PART III | BUL IN A CHINA SHOP: LEE BUL’S PARADOXICAL CYBORGS

TRANSITION TO CYBORGS

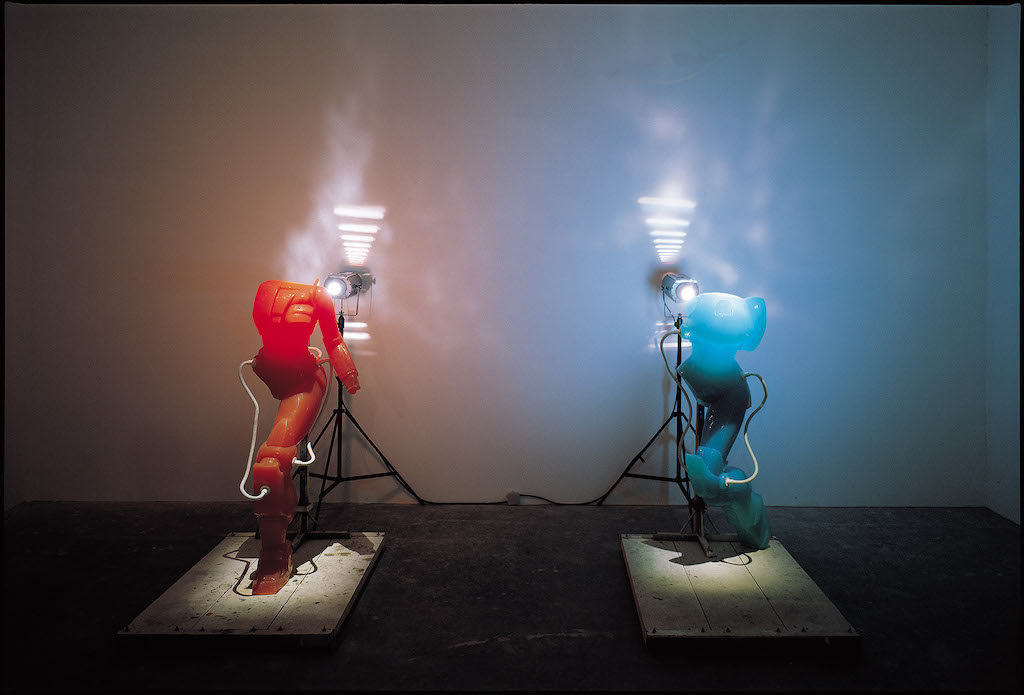

Lee’s first experiments in cyborg representation before her main series were Cyborg Red and Cyborg Blue (1997-98, figure 24-25), two installation sculptures made of cast silicone. They are truncated, abstracted, and mechanized versions of organic human bodies that are propped up by steel supports and sprout plastic tubing from within their bodies. Cyborg Red and Blue differ from her following series in two important ways: color and presentation. Though they are composed of cast silicone like Cyborg W1-W4 of her following series, they are colored a bold red and light blue, and appear semi-translucent because of the spotlights behind them. This translucency gives a visual sense that they are light or insubstantial, as well as non-human. Secondly, while the works in the following series are all hung, liberated from their pedestals, these two are thoroughly grounded. Each sculpture rests one foot on the worn, well-used wood platforms, and the black metal supports further anchor them to the ground, giving a sense of solidity or groundedness. The two elements of insubstantiality and groundedness create a visual ambiguity that is similar to that present in the Cyborg W1-W10. Lastly, these figures, like her following series, are coded female and sexualized through their hourglass body shape and an emphasis on their breasts, hips, and waists. These features qualify them as the prototypes for her second series, which is a more fully realized articulation of her conception of the cyborg.

Cyborg Red and Blue were followed by Lee’s long-running series Cyborg W1-W10 (1998-2006, figure 26-35). These sculptures are white, displayed hanging from the ceiling on wire, and show a considerable evolution in style and material over time. Installation photos reveal that the sculptures in the series are sometimes hung above eye level in galleries which have higher ceilings (figure 30-31), so the average viewer must look up, or even crane their neck, to look at them. Most are six feet tall or larger, despite their lack of heads, making them larger than life sized. Lee Bul has stated that a visual inspiration for these works was the depiction of the idealized female body in Western culture:

“The white color, which is quite neutral and in a way ‘timeless,’ was primarily a means to engage with notions of classical sculpture while producing forms that would produce a complex interplay with this color. And another reason was to invoke mythical archetypes of heroism, of associating the color white with virtues.”[100]

