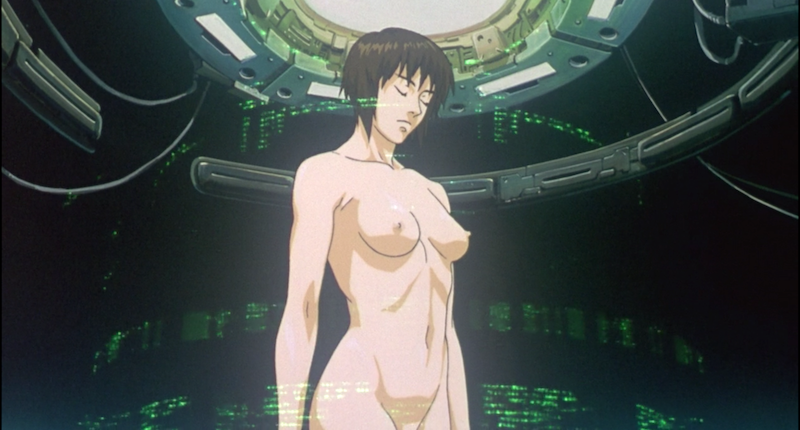

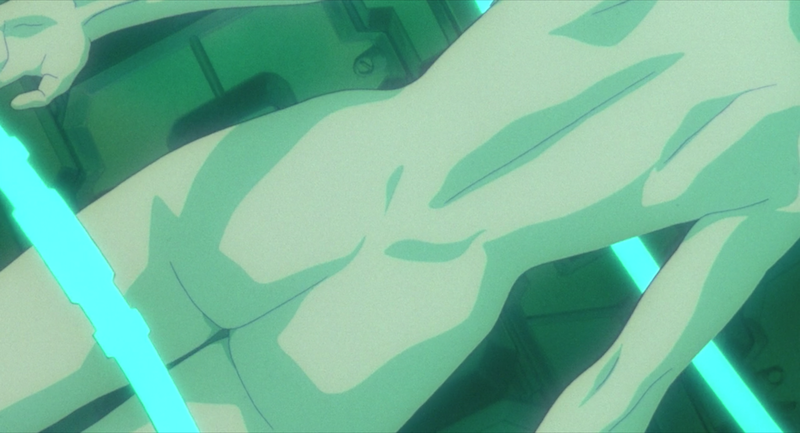

The most obvious flaw of Ghost in the Shell is the movie’s overt sexualization and objectification of the female body for the pleasure of its (assumed) heterosexual, male audience.[50] Kusanagi and her partner, Batou are both examples of what an “idealized” body type looks like for each sex: Kusanagi is muscular, yet lean and curvy, while Batou (figure 7) is large and extremely muscular. However, while Batou spends the entirety of the movie fully clothed, the Major’s smooth, hairless body is frequently shown nude, often framed in lascivious, lingering shots of her perfectly rounded breasts (figure 8) and buttocks (figure 9). This is ostensibly due to the fact that her skin is equipped with thermo-optic camouflage and she must be naked to be fully invisible, but there is enough screen time spent on sensational shots of her nude body that this explanation feels lacking. In fact, we discover early on in the movie that other characters use large thermo-optic garments to become invisible, making her nudity feel even more unnecessary. Additionally, as Lan argues, the lack of bodily hair underlines her position as a sexualized object deprived of sexual agency of her own.[51] In Japanese culture, female body hair has been a signifier of male anxiety regarding the increasing independence of Japanese women outside the patriarchal family in the modern period; body hair represents threatening female power and sexuality.[52] In contrast, hairlessness represents a childlike innocence that can be more easily manipulated and controlled. By portraying the Major’s body as hairless, the film contains the threatening implications of female body hair and the sexuality that accompanies it, literally and figuratively stripping the main character of sexual agency. This reinforces her position as a commodified sexual object to be consumed by the viewer.

