PART III | BUL IN A CHINA SHOP: LEE BUL’S PARADOXICAL CYBORGS

LEE BUL: RADICAL ARTIST

Lee Bul (figure 21), born in 1964 in Yeongweol, grew up during a harsh military dictatorship and the subsequent transition to republican democracy. Because her parents were left-wing political dissidents under dictator Park Chung-hee’s rule, they had to move frequently to avoid political persecution.[87] These childhood experiences were formative for Lee’s mindset and artistic practice, which she felt was the only way she could express herself in a politically repressive environment.[88] Of these experiences, she stated that they

taught me certain strategies of survival. I learned that you can’t be a revolutionary and hope to survive, but that you can remain elusive, iconoclastic, alert to the fissures that you can penetrate in order to destabilize a rigid, oppressive system. On the other hand, I don’t think it made my art politically conscious in any overt way.[89]

This statement in many ways characterizes Lee’s artistic practice, which is politically and socially conscious, yet ambiguous and suggestive, rather than straightforward. Upon graduating from Hongik University in 1987, the same year that South Korea declared itself a representative democracy, Lee began exhibiting her early performance work to ambivalent reviews. At the time, the South Korean art scene was dominated by two main art movements: modernist Monochrome painting (tansaekhwa) and “People’s Art” (Minjung misul). Monochrome painting, which originated in the 1960s and came from the fusion of Western minimalism and Taoist philosophy, maintained a privileged status in the South Korean art world in the 1970s and 80s.[90] The People’s Art movement, similar to Chinese Socialist Realism, was based in social and political activism and arose in challenge to Monochrome painting’s dominance. Members of the People’s Art movement criticized modernist artists for their reliance on Western art forms and advocated for art that reflected a “national culture.”[91]