She looked to Ancient Greek statues like the Venus de Milo (figure 36), which have historically been held up as representations of “ideal beauty” in European culture, for inspiration. Cyborg W9 (figure 34) evokes the Venus de Milo through the pure white color and suggestion of a contrapposto pose. Even the missing limbs themselves recall the Venus de Milo and other Classical sculptures that have been damaged over their thousands of years of existence, evoking the passage of time. However, the fragmented and distorted nature of the cyborg bodies disrupts a reading of the sculptures as a simple evocation of Classical beauty, leading scholars like H.G. Masters to describe this allusion as “ironic.”[101] There is something darker in these headless, hanging, and fragmented figures than a simple allusion to Western sculpture.[102]

Figure 24: Lee Bul, Cyborg Red & Cyborg Blue, 1997-98. Cast silicone, paint pigment, steel pipe support and base, 160 x 70 x 110 cm each. Installation view of Le Consortium centre d’art contemporain, Dijon, 2002. Photo: André Morin. Photo Courtesy: Le Consortium.

Figure 25: Left: Lee Bul, Cyborg Red, 1997-98. Cast silicone, paint pigment, steel pipe support and base, 160 x 70 x 110 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist. Right: Lee Bul, Cyborg Blue, 1997-98. Cast silicone, paint pigment, steel pipe support and base, 160 x 70 x 110 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 20: Lee Bul, Cyborg W1-W4, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Lee’s first experiments in cyborg representation before her main series were Cyborg Red and Cyborg Blue (1997-98, figure 24-25), two installation sculptures made of cast silicone. They are truncated, abstracted, and mechanized versions of organic human bodies that are propped up by steel supports and sprout plastic tubing from within their bodies. Cyborg Red and Blue differ from her following series in two important ways: color and presentation. Though they are composed of cast silicone like Cyborg W1-W4 of her following series, they are colored a bold red and light blue, and appear semi-translucent because of the spotlights behind them. This translucency gives a visual sense that they are light or insubstantial, as well as non-human. Secondly, while the works in the following series are all hung, liberated from their pedestals, these two are thoroughly grounded. Each sculpture rests one foot on the worn, well-used wood platforms, and the black metal supports further anchor them to the ground, giving a sense of solidity or groundedness. The two elements of insubstantiality and groundedness create a visual ambiguity that is similar to that present in the Cyborg W1-W10. Lastly, these figures, like her following series, are coded female and sexualized through their hourglass body shape and an emphasis on their breasts, hips, and waists. These features qualify them as the prototypes for her second series, which is a more fully realized articulation of her conception of the cyborg.

Figure 24: Lee Bul, Cyborg Red & Cyborg Blue, 1997-98. Cast silicone, paint pigment, steel pipe support and base, 160 x 70 x 110 cm each. Installation view of Le Consortium centre d’art contemporain, Dijon, 2002. Photo: André Morin. Photo Courtesy: Le Consortium.

Figure 25: Left: Lee Bul, Cyborg Red, 1997-98. Cast silicone, paint pigment, steel pipe support and base, 160 x 70 x 110 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist. Right: Lee Bul, Cyborg Blue, 1997-98. Cast silicone, paint pigment, steel pipe support and base, 160 x 70 x 110 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Cyborg Red and Blue were followed by Lee’s long-running series Cyborg W1-W10 (1998-2006, figure 26-35). These sculptures are white, displayed hanging from the ceiling on wire, and show a considerable evolution in style and material over time. Installation photos reveal that the sculptures in the series are sometimes hung above eye level in galleries which have higher ceilings (figure 30-31), so the average viewer must look up, or even crane their neck, to look at them. Most are six feet tall or larger, despite their lack of heads, making them larger than life sized. Lee Bul has stated that a visual inspiration for these works was the depiction of the idealized female body in Western culture:

“The white color, which is quite neutral and in a way ‘timeless,’ was primarily a means to engage with notions of classical sculpture while producing forms that would produce a complex interplay with this color. And another reason was to invoke mythical archetypes of heroism, of associating the color white with virtues.”[100]

Figure 20: Lee Bul, Cyborg W1-W4, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

She looked to Ancient Greek statues like the Venus de Milo (figure 36), which have historically been held up as representations of “ideal beauty” in European culture, for inspiration. Cyborg W9 (figure 34) evokes the Venus de Milo through the pure white color and suggestion of a contrapposto pose. Even the missing limbs themselves recall the Venus de Milo and other Classical sculptures that have been damaged over their thousands of years of existence, evoking the passage of time. However, the fragmented and distorted nature of the cyborg bodies disrupts a reading of the sculptures as a simple evocation of Classical beauty, leading scholars like H.G. Masters to describe this allusion as “ironic.”[101] There is something darker in these headless, hanging, and fragmented figures than a simple allusion to Western sculpture.[102]