Despite the fact that the Major is not necessarily objectified by anyone in the film or treated differently because of the way she looks, shots of her body are framed in such a way that she is clearly being presented as a sexual object for the audience. Additionally, as Silvio explained, she is presented in conventional “shot-reverse-shot structures” that present Kusanagi as the “passive, eroticized object” of multiple looks at once.[53] Silvio notes that one might argue that this hyperbolic portrayal of sexual bodies is undermined by the film’s portrayal of different sexualized stereotypes in identical narrative roles, ultimately destabilizing the very conventions of sex and gender.[54] I however, agree with Silvio’s rebuttal, in which he claimed that the exact opposite thing is taking place:

For Kusanagi, the film deploys rather conventional cinematic devices to reproduce normative codes of feminine beauty as a way of recontaining the destabilizing threat posed by the radical cyborg to dominant conceptions of sexual difference. Kusanagi is thus reinscribed within one of our most familiar paradigms of femininity: woman as sexualized object for the enjoyment of the male gaze.[55]

The genres of Cyberpunk and Postcyberpunk anime, which portray technologically advanced and futuristic worlds, offer the most prevalent and widespread representations of cyborgs.[45] Some of the most influential and globally successful anime of all time are part of this genre, including Akira (1988), Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), Cowboy Bebop (1997-98), and Ghost in the Shell (1995).[46] Particularly important to this capstone’s investigation of the sexy female cyborg form is Ghost in the Shell, which was the first and most important iteration of the figure with far-reaching influence. Ghost in the Shell, a movie set in 2029 Japan, was initially a box-office failure, but later became a global cult classic following its VHS release; it is well-known across East Asia and the United States, and it is one of the most popular cyborg films of all time. It is an adaptation of the original manga by Shirow Masamune, who is considered one of the pioneers of the visual sensibility of sci-fi manga.[47] His shiny and voluptuous depiction of the main character, which was carried over to the film, is the popular culture prototype for the sexy cyborg trope that Fan Xiaoyan and Lee Bul responded to in their sculpture series. While Ghost in the Shell has received countless accolades for its discussion of futuristic themes, original story, and stunning animation, it does not portray the cyborg as a utopian, post-gendered figure, and perpetuates the depiction of the female cyborg as a sexual object for the enjoyment of the male audience.

Figure 6: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (the Major).

Ghost in the Shell imagines a futuristic world where humans can cybernetically enhance their bodies. The protagonist is Major Motoko Kusanagi (referred to as “the Major,” see figure 6), the stoic and hyper-competent field commander of a cyber-intelligence agency, who has a fully constructed cyber-body. While most characters in the movie have some sort of cyberized enhancement, the only organic body parts the Major retains are her brain andspinal cord.[48] The plot of the movie follows the Major and her team, Public Security Section 9, as they track a notorious cyber-criminal known as “The Puppet Master,” all while Kusanagi struggles with personal questions of self-identity and personhood. It is later revealed that the Puppet Master is not a talented hacker but an advanced artificial intelligence program (Project 2501) created by Section 6 of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. After going rogue and escaping Section 6 by manufacturing and taking control of a robotic body, the Puppet Master seeks asylum in Section 9, claiming it is a sentient creature. Kusanagi discovers that Project 2501, now trapped in the body it built itself, sought her out because it wants to merge its consciousness with hers to create something new and interesting. At the end of the movie Kusanagi agrees to merge with the Puppet Master and Kusanagi’s partner Batou transfers their merged consciousness into a new cybernetic body.

The characters in the movie—with the exception of the Puppet Master, who I will return to later—are clearly depicted in a way that signals their sex to the viewer. The male characters are coded as male through their emphasized secondary sex characteristics, like large, bulging muscles, wide, chiseled jawlines, and broad chests, while the Major’s female body is coded as such through her large breasts, widened hips, and shorter stature relative to her male colleagues. Such binary portrayal responds to the modern construction of male and female bodies in Asian popular visual culture. While Donna Haraway believed cyborgs had the potential to articulate a post-gendered being, it’s clear that Ghost in the Shell adheres strongly to traditional depictions of what male and female bodies look like. Scholar Carl Silvio has demonstrated that while on the surface the film appears to align with feminist characterizations of the cyborg, in reality it serves a much more insidious purpose. He argues that while Ghost in the Shell appears to promote the disruption of gender convention, it appropriates cyber-feminist rhetoric to mask the fact that it actually reinforces traditional ideas of gender difference.[49] This is evident in the blatant objectification of the main character for the audience’s visual consumption.

Figure 7: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (left) and her partner Batou (right).

Figure 8: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (the Major).