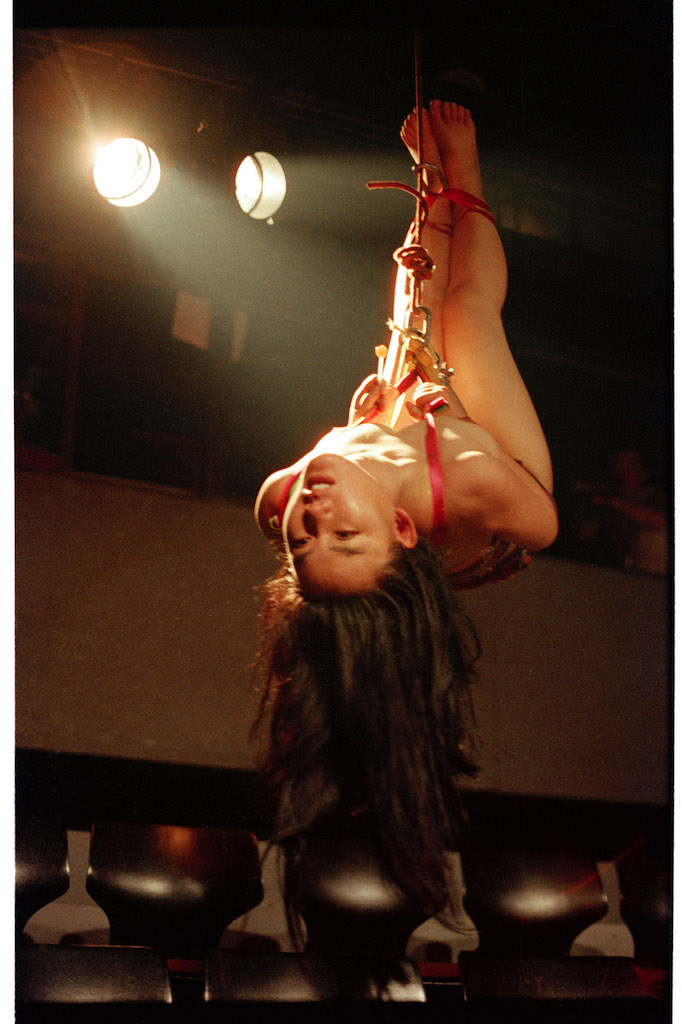

In sum, when Lee graduated in 1987, the South Korean art world was divided between two movements that were diametrically opposed in both ideology and style. Because of her upbringing and resistance to “totalizing ideas and claims to absolutes—aesthetic or otherwise,” Lee did not feel an affinity for either of these movements.[92] She specifically felt that the Minjung misul movement, which claimed to be the people’s “art of liberation,” was “naive and even fraudulent, this notion that you could confront guns and nightsticks with paintbrushes and canvases.”[93] Performance art was, then, an oppositional artistic strategy for Lee as she found her artistic voice outside of these two dominant discourses. At the time, performance art was still considered to be radical and relatively marginal, and her work initially received mixed reviews. Her early performances, which include Abortion in 1989 (figure 22) and Sorry for suffering—You think I’m a puppy on a picnic? in 1990 (figure 23) were characterized by a focus on the body and her personal experiences, as well as allegorical political references. For example, Abortion involved a nude Lee hanging upside down (a precursor to the display of her hanging cyborg series) while she discussed her experience of an abortion. This performance, like her other early work, was a deeply personal expression of her own life that also attempted to reach out to others with the same experiences. But as discourses about feminism and body politics became more widespread in the 1990s in Korea, people began to read political and social themes into her work—whether it was her original intention or not.[94] Lee attributed the critical reinterpretation of her work in the context of feminism to her identity as a woman, stating,

I’m not so sure, though, that I had a definite activist agenda in mind when I began these performances… But the fact that I was a woman doing this in public gave it a political dimension. And that I was dealing with aspects of the body, my body—which, of course, happens to be feminine—made it controversial, and even confrontational, for many people.[95]

This does not mean that her works have no political implications; rather, it is a representation of the artist’s resistance to being categorized, especially because of her gender. Despite the fact that she “probably could be called a feminist until the first part of the 1990s,” Lee stated in a 2002 interview that, “I would say I’m not now because that word rules out lots of other concepts.”[96] The artist has often been quoted as denying the term “feminist” in relation to her work, and Hyeok Cho attributes this to the limitations of feminist discourse and Lee Bul’s greater project of creating ambiguity and blurring boundaries. According to Cho, her rejection of the feminist label comes out of a desire to think about difference in ways that do not refer to “reductive and totalizing systems of thought” and open up new possibilities for examining her specific experience as a woman artist.[97]

This is consistent with many other East Asian woman artists of Lee Bul’s generation, who express discomfort with the feminist label and an emphasis on female identity. Paek Chi-suk, the director of the 1999 exhibition “Women’s Art Festival 99: The March of Patzzis” noted that many of the young artists included in the feminist festival (a group which included Lee) personally rejected the title of feminist.[98] She attributed this to the artists’ belief that categorization leads to stereotyping, which in turn prevented a deep and meaningful engagement with their work.[99] The artists believed that Paek limited the interpretation of their art within a feminist or female-centered framework by categorizing their work as feminist. The curator’s impression of this trend is consistent with Lee’s 2002 statement that identification with the term feminist “rules out lots of other concepts.” This is a useful framework to keep in mind when analyzing Lee’s cyborg sculptures, which deal with matters of gendered representation but should not be considered wholly within the realm of “feminist art.” This framework allows for an interpretation of Lee Bul’s work that does not rely on it conveying a “feminist” message and can consider the ways in which the sculptures might validate, rather than reject, the male gaze.

Figure 21: Lee Bul. Courtesy of Swarovski Kristallwelten and Lehmann Maupin, New York City, Hong Kong, and Seoul. Photo by Klaus Vyhnalek.

Figure 22: Lee Bul, Abortion, 1989. Performance, The 1st Korea–Japan Performance Festival, Lobby Theater, Dongsoong Art Center, Seoul. Courtesy of the artist.