Figure 26: Lee Bul, Cyborg W1, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment, 185 x 56 x 58 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 27: Lee Bul, Cyborg W2, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment, 185 x 56 x 58 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 28: Lee Bul, Cyborg W3, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment, 185 x 81 x 58 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

The first four iterations (figure 26-29), completed in 1998, are made of cast silicone, a material that is known for its compatibility with the human body, and several scholars have argued its use may refer to plastic surgery.[103] Cyborg W1-W4 are executed in a retrofuturistic style that features elaborate and overlapping geometric forms and allusions to the aesthetics of past technology.[104] The forms of these four sculptures are blocky and exaggerated, especially their idealized female traits (breasts, large hips, and thin waists). Each sculpture is missing a head, one arm, and one leg, and they are always displayed hanging on wire, either from a built structure or the ceiling.

Figure 30: Lee Bul, Cyborg W5, 1999. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, urethane coating, 150 x 55 x 90 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 31: Lee Bul, Cyborg W6, 2001. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 232 x 67 x 67 cm. Photo: Kim Hyun-soo. Photo Courtesy: Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

Cyborg W5-W7 (figure 30-32) mark her transition to a different medium, in which Lee hand-cut and attached separate ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) panels to a fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP) form. These cyborgs are even more ornamented than the first four in the series, and have a more layered appearance due to the change in material. For example, Cyborg W5 (figure 30) has tubes that sprout from the chest area and arm, overlapping planes of material on the chest, and flat, disc-like, sequential protrusions that emerge from the left hip. A layered, tube-like appendage that resembles vertebrae comes out of the left shoulder and connects to the lower back, perhaps standing in for the missing left arm. This style is visually crowded and looks more dramatic than the first four, especially under bright lighting. This is due to the change in process, which involves more overlapping forms that create depth and cast dramatic shadows on the sculptures’ surfaces. Again, each figure is headless and missing at least two limbs, and has recognizably female features, though they are less hyperbolic than in Cyborg W1-W4.

Figure 33: Lee Bul, Cyborg W8, 2004. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 181 x 65 x 115 cm. Photo: Atsushi Nakamichi/Nacása & Partners. Photo Courtesy: 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

Figure 34: Lee Bul, Cyborg W9, 2006. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 180 x 60 x 70 cm.

The last three, Cyborg W8-W10 (figure 33-35), were made using the same materials and process as the previous three, but indicate a shift to a style that differs starkly from the previous seven. This style might be considered more “futuristic” looking, due to its sleek, minimalistic aesthetic.[105] The forms are simpler and more streamlined, and the body looks as if it is deliberately armored. The armor is close-fit to the body, similar to clothing or armor in some Cyberpunk anime (figure 37) and modern movies (figure 38). In other contexts where armor like this appears, like in anime and action movies, it is not simply decorative, and its use is linked to the dangerous, action-packed, and violent scenarios the characters encounter. Indeed, cyborg technology more generally is inherently linked to militarism and violence; many cybernetic enhancements like prosthetic arms and legs only exist as a result of military research and development.[106] The more realistic armor and bodies of these sculptures, especially Cyborg W9 and W10, link them visually to this real-world connection between modern militarism and cyborg technology. Despite the more simplified style, the female body continues to be invoked in through the emphasis on breasts and hips, as well as through references to clothing. In Cyborg W9 and W10, each sculpture has an attachment or apparel that resembles underwear, which is clear when seen from the back (figure 39). The combination of the sexy female body and revealing underwear indicates an association with the commodified female form, which is often presented with little to no clothing in advertisements and media.