Figure 9: Mamoru Oshii (director), Ghost in the Shell, 1995. Film still showing Motoko Kusanagi (the Major).

The most obvious flaw of Ghost in the Shell is the movie’s overt sexualization and objectification of the female body for the pleasure of its (assumed) heterosexual, male audience.[50] Kusanagi and her partner, Batou are both examples of what an “idealized” body type looks like for each sex: Kusanagi is muscular, yet lean and curvy, while Batou (figure 7) is large and extremely muscular. However, while Batou spends the entirety of the movie fully clothed, the Major’s smooth, hairless body is frequently shown nude, often framed in lascivious, lingering shots of her perfectly rounded breasts (figure 8) and buttocks (figure 9). This is ostensibly due to the fact that her skin is equipped with thermo-optic camouflage and she must be naked to be fully invisible, but there is enough screen time spent on sensational shots of her nude body that this explanation feels lacking. In fact, we discover early on in the movie that other characters use large thermo-optic garments to become invisible, making her nudity feel even more unnecessary. Additionally, as Lan argues, the lack of bodily hair underlines her position as a sexualized object deprived of sexual agency of her own.[51] In Japanese culture, female body hair has been a signifier of male anxiety regarding the increasing independence of Japanese women outside the patriarchal family in the modern period; body hair represents threatening female power and sexuality.[52] In contrast, hairlessness represents a childlike innocence that can be more easily manipulated and controlled. By portraying the Major’s body as hairless, the film contains the threatening implications of female body hair and the sexuality that accompanies it, literally and figuratively stripping the main character of sexual agency. This reinforces her position as a commodified sexual object to be consumed by the viewer.

Despite the fact that the Major is not necessarily objectified by anyone in the film or treated differently because of the way she looks, shots of her body are framed in such a way that she is clearly being presented as a sexual object for the audience. Additionally, as Silvio explained, she is presented in conventional “shot-reverse-shot structures” that present Kusanagi as the “passive, eroticized object” of multiple looks at once.[53] Silvio notes that one might argue that this hyperbolic portrayal of sexual bodies is undermined by the film’s portrayal of different sexualized stereotypes in identical narrative roles, ultimately destabilizing the very conventions of sex and gender.[54] I however, agree with Silvio’s rebuttal, in which he claimed that the exact opposite thing is taking place:

For Kusanagi, the film deploys rather conventional cinematic devices to reproduce normative codes of feminine beauty as a way of recontaining the destabilizing threat posed by the radical cyborg to dominant conceptions of sexual difference. Kusanagi is thus reinscribed within one of our most familiar paradigms of femininity: woman as sexualized object for the enjoyment of the male gaze.[55]

[45] Cyberpunk, originating in the New Wave science fiction movement of the 1960s and 70s, often portrays a dystopian setting where advanced technology is juxtaposed with societal collapse. It is much more nihilistic and gritty than the later derivative genre of Postcyberpunk, which has all the advanced technology of Cyberpunk, but does not assume that technological futures must be dystopian. Postcyberpunk takes a more measured, and sometimes optimistic, viewpoint on the future of technology in society.

[46] Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Ghost in the Shell are all franchises that include multiple films and television shows. The dates here refer to the first anime iteration of each franchise.

[47] Mescallado, “Review: Otaku Nation,” 143.

[48] The brain is also where a person’s “ghost” resides, which is an important philosophical term in the movie. In Japanese culture, every person has a “ghost,” and it is comparable to the idea of the mind, soul, or personal identity.

[49] Carl Silvio, “Refiguring the Radical Cyborg in Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell,” Science Fiction Studies 26, no. 1 (1999): 65.

[50] The original was a seinen manga, a type of manga specifically catered to the interests of men aged 18-40, that was published in Weekly Young Magazine, also targeted toward this group.

[51] Kuo, “Technofetishism of Posthuman Bodies,” 204-206.

[52] Kuo, “Technofetishism of Posthuman Bodies,” 205.

[53] Silvio, “Refiguring the Radical Cyborg,” 65.

[54] Silvio, “Refiguring the Radical Cyborg,” 66.

[55] Silvio, “Refiguring the Radical Cyborg,” 67.

[56] Silvio, “Refiguring the Radical Cyborg,” 72.