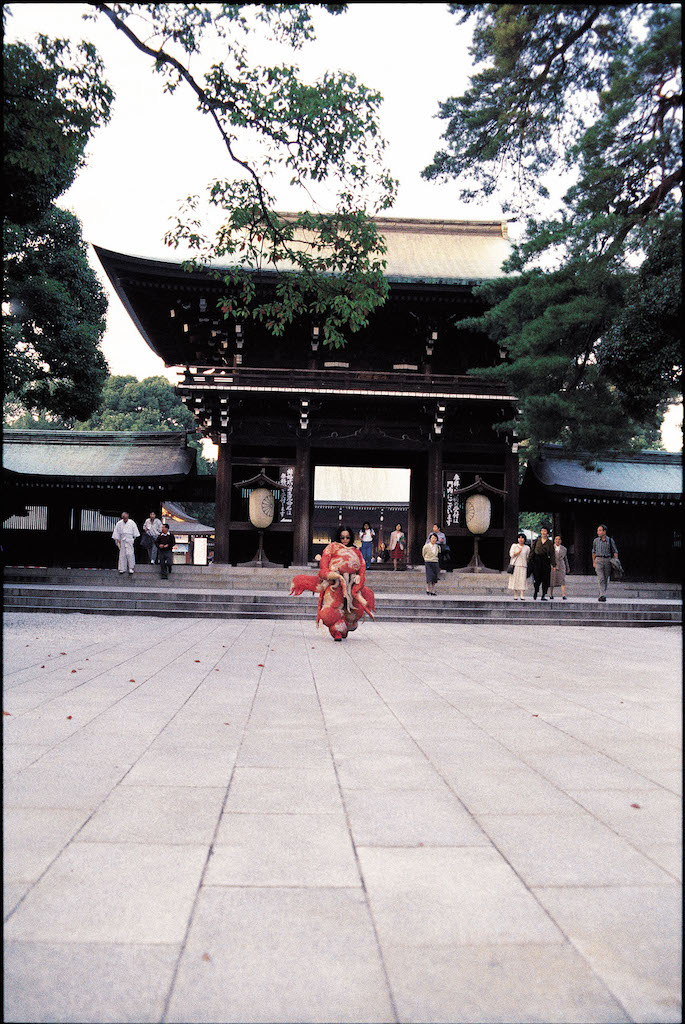

Figure 23: Lee Bul, Sorry for suffering–You think I’m a puppy on a picnic?, 1990. Performance, 12 days, The 2nd Japan and Korea Performance Festival, Gimpo Airport, Korea; Narita Airport, Meiji Shrine, Harajuku, Otemachi Station, Koganji Temple, Asakusa, Shibuya, University of Tokyo and Tokiwaza Theater, Tokyo, Japan. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 21: Lee Bul. Courtesy of Swarovski Kristallwelten and Lehmann Maupin, New York City, Hong Kong, and Seoul. Photo by Klaus Vyhnalek.

Lee Bul (figure 21), born in 1964 in Yeongweol, grew up during a harsh military dictatorship and the subsequent transition to republican democracy. Because her parents were left-wing political dissidents under dictator Park Chung-hee’s rule, they had to move frequently to avoid political persecution.[87] These childhood experiences were formative for Lee’s mindset and artistic practice, which she felt was the only way she could express herself in a politically repressive environment.[88] Of these experiences, she stated that they

taught me certain strategies of survival. I learned that you can’t be a revolutionary and hope to survive, but that you can remain elusive, iconoclastic, alert to the fissures that you can penetrate in order to destabilize a rigid, oppressive system. On the other hand, I don’t think it made my art politically conscious in any overt way.[89]

This statement in many ways characterizes Lee’s artistic practice, which is politically and socially conscious, yet ambiguous and suggestive, rather than straightforward. Upon graduating from Hongik University in 1987, the same year that South Korea declared itself a representative democracy, Lee began exhibiting her early performance work to ambivalent reviews. At the time, the South Korean art scene was dominated by two main art movements: modernist Monochrome painting (tansaekhwa) and “People’s Art” (Minjung misul). Monochrome painting, which originated in the 1960s and came from the fusion of Western minimalism and Taoist philosophy, maintained a privileged status in the South Korean art world in the 1970s and 80s.[90] The People’s Art movement, similar to Chinese Socialist Realism, was based in social and political activism and arose in challenge to Monochrome painting’s dominance. Members of the People’s Art movement criticized modernist artists for their reliance on Western art forms and advocated for art that reflected a “national culture.”[91]

Figure 22: Lee Bul, Abortion, 1989. Performance, The 1st Korea–Japan Performance Festival, Lobby Theater, Dongsoong Art Center, Seoul. Courtesy of the artist.

In sum, when Lee graduated in 1987, the South Korean art world was divided between two movements that were diametrically opposed in both ideology and style. Because of her upbringing and resistance to “totalizing ideas and claims to absolutes—aesthetic or otherwise,” Lee did not feel an affinity for either of these movements.[92] She specifically felt that the Minjung misul movement, which claimed to be the people’s “art of liberation,” was “naive and even fraudulent, this notion that you could confront guns and nightsticks with paintbrushes and canvases.”[93] Performance art was, then, an oppositional artistic strategy for Lee as she found her artistic voice outside of these two dominant discourses. At the time, performance art was still considered to be radical and relatively marginal, and her work initially received mixed reviews. Her early performances, which include Abortion in 1989 (figure 22) and Sorry for suffering—You think I’m a puppy on a picnic? in 1990 (figure 23) were characterized by a focus on the body and her personal experiences, as well as allegorical political references. For example, Abortion involved a nude Lee hanging upside down (a precursor to the display of her hanging cyborg series) while she discussed her experience of an abortion. This performance, like her other early work, was a deeply personal expression of her own life that also attempted to reach out to others with the same experiences. But as discourses about feminism and body politics became more widespread in the 1990s in Korea, people began to read political and social themes into her work—whether it was her original intention or not.[94] Lee attributed the critical reinterpretation of her work in the context of feminism to her identity as a woman, stating,