Lee Bul has cited several diverse influences for these sculptures, including classical sculpture (figure 36) and anime. Her citation of these influences has shaped the writing about her work to some extent, but many writers also invoke Haraway’s cyborg theory in order to discuss Cyborg W1-W10. However, whether scholars invoke theory or anime in their interpretations, they neglect specific visual analysis in their work, and none to my knowledge have surveyed the entire series. I fill this gap by synthesizing the ideas of cyborg theory as well as representations of the cyborg in anime and attending more specifically to the visual elements of the sculptures. Overall, the scholarship falls into two camps: those who have argued that her series represents more postmodern, universal human concerns, and those who took a socio-historical, identity-based, or feminist approach. Those in the first camp often focused on the series’ connection to cyborg theory and postmodern theory. Some posited that the sculptures comment on the eternal human desire for bodily perfection,[107] while some saw the series as an expression of the postmodern consciousness, which is characterized as fragmented, unstable, and ever-changing. Here the sculptures’ visual form, fragmented, distorted, and ambiguous, has been described as a concrete articulation of the postmodern era. Rebecca Gordon Nesbitt, for example, believed the cyborgs represent a more general crisis of the human body in the contemporary period, in which the body is simply seen as a shell for the mind.[108] Lee Bul herself has admitted to knowledge of Haraway’s theories, but did not originally have them in mind when she created her series.[109] Despite this, many scholars have continued to use cyborg theory as an analytical framework due to the preeminence and staying power of Haraway’s work in cyborg discourse. However, these writers neglect the connection with anime, which is critical to interpreting her work.

Scholars in the second camp, who have discussed both cyborg theory and anime, usually argued that the sculptures offer commentary on gender (or less frequently, race). Rhee Jieun, for example, used Haraway’s theory of “woman of color” as a quintessential cyborg identity to discuss how Lee’s cyborg sculptures disrupt and disassemble stereotypes surrounding Asian women.[110] Others discussing gendered issues considered on the sculptures’ relationship with anime representations of cyborgs, which are often problematically sexualized. Roman Kurzmeyer, who characterizes Lee’s cyborg sculptures as a “classic male fantasy” that are at once threatening and submissive, attributes these qualities to representations of female cyborgs in anime, who are physically powerful, yet always given distinctively feminine or “girlish” features.[111] He correctly points out that this reference to futuristic anime makes it clear that despite technological advancement in these narratives, traditional gender norms have persisted.[112] However, these identity based approaches often lack the nuance to deal with the numerous ambiguities present in the sculpture series, and do not present visual evidence for their conclusions. In what follows, I examine how the sculptures embody some aspects of cyborg theory through ambiguity. However, though the framework of cyborg theory does allow for an analysis of some of the series’ key attributes, its utopian premise occludes a more detailed and nuanced examination.

Figure 36 (left): Alexandros of Antioch, Venus de Milo, 150-125 BCE. Parian Marble, 204 cm.

Figure 37 (center): Poster for cyberpunk anime miniseries “Bubblegum Crisis” (1987-1991), 1987.

Figure 38 (right): Poster for Black Widow (2021), 2020.

Figure 39: Lee Bul, Cyborg W9 (back view), 2006 with Cyborg W10 (2006), Chiasma (2005) and Untitled (Anagram drawings No.2-5) in the background. Installation view of Domus Artium 02, Salamanca, 2007. Photo: Santiago Santos. Photo Courtesy: Domus Artium 02, Salamanca.

Figure 36 (left): Alexandros of Antioch, Venus de Milo, 150-125 BCE. Parian Marble, 204 cm.

Figure 37 (center): Poster for cyberpunk anime miniseries “Bubblegum Crisis” (1987-1991), 1987.

Figure 38 (right): Poster for Black Widow (2021), 2020.

Figure 39: Lee Bul, Cyborg W9 (back view), 2006 with Cyborg W10 (2006), Chiasma (2005) and Untitled (Anagram drawings No.2-5) in the background. Installation view of Domus Artium 02, Salamanca, 2007. Photo: Santiago Santos. Photo Courtesy: Domus Artium 02, Salamanca.

Lee Bul has cited several diverse influences for these sculptures, including classical sculpture (figure 36) and anime. Her citation of these influences has shaped the writing about her work to some extent, but many writers also invoke Haraway’s cyborg theory in order to discuss Cyborg W1-W10. However, whether scholars invoke theory or anime in their interpretations, they neglect specific visual analysis in their work, and none to my knowledge have surveyed the entire series. I fill this gap by synthesizing the ideas of cyborg theory as well as representations of the cyborg in anime and attending more specifically to the visual elements of the sculptures. Overall, the scholarship falls into two camps: those who have argued that her series represents more postmodern, universal human concerns, and those who took a socio-historical, identity-based, or feminist approach. Those in the first camp often focused on the series’ connection to cyborg theory and postmodern theory. Some posited that the sculptures comment on the eternal human desire for bodily perfection,[107] while some saw the series as an expression of the postmodern consciousness, which is characterized as fragmented, unstable, and ever-changing. Here the sculptures’ visual form, fragmented, distorted, and ambiguous, has been described as a concrete articulation of the postmodern era. Rebecca Gordon Nesbitt, for example, believed the cyborgs represent a more general crisis of the human body in the contemporary period, in which the body is simply seen as a shell for the mind.[108] Lee Bul herself has admitted to knowledge of Haraway’s theories, but did not originally have them in mind when she created her series.[109] Despite this, many scholars have continued to use cyborg theory as an analytical framework due to the preeminence and staying power of Haraway’s work in cyborg discourse. However, these writers neglect the connection with anime, which is critical to interpreting her work.

Scholars in the second camp, who have discussed both cyborg theory and anime, usually argued that the sculptures offer commentary on gender (or less frequently, race). Rhee Jieun, for example, used Haraway’s theory of “woman of color” as a quintessential cyborg identity to discuss how Lee’s cyborg sculptures disrupt and disassemble stereotypes surrounding Asian women.[110] Others discussing gendered issues considered on the sculptures’ relationship with anime representations of cyborgs, which are often problematically sexualized. Roman Kurzmeyer, who characterizes Lee’s cyborg sculptures as a “classic male fantasy” that are at once threatening and submissive, attributes these qualities to representations of female cyborgs in anime, who are physically powerful, yet always given distinctively feminine or “girlish” features.[111] He correctly points out that this reference to futuristic anime makes it clear that despite technological advancement in these narratives, traditional gender norms have persisted.[112] However, these identity based approaches often lack the nuance to deal with the numerous ambiguities present in the sculpture series, and do not present visual evidence for their conclusions. In what follows, I examine how the sculptures embody some aspects of cyborg theory through ambiguity. However, though the framework of cyborg theory does allow for an analysis of some of the series’ key attributes, its utopian premise occludes a more detailed and nuanced examination.

[100] Franck Gautherot, “Lee Bul: Supernova in Karaoke Land” [Interview with Lee Bul], Flash Art International, no.217 (March-April 2001): 83.

[101] H.G. Masters, “Wayward Tangents: Lee Bul,” ArtAsiaPacific 56 (Nov/Dec 2007): 128.

[102] While this capstone does not delve into the connection with Classical sculpture or theories of sculpture due to its focus on the treatment of the female body, these theoretical concerns pose interesting directions for future scholarship on Lee’s cyborg sculptures. For example, further research could consider how these “flying cyborgs” modify Rosalind Krauss’ ideas in Passages in Modern Sculpture and other theories regarding the location of sculpture (i.e., the move from the monument to the pedestal or from a grounded, sited location to something that is ungrounded). These works are are located overhead, activating and activated by the ceiling itself. This seems to advance yet another stage in the process of the relocation/dislocation of the place of sculpture. See Rosalind Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1981).

[103] Rhee Jieun relates this to the “plastic surgery boom” occurring in some East Asian countries and suggests that Lee’s use of the material could imply that her sculptures are an “objectification of desirable Western bodies as much as for a futuristic women-warrior.” See Rhee Jieun, “From Goddess to Cyborg: Mariko Mori and Lee Bul,” N. paradoxa 14 (July 2004): 10-11.

[104] This stylistic choice of single actual material in combination with hybrid material references, and the later change to a different material and process, raises several theoretical and practical lines of inquiry. However, more evidence is necessary to discern if Lee’s choices of medium were due to theoretical concerns or material choices and constraints.

[105] The distinctions between these two styles can be visualized in several movies, one of which is the Disney movie WALL-E (2008). It is similar to the distinction between WALL-E, the old-fashioned robot, and EVE, the new robot whose character design was done by Jonathan Ive, the designer of the iPod.

[106] Hamraie and Fritsch, “Crip Technoscience Manifesto,” 3.

[107] Kataoka, “In Pursuit of Something Between the Self and the Universe,” 32.

[108] Rebecca Gordon Nesbitt, “The Divine Shell: An Introduction to the Work of Lee Bul,” Lee Bul: The Divine Shell, exhibition catalogue (Wien: Bawag Foundation, February 16 – April 1, 2001), 9. Quoted in Cho, “Can the Subaltern Artist Speak?,” 164-65.

[109] Obrist, “Lee Bul,” 530.

[110] Rhee, “From Goddess to Cyborg,” 11-12.

[111] Roman Kurzmeyer, “Cyborgs” in Lee Bul: in Medias Res, trans. John Southard (Seoul: Ssamzie Art Project, 1999), 24.

[112] Hans Rudolf Reust, “Lee Bul in der Kunsthalle Bern im Projektraum,” cited in Kurzmeyer, “Cyborgs,” 24.