I’m not so sure, though, that I had a definite activist agenda in mind when I began these performances… But the fact that I was a woman doing this in public gave it a political dimension. And that I was dealing with aspects of the body, my body—which, of course, happens to be feminine—made it controversial, and even confrontational, for many people.[95]

This does not mean that her works have no political implications; rather, it is a representation of the artist’s resistance to being categorized, especially because of her gender. Despite the fact that she “probably could be called a feminist until the first part of the 1990s,” Lee stated in a 2002 interview that, “I would say I’m not now because that word rules out lots of other concepts.”[96] The artist has often been quoted as denying the term “feminist” in relation to her work, and Hyeok Cho attributes this to the limitations of feminist discourse and Lee Bul’s greater project of creating ambiguity and blurring boundaries. According to Cho, her rejection of the feminist label comes out of a desire to think about difference in ways that do not refer to “reductive and totalizing systems of thought” and open up new possibilities for examining her specific experience as a woman artist.[97]

Figure 23: Lee Bul, Sorry for suffering–You think I’m a puppy on a picnic?, 1990. Performance, 12 days, The 2nd Japan and Korea Performance Festival, Gimpo Airport, Korea; Narita Airport, Meiji Shrine, Harajuku, Otemachi Station, Koganji Temple, Asakusa, Shibuya, University of Tokyo and Tokiwaza Theater, Tokyo, Japan. Courtesy of the artist.

This is consistent with many other East Asian woman artists of Lee Bul’s generation, who express discomfort with the feminist label and an emphasis on female identity. Paek Chi-suk, the director of the 1999 exhibition “Women’s Art Festival 99: The March of Patzzis” noted that many of the young artists included in the feminist festival (a group which included Lee) personally rejected the title of feminist.[98] She attributed this to the artists’ belief that categorization leads to stereotyping, which in turn prevented a deep and meaningful engagement with their work.[99] The artists believed that Paek limited the interpretation of their art within a feminist or female-centered framework by categorizing their work as feminist. The curator’s impression of this trend is consistent with Lee’s 2002 statement that identification with the term feminist “rules out lots of other concepts.” This is a useful framework to keep in mind when analyzing Lee’s cyborg sculptures, which deal with matters of gendered representation but should not be considered wholly within the realm of “feminist art.” This framework allows for an interpretation of Lee Bul’s work that does not rely on it conveying a “feminist” message and can consider the ways in which the sculptures might validate, rather than reject, the male gaze.

[87] Kataoka Mami, “In Pursuit of Something Between the Self and the Universe,” in Lee Bul: From Me, Belongs to You Only, ed. Kataoka Mami (Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2012), 27.

[88] Kataoka, “In Pursuit of Something Between the Self and the Universe,” 27.

[89] Lee Bul, “Lee Bul: The Artist’s Two Bodies,” interview by Kim Seung-duk. Art Press, no. 279 (May 2002): 23.

[90] Hyeok Cho, “Can the Subaltern Artist Speak? Postmodernist Theory, Feminist Practice, and the Art of Lee Bul” (PhD dissertation, State University of New York at Binghamton, 2020), 37-38.

[91] Cho, “Can the Subaltern Artist Speak?,” 37-38.

[92] Lee, “Lee Bul: The Artist’s Two Bodies,” 23.

[93] Lee, “Lee Bul: The Artist’s Two Bodies,” 23.

[94] See Miriam Ching and Yoon Louie, “Minjung Feminism: Korean Women’s Movement for Gender and Class Liberation,” Women’s Studies International Forum 18, no. 4 (July 1, 1995): 417–30.

[95] Lee, “Lee Bul: The Artist’s Two Bodies,” 23.

[96] Kim Chŏng-hi, “Taejung munhwa wa ellit’ŭ tamnon sai ŭi honhyŏla [A Child of Mixed Blood between Pop Culture and Elite Discourses],” Wŏlgan misul [Monthly Art] 14, no. 2 (February 2002): 77, quoted in Cho, 90.

[97] Cho, “Can the Subaltern Artist Speak?,” 154.

[98] Paek Chi-suk, “99 yŏsŏng misulche ‘patzzi tŭl ŭi haengjin ŭl poksŭp hada [Reviewing “Women’s Art Festival 99: ‘The March of Patzzis’”],” Yŏsŏng kwa sahoe [Woman and Society] 11 (2000): 259, cited in Cho, 90-91.

[99] Paek, “Reviewing “‘Women’s Art Festival 99,’” 259, cited in Cho, 90-